[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he sharp reek of gunpowder – sulfur, charcoal and saltpeter – floods my nostrils the moment I step into the Los Angeles Gun Club, a 50-foot indoor shooting range in downtown L.A., with three friends. I twitch my nose and glance around, my heart banging with the irregular gunshots 30 feet away behind the soundproof glass windows.

The vestibule features safety instructions and colorful posters with autographs of celebrities including actor Ed Westwick and Tha Alkaholiks, an L.A. hip hop trio. A few more steps inside, facing two beige walls of firearm selections, we are overwhelmed by the deluge of new information.

“Chinese?” An employee, Charles Xu, comes by and asks in Mandarin. A 6 foot 3 thirtysomething, he has large hands and double chins.

We nod and ask for his recommendations. As Chinese students studying at the University of Southern California and gun novices, it’s our first time to touch real firearms. Xu spreads four clunky handguns across the table and asks us to try each of them.

I reach out for a pitch-black CZ P-01, my palms soaking the rubber grip with sweat. About 28 ounces, the handgun feels much chunkier than I expect. With a heavy first-round trigger pull, I’m told, any additional shots are a light, crisp single action. We decided to pick this one as a handgun and then a SIGM400 as a long gun.

Xu meanders through magazine, cartridge, slide and trigger, gushing safety instructions. Occasionally swallowed by gunshots, his Shanghai-style words hit us at a breakneck speed, which makes it hard for rookies to digest every step of a risky sport.

Finally we can put on the ear muffs and stride into the range behind the glass windows, where gunshots grow deafeningly louder and everyone shouts to communicate.

I stop at the sixth lane, load my CZ P-01, point the muzzle toward the target paper and pull the trigger. “Bang!” Gunpowder burns. Bullet flies away. Case spills behind. A thrill runs through my spine and I get a taste of breaking a taboo in my home country.

“Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” former Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong once remarked. Echoing his words, China banned private gun ownership across the nation in 1996, when Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Control of Firearms took effect. By law, no civilian may acquire, possess or transfer a firearm or ammunition.

Across the Pacific, however, as Chinese communities mushroom in California, more Chinese immigrants can be found in shooting ranges or have firearms at home for protection. This rising interest in the Second Amendment comes as hate crimes, assaults, and reports of harassment against the Asian American and Pacific Islander community are also increasing.

This coming Monday marks the one-year anniversary of the El Paso mass shooting. The hate crime is the largest anti-Latinx attack in U.S. history. It was reportedly fueled by xenophobic rhetoric coming from the White House, echoes of which can be heard or read in tweets about COVID-19.

After years of unmitigated mass shootings at schools, malls, concerts, theaters, festivals, any public space really, Americans remain divided over gun control measures. And yet, the firearm industry in California, the state with one of the nation’s toughest gun laws, is tailoring its services for Chinese by offering gun clubs, stores and training programs in their language with employees that look like them.

“There are mainly two types of Chinese customers,” Justin Zheng, an employee at a gun store Gun Effects, says. “The first [buy guns] for protection. The second are newcomers interested in guns but have no access in China.”

‘Pictures, Pictures, Pictures’

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]ith a history of over 30 years, the Los Angeles Gun Club is becoming increasingly popular among international customers. Accordingly, it offers free brief safety instructions in English, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Spanish.

“The demographic has changed,” says Ken Fukase, a Japanese-American employee with five years of working experience. The main customers are now Japanese, Chinese, and French.

But he notes that now still 30% of the customers are Chinese who abound in the club usually for one reason, “They’re not here to shoot. They’re here to take pictures. Pictures, pictures, pictures. Whenever we get mad at them, it’s usually because they wanna take pictures in a very dangerous way.”

Fukase recalls a Chinese father in his late 40s who asked his teenage daughter to take photos for him. The man pointed the gun straight into the camera which was in front of the girl’s face and everything’s loaded.

“At that moment, just this little part right here at your finger –” Fukase says as he points to the trigger of a virtual gun. “– and everything would have went bad. The dad could kill the daughter, maybe hurt some other people.”

In recent years, the employees tell Chinese customers specifically rules about pictures after knowing their No.1 priority, and find it acceptable as long as they obey the rules.

Ripple Effect

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]hile photo-lovers, mostly one-time tourists and F1-visa students, make up nearly 90% of Chinese customers, the other 10%, Fukase says, bring their own guns to the club for shooting. 2-5% of the gun owners are professionals, and Xu is also an expert.

“I hate it when people say they’re ‘playing’ guns,” says Xu. “Many of them come here and think it’s a game. How do you ‘play’ guns? These are not toys; they’re firearms.”

Moving to the U.S. with his parents at 13, Xu took to the American gun culture. He remembered holding a toy gun and screaming “AHHHH,” an image captured in his boyhood photo albums.

Growing up, Xu entered a more professional world through documentaries about war and firearms, forums, magazines and YouTube videos. He finally decided to buy his first gun on his 27th birthday – a GLOCK 34. Xu loves his GLOCK handgun. He carries almost every time he works in the gun club.

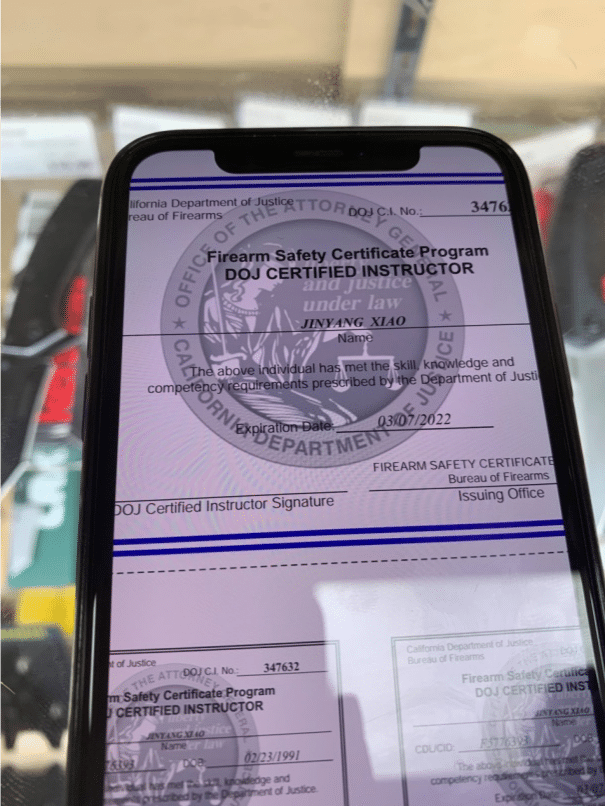

In California, firearm purchases require a Firearm Safety Certificate and proof of residency. You must be 21 to purchase any firearm. An exemption is made for those 18-20 years old who possess a valid hunting license to purchase long guns..

“I was like, ‘OH—’” Xu recalls the moment he held his first gun. “That’s one of the best feelings in my life. I felt my life was changed.”

But he only told his wife as he bought the gun. Before his work at the club two and a half years ago, Xu helped with his parents’ two gift shops. As a second-generation Chinese immigrant, Xu knew his parents’ worries on guns well.

According to the 2018 Asian American Voter Survey by APIAVote and AAPI Data, gun control has strong and consistent support among Asian Americans. By a nearly a 7-to-1 ratio, Asian American voters favor stricter gun laws in the U.S., with net support strongest among Chinese Americans and the foreign-born.

Culture plays into their attitudes, explains James Ma, Associate Professor of Information Systems from the Department of Business Analysis, University of Colorado. A Chinese green card holder living in the U.S. for over two decades, he is a gun fancier and attributes his fellow people’s worries about gun safety to Chinese stereotypes of masculinity in history.

Chinese in the Tang Dynasty, the most powerful period in history, aspired to military strength (wu), as noted by the orientalist R. H. van Gulik. But starting from the Song Dynasty, militarism gradually gave way to pacifism, with a “more refined, intellectual, masculine form” valued in the daily expression of self by Chinese men.

Born in the 1960s in China, Xu’s parents have always thought his job dangerous with meager salaries, emphasizing peace over violence in the traditional Chinese values. After Xu explained to them about American gun culture, they feared the firearms less and accepted his job at the gun club.

At the very beginning, Xu also felt uneasy and scared when pointed by undisciplined customers toying with loaded guns. He even quarreled with them and scolded them severely.

“Usually only gun enthusiasts stay,” Xu says as he overcomes the unfamiliarity and grows calmer. “If you just want a job, you may not be able to persist after a while.”

He then got his family into his hobby as well. Twice a year, he takes his father and his old friends to the Hodge Road Outdoor Shooting Area, a vast and free dessert in San Bernardino.

'My dad’s proud of me,' Xu says, smirking.

In summer, the temperature rises to 100 degrees. Under the scorching southern California sun, pieces of random shot-up machines and tires scatter among a sea of empty shotgun shells and steel casings. Brittlebushes curl; agave and yucca stretch their large rosettes of tough, sword-shaped leaves.

When the elderly are out of the boonies shooting skeet with shotguns, they will jump up in happiness and point the guns randomly, exclaiming, “Did you see that? I hit it!” Xu can’t bark at them, which is deemed as impolite in Chinese traditional culture, but grabs the muzzle firmly and teaches them to shoot properly and safely.

Gradually Xu’s father and uncles learned to love shooting under his guidance. Sometimes his uncle's place a target – an onion, watermelon or bowling pin – 80 feet away. They won’t listen even if Xu tells them it’s too far for them. As soon as they can’t hit the target, they blame it on Xu’s guns. Xu’s father will bristle, “It’s your problem!” and ask Xu to give an example.

“My dad’s proud of me,” Xu says, smirking. “He’ll shout [to his friends], ‘My son will teach you! No problem! No problem!’”

There is a ripple effect through his family and friends.

“I’ve influenced at least 10 people around me on their attitudes toward guns,” Xu claims, including his Shanghai wife who is better at shooting now. “I’ll get them interested in this and to turn it from an unfamiliar thing to a hobby.”

Young Blood

[dropcap size=big]X[/dropcap]u owns more than 30 guns and mostly buys guns via Calguns, an online forum for gun enthusiasts that offers second-handed firearms information. In California, private party transfers of firearms must be conducted through a licensed dealer, who is required to conduct a background check and keep a record of the sale.

One of the dealers Xu trusts is Gun Effects & Cloud 9 Fishing, a firearm store located in a City of Industry strip mall. Opened in 2012 by Dennis Lin, a Guangdong-born Chinese American, Gun Effects burgeoned from three showcases to a 530-foot spacious store, with 403 long guns hanging on three walls.

Seven years ago, business was slow due to cut-throat competition. Lin placed advertisements on ChineseInLA.com and spread leaflets over Chinese restaurants, but with limited help. In 2015, Chinese customers suddenly surged in the store and Lin said even he had no idea how this happened in an interview with the Los Angeles Times a year later. Since then, Gun Effects has evolved into the largest firearm store within the Chinese communities.

Justin Zheng, one of the store’s Chinese-speaking employees, attributes Gun Effects’ popularity with Chinese customers to its Chinese ownership and multilingual services, including English, Mandarin and Cantonese.

He also thanks the 2016 Times interview, “Now we still have customers who read the article three years ago and come to buy guns.”

In store for just four months, Zheng is a freshman at Mt. San Antonio College studying natural science part time. His thick black brows tilt upward under a black cap embroidered a label “SIG SAUER” – a German firearm brand. He wears a pair of square glasses and two silver, eagle-shaped earrings that flutter with his every move.

A week before his 21st birthday, he strives to appear more mature than his real age in a black T-shirt with a logo on the left chest, light-blue jeans, and a belt around his neck that ties to a smart key that controls the steel-bar front door. Even when we are talking, Zheng stays alert to anyone coming in or out of the store and presses the key whenever necessary. An unloaded handgun is placed in an olive-green holster around his waistband, which he often uses to explain certain details to me in a languid, sleepy voice. Though he sounds a bit absentminded, whenever I look into his eyes, he appears trustworthy and helpful.

Zheng’s first shooting experience in the U.S. dated back to 2017 in Utah. Without ear muffs, he was scared to death by the ear-splitting gunshots.

“It’s a fear of the unknown. The same as Thalassophobia,” he says, referring to the fear of oceans, though that’s not the first time he touched a gun.

Zheng has an unusual mother, who favored jobs with great responsibilities and wanted to become a soldier when she was young back in China. When Zheng was 10, she sent him to the Whampoa Military Academy for a half-month training, which was founded by Sun Yat-sen in Guangzhou, southern China, with Chiang Kai-shek as its first president.

Soldiers and policemen stood for real men to little Zheng, who was brought up in a single-parent family and has always dreamed of easing his mother’s burden. His uncle worked as a police officer in the Shenzhen Municipal Public Security Bureau, Guangdong Province, so Zheng could see him carrying a handgun on duty and would beg his mother to buy him toy guns.

He often compares a Glock to a Toyota or Honda.

Finally he was able to touch a real gun in military training, besides running around the playgrounds, practicing military boxing and watching patriotic war films. Every child was allowed to shoot two rounds with a handgun, accompanied by soldiers. But everything ended at such a lightning speed that Zheng didn’t even realize what had happened.

Before going abroad, Zheng went to boarding schools from kindergarten to junior high, all in a militarized and isolated environment. In 2015, he immigrated to Rancho, California. While his mother was busy with her cross-border business, Zheng had to study part time, responsible for his tuition fees and rent. Now he has entered college and works at Gun Effects, absorbing vast knowledge about guns from veteran employees.

As the current Chinese-speaking employee who works longest in the store (there are two other part-time workers only on Sundays), Zheng strives to improve the translations between English gun terminology and Chinese everyday language. He often finds it hard to “fact-check” whether a Chinese counterpart is “100% true.”

That’s when he turns to analogy for help or uses history as a “selling point.” He often compares a Glock to a Toyota or Honda, which is durable and has wearing parts easily accessible in the market. As for CZ, he explains its characteristics coupled with a history of over 80 years.

For self-defense, Zheng usually recommends a shotgun, a user-friendly type that sprays bullets and hits the target easily. For gun lovers, he understands their fondness of the guns used in films or video games such as Call of Duty and PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds. Some ask for a civilian-legal HK556 rifle in place of an HK416 for military use in the game, while others can recognize a Kriss Vector once they see it.

As public safety concerns sour over the past years, Chinese immigrants are learning more about their rights to bear firearms.

“You’ll always feel it’s far away until it happens to you,” Zheng says.

Aim High

[dropcap size=big]'A[/dropcap]fter you buy your first gun, you still don’t know how to use it,” Charles Xu says, “You may go to a range, you may watch videos on instructions, but you definitely need a professional to teach you…most importantly, about gun safety.”

For further firearm training, Justin Zheng refers me to Duke Xiao, a shooting instructor and a friend of Dennis Lin.

Xiao, 33, wears a dark pompadour that shows the outline of his broad forehead. His smiling eyes star with bristly black brows slanted downward, with protruding brow bones cutting a startling oblique line in his tanned face, and two jug ears shivering when he ends his sentence with a chuckle. He addresses with a good sense of humor that is neither too polite nor too glib and hopes his newly-shaved, slightly-stubbly round chin can make him “look younger.” Mostly covered under his warm-grey crew neck T-shirt, a pitch-black tattoo spreads over his broad chest in the shape of four dragons sinking and twisting claws with one another.

He believes the soaring dragons have brought him good luck, “I’m not superstitious. Sometimes if you have the right tattoo, it can really make you fly.”

Xiao immigrated to L.A. seven years ago. During the first four years, Xiao bumped around and made friends with people from all walks of life. With a military background, he found himself comfortable in the American gun industry. He then aspired to combine his preliminary thoughts of guns in China with the advanced technology in the U.S. Step by step he familiarized himself with the local gun culture, American shooting instructors, training agencies and servicemen.

At first, he strived to make the locals think Chinese can also shoot well by flexing his muscles. But soon he realized, “It won’t help if it’s just me doing ok. I have to take everybody with me.”

Xiao sees himself as a pioneer in L.A. Chinese-American shooters, too humble to admit he is “the No.1,” saying, “But if I can nurture just a couple of students who stand out later, I’ll be very happy.”

Years ago, he found as soon as the Chinese American shooters entered the shooting range, the Caucasians would stay far away. Without deeply-rooted safety instructions in mind, Chinese Americans got so excited when they held the guns that they walked around or posed for pictures with their unloaded guns pointing randomly. Xiao craved to change that negative image by improving gun safety awareness as well as shooting skills within Chinese communities.

In 2017, he founded 10-4 Tactical, a Chinese-language training agency, aiming high to “change Caucasian’s perception of Chinese American shooters.” The company name is a police code that stands for “Acknowledgement (OK)” and the logo is black-and-white in the shape of a badge with a Chinese traditional character “wei” that means “to defend.”

Xiao doesn’t choose to teach at the two other shooting ranges in Chino, San Bernardino County, where Chinese-speaking shooting instructors can be found in droves. Instead, Burro Canyon Shooting Park in Azusa, at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains in L.A. County, is more suitable for 10-4 Tactical, he thinks. The company’s target customers, 95% Chinese, are law enforcement (including some from China), military, tactical teams, civilians in L.A. and Chinese celebrities.

With only four Chinese-speaking Department of Justice certified instructors, the petite 10-4 Tactical has won an enviable reputation by offering professional, quality firearm education of all levels. They also teach at police academies, universities, large combat schools and community colleges.

'Can you reconcile it to your conscience?'

“This education will improve you as a practitioner and perhaps even as a person,” 10-4 Tactical writes on its website.

Xiao slightly adjusts American traditional shooting techniques he learnt in his first four years in L.A. in a way that fits Chinese customers more, explaining, “Our body structures are different. Their method doesn’t necessarily work for us. So I take the essence and discard the dregs.”

Customer Feng H. from San Francisco wrote in 10-4 Tactical’s Yelp page, “This is [the] best firearms training Institute runs by local Chinese American people. All instructors are well trained and have [a] lot of experiences with firearms and shooting.”

Xiao also takes an active part in professional competitions held by the United States Practical Shooting Association and helps students improve their marksmanship and rapid firing accuracy. This year, Xiao got third place in the USPSA HICAP National Championship and cultivated two apprentices. Other students from China enter practical shooting competitions in southeastern countries like Laos and Vietnam.

Loose Cannon

[dropcap size=big]B[/dropcap]esides training agencies like 10-4 Tactical, however, L.A. has a mixture of professional shooting instructors and fly-by-night coaches, with the latter taking up “80% among dozens of Chinese instructors,” Xiao estimates.

For one thing, incompetent instructors disrupt the market. They usually work on their own rather than in a company, taking shooting classes as a sideline, sometimes even without having customers sign waivers. They pass the National Rifle Association (NRA) certification exam, which, according to Xiao, can just prove they’re good at shooting themselves but doesn’t necessarily mean they are qualified to teach.

The unregulated coaches mainly cooperate with Chinese tour groups at a super low price to attract one-time visitors who don’t have the slightest idea of guns before. Some are even tour guides themselves who offer a one-stop service.

When the tourists have bad experiences, they’ll blame it on the entire training agencies in L.A., which makes Xiao feel wronged and complain, “They’re crippling the industry.”

Charles Xu echoes these feelings, mentioning there was a former employee fired by the L.A. Gun Club who boasted about his familiarity with guns but taught students negligently.

Xu says, “What can you learn from this kind of guy? Just basics. Nothing useful.”

For another, unprofessional coaches may mislead students who could lose their lives. Some instructors tell students to grab others’ guns in a wrong action, which, to Xiao, is playing with fire.

“Sometimes I’ll curse if I see them. 'How dare you teach others like this? If anything happens, you think you can walk away from it? Can you reconcile it to your conscience?'” Xiao says.

“It’s totally irresponsible making money in this way.”

Justin Zheng notes, “There are too many lax coaches now, but he [Xiao] is a reliable instructor.”

Aiming high, Xiao is satisfied with the progress 10-4 Tactical has made so far, “The [Burro Canyon] Shooting Park has always held a stereotype of Chinese Americans. But with our persistent work, now they grin once they see us.”

Every two weeks, Charles Xu goes shooting in outdoor ranges, choosing among the Oak Tree Gun Club, Angeles Shooting Range and Burro Canyon Shooting Park.

If he has kids in the future, Xu is more than happy to take his third-generation Chinese American children out shooting in the L.A. Gun Club and hunting in the deserts and woods.

He has suitable guns already.

For a girl, it would be a small pink Cricket, Xu’s first rifle; for a boy, it would be a Henry Golden Boy .22 Lever-Action Rifle, antique and west-style, like those used in the 20th-century cowboy movies.