[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]t’s been a little over a week since Morrissey performed in concert to a near-capacity crowd of faithful fans at the Hollywood Bowl. It was the penultimate stop on his latest California Son album tour.

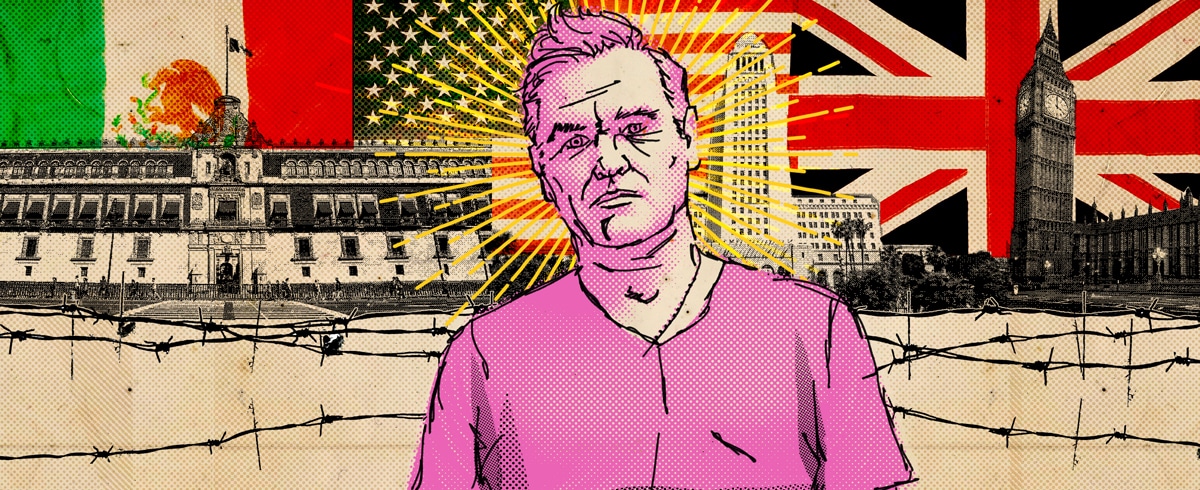

The Manchester-born singer came “home” to Los Angeles amidst lots of questions about whether his adopted-hometown fans should care about his For Britain politics and what those ideologies mean beyond U.K. borders, particularly in Trump’s America.

The last time Morrissey performed at the Hollywood Bowl, the Los Angeles City Council honored the singer by declaring November 10 “Morrissey Day” in L.A. The 2017 recognition made official what fans in the area have known for decades—that Los Angeles has been “too hot” for Moz since everyone’s tio, cousin, older sister, or girlfriend got them into The Smiths back in the 80s, and that Morrissey has “looked to Los Angeles” and the borderlands for his “new Latino heart” audiences ever since he stopped living in his native England in the 90s.

While Morrissey’s far-right politics is a provocative but fair starting point for a much-needed and honest fan discussion in 2019, especially amongst the generational and predominantly Mexican-American/Chicanx fans and culture of “Moz Angeles,” rehashing the “should fans care or not” and other polarizing dead-end questions no longer cuts it.

Where is the middle ground? What else can it look like to be a fan in Moz Angeles in a time of migrant detention camps, tear gas, and border walls?

On the heels of Morrissey’s recent Hollywood Bowl show, the upcoming two-year anniversary of Morrissey Day in L.A. on November 10, and a year after Morrissey co-headlined the Latin-music themed Tropicalia Festival in Long Beach in November 2018, I am after other questions that move us beyond “yes/no,” “love it or leave it,” “with us or against us” kind of fandoms.

Where is the middle ground? What else can it look like to be a fan in Moz Angeles in a time of migrant detention camps, tear gas, and border walls?

I don’t want to live in a Moz Angeles where we have to choose between totalizing platitudes like “love him or f*ck off,” or “just separate the art from the artist,” or abide by the belief that one is either a “Moz lover or hater” or either “gets Morrissey” or does not. I want space to think about what it means for Morrissey as a “California Son” to stand For Britain, to consider how and why some fans challenge him while not altogether tossing him out.

Somewhere between the faithful fans and the ex-fans are fans searching for something more. We can “have both,” we can hold critique with love (or something like it) precisely because of the complex and contradictory nature of Morrissey fans in the borderlands.

California Son For Britain

Most U.S. fans probably hadn’t heard of something called “For Britain” until the singer wore a party lapel pin on the Jimmy Fallon show in May 2019. The U.K. party wants to “Exit from the European Union,” “End Mass Migration,” “End the Islamisation of the U.K.,” and “Restore the Rule of Law” in the name of preserving U.K. national culture.

In interviews and posts in the months since the April 2018 endorsement, Moz has re-pledged his allegiance to this U.K. “forgotten majority” party best known for its hardline nation-first ideologies. Lesser-known party “Manifestos” include pledges to “end racist multiculturalism,” “gender propaganda,” and the “political indoctrination of children” in schools, as well as to “bar male to female transsexual students” from female sport competition.

What a pile of #MAGA.

For the most part, Moz Angeles fans seemed unbothered by these political affinities or if they are, have managed to separate art from the artist. Perhaps they insist that Morrissey’s “opinions” about immigration and Islam only apply to the U.K. and not us, not here, as if such ideologies don’t exist in other forms right here in L.A., California, and the U.S.A.

I find myself negotiating these sticky parts of fandom. Some days, it feels just like 1992 to me, when I was a bratty teenager blasting Bona Drag. Other days, I think about pinche 'For Britain' and that mock-up Tropicalia poster I saw floating around Facebook last year that called [Moz] “El Tío Racista.”

Other fans like myself can no longer ignore Morrissey’s political opinions. If only they were just that. A vocal endorsement of political parties and manifestos by a famous pop icon with a huge platform is hardly “just” an opinion. It is an informed and conscious political stance that speaks volumes.

Criticizing the Thing We Love

Finding middle ground in Moz Angeles is easier when we go back to one of Morrissey’s favorites, James Baldwin. The singer likes to project photos of the Harlem-born writer onto giant stage backdrops during his concerts. Baldwin’s image also appears on questionable Moz tour merchandise, and his face decorates Morrissey’s personal website.

One of Baldwin’s more oft-quoted lines comes from his 1955 collection, Notes of a Native Son: “I love America more than any other country in this world,” says Baldwin, “and, for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

...being a fan includes contending with “issues of disaffection, disidentification and the difficulty of negotiating one’s relationship with the object of one’s fandom.”

We can extend Baldwin’s logic to “criticize perpetually” the things we love, such as one’s country, religion, and even family, to seemingly insignificant, ‘less-important,’ things like those we love as fans—sports teams, film franchises, television shows, music icons, including Morrissey. Ask the Laker fans who wore Hong Kong solidarity t-shirts at the first game of the season as a challenge the star player on their own team about criticizing the things they love.

I found out last November at Tropicalia that I wasn’t alone in my torn fandom. Even then, one article wondered if “the Mexican-American Community Still Love Morrissey” just months after his For Britain endorsement. For me, the complex response to this question rivals another nuanced perpetual question pertaining to identity and pop culture in Los Angeles: Do Mexican-Americans in L.A. still love the Dodgers despite the ugly history that brought their stadium team to our city? Some do, some do not, and some find other ways to hold critical ground while accessing the joys of fandom, including nostalgia.

‘Nostalgia Is a Powerful Thing’

At Tropicalia, I met a few fans who had heard about Morrissey’s “latest” controversial views related to For Britain. Two friends from Guam who gave their first names only—Brandon, 35 and Anthony, 33—both expressed long-time Morrissey and Smiths fandom since their middle-school years. However, each of them expressed disappointment in Morrissey’s political statements.

“I loved [him] back then, but his views and the stands he has taken, that makes it hard for me to move forward with [him] as part of my life now.”

“I’ll say I’m a fan, but that’s all,” said Anthony. He explained his disappointment in Morrissey’s support for Brexit and what he described as the singer’s overall “anti-immigrant” stance.

“Music only goes so far sometimes,” added Brandon. “I’m here,” he continued, “but I have some reservations about him. I drove all the way from San Diego to see him. Nostalgia is a powerful thing.”

Another fan, Claudia Sánchez of Los Angeles, came to see Morrissey with her friend, Christine, “a Moz-head forever.” But Sánchez admitted a shift in her fandom. “I am Pro-Palestine,” she said, “and I can’t agree with his stance.” She refers to the singer’s decision to perform in Israel on recent tours, as well as his political party’s explicit anti-Islam, pro-Israeli-state platforms.

Sánchez understands fans like her friend, who “can’t let go of Moz because the fandom is their identity. So I understand how a person can’t let go so easily.” Finding middle ground for her means understanding the music’s importance to her life without giving up her current politics. “I’m a fan of the music. Those lyrics will always be with me, too,” she says with a sigh. “I loved [him] back then, but his views and the stands he has taken, that makes it hard for me to move forward with [him] as part of my life now.”

Like Sánchez and the others, I find myself negotiating these sticky parts of fandom. Some days, it feels just like 1992 to me, when I was a bratty teenager blasting Bona Drag. Other days, I think about pinche For Britain and that mock-up Tropicalia poster I saw floating around Facebook last year that called out “El Tío Racista.”

“We don’t think transnationally. A lot of the Chicanos I know do performative social justice—meaning Chicanos are down with the cause, to an extent. But when it comes to taking a stand, when it comes to [sacrificing] their comfort or leisure, folks aren’t willing to take it that far. They’d rather go see those bands they really like.”

I thought for sure that a disgruntled fan created the poster as a challenge, in the way I’ve seen other fans sell “Make Morrissey Great Again” shirts. Unlike that shirt, created by a fan in pain who begs the singer to be “less Trump and more Marr,” the mock-Tropicalia poster was created by an L.A. Salvadoran artist, Victor Interiano. He runs the page Dichos de Un Bicho, a Los Angeles-based Salvadoran cartoonist, and political commentator.

“I’m quite the opposite of a fan. But so many of my Chicano co-workers are, so it feels very personal,” said Interiano. He made the poster as a way challenge his Chicano Moz-fan friends, not only for their continued patronage of Morrissey and the “odious things” he says, but of Tropicalia itself, an event that represents the worst of what the 42-year old community organizer described Chicanos’ and Chicanas’ “first-world hypocrisy.”

“Groups fighting water privatization at the border wanted people to boycott Tropicalia because of its Constellation Brands sponsorship. And a bunch of Chicano bands were still playing anyway,” Interiano explained. “We don’t think transnationally. A lot of the Chicanos I know do performative social justice—meaning Chicanos are down with the cause, to an extent. But when it comes to taking a stand, when it comes to [sacrificing] their comfort or leisure, folks aren’t willing to take it that far. They’d rather go see those bands they really like.”

Interiano’s and Sánchez’s comments reveal that the limits of fandom often lie in its provinciality. We don’t think transnationally. But we live in L.A., a transnational, global city. How do fans not make cross-pond connections when the cultures, nations, and imperialist histories of the U.S. and U.K. are so intimately related?

You Are Not That Teenage Morrissey Fan Anymore

Last year around the Moz-Tropicalia moment, I spoke to Liz Ohanesian, L.A.-based music and culture journalist, and the first person I know of who wrote about L.A.’s Mozmania back in 1991. We discussed an earlier time, when the British press hounded Morrissey for waving a Union Jack at during a performance of “The National Front Disco” at the Madstock festival in 1992.

“As young fans in the 1990s, we didn’t have the cultural understanding of why the U.K. press was calling Morrissey a racist for waving the Union Jack,” said Ohanesian. “People wave flags all the time, so what was the big deal? The meaning was totally lost in translation to us. I understand it now, but back then, we just wanted to read about Morrissey in the NME that we had to pay eight bucks for and wait three months to get after it was published in the U.K.”

I had to skip the Bowl. As long as that “California Son” stands For Britain, then I’ll take a knee. And still, the “body rules the mind.” I smile as I pass by some record store or vintage shop when I hear “This Charming Man” spilling through speakers in Uptown Whittier.

Now that we’re older and maybe understand the complexity of the world a little better, what’s a fan to do? What do we do with this information, if anything? Finding “middle ground” for some may translate to seeing Morrissey as that problematic “uncle,” a handy way to write off or excuse some of Moz’s more troubling statements while chalking them up to “Chicano family” matters. He claims us, after all, as his own. Here’s Morrissey in his own words, taken from his book Autobiography. “I face my face. I wonder how they found me. All Mexican mellow, yet ready to put the chill on. Here in Fresno, I find it—with wall-to-wall Chicanos and Chicanas as my syndicate….For once I have my family.”

There is joy, pleasure, community, happiness, creativity, and other life-affirming energy to be gained from fandom. At the same time, media professor and popular music scholar Nabeel Zuberi reminds us that being a fan also includes contending with “issues of disaffection, disidentification and the difficulty of negotiating one’s relationship with the object of one’s fandom.”

Sometimes, There Are No Answers

As a queer Chicana scholar, author, and university profe of literature, ethnic studies, and women’s/gender studies in Trump’s USAmerica—and as a lifelong, deeply invested Morrissey fan— I am most angry about my favorite singer’s desires to see a political party in power that aims to reinforce a set of power relations grounded in singular notions of citizenship based on ideologies of exclusion and idealized notions of racial, gender, and political fitness in the nation. I teach against and work to undo such nationalist, nativist ideologies all the time.

“Mind rules the body”—I had to skip the Bowl. As long as that “California Son” stands For Britain, then I’ll take a knee.

“Just because he’s not talking about Latinos doesn’t mean what he says about other immigrants is not upsetting to me.”

And still, the “body rules the mind.” I smile as I pass by some record store or vintage shop when I hear “This Charming Man” spilling through speakers in Uptown Whittier. I still want “Cemetry Gates,” “First of the Gang to Die,” and “Everyday is like Sunday”—one of the most beautiful songs in the world—played at my funeral. The music is part of me, and I honor it.

Sometimes, there are no answers. Finding middle ground means sitting in the uncertainty of what to do with your fandom in the face of troubling news.

L.A.-based Mexican musician, Ceci Bastida, taught me this much. I reached out to Bastida, who sings and plays keyboards in Mexrissey, the Mexico City-based “supergroup” that performs ‘Mexified’ versions of popular Smiths and Morrissey songs. Mexrrissey toured the U.K. and Europe as recently as August 2018, not long after Morrissey made his comments about the London mayor and halal meat.

“It’s a bummer,” Bastida said, an immigrant. “Just because he’s not talking about Latinos doesn’t mean what he says about other immigrants is not upsetting to me.” Her fandom goes back to her teen years as a Smiths fan in Mexico. “I love the music, but it’s very difficult to separate the art from the artist. I don’t have an answer for it. But if one of his songs comes on the radio, I’m not going to turn it off.”

The writer wishes to thank L.A. Taco, Liz Ohanesian, Victor Interiano, Ceci Bastida, Adam Neustadter, and the fans who spoke to me with honesty, for their valuable insights and support while writing this essay.