[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he history of white supremacy and racist violence in Los Angeles is well known and well documented, from the Zoot Suit riots to the Lynwood Vikings, but it's still somewhat shocking to learn that one of L.A.'s mayors in the 1930s was also a leader of the local Ku Klux Klan.

California's racist history goes back to its entry into the union, and in fact, during the Civil War, the threat of California joining the rebels was so serious that Union authorities constructed a large military garrison outside Los Angeles to prevent the region from slipping into Confederate hands.

The Klan, a white supremacist terrorist group, was founded in the South immediately after the Civil War, but saw a revival in the early 20th century in other parts of the United States, including Southern California. Orange County was a national hotbed of Klan activity and success, to the point that in the 1920s, the Anaheim City Council was said to be almost entirely run by Klansmen. Southern California Klansmen were not the poor hillbillies portrayed in most depictions of the Klan, they were pillars of society, businessmen, police officers, and government employees.

Another important factor in understanding the Klan in Southern California is that racism was already the dominant political ideology. The white establishment, with very few exceptions, coalesced around white supremacy and agreed on the proper place for non-whites—as subservient labor, or as a problem to be contained.

The difference between a Klansman and a regular civic leader was not that one was racist and the other was not; the real difference in 1920s Los Angeles usually came down to either Catholicism, alcohol, mob ties, or all three. The Klan was both virulently Anti-Catholic, and a part of the temperance reform movement, which helped create and defend the 18th amendment to the constitution, banning alcohol.

Enter John Clinton Porter. Born in Iowa, he rose to local prominence as a virulently anti-Catholic and anti-Semitic Klan leader and close associate of "Fighting" Don Shuler. Shuler was a powerful fire-and-brimstone preacher operating out of the Southern Methodist Church, located at 1201 S. Flower St. in Downtown Los Angeles about a block away from where the Staples Center is now.

Shuler was a major figure in L.A. in the 1920s and 30s, with his radio program heard all over the state and into parts of Mexico, and his influential congregation that included prominent members of the city's establishment. L.A. Times wrote about him frequently, including this nugget from their archives in 1930: "Unless you have been attacked by Rev. 'Bob' Shuler, pastor of Trinity Methodist Church South, via radio, magazine, pulpit or pamphlet (25 cents per copy) you don't amount to much in Los Angeles."[6] Shuler's targets included the Los Angeles Public Library (for carrying books not fit to be read even in "heathen China or anarchistic Russia"), the YWCA (for conducting dances for girls "until the early hours of Sunday morning"), and other evangelists, including Billy Sunday and Aimee Semple McPherson."

Shuler and Porter represented a faction in Los Angeles that was deeply racist but also against "vice," primarily alcohol. Porter's racist background is not what got him voted into office, it was his campaign against the LAPD for being soft on alcohol and other vices such as prostitution. This was all bundled into the "reform" movement, which sought to limit corruption that was pervasive at every level in the city government. Los Angeles was known worldwide as a place where the police and the local government was corrupt in all aspects.

The reform angle was the only one played up in the most recent L.A. Times article on Porter's tenure, which was to last a single term. The 1997 Times piece doesn't mention the KKK membership, referring bizarrely to Porter's "xenophobic Protestant populism," but notes his stewardship of the 1932 Olympic Games.

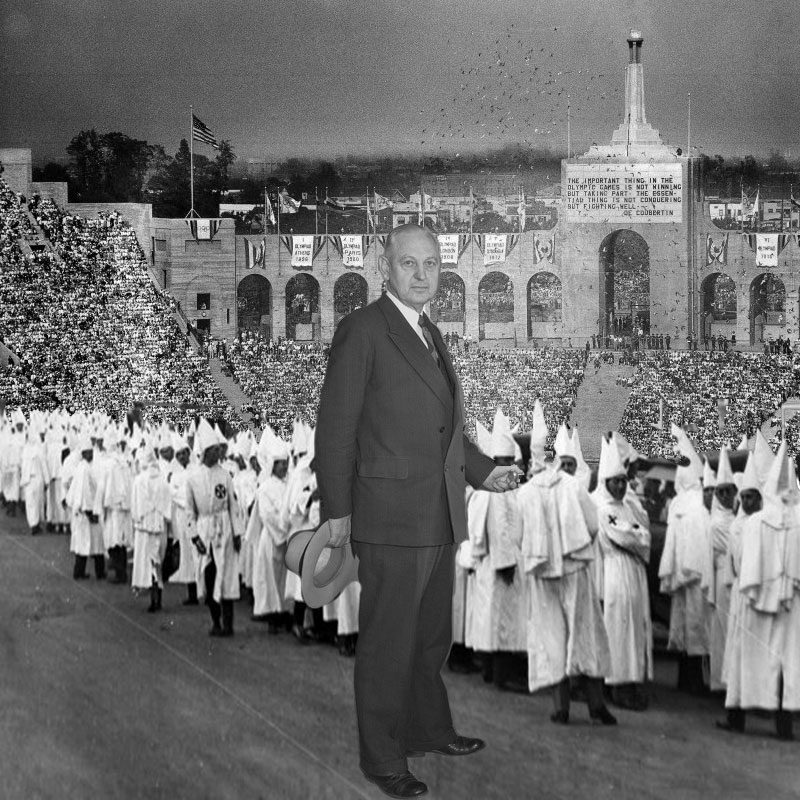

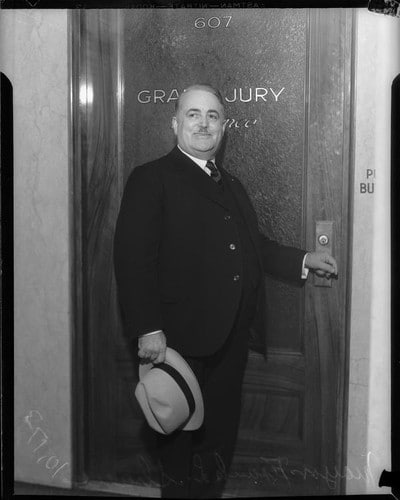

John Clinton Porter, Mayor of Los Angeles (right)

As mayor, he reportedly said, in response to a question as to why he would not appoint an African American to the Police Commission: “I cannot appoint a Negro on that commission, as I could not appoint a Catholic or a Jew or a member of other religious groups to certain commissions.”

Los Angeles and the KKK

At the time, the Ku Klux Klan was just one of the racist and fascist groups operating in Los Angeles, others included the Silver Legion, the Minute Men, and the White Guards. The Silver Legion built Murphy Ranch, which designed as a West Coast Nazi stronghold situated in L.A.'s Rustic Canyon.

In the 1920s, the city's entire function was divided along racial lines. Porter's ties in the KKK may make him unique in one sense, but in another, he was part of a long history of city figures who believed and perpetuated white supremacy as a foundational and systemic ideal.

The KKK's influence in Southern California peaked in the 1920s, and by 1946 the state revoked their charter as a legitimate organization. As early as July 1930 (during Porter's tenure as Mayor), Los Angeles Times reported that the Klan "has virtually expired as a going concern because of adverse public sentiment."

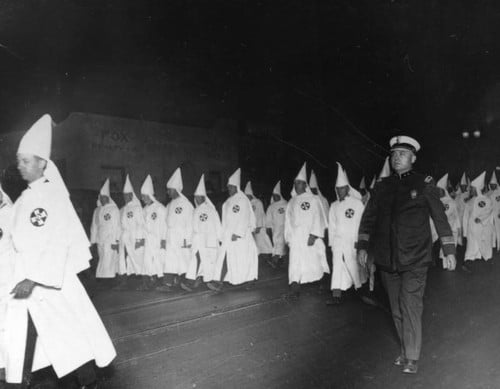

KKK on the march in Southern California. Photo via Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection

This stands in contrast to just one year earlier, when in June of 1929, as the city prepared to vote, Porter's opponent, William G. Bonelli, denied having ever applied to join the Highland Park branch of the KKK, saying it was a smear from the Porter campaign to muddy the waters. The article notes that the racist organization had "indorsed John C. Porter."

Bonelli had made the KKK past of his opponent an issue late in the campaign, saying "Shall we have four years of constructive co-operation in the upbuilding of Los Angeles, of which all can join... or shall we have four years of dissension, hatred, and bitterness, administered by a mayor indorsed for that office by the Ku Klux Klan, admittedly a former member of that organization?" It should also be noted that the Times did not endorse either Porter or Bonelli in their voter's guide.

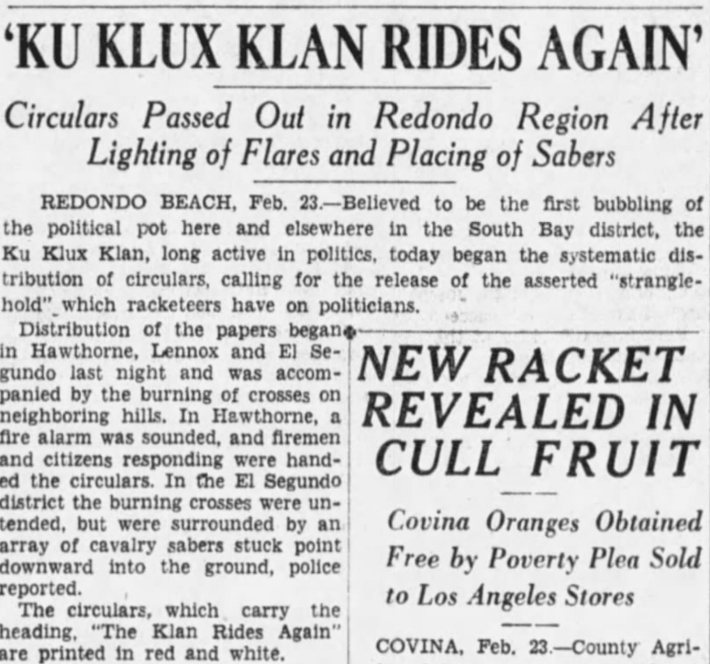

L.A. Times, February 24th, 1934

The Times' assertion in 1930 that the Klan was dying out proved incorrect, as just four years later in February of 1934, the paper reported that the organization "had long been active in politics" but had re-emerged in Redondo Beach, burning crosses around the South Bay, and handing out flyers with the headline "Ku Klux Klan Rides Again."

The Klan would eventually go underground, and the reform and temperance movements started to peter out. While Mayor Porter had a political high point when he presided over the 1932 Olympics in the rebuilt Coliseum, his low point may have come when he refused a Champagne toast while on an official trip to France, causing an international incident. The upright, moral Klansman refused to drink alcohol even abroad, as he claimed the US Constitution still applied to him.

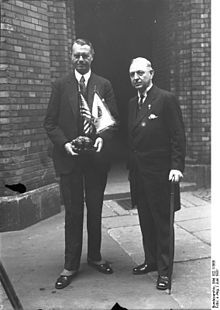

Frank L. Shaw, photo courtesy of UCLA Library Special Collection

On December 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment was ratified, prohibition was over, and Los Angeles was ready for a change. Democrat Porter was defeated by Republican Frank L. Shaw. Unlike Porter, Shaw (a former grocery clerk born in Canada who had moved to Los Angeles in 1909) had the support of the city's ethnic and religious minorities. More importantly, he had the support of the most powerful man in Los Angeles, L.A. Times publisher Otis Chandler, who was opposed to Porter.

Shaw quickly undid the reforms of Porter and put a system in place to run the LAPD like a corruption clearing house and personal extortion racket, going so far as to have the force bomb the Los Feliz home of a rival, Clifford Clinton, owner of the famous Clifton Cafeterias.

Just another year in the wild tales of L.A.'s mayors.