All Night Menu Volume Two is a book by Sam Sweet that explores the hidden histories of Los Angeles through addresses. Unknown legends, almost forgotten memories, and unearthed remains of micro-cultures populate its pages, including the following story the author has been gracious enough to share with us. The book was written, edited, and published in Los Angeles. Read our interview with Sam Sweet from last year, or visit his website at allnight-menu.com.

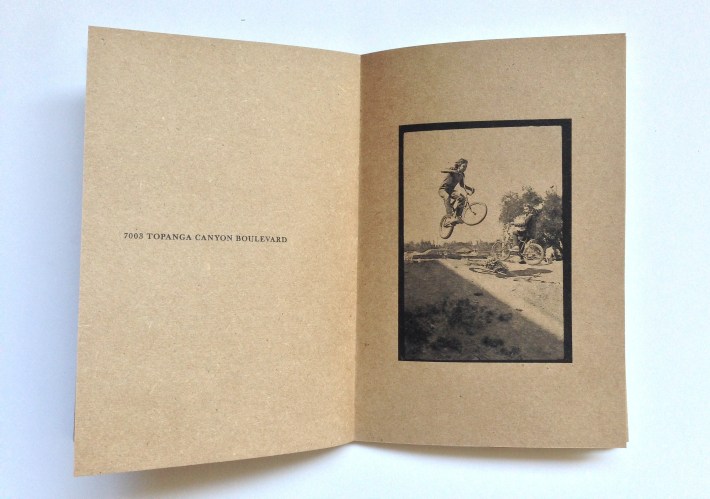

7003 Topanga Canyon Blvd.

When Bud Browne’s On Any Sunday opened in 1971, Mel Stoutsenberger and his friends rode their Schwinn Stingrays to every weekend matinee at the Topanga Theater to soak in spectacular footage of Belgian dirt bike idol Roger De Coster. Browne’s first non-surf film heralded the arrival of motocross in California. Incited by De Coster, the Valley kids would pedal west on Vanowen or Roscoe, where paved neighborhoods gave way to the rock-strewn hills above Canoga Park and Chatsworth. This terrain was sacred to the Chumash, whose lore told of Munits, the vanished shaman that haunted its caves. In the 19th century, Mexican usurpers renamed it Rancho El Escorpión. The vast ranchland was sold and apportioned in the 1960s, though suburban development was slow to arrive, leaving old horse trails open to bikes. “Once you crossed Valley Circle,” said Stoutsenberger, “you were in Ventura County and the cops would give up on you.”

First introduced in 1963 to capitalize on the L.A. custom craze, the Stingray afforded every nine-year-old the opportunity to own a chopper. Better yet, every frame came with Schwinn’s lifetime guarantee. Located at 7003 Topanga Canyon Boulevard, catty-corner to the high school, the Canoga Park Cycle Center was the biggest Stingray dealer in the United States. By 1971, it was developing a new reputation for having the country’s highest rate of frame replacement. Twenty-year-old shop manager Russ Okawa was a bright mechanic, as were his underage customers, many of them sons of engineers employed by Rockwell and Hughes Aircraft. When Okawa discovered the reason for all those broken frames, he drafted a team—10 boys from Canoga, eight from Woodland Hills—and supplied them with reinforced wheels of his own design. Each was metal-stamped with a number and the initials of Stoutsenberger’s friend Alan Johnson, who received the first pair. When word spread through Columbus Junior High School, Okawa couldn’t keep up with orders for “AJs.”

“Every kid racer in the San Fernando Valley got helped out by Russ,” said Stoutsenberger. His team smoked the competition at Indian Dunes and Soledad Sands, motocross meccas that hosted bicycle racing before the sport had a proper reputation. Okawa further modified the Stingrays by raising the bottom brackets and extending the cranks. Envious competitors cried foul and then copied his innovations. In 1974, Skip Hess, the father of a Simi Valley racer, introduced his Mongoose, the first bike explicitly marketed for off-road racing. Schwinn never regained its reputation, and the churchgoing Okawa was edged out of history. His insistence on clean language and matching uniforms clashed with the emerging sport’s image of itself. Santa Monica produced the first radical stars, though Stoutsenberger had to introduce the concept of downhill to the beach dwellers. Before that, he said, “they’d assumed BMX was something you did in an empty pool.” The term birthed an industry, but by that time most of the Canoga Park team had abandoned bikes for cars and “Valley Circle Estates” was offering homes from $625,000.

---