In Mexico City, tensions over soaring living costs, fueled by an influx of American and European 'digital nomads,' erupted when hundreds of chilangos protested in Roma and Condesa on the 4th of July weekend, targeting both foreign-owned and wealthy Mexican-owned businesses with vandalism to demand an end to gentrification.

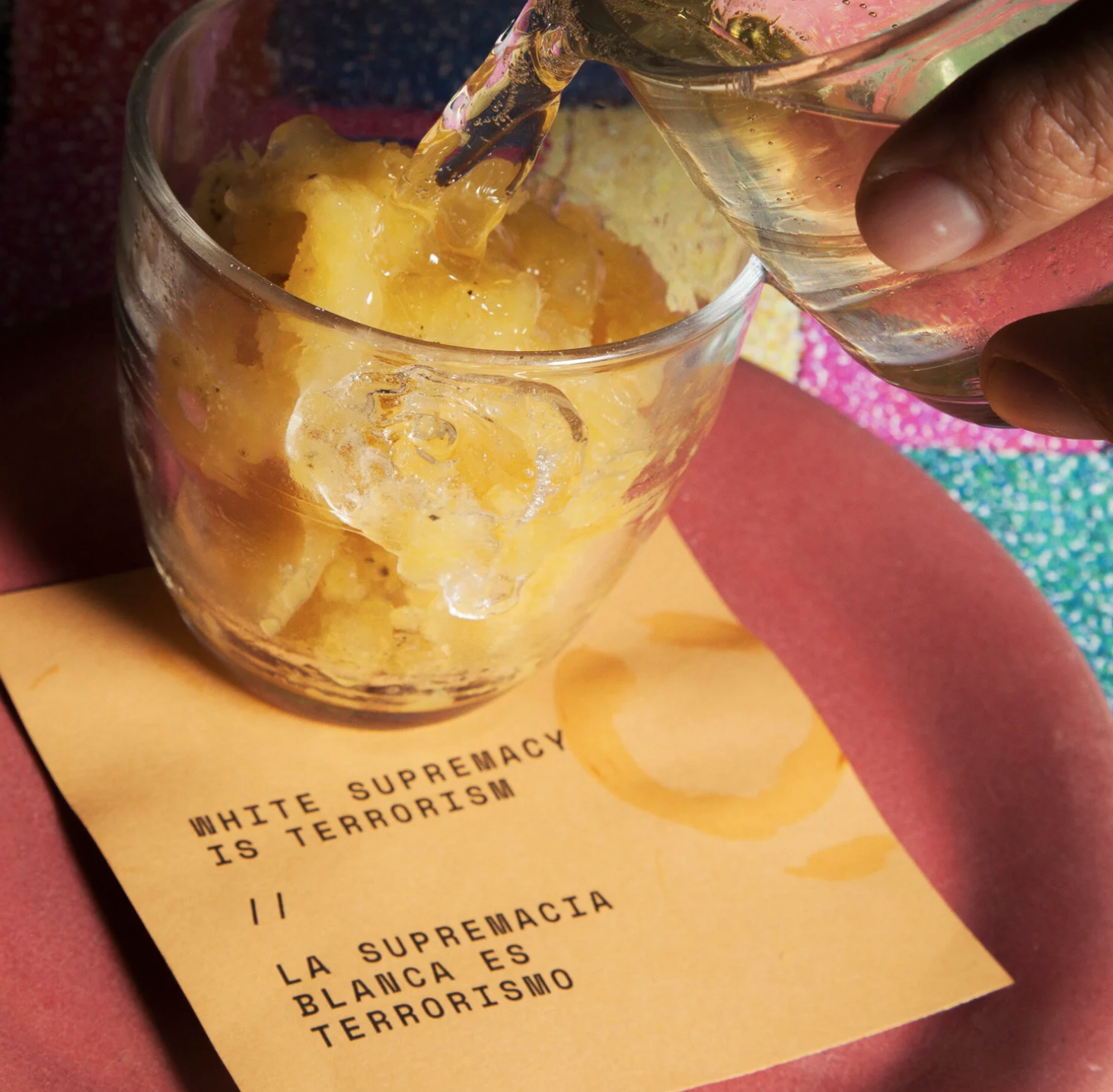

Saqib Keval and Norma Listman, the visionary chefs behind Michelin-starred Masala y Maíz, are bringing their pay-what-you-can model to working-class chilangos fed up with dollar-wielding expats driving up costs.

On August 27, they’re leading over 15 Mexico City restaurants—and global allies—in a bold stand against gentrification, daring the food world to make dining a right, not a privilege.

“It’s a small gesture with a big impact: An act of radical hospitality and trust that people respond to,” Keval tells L.A. TACO.

For one day, diners at nearly two dozen participating eateries can name their price for a meal, no questions asked—a radical act of benevolence in a metropolis where the cost of living is squeezing locals out.

A Michelin-starred restaurant is flipping the script on accessibility.

They've both hosted pay-what-you-can days multiple times a year at Masala y Maíz since 2017, aiming to make their innovative cuisine—born from generational responses to colonization and displacement—available to everyone. But this year, they're scaling up, sharing their playbook with other chefs and rallying a movement.

"We've confirmed over 20 restaurants and more are joining every day," Saqub tells L.A. TACO, listing heavy-hitters like Expendio de Maíz Sin Nombre (one Michelin star), Baldio (a Green Michelin star), Cicatriz, Mux Restaurante, Fideo Gordo, Ahumalia Smoke House, and others.

This initiative lands like a Molotov cocktail in a city boiling over with inequality.

Mexico City's cost of living has surged, fueled by gentrification that displaces longtime residents. Just last month, on July 4, hundreds protested in Roma and Condesa, chanting against "gringos" with euros and dollars buying up the country.

Demonstrators blamed digital nomads—mostly Americans and Europeans but also affluent Mexicans—for turning affordable areas unaffordable, with signs demanding foreigners "go home."

One protester lamented, "We're fed up with foreigners coming in ... there will be no one left to stop them."

The anger extended to landlords and government inaction, echoing similar outcries in Spain against Airbnb-fication.

Compounding the tension is the ironic reversal of migration flows. While Mexicans increasingly shun the U.S. amid immigration raids, mass shootings, and political turmoil, Americans are flocking south in record numbers.

Nearly two million U.S. citizens now call Mexico home, up 70% since 2019. Retirees, remote workers, and families are drawn to cheaper rents, affordable healthcare, and a slower pace.

But as one Tijuana chef told L.A. TACO, "I’m at a point in my life that I don’t care if I ever go to the U.S. again ... and I dare to say the way millions of Mexicans feel."

This exodus southward exacerbates local resentments, with "el boom gringo" driving up prices and cultural shifts without integration.

"We've seen how gentrification prices out the very people who make this city vibrant. This day is our way of pushing back, inviting everyone to the table on their terms."

In response, Mexico City’s mayor, Clara Brugada Molina, has unveiled a bold plan to combat gentrification, outlined in her July 16, 2025, "Bando 1: Por una Ciudad Habitable y Asequible." The 14-point initiative aims to stabilize rents, cap increases to the prior year’s inflation rate, regulate short-term rentals like Airbnb, and establish a Tenants’ Rights Defense Office. It also includes a "Master Plan" for high-pressure zones like Roma and Condesa, developed through citizen forums, and a push for 200,000 affordable housing units, with 20,000 public rental homes planned. Brugada emphasized, “The city must not be a privilege for a few, but a right for all,” signaling a structural fight against displacement that complements the grassroots efforts of chefs like Keval and Listman.

Against this backdrop, Masala y Maíz's campaign isn't just about food—it's a spotlight on benevolence as a business model.

"In a time when inequality is tearing communities apart, we wanted to show that restaurants can be part of the solution, not the problem,” Saqib Keval told L.A. TACO. “By letting people pay what they can, we're proving that accessibility doesn't mean sacrificing success—it's about building trust and shared humanity."

He added, "We've seen how gentrification prices out the very people who make this city vibrant. This day is our way of pushing back, inviting everyone to the table on their terms."

Keval and Listman’s vision draws from progressive precedents. It echoes a 2018 New Orleans food stall experiment by Nigerian chef Tunde Wey, reported by NPR in "Food Stall Serves Up A Social Experiment: White Customers Asked To Pay More."

There, people of color paid $12 for a meal, while white customers were asked to pay $30—reflecting the local racial income gap (African-American households earned 54% less than white ones)—with the surplus redistributed. Remarkably, 80% of white diners opted in, sparking conversations about privilege and disparity.

"The aggregate sum of all of our actions ... exacerbates or ameliorates the wealth gap, Wey noted.

This dining experiment begs to be theoretically applicable to Los Angeles, where gentrification in specific neighborhoods mirrors CDMX's woes. L.A.'s own experiments offer blueprints. Everytable, a mission-driven chain, prices meals based on neighborhood affluence—charging less in lower-income areas like Compton ($6-8) than in wealthier spots like Brentwood ($10+).

This sliding-scale model has sustained the business while feeding underserved communities, proving pay-what-you-can (or close to it). It's a subtle critique of initiatives like Dine LA, which offers fixed-price menus during restaurant weeks—a good start for democratizing fine dining, but limited in scope and duration, often excluding the most vulnerable and failing to address ongoing affordability crises.

Implementing a "Pay What You Can Day" in L.A. could be transformative, especially amid skyrocketing rents and food insecurity. Imagine spots like Kato or Holbox joining forces, perhaps with a racial equity twist like Wey's, where higher earners voluntarily pay more to subsidize others.

It wouldn't solve systemic issues, but as Keval emphasized to L.A. TACO: "It's about proving benevolence works. In L.A., with its immigrant roots and wealth divides, this could foster solidarity—reminding us that food is a right, not a luxury."

“Policy will change, hopefully, because of this,” Norma Listman, co-founder of this movement, wife to Keval, and chef of Masala y Maíz, told L.A. TACO.

Here are all the restaurants participating in Mexico City so far.

-Expendio de Maiz Sin Nombre

-Cicatriz Cafe

-Baldio

-Malix

-Mux Mexico

-Loup Bar

-Fideo Gordo

-Ciclo Mexicano

-Outline

-Ramiro Cocina

-Destello

-Mita

-Bao Bao

-Via Sol

-RUDO

-Sobremesa Desayunador

-Umani Fermentosx