There’s no denying that Los Angeles demographics have changed over the years. Gentrification has plagued some of the city’s most vibrant neighborhoods, and people of color continue to be pushed out of their homes and communities. And with the removal of these communities often comes the erasure of their stories, cultures, and history.

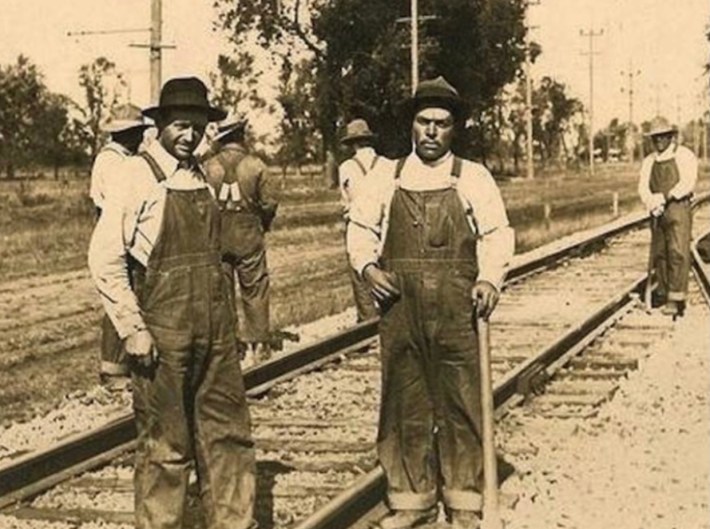

Because of this, a group of residents in Venice is looking to honor Mexican and Mexican Americans who contributed to the construction of the Main Railroad Transportation System. These railroad workers were better known as traqueros. Some were born in the U.S., and others migrated from different parts of México during the late 1800s. Their work and contributions to this country will now be honored and preserved with the installment of a monument in Venice.

“It’s something that is needed,” said the head of the Venice Mexican American Traqueros Monument Committee, Laura Ceballos. “In 2015, when I moved back to Venice, I noticed the gentrification, everything was very different, low income, Black and Brown people, were mostly driven out.”

The 51-year-old, born and raised in Venice, said she was inspired to advocate for creating this monument after noticing the change in her city and was also partially inspired by the nine-foot-tall Venice Japanese Memorial Monument on Lincoln and Venice boulevard.

“I saw how they were preserving all of their history, so I was like, hey, you know what? It's something that we should do because our history is being erased,” she said over the phone to L.A. TACO. “And there's nothing here that says we were here, we’ve been here, so we want to make sure we mark our footprint.”

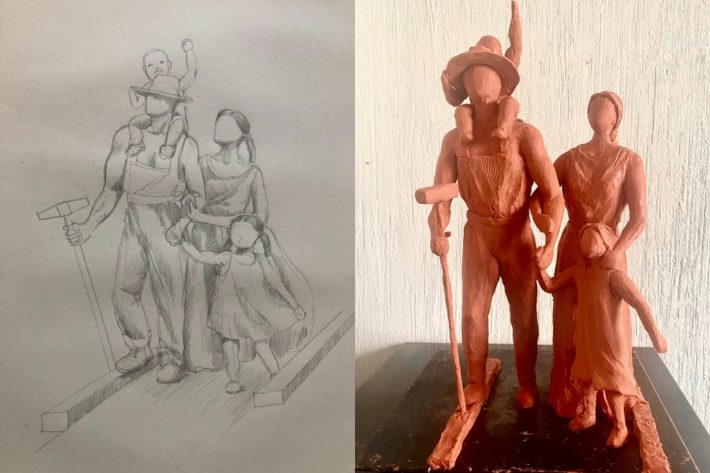

According to Ceballos, the monument that is set to be placed in Windward Circle will be the first monument in Venice representing Mexican and Mexican American traqueros. Francisco “Frank” Juarez, who is also part of the committee, said now is the time to “tell our own stories.”

“Venice is becoming snooty, and it’s important that the people coming in know that the very people that are the butt of their jokes and hatred are the very people who helped develop the nation and who continue to do so till this day,” he said.

For Ceballos and her team, having a physical representation of traqueros means acknowledging more than just the work done by them but also everything that came after. Many of the traqueros that came to work in the railroads eventually brought their families and settled in railroad camps located in Santa Monica, Culver City, and Pasadena. And although there isn't an exact number of how many Mexicanos worked in the railroads by the turn of the 20th century, Mexicans were considered the dominant immigrant laborer performing trackwork. Work documented in Jeffrey Marcos Garcilazo’s book “Traqueros: Mexican Railroad Workers In The United States.”

Ceballos explained how during that time, anti-Chinese violence and eventually the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 created what she described as a “high demand for low, cheap labor,” which prompted many to hire Mexicanos. Most of them were coming to the U.S. to find work or leaving their home country due to social unrest.

“It is very important that we educate the community because our history is embedded into the birth of L.A. and California,” she said. “As we all know, this [L.A.] was once part of México; we’re part of this American history, it’s in the name of our streets to the name of our cities, almost all are in Spanish.”

To keep their workers for more extended periods, traqueros were said to have been encouraged to bring their families to live in makeshift homes made out of old boxcars. Families that Ceballos said played an essential role in the life of traqueros. Women, in particular, are said to be the ones who “held it down,” aside from some of them working in the railroads, they also would often feed the workers.

Jose Preciado, a long-time Venice resident, remembers his grandfather’s stories from working as a traquero in the railroads. He tells the story of his father, Delfino Manuel Preciado, to his kids till this day, how he was born in one of the campsites in Oklahoma before ending up in California. His grandfather, named after Jose Manuel Preciado, originated from Guanajuato, México, and worked as a laborer laying tracks. He met his grandmother Ventura in the campsites, and she was one of the women that would bring food to the workers.

“Tacos wrapped up in a canasta (basket,) that’s how he met her, the women would make food, that was easy to make and easy to store, and they would go and distribute them,” said Preciado reminiscing on the stories he heard growing up.

Because of this, the 73-year-old was happy to hear about the bronze monument, including a traquero and his family beside him.

“That’s how it was, both my grandfather and his brother worked as traqueros in Oklahoma and Santa Monica, and they created their own families there, so I’d say it’s a great way to honor the families that came and the families that grew on those tracks,” said Preciado.

His father and grandfather left him with many stories from that time, like how the workers and their families often relied on each other’s different cultural, natural remedios (remedies) to heal many sicknesses. Or how it’s rumored in his family that his grandfather funded the Mexican Revolution when sending money to one of his brothers, who is said to have hung around legendary Pancho Villa and his people.

“My grandfather used to front some money to his brother who obviously used it to buy arms and ammunition and stuff like that for the revolution,” said Preciado.

He said he is proud of his grandfather and what he could contribute to the development of the railroads. Saying that if it weren’t for his job laying tracks, he and his siblings probably wouldn't be here, not just in LA but here, because his grandfather would have never met his grandmother.

Stories like Preciado’s family are the type of stories Ceballos and the committee want to honor.

The monument has garnered the support of the LA City Council, who voted last year to proceed with the installation of the bronze statue designed by Mexican artist and sculptor Jorge Marin. Ceballos said despite a bit of push back from “gentrifiers and racists,” the overall response from the community has been great. And although the statute is set to be completed by 2024, Ceballos and her team are hoping to continue to spread their knowledge and findings with their community to learn from other families who may have settled in L.A. due to the railroads.

“I want to stress that although the monument will be on the Westside, the tracks were laid all over, the monument represents all of L.A.,” she said. “At the end, people want to see things they can identify with, and they want to see themselves reflected in their history books and in their cities.”