One night, when director Gregory Nava was filming under the 4th-and-Lorena Street Bridge in Boyle Heights, a tragic tie to the past unwittingly became part of the present. It was a cosmic connection so undeniable that even 30 years later it gives the director chills when recounting the story.

Nava was filming a pivotal scene for Mi Familia, his intimate yet sweeping multi-generational portrait of the struggles, joys, losses, successes, heartbreaks and reconciliations within a Mexican-American family living in East L.A. The scene in question involved the horrific shooting death of one of the film’s polarizing main characters at the hands of police just steps from his family’s home.

While filming night after night at the historic bridge, Nava began to notice a man quietly watching from the sidelines. He kept to himself and never disturbed anyone, but he observed intently as the cast and crew moved from setup to setup.

The director was curious.

“Finally, I went up and I talked to him,” Nava told L.A. TACO in a recent interview. “I said, ‘You’re always here every night, and you’re sitting here and you’re watching all of this.’”

Nava recalls the contemplative bystander saying, “‘You’re showing it. You’re showing what happened.’ I go, ‘What do you mean?’”

He continued to tell Nava about a man who was killed by police under the Lorena Street Bridge in the 1950s. His name was Chuy; The character in the film, played by Esai Morales, was named Chucho. The scene also took place in the 1950s.

“He thought we were recreating something that actually happened,” says Nava. “Now, I didn’t know anything about that. And I didn’t write the scene with that in mind. And I didn’t pick that location with that in mind.”

It was transcendental.

It was as though Mi Familia was predestined to become the cultural touchstone that it is, even though the script had been turned down by every studio in town.

Mi Familia roughly spans 65 years. Its framework is largely shaped by the perspective of Paco (Edward James Olmos), the eldest of the Sanchez family’s six children. The former Navy officer turns to chronicling his family’s story beginning in the 1920s with the emigration of his father, Jose (Jacob Vargas), from a village in Michoacán, Mexico to another village far to the north called Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles—“the one in California.” There Jose meets and starts a family with the love of his life, Maria (Jennifer Lopez).

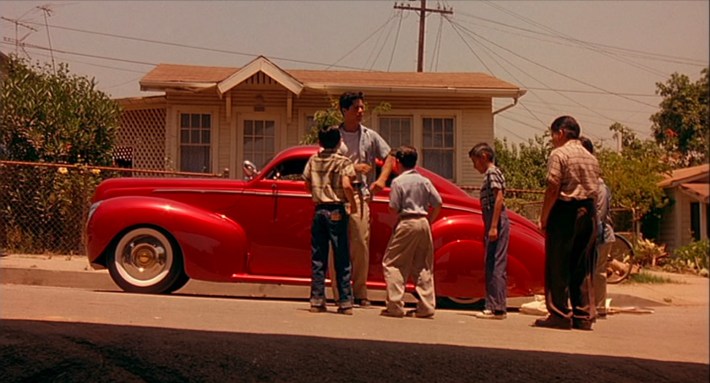

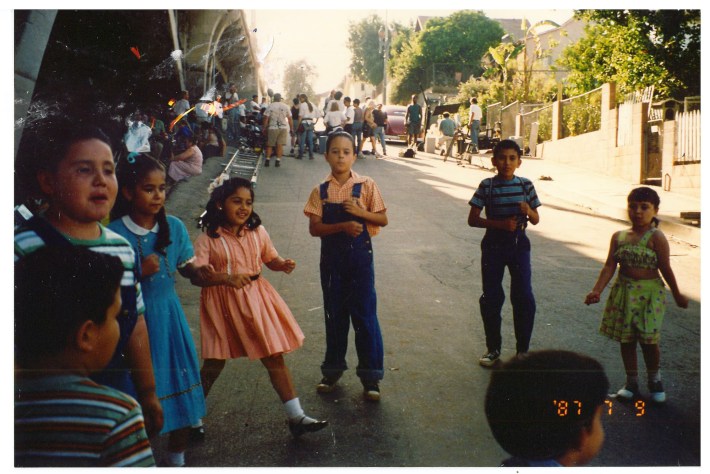

The film is punctuated with a number of joyful and humorous moments. Among them is a scene in which Chucho teaches the neighborhood kids to mambo in the middle of 4th Street. It’s a celebration of life in the barrio.

That scenario and others are offset by points of unbearable pain and despair.

A young Maria is illegally deported while pregnant with Chucho. Determined to return to her family, Maria sets off with her newborn on an arduous and perilous journey from Mexico back to East Los Angeles.

Additionally, the aforementioned death of Chucho triggers a traumatic downward spiral for his younger brother Jimmy (Jimmy Smits).

As the story unfolds, Los Angeles grows into a sprawling metropolis that is literally and culturally built on the backs of immigrants and their families.

“The studios just don’t want to make movies about these things,” says Nava. “It’s very hard to get Hispanic/Latino films made in Hollywood.”

It wasn’t until the script landed in the hands of revered filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola that the picture had a chance of being realized.

“He said, ‘I love your script and I want to get this movie made,’” recalls Nava upon his initial meeting with Coppola in Napa wine country.

Nava told Coppola that of all the studios that passed on the project, New Line Cinema expressed some initial interest. Coppola told Nava to be at his San Francisco office the next day.

When he arrived there the following morning, Nava sat down as Coppola went into his office, closing the door behind him.

“He called up Bob Shaye, who was the head of New Line, and of course he immediately took Francis’s call. They bonded over wine,” says Nava. “Forty-five minutes later, he came out and said, ‘Okay, your movie’s a go.’”

Coppola, who executive produced the film, gave Nava complete creative freedom and sent him a telegram on the first day of principal photography.

“That telegram was, ‘Go make your film and make a great movie,’” Nava says. “If it hadn’t been for Francis, there wouldn’t have been a Mi Familia.”

The film was released on May 3, 1995. In the years since, it’s become an L.A. classic. In 2024, Mi Familia was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry. It joined the company Nava’s El Norte (1983) and Selena (1997).

Like Boulevard Nights (1979) and Born in East L.A. (1987) before it, Nava didn’t explicitly call the neighborhood Boyle Heights in the film.

“Just for the audience in general and worldwide you say ‘East Los Angeles.’ It has an identity of which people immediately conjure up in their minds and you don’t have to explain anything,” says Nava. “People think of the whole area as kind of East Los Angeles, not the actual geographical nomenclature, but as the cultural unit.”

A number of Boyle Heights locations were used in Mi Familia including the old Linda Vista Community Hospital on the edge of Hollenbeck Park; Paco’s house, which overlooked the downtown skyline from Pennsylvania Avenue; Jimmy’s apartment on Ganahl Street near the border of City Terrace; there are shots of Jimmy walking along 1st Street between Savannah Street and Evergreen Avenue near the El Tropico nightclub. Today the block is almost unrecognizable from how it appeared in the film.

But the anchor of Mi Familia is the Sanchez family home.

The house starts out as an earthy, rustic cabin belonging to Jose’s distant relative Don Alejandro Vasquez, a cantankerous old man with a soft spot for family who was born in California when it was still Mexico, hence his moniker, El Californio. The house is later left to Jose when the old man dies.

As the Sanchez family grows, so does the house. It takes on a life of its own as the characters age and develop. It becomes more and more colorful, reflecting the personalities that reside within. It almost feels like a grounded precursor to the magical Casa Madrigal in Encanto (2021). As time goes on, however, the color also fades.

Watching over the house from the very beginning is the majestic Lorena Street Bridge.

Within the context of the film, the bridge would have been brand new upon Jose’s arrival in Los Angeles.

The reinforced concrete viaduct, which replaced an antiquated wooden structure, covers the split grade of Lorena Street and connects upper East 4th Street between Lorena and Concord Street. At a cost of $275,350, it was the first bridge on the Eastside to be completed under the $1.9 million Viaduct Bond Act, which was approved by Los Angeles voters in 1924. It opened to traffic and pedestrians in early September 1928; a formal dedication took place a month later. Upon its opening, the Lorena Street Bridge was touted as an essential artery that was crucial for the rapidly expanding Eastside.

Cinematically, the location is an ideal symbol for the evolution of Los Angeles and a potent metaphor for how the characters’ arcs are inherently intertwined with the city’s growth. It also furthers a visual motif that is present from the opening frames of the film: the bridges spanning the L.A. River, a border over which Eastside residents cross everyday, but people on the opposite end never traverse.

Nava was born and raised in San Diego—he calls himself a “border guy” - and spent a lot of time visiting relatives in Tijuana.

He also had family scattered throughout Southern California, and he spent a good deal of time in Boyle Heights, where his grandmother, Sebastiana, settled upon emigrating to the United States. She would cross the bridges everyday to work as a maid for an affluent family, which is almost identical to the film’s introduction of Jennifer Lopez, who was starring in her first major film role.

Considering Nava’s relationship with Boyle Heights and how much screen time the Sanchez house and Lorena Street Bridge receive—nearly half of the film’s 126-minute running time—it’s somewhat surprising to learn that he didn’t write the screenplay with the bridge in mind. It only was upon scouting it that it became central to the film.

“Location is so supremely important in film, and you want to have a visual that just says what you want to say,’ says Nava. “The minute I saw the bridge, I knew that that was what I wanted,” says Nava.

The Lorena Street Bridge had previously made appearances in films including Boulevard Nights, Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984), and Colors (1988), but it was Mi Familia that employed the location as a full-fledged character.

“When I saw this location for that Lorena Street Bridge, a lot of things came to my mind,” says Nava. “I not only saw a magnificent location to be the establishing of where the house was, but also an incredible place to stage the shooting of Chucho by the police.”

The masterfully crafted sequence comes after Chucho has murdered the leader of a rival gang at a community dance hall.

One evening, as the Sanchez family watches I Love Lucy in their living room, Chucho is forced to abandon his hiding place when a cop discovers his whereabouts. He is chased back to the underbelly of the bridge and shot in the head in front of his preadolescent brother.

Nava wanted the sequence to feel like “dream-realist film noir,” and drew inspiration from the nightmarish frescos painted inside the chapel and vaulted dome at the Hospicio Cabañas in Guadalajara in the late ‘30s by Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco.

The arches of the Lorena Street Bridge are also suggestive of the vaulting architecture seen in the chapel of the Hospicio Cabañas.

Under the wash of a deep blue glow that is repeatedly pierced by the flashing red light from a police car, Chucho lies dead on the dirt amongst scattered garbage and broken down cars. The faint sound of brass instruments, maracas and conga drums from the I Love Lucy theme can be heard reverberating under the bridge as dogs bark in the background.

“When I Love Lucy was on - and I remember this - and you went outside your house, you heard I Love Lucy because every house in the neighborhood was watching it,” says Nava.

The beloved classic sitcom was filmed just ten miles to the west of the Lorena Street Bridge.

He adds, “I thought what would be a tremendous counterpoint to this particular scene would be that irony of hearing this music, this idealized idea of American life at that particular time period, clashed against the horrid street reality of the police brutality and oppression of the Chicano community in East Los Angeles.”

Today, a visit to lower 4th Street near the Lorena Street Bridge is to walk on historic, cultural and cinematic hallowed ground. But the one thing you might expect to find there survives only within the frames of the film itself.

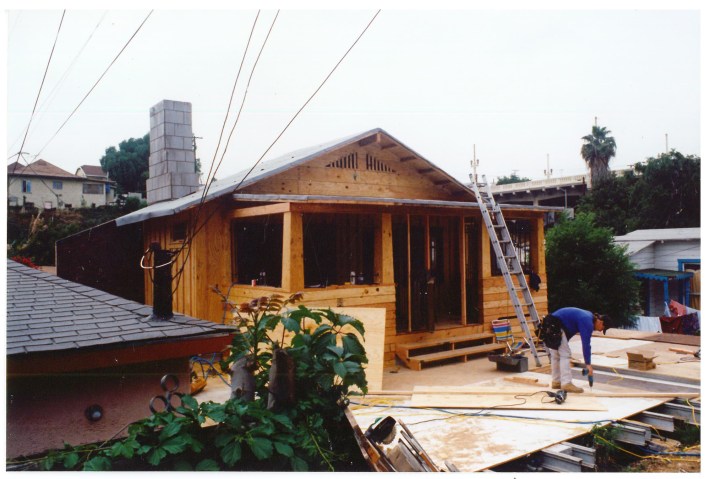

“We thought, ‘Oh, this is a great location,’ but we needed the house,” says Nava. “All the work that we had to do—flying walls because we had these long shots and all this kind of stuff - you couldn’t do at a real house.”

A fully-realized version of the Sanchez home was built at Saddlerock Ranch in the Santa Monica Mountains adjacent to Agoura Hills prior to it becoming a vineyard.

The Saddlerock Ranch website shows photos of the house remaining intact on the property years later. Various wine and style blogs reveal that at one point the set was used as the main office for Saddlerock’s Malibu Wine Safaris, which faced legal scrutiny in 2021 and is today reportedly closed.

Only the facade of the house was built in Boyle Heights.

“Sometimes the exterior scenes of the house were shot at the Lorena Street Bridge and sometimes they were shot at the set,” says Nava. “They did such a perfectly good job of replicating the facade, you don’t know which house you’re at.”

For the vibrant aesthetic of the house, Nava was again inspired by art from the past, but it was a past in which parts of the film take place. He looked to the Chicano Art Movement.

“I thought, I’m going to hire a Chicano artist to paint paintings of the house to inspire the production design of the movie and how the house changes over generations,” says Nava.

The director hired East L.A. native Patssi Valdez, who was a founding member of Asco, the Eastside art collective that was active from 1972 - 1987.

Valdez’s “previs” paintings of the Sanchez house, which today hang on the walls of Nava’s office, are full of the vivid colors that are reflected in the final film. Walls of magenta, midnight blue and pine green connect in two-dimensional splendor across a canvas. Off-balance table lamps cast golden mists of incandescent light, and a motley collection of wooden chairs in various hues is situated around a dining room table.

In order to film at the Lorena Street Bridge, Nava says the production agreed to feed members of the neighborhood’s deeply rooted White Fence gang. It put into perspective some of the hardships facing this underserved part of the city.

“It made me think, because these guys were starving. They were all hungry because they hadn’t eaten,” says Nava. “That’s really fundamental, isn’t it? So we were happy to open our catering up to them.”

The production also hired White Fence members as security and to act as liaisons within the neighborhood. The film’s end credits include thank you’s to “The Fellas of White Fence” and “the Neighbors at 4th Street and Lorena Avenue [sic], East Los Angeles.”

Thirty years later, Nava says that whether it was during the production of his PBS series American Family (2002 - 2004), or it was taking film-industry friends—Guillermo del Toro being counted among them—around East L.A., he’s occasionally revisited the main location from Mi Familia. But the emotions that surface upon returning to the Lorena Street Bridge run much deeper than timeworn nostalgia for a filming location.

“As a kid, I was going to Mexico twice a week. People are speaking Spanish. Then you’re going to East L.A. and that’s not like Leave it to Beaver or a Frank Capra movie. I just have a whole different perspective of the culture and the politics and what a border means and what a country means,” says Nava.

“I wanted to show in Mi Familia that this place wasn’t always the United States,” he adds. “The heart culture of Los Angeles is Latino. The Anglo is more powerful, richer—you know, Hollywood. But it’s still superimposed over a Latino culture.”

Nava says that Boyle Heights has changed since he made Mi Familia and that gentrification threatens the neighborhood’s very essence.

Unchangeable, however, is the commanding presence of the concrete viaduct at 4th and Lorena that has spanned generations and retains the uncanny ability to connect with a people’s past, as Nava experienced first-hand that night under the bridge.

“When you make a movie, there’s so much going on that even you don’t understand, and nobody understands. There’s some psychic energy that’s unleashed,” says Nava. “And there’s so much more to what the making of a movie does to the people who make it and the people who you make it about.”

Follow Jared on Instagram at @jaredcowan.