[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]n mid-February, my location manager friend David Lyons texted a selfie in front of a monumental domed building situated at the end of a residential street, palm trees protruding from the middle of the broken blacktop. Accompanying it was a corresponding screenshot of the location as it appeared on screen nearly 37 years ago. This was Miracles community center from Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo.

Lyons and I met in 2019 while driving around town looking at the locations from Dolemite Is My Name, on which he worked as location manager. We both nerd out over locations from the most acclaimed L.A. films to the most esoteric, so he knew I’d dig the shout out to the 1984 breakdance movie.

“There’s something magical about standing in the spot where they shot Citizen Kane; there’s also something magical about standing in the spot where they shot Breakin’ 2,” Lyons later told me.

Our text exchange sent me down the Electric Boogaloo rabbit hole, and I was reminded that beyond the florescent spandex and the saccharine storyline is a narrative of community. In 1984, New York had Beat Street, L.A. had Breakin’ and Breakin’ 2.

Both Breakin’ films were produced by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, aka Cannon Films, the team behind such wonderfully campy and gratuitous ‘80s fare like The Apple (1980), New Year’s Evil (1980), The Last American Virgin (1982), Masters of the Universe (1987), and the Stallone-starring one-two-punch of Cobra (1986) and Over the Top (1987).

Where Breakin’ is all about taking street dance mainstream, Breakin’ 2 is just the opposite. Picking up shortly after the events of Breakin’, we find our heroes Ozone (Adolfo “Shabba-Doo” Quiñones), Turbo (Michael “Boogaloo Shrimp” Chambers), and Kelly (Lucinda Dickey) trying to save a humble community center from being bulldozed by a villainous commercial real estate developer. In a race against time, they have to raise $200,000 to save the building and the future of the neighborhood’s underserved youth.

Breakin’ 2 director Sam Firstenberg tells me that the idea of taking the sequel to the streets was the brainchild of Quiñones, who was a central figure in the popularization of hip-hop dance. “This was his vision,” says Firstenberg. “He wanted more of a social commentary.” “Shabba-Doo,” Quiñones’ performing moniker, passed away last December at the age of 65, shortly after posting a message on Instagram that he was getting over a cold and had tested negative for COVID-19.

It was critical for Firstenberg to shoot Breakin’ 2 in a neighborhood where hip-hop dance was actually taking place. Though East L.A. wasn’t the only backdrop considered for Breakin’ 2, it was the most natural.

“Whittier Boulevard, with the cruising, people would just park their cars or walk up and down Whittier Boulevard, and if they saw another rival [dance] crew, they’d start battling on the streets with their boom box,” says Michael “Boogaloo Shrimp” Chambers. “In Boyle Heights, the dances popping and locking, those were very popular,” he adds.

Firstenberg got involved in the script’s writing about halfway through the process, and while the core ideas were already in place, the director’s personal history found its way into the story. During the 1950s, the Polish-born Firstenberg grew up in Jerusalem, where he and his family lived in the German Colony, a neighborhood comprised of Jewish immigrants from all over the world. “The colorful feeling that you later see in Electric Boogaloo was my childhood. I grew up with different foods, different smells, different languages,” says Firstenberg. “I don’t want to be too psychological here, but in a way, it reflects itself in the neighborhood of Boyle Heights.”

“East L.A. was a melting pot. I think, for us, it had validity because, obviously, I was African American, but my girl [in the movie] was Latina, “Shabba-Doo” was Latino,” says Chambers, who was brought up in Wilmington and started dancing in the Long Beach area. “So I think it was politically correct that Ozone and Turbo would be in Boyle Heights.”

Unlike film professionals who are often inspired by L.A.’s vast expanse, Firstenberg is somewhat critical of the city’s landscape. “Los Angeles is flat and not very cinematic,” says the director, who shot most of his films, including other Cannon movies like American Ninja (1985), Ninja III: The Domination (1984), and American Samurai (1992) outside of L.A. “You go to the Valley. It’s flat, straight streets; they go on forever.” Boyle Heights, however, was an inspiration, and the director fell in love with it. He says, “You have hills, ups, and downs. The streets are curving. You have history.”

Breakin’ 2 production designer Joseph Garrity says Boyle Heights’ hills can be interpreted as a metaphor within the film’s confines. “It was part of the visual journey of the ups and downs of their mission and what they had to do,” says Garrity.

Breakin’ 2 assistant location manager Marshall Moore says, “From the way the sidewalks were, to the streets—some of them narrow, some of them a little wider, some of them overgrown—small, bungalow-style houses, [Boyle Heights] lent itself in keeping with the story.”

Thirty-seven years later, there are conflicting recollections about the order of events that centered the production Boyle Heights. Firstenberg says that most of the Boyle Heights locations had been chosen before he stumbled upon Casa Del Mexicano, a real community center that would be transformed into Miracles. On the other hand, Moore says that Casa Del Mexicano had already been chosen to join the project. He was charged with finding the peripheral East L.A. locations based on their proximity to the community center.

“The location people were showing me this building, that building, this church that used to be a synagogue, another church that used to be a synagogue, and some of them looked really fine, but not the exterior,” says Firstenberg. On weekends, the director and his assistant director would drive Boyle Heights’ streets to get a feel for the neighborhood in which they were filming. One day while driving north on Euclid Avenue, Firstenberg looked to his left and saw at the end of a cul-de-sac, standing by itself, an impressive structure with a grand staircase, Greek Revival façade, and a domed roof that soared above the surrounding homes. He immediately knew that Casa Del Mexicano was perfect for Miracles.

Moore, who worked as a production assistant on the first Breakin’, says a deal was made to take over Casa Del Mexicano for a couple of months. “[Location manager] Tim Healey and myself kind of took over as the building managers. My daily call times were probably between five and six a.m., and I would open up the building every morning,” says Moore. “That became my office.”

The location’s portrayal on-screen isn’t far removed from its real-life history. The building was opened in 1904 as a Methodist church, later becoming a Jewish synagogue. Casa Del Mexicano was established in 1931 for Comite de Beneficencia Mexicana Inc. This nonprofit entity assisted Mexican citizens who were being deported, having been accused of stealing American jobs during the Great Depression. Similar to its depiction in Breakin’ 2, Casa Del Mexicano later provided a space for education; it was a linchpin for community organizations and fundraisers. By the ‘90s, the location began to deteriorate as various parties became more concerned with controlling the property rather than its upkeep. In 2013, the LA Times reported that a married couple took over in 2004, claiming to run it as a nonprofit, but it was thought that they were making money from various events renting the property. The building was in danger of being foreclosed upon after taking out a $175,000 loan against the historic community center. In 2012, affordable housing developer East LA Community Corporation was awarded stewardship of Casa Del Mexicano by the state attorney general’s office.

Though the social commentary of Breakin’ 2 was important to Firstenberg, he also wanted the feeling of a mainstream Hollywood musical. “We knew that we wanted a bright, happy feeling and look,” says the director.

“There’s a bit of a fairy tale [element] to it,” says Garrity. “There was a desire to make it uplifting, and [the idea] that breakdancing, especially, can solve the problems of the world, or at least the problems of this community.”

Breakin’ 2, like West Side Story (1961), Godspell (1973), The Wiz (1978), Hair (1979), and even The Blues Brothers (1980), relies heavily on highly choreographed dance numbers in practical street locales, an aesthetic that saw its infancy when Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly partially left the soundstage for the streets of New York in the 1949 musical On The Town. Breakin’ 2 is also a non-musical musical—characters don’t break out into song, but they’re constantly dancing to a pop/hip-hop soundtrack – that is on par with Fame (1980), also an unconventional musical, in that the songs and dances are organically integrated into the storyline. Both films feature multiracial casts, urban settings, and large-scale, location-driven dance numbers set to the films’ title songs.

Casa Del Mexicano was painted in dull, neutral tones when the art department first arrived, and it was given a facelift with a rainbow color scheme. “This is what you do when you don’t have a lot of money; you put paint on it,” says Garrity. “You try to uplift it.” (The budget of Breakin’ 2 is estimated at nearly $3 million.) Local graffiti artists were hired, provided supplies, and invited to paint their work on the building’s sides, which garnered respect from the community as a Hollywood production took over this historically significant neighborhood monument.

The film’s finale, the fluorescent-clad Save Our Streets block-party fundraiser, made Casa Del Mexicano’s position at the end of a small cul-de-sac, Calle Pedro Infante, even more appealing. “It really lent itself to being a place for a gathering of a lot of people for this big event. We wouldn’t be stopping traffic except for the people on that little cul-de-sac road,” says Garrity.

Lyons says of Casa Del Mexicano, “That particular location kind of calls out to me in the sense that, why has it not been shot again? Why don’t they put this in everything? … It should have been Police Academy. It should have shown up in whatever throwaway ‘80s movie.” But as a working location professional, Lyons recognizes the property as a logistical nightmare. Moving cars, obtaining permission from the neighbors, and finding space for trailers and trucks in a neighborhood where parking is a high commodity are just a few red flags. Lyons says, “I feel like, at the time of Breakin’ 2, people were like, ‘Yeah, fuck it, let's do it.’ They probably called their friends and were like, ‘Hey, everyone, come hang out,’ and that’s a glorious thing.

Moore has all of his Breakin’ 2 production binders. Two typed pages list all of the residents of Calle Pedro Infante. It’s noted that one resident offered to help the production with parking. At the end of the list, Moore wrote, Let’s all try to be as courteous as possible and treat everyone with respect, as this is their neighborhood we are entering.

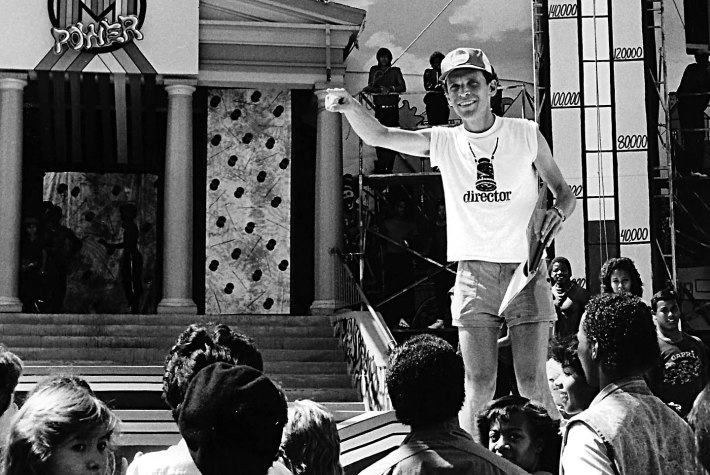

Filming at Casa Del Mexicano took place over a month-long period, and residents of the neighborhood were invited to attend and appear in the audience for the film’s finale. “I remember embracing the people that lived right there on that street. I got to know them really well. On breaks from filming, I’d walk over to people’s front yards and bring them water and sodas and snacks because I felt like they were part of the crew,” says Moore. “I treated them like family.”

This was the case all over Boyle Heights. Moore, who didn’t speak Spanish, often hired neighborhood kids to translate when he needed to connect with location owners. More often than not, they were happy to welcome Breakin’ 2 to their neighborhood. Moore says, “I don’t remember anybody in Boyle Heights being like, ‘We don’t want you here.’ And look, that movie had its fair share of intrusions on the neighborhood. You can tell by just watching it.”

Helping matters was the popularity of Breakin’, which remained in the public consciousness at the time that Moore came knocking for Breakin’ 2. The first film was a huge hit, making over $38 million on an estimated $1 million budget. The sequel was immediately put into production, shot while the 1984 Olympic Games were being played in L.A., and released just seven months after Breakin’. When it came to shooting Breakin’ 2, fans from all over L.A. came out to see “Shabba-Doo” and “Boogaloo Shrimp” film their scenes.

Other Breakin’ 2 locations in Hancock Park and Westwood Village, along with City Hall, strike clear contrasts to Boyle Heights and symbolized the affluent and political forces that the crew at Miracles were fighting against. But nearly half of the film’s running time is centered in Boyle Heights, and those locations were found within a two-mile radius of Casa Del Mexicano. Moore’s notes indicate two additional sites that didn’t appear in the film: Odono’s Meat Co. at Whittier Boulevard and Camulos Street, and a “taco stand” – today Sam’s Tacos – at Soto Street and Rogers Avenue.

Hollenbeck Park appears in multiple scenes, including a couple of high-energy dance numbers inside the park’s bandshell, where Turbo meets his love interest. Chambers says, “As they were doing the big choreography numbers at the Miracles building, somebody jumped in and said, ‘Look, Turbo’s girlfriend Lucia [Sabrina García], she is from East L.A., and what would she be doing? She’s doing cumbias, and she’s doing Latino traditional dance.’ So when I go to Hollenbeck Park, that’s about as real as it gets,” says Chambers. “One thing I like about that scene is that it was a cultural exchange in real-time.”

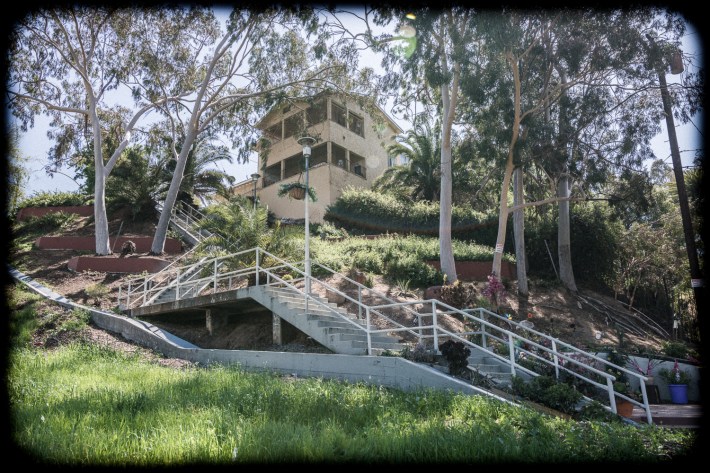

Turbo also takes a tumble down the stairs at Blueberry Hill. The steps were not written into the script, but they were close to Casa Del Mexicano and visually perfect for a plot point that sent Turbo to the hospital.

Moore recalls looking at ten to twenty different streets for the film’s complex opening dance sequence, “Electric Boogaloo.” The highly choreographed scene called for the main cast and scores of dancers and extras to converge upon a residential neighborhood intersection. Moore narrowed the choices to three or four and presented them to Firstenberg, who chose Guirado Street, which slopes down to the west where it meets Orme Avenue.

That stretch of Guirado Street was no stranger to film production. The house where Ozone and Turbo occupy a back garage happens to be Raymond and Chuco’s home from the East L.A. classic Boulevard Nights (1979).

Firstenberg says that the location provided a dynamic range for blocking and camera angles. “What appealed to me was that they would come out of the shack, now they’re on top of the hill, they can dance their way down, all the way to a huge intersection. They would start as a small group at the top; they will end up a huge group at the bottom, and then they’re going to have this dance number,” says Firstenberg. As the cast of dancers grows and descends down the hill, the camera cranes up on an opposite axis to reveal the scope of the gathering. Music playback was blasted over huge speakers that attracted the neighborhood kids, which was personally energizing, says Firstenberg.

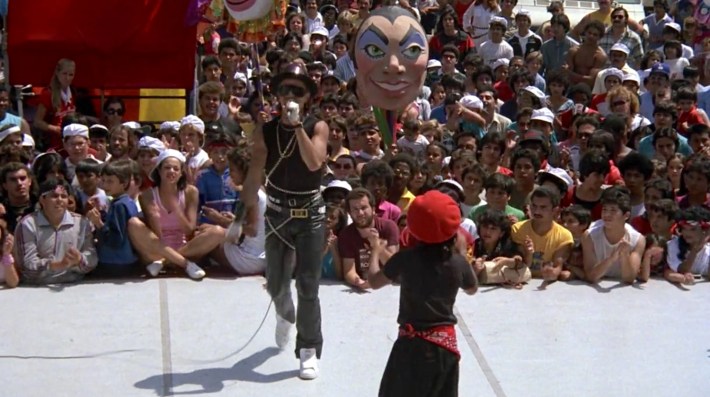

Perhaps the most sweeping and cinematic location featured in Breakin’ 2 is one that has appeared in films like Boulevard Nights, Colors (1988), and Mi Familia (1995). Built in 1928, the 4th and Lorena Street Bridge is the scene of an epic dance battle between Ozone and Turbo’s TKO crew and their rivals, Electro Rock. The confrontation is a little bit The Warriors (1979), a little bit West Side Story. Firstenberg, whose resume is comprised of mostly action films, calls the scene an “action dance.”

“It was a location where there was going to be a confrontation. It would be out of sight of law enforcement,” Garrity says, “It’s that shadowy sort of place with a lot of levels and arches and a place where shit would pile up. It was beautiful at the same time.”

“It’s visually interesting from a human point of view,” says Firstenberg, “and interesting from the point of view that the choreographers will be able to create some more exciting stuff.”

In recent years, Chambers has given private tours of Breakin’ and Breakin’ 2 filming locations to international fans visiting L.A. He is often amazed at the positive impressions these places have left on people. Chambers says, “For them, I think those images were like, ‘Wait a minute, we got Straight Outta Compton, we got Colors, we got all this stuff on the news, and yet this movie in L.A., it was a little utopia where all these people are just dancing and getting along.’”

Firstenberg tells me that upon recording the commentary track for the out-of-print Breakin’/Breakin 2 Blu-ray, he learned that Quiñones was not completely satisfied with the tone of the sequel. “The movie, in his taste, was too happy, too pink-colored to express suffering for a neighborhood or a little community that is oppressed,” says Firstenberg. “He said, ‘I wish it was West Side Story.’” Breakin’ 2 might be a little naïve, but some time later, Firstenberg told Quiñones through email, “You cannot argue with success. Kids around the world like the movie.” Quiñones eventually agreed.

Breakin’ 2 is a pop art fantasy with some documentary sprinkled in. It’s more like West Side Story than Quiñones initially thought and more socially-minded than its neon-fringed poster suggests.

As a sort of an indirect legacy of Breakin’ 2, today Casa Del Mexicano is occupied by the Floricanto Center for the Performing Arts and Danza Floricanto/USA, Southern California’s oldest surviving Mexican folk dance troupe.

Follow Jared on Twitter at @JaredCowan1.