In Born in East L.A., Cheech Marin, playing Eastside native and auto mechanic Rudy Robles, arrives at a toy factory to pick up Javier (Paul Rodriguez), a cousin from Mexico that he doesn’t know. An overhead conveyor line moves stuffed penguins and bears throughout the factory.

“I remember looking at a lot of toy factories,” says Born in East L.A. location manager Dow Griffith. “It’s amazing how secretive they are. If you think that Hollywood doesn’t want their ideas stolen, just try to go into a toy factory. A lot of them wouldn’t even let me scout.” Eventually, Griffith found CalToy, a subsidiary of View-Master, on South Anderson Street in Pico Gardens. The company originally opened in 1959 as California Stuffed Toys, making, among other items, stuffed Disney dolls. It went out of business in 1989.

“They had those real [stuffed] bears that they were making there. So, ooh, how do you make use of this,” Marin tells L.A. Taco.

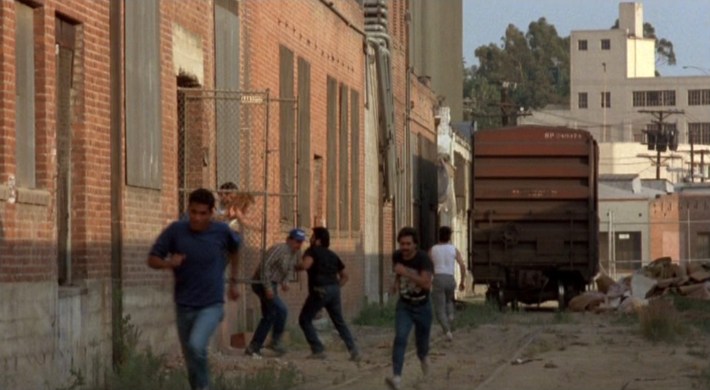

As men and women trim material, tape boxes, and transport crates, Rudy becomes caught in the middle of an immigration raid. The workers scramble throughout the factory; some are able to escape out a rear entrance and bolt down an alleyway, but most are rounded up by immigration agents. The payoff of the scene: Rudy is discovered hiding inside one of the stuffed bears. Having left his wallet and identification at home, Rudy, who speaks little to no Spanish, is deported and forced to spend a few homeless weeks in Tijuana while trying to earn enough money to buy his way back to East L.A. In Tijuana, he discovers a deeper understanding of his culture and the struggles that his people endure to make respectable lives for their families.

The film’s imagery of people scattering at the sight of INS agents, or a line of suspected undocumented workers being led onto a bus outside a factory, is indicative of the photographs of Boris Yaro, the late Los Angeles Times photographer who, in 1968, captured on film a seminal image of Robert F. Kennedy after he was shot in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel.

Born in East L.A., written and directed by Marin, was released on August 21, 1987, less than a year after Ronald Reagan signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act, which cracked down on businesses who hired undocumented workers.

“The raids continued always because of the stop and start nature of the American immigration policy,” Marin tells L.A. TACO. “One day it was this, the next day it was that. They brought in workers when they needed them, and as soon as they didn’t need them, ‘Okay, you can go back now.’”

Among other problems, the 1986 law also failed to address the issue of amnesty for undocumented immigrants who entered the country after January 1, 1982, and many who did qualify were unaware they were eligible due to poor outreach.

Marin takes a jab at Reagan in the toy factory scene by lumping him in with every other white, conservative, movie cowboy of the 1950s. When a macho, lead INS officer (Jan-Michael Vincent)—resembling the former president in a cowboy hat, aviator sunglasses, and a gold belt buckle—asks Rudy, “Who’s the president of the United States,” Rudy responds, “That cowboy guy on TV, uh, the guy that was on Death Valley Days, um, John Wayne.”

Born in East L.A. was based on Marin’s satirical parody of Bruce Springsteen’s 1984 hit—also a critique of American society and U.S. policy. The song was first produced as part of the Cheech and Chong album and mockumentary film Get Out of My Room. Some would argue that Marin’s version of the Springsteen classic is more popular than the original. After the song came out, Marin was told by the Boss himself that when he would perform “Born in the U.S.A. in concert, the audience would often sing “‘Born in East L.A.” “It was like Otis Redding trying to sing ‘Respect’ after Aretha Franklin,” says Marin.

The story behind the song and subsequent film stemmed from a particularly disturbing subset of U.S. immigration policy failure that is still of concern today.

Marin read a story in the L.A. Times about a local kid who got caught in an immigration raid, and he didn’t speak English or Spanish that well. “I think there was some form of autistic spectrum going on,” says Marin, “and he was caught up, and he couldn’t explain himself, and they deported him to Tijuana although he was an American citizen. He was wandering around on the streets of Tijuana for over a month before he contacted anybody. Nobody told his parents where he was; he just disappeared one day.” “Born in the U.S.A.” was playing on the radio at the same time that Marin was reading the story. The idea for the song hit him “in a blinding flash,” he says.

Unlike his character, Marin wasn’t born in East L.A. For the first nine years of his life he grew up around 36th Street and San Pedro Street in South Central, a tough and, at the time, predominately Black neighborhood. In 1955, his dad, an LAPD officer, picked up his family and moved to Granada Hills in the north Valley, a White neighborhood that was surrounded by fragrant orange groves and dotted with glistening swimming pools.

“‘How do I fit in here?’ That was always the question that went back and forth,” says Marin. “But I’m glad I had both experiences.”

Still, he had plenty of Eastside ties.

“My mother was born in East L.A. My father was born downtown L.A., so we had relatives all over all areas, and so I was very familiar with East L.A. growing up,” says Marin. When visiting relatives, Marin found the area to be very family oriented. He quips that better tacos were among his earliest discoveries of the Eastside.

A noted collector of Chicano art, Marin, who in partnership with the Riverside Art Museum and the City of Riverside, recently opened the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, vividly remembers Boyle Heights and East L.A. transforming from a community with a country-like vibe to one of vibrant color through the rise of the Chicano Mural Movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

It wasn’t for lack of familiarity with the area that Marin relied heavily on his location manager, Griffith, during the production of Born in East L.A.; it’s just that he was mostly concerned with story and performance.

“Our process [Cheech and Chong], and then my process, was set up the camera and be funny in front of it,” says Marin.

Marin had previously worked with Griffith on Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie (1980), the follow-up to the comedy duo’s ultra-successful cult classic, Up in Smoke (1978). “If we gave Dow a list of things that I needed when I was directing, he would sit there and nod silently and then disappear. Oh, okay, I guess this is the way they do this in movies,” Marin would think to himself. “Then he would come back and say, ‘Choose one of these for the scene.’ ‘Okay, that one.’ ‘Okay, that’s done.’”

Griffith, however, found Marin “purposeful and directed in his decision making.” Griffith says, “He would spend a lot of time, a lot of days, looking at things, analyzing things, and kind of soaking up the whole environment and realizing what it was all going to look like and feel like.”

Marin also employed the help of his friend—musician, author, songwriter, performance artist, and Chicano activist Rubén Guevara, who first met Marin on Up in Smoke, when he appeared as a member of Cheech and Chong’s backup band. A Boyle Heights native, Guevara is credited as the film’s East L.A. Cultural Attaché. It’s a job title at which Marin laughs, almost uncontrollably, as if the moniker is some kind of inside joke.

“When I needed, like, kind of a… a cultural attaché for the neighborhood…,” Marin says, again cracking up through the mention of it. “‘What’s going on here? Are there places that we should stay out of or any places that would be advantageous for us to go there?’ He would be there. But mostly, we hung out together.”

In our first correspondence with Guevara, he told us he had produced a couple of tunes for the film’s soundtrack, and though he was present on set, he didn’t help choose locations. Guevara later recalled shooting some location scout photos of Lincoln Park and other spots that weren’t used in the film.

“In my mind, Born in East L.A. is the best movie ever made on the subject of immigration by a Chicano or otherwise,” says Guevara.

Prior to Born in East L.A., there hadn’t been many films of note shot in the Eastside—certainly none that spoke to the zeitgeist of Mexican emigration to the United States. Though the majority of Born in East L.A. was set and shot on location in and around Tijuana, the film is bookended and punctuated with Boyle Heights and East L.A. locations that express a dynamic visual character of the area, initiating those familiar with only the often-repeated, archetypal imagery of Los Angeles.

“You saw parts of L.A. that you’ve never seen in a movie before, and that was what made it exotic, especially to people outside of that general area,” says Marin. “People from the Midwest or the East, when they were seeing the film, or other countries, you know, like, ‘Wow, this is part of L.A.? I thought it was just the Sunset Strip.’”

Cheech and Chong’s Next Movie used some Eastside streets, but the film largely takes place in and around Hollywood. Cannon Films’ Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo (1984) was made in Boyle Heights prior to Marin’s film, but the neighborhood is used broadly as an underserved Los Angeles community rather than Boyle Heights-specific. Films like Stand and Deliver (1988), Colors (1988), American Me (1992), Blood In, Blood Out (1993), and My Family (1995) were all released after Born in East L.A.

“I think the only other film before Born in East L.A. [that featured the area] might have been Boulevard Nights (1979),” says Guevara. He theorizes a catch-22: the studios were concerned about filming on gang territory, and producers weren’t interested in telling stories about the community unless it had to do with gangs. Guevara adds, “I mean, a story about immigration? What?” But Marin’s song was a hit, peaking at number 48 on the Billboard Hot 100 in October of 1985. With the music video already under his belt, an offer from Universal to make a feature-length film came shortly thereafter.

Most of the film’s L.A. locations, including the aforementioned toy factory, are seen in the first thirteen minutes of the movie’s 85-minute running time, and a majority of them are technically in Boyle Heights, not East Los Angeles.

“We weren’t really that zeroed in on defining Hollenbeck Park and Boyle Heights and all the communities. To us, East L.A. was everything east of the river,” says Griffith.

The film’s memorable opening title sequence sees a statuesque, redheaded French woman in a green dress (Neith Hunter) debus at the corner of Mateo Street and 6th Street, cross the old Sixth Street Bridge on foot, and make her way through Boyle Heights.

Upon first spying the woman from his pink, 1968 VW Beetle convertible—license plate PINK LUV—at the corner of Chavez Avenue (when it was Brooklyn Avenue) and Fickett Street, Rudy follows her through the area. After losing sight of the woman in Hollenbeck Park, Rudy shouts out to a few dozen people, inquiring about a redheaded girl in a green dress. All of the men, women, and children in the park point in her direction.

At Evergreen Avenue and Wabash Avenue, a man’s sunglasses shatter as the woman walks by; a lowrider’s hydraulics lift into action at the sight of her; a distracted fireman slams on the brakes of a fire engine, sending a fellow fireman soaring through the air. Rudy stops in front of a house on Dundas Street just off of Wabash Avenue, where he asks the people congregated in front—including the flying fireman who’s hanging from a tree—if they’ve seen the woman. Just like the people in Hollenbeck Park, they all point in her direction.

“I wanted to get across that these places exist,” says Marin of the sequence.

“Cheech designed that opening so you could really get a feel for everything,” says Griffith. “He was very creative in that respect, of using locations to really start to formulate the movie.”

The redheaded girl in a green dress eventually appears in front of a mural of Mexican and American flags flying high above a line of classic cars and pickup trucks. As she walks across the street, it’s revealed that she’s arrived at an auto body shop. While she leans up against a car, Rudy slides out from underneath the vehicle in an awkward but somewhat rewarding position.

Marin says, “There was a theory that came out, I swear to God, these guys are working on their Ph.D. in Chicano studies [and wrote about the scene]: it was a French girl, and the French ruled Mexico, so I was trying to say all these three things at the same time. No, the location guy says, ‘Shoot here.’ ‘Ok, great.’ It just cracked me up, and these guys are writing theses for their doctorates.”

The auto body shop was the film’s sole location in East Los Angeles proper. As revealed by the shop’s name and phone number painted on the side of a tow truck parked out front, the scene was shot at what was once Bradshawe Auto, located on the corner of Whittier Boulevard and Bradshawe Avenue.

Tijuana jail scenes were doubled in the Los Angeles Police Museum in Highland Park.

The film’s one recurring L.A. location is Rudy’s house, a five-bedroom home built in 1890 on Chicago Street. Next door is the United Baptist Church of Los Angeles, a Victorian-style church built in 1885.

Marin says that the house wasn’t initially written to be next door to a church; it developed with the discovery of the location. He used it to his advantage by writing a scene in which an altar boy emerges from the side door of the church for a smoke break and lets Rudy’s cousin into the house—but not before trying to sell him some used lottery tickets. It would also make sense that Rudy’s mother (Lupe Ontiveros), a devoted churchgoing woman—proof being her proudly displayed holographic Jesus photo—would feel closer to God living next door to a church. By Marin’s reaction to this observation it’s an analysis on par with the doctorate students’ theses. “I think you could have gone into any house in East L.A. where it had a picture of Jesus in it,” he says, laughing.

The film’s finale perhaps best recreates one of the original images from the music video: Marin emerging from a sewer manhole in the middle of the street. But instead of picking up Elvira on a corner and marching with local residents and business owners, the film ends in the middle of a Cinco de Mayo parade shot along 1st Street between Chicago Street and Breed Street.

“Everybody [in the neighborhood] came out for that,” says Guevara. “There was a lot of excitement.”

Marin recalls a very fast-moving stream of water below him in the sewer. The manhole cover was made with Styrofoam, says the film’s property master, Richard Joffray, who also worked on the music video. “I wish I would have kept the manhole cover because I had East L.A. [printed] on it,” says Joffray.

The parade, complete with marching band and concheros, was staged for the sole purpose of providing an authentic, but comedic, background for the manhole escape. Of filming the scene, Marin says, “There’s this Mexican phrase that goes tanto pedo para cagar aguado. That means, a lot of fart for some watery shit.”

While the scope of the parade is what you might imagine the turnout anywhere that Marin was filming, the exact opposite was true.

“We were never in one place long enough for them [the residents] to get excited,” says Marin, laughing. “You would never know that it was a big studio film if you saw our crew and the amount of people. It could have been an underground, unpermitted film,” he adds. “We were like a guerilla outfit.”

Entirely consumed by what was going on in front of the camera, Marin may not know that, according to Griffith, it’s because of the community’s pride in him that certain locations fell into place. “When you go, and you contact local community groups, gangs, whatever, there’s not a lot of resistance or bad feelings about it because Cheech was really well regarded,” says Griffith.

Guevara remembers that during a break in filming, he and Marin visited one of Boyle Heights’ original Russian-Jewish bathhouses just down the block from Rudy’s house. (It was likely the Schwartz Bath House, built in 1925 next door to Rudy’s house; today, it’s the Los Palomas Apartments.) “We’re sitting there, and we’re talking, and I said, ‘Hey, man, you know, you’re really making a pretty great movie here. It’s getting deep into the culture, especially about immigration. It’s really great that you’re putting a face on the immigrant story. You’re gonna make a mark for yourself.’ Cheech said, ‘Well, I’m just trying to make a good movie, that’s all.’”

Guevara’s compliment feels like the bestowing of an honorary doctorate upon the South Central/Valley boy: Born in East L.A., with all the honors, rights, privileges, and tacos pertaining thereto.

Please keep in mind that some of these locations are on private property. Do not trespass or disturb the owners.

Follow Jared on Twitter at @JaredCowan1.