[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]raffic is stalled on the Century Boulevard ramp going into Los Angeles International Airport on this Tuesday afternoon in September. Luckily, I’m not at LAX to catch a flight as I had been many times over the previous months. I do, however, have an appointment with an airport PR representative that I have to make. And after the traffic cleared — due to a false alarm over a suspicious bag found at a terminal — I made it, parked, met my handler, and was escorted to the TSA checkpoint at Terminal 5 with my Nikon in-hand, experiencing for the first time what it feels like having VIP treatment at a major airport.

There is a sense of familiarity upon this visit, however. Occurring just like it has countless times before, the mystically funky intro of Bobby Womack’s urban hymn, “Across 110th Street,” immediately plays in my head, drowning out the ambient cacophony of the airport as I pass through the x-ray scanner. The 1973 single has been my LAX anthem for twenty years by virtue of Quentin Tarantino’s infallible, audacious caper film, Jackie Brown, which sees Pam Grier as the title character gliding on an airport people mover and taking bold, confident strides to Womack’s euphonious, penetrating beat during the film’s dynamic opening title sequence.

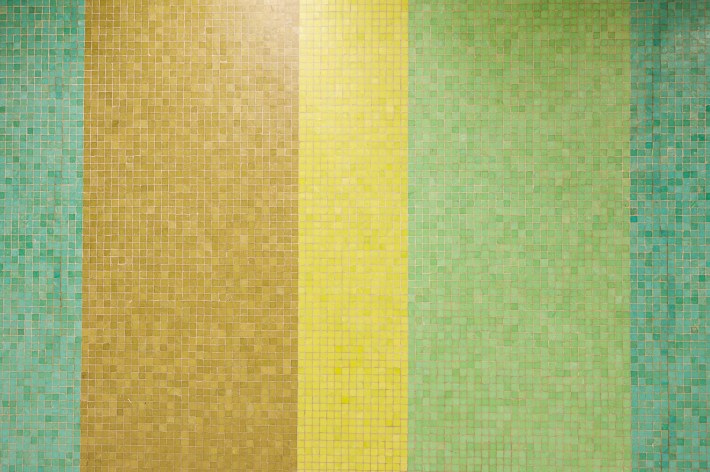

For the 20th anniversary of Jackie Brown, released on Christmas Day 1997, my visit to LAX today is for the sole purpose of walking in the footsteps of Grier. After photographing terminal 5, I am shuttled over to the Tom Bradley International Terminal where Jackie grabs her flight to Cabo. The space today looks hardly anything like it did in ’97. My journey at LAX ends in the place where the film begins: Terminal 3 alongside the iconic minimalist tile mosaic installed at the airport in 1961, which is the setting for one of the most iconic images in Jackie Brown and arguably of 1990s cinema.

LAX is just one of many locations in L.A.’s South Bay region that are featured in Jackie Brown. From a bright and airy beachfront apartment in Hermosa Beach to a timeworn bail bonds office in Carson, Tarantino explores an area of L.A. that is somehow rarely used as a central location for Hollywood productions.

Tarantino grew up in the South Bay and famously worked at Video Archives, a movie rental store in Manhattan Beach, well before he went on to notoriety with Reservoir Dogs (1992), and making it big internationally with Pulp Fiction (1994).

“This was an exploration of Quentin’s childhood in the South Bay,” said Doug Dresser, Jackie Brown assistant location manager, in an interview. “We were able to clearly establish tone and emotion with every location, perfectly.”

The film is perhaps Tarantino’s most fascinating work in that it is his only adaptation to date and yet it blazes off the screen as his most personal movie. The book by author Elmore Leonard, set in South Florida, follows a 44-year-old flight attendant named Jackie Burke who uses her position to bring illegal cash into the country from Jamaica for a small-time gun dealer. Tarantino turned Burke into Brown, a middle-aged African-American flight attendant who works for a bottom-of-the-barrel Mexican airline and lives in the South Bay.

“He already had a lot of these [locations] in his mind,” said Jackie Brown production designer, David Wasco, who, aside from working on Jackie Brown, also designed Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill and Inglorious Basterds for Tarantino.

“It wasn’t, ‘Well, this is an option to use the Del Amo Mall.’ We were using the Del Amo Mall. We were using the Cockatoo Inn,” explained Wasco, adamantly, as we sit in the food court of a completely renovated Del Amo Fashion Center, the film’s main location and referred to in the movie simply as the Del Amo Mall.

“The ‘look’ [of the film] was driven by these interesting places,” Wasco said.

Kyle “Snappy” Oliver, who is credited as a location scout on Jackie Brown, but also coordinated a few of the locations, recalls he was sometimes blown away by the responses he would get when knocking on the doors of potential South Bay locations.

“Oh yeah, Quentin. I used to hang out with him and/or I know him, I’m related to him, or I’m somehow connected to him,” said Oliver, who has gone by “Snappy” since Tarantino bestowed the nickname upon him because of his propensity for dressing nice all the time. (During our interview Oliver is dressed in a dark green suit and short-brimmed fedora.)

When the film was shot in the late 90s, the South Bay was in some ways stuck in a time warp still reminiscent of the 1970s, explained Wasco. Though it’s easy to chalk up Jackie Brown as homage to the Blaxploitation films of the 70s, some starring Grier herself, Wasco and set decorator, Sandy Reynolds-Wasco, say that Tarantino didn’t solely screen iconic titles from the sub-genre, but also films like Ulu Grosbard’s 1978 crime drama Straight Time, as well as some of the earlier movies of Jackie Brown co-star Robert Forster.

‘By putting them on film we have saved them, or captured them, so that for all time you’re going to be able to see what L.A. looked like.’

Where Pulp Fiction captured an eye-popping, vibrant Los Angeles, Jackie Brown was muted and understated. “It captured a certain time; it captured a certain segment of society; it captured almost in some ways a simpler time,” Dresser said of Jackie Brown. “I know that’s crazy [because] it’s about a heist and a murder and money exchanges,” he laughs.

While most of the locations from Jackie Brown are still standing today, the wrecking ball did eventually work its way into the South Bay and, unfortunately, a couple of the film’s most important locations are not around or have been completely remodeled to a point where they are unrecognizable.

Dresser said during our interview, in good humor, that being a location in a Tarantino movie is like a “death sentence.” The warehouse from Reservoir Dogs, and both the diner and apartment building from the opening scenes of Pulp Fiction are among other locations gone today.

I sat down with all these figures at the Del Amo Mall: Wasco, Reynolds-Wasco, and the film’s locations team of Dresser, Oliver, and location manager Robert Earl Craft. We spoke in depth about finding each the places of Tarantino’s tribute to the South Bay and some of the challenges that came with them.

LAX

From the 1980s to the early 2000s, spiking in the 90s, LAX was a hotbed of film activity. Though filming has continued at LAX in the years since 9/11 – IMDb lists mostly reality shows, a few television series, and the occasional feature film – it has no doubt become more difficult to shoot there.

Though Jackie Brown didn’t have to deal with the same types of restrictions or security measures that are in place today, it was intrinsically difficult to shoot at LAX simply because of the logistics of covering so much ground, Wasco said. “We were accessed into places that you would have to build now or shoot at a closed airport.”

A “people mover,” which LAX used to employ in their pedestrian tunnels connecting the terminals to baggage claim areas, was written into the screenplay, but there’s no mention of the tile wall that has become world famous because of Jackie Brown. Regardless, Craft says that Tarantino was well aware of the mosaics.

Technical matters also made the LAX shoot somewhat challenging. In the film, Jackie is seen going in the opposite direction of baggage claim and towards the terminal. Dresser said: “They [the airport] promised us up until two days before that they could switch the direction of it.” Airport engineers, however, were not able to make the required adjustment. After panic set in, a system was devised with the film’s key grip in which dolly system was constructed on the moving walkway. “Pam Grier was sitting on a dolly and that entire shot of her against that mural, going the entire distance, was manually pushed with the camera and Pam Grier sitting there,” said Dresser. “It all came together a day or two before we shot the scene.”

Oliver was tasked with solving another tricky matter at the gate from which Jackie departs in the international terminal. As she collects boarding passes, they were supposed to be inserted into a ticket machine. “That machine wouldn’t take a ticket unless it was an actual flight,” said Oliver, who stayed at the airport the night before shooting, working with a technician on a solution. By morning, the problem was solved, but the ticket machine is never seen in the film.

What you also don’t see in a Steadicam shot at the end of the LAX title sequence are about 450 Japanese tourists and other folks traveling to Tokyo who were stranded because of an engine malfunction on their outgoing aircraft. Dresser said: “We took five PAs that would stand in the middle of the walkway, and as the Steadicam was approaching we would literally take everybody and we would shove them into the gate area. As soon as the camera came by, the crowd would kind of move back.”

Melanie’s Beach Apartment

Though he is said to live at the fictional address of “1436 Florence Boulevard” in Compton, we never see where the film’s charismatic Kangol-wearing gunrunner, Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson), actually lives. Instead, he frequents the houses and apartments of three women he has set up around town as fronts for his illicit business. The one at which he appears to spend the most time is the Hermosa Beach apartment of blonde haired, weed smoking surfer girl, Melanie (Bridget Fonda).

After looking at many different beachfront properties, an apartment in a small, two-level Playa Del Rey building, about 8 miles north of Hermosa, was chosen.

The unit was painted, kitchen cupboards were swapped out, and the furniture was replaced. Reynolds-Wasco said, “You want those other two fellows [Ordell and bank robber Louis Gara, played by Robert De Niro] to be a fish out of water and her character to be kind of unique, so it’s not overly designed, but in its whiteness and its ‘beachiness’ its very feminine and very opposite to these two men that are always on her couch.” It turned out, however, that Tarantino liked this location so much, even down to the actual furniture that was in the apartment upon scouting, which had been replaced with rentals.

Reynolds-Wasco likens the confusion to the fact that Tarantino rehearsed with his actors on the original furniture prior to the shoot day. She said, “I think the angle over Melanie’s leg at De Niro was so important that that chair had to be a certain height, just exactly the way it was in the furniture they practiced in, which was the owner’s.” To remedy the situation, Reynolds-Wasco and her team built up the bottom of the rental furniture to match the shot Tarantino had in mind.

Jackie and Ordell have an exchange of dialogue as they walk out of Melanie’s apartment, down a set of stairs and along an exterior corridor, which didn’t exist at the interior location. “One of the things that is key for Quentin is his words kind of dictate a blocking of how many steps an actor needs to walk to say a line,” said Wasco. In order to save time, a practical decision was made to shoot the scene on a landing at an apartment building next door, which gave Tarantino ample space to block his actors in the time required to deliver the dialogue. Seen along the walkway is a wrought iron S-curve balustrade that Wasco incorporated on the balcony at the interior location in order to tie the two together.

Cherry Bail Bonds

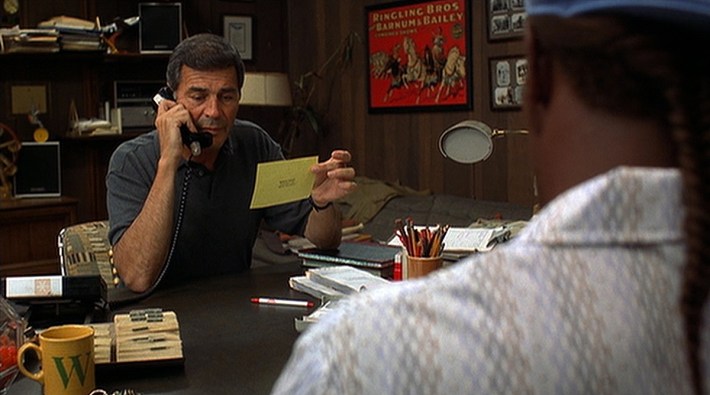

The wood-paneled office of nineteen-year bail bonds veteran Max Cherry (Robert Forster) is set in the South Bay city of Carson and was filmed in a real bail bonds office called, simply, Carson Bail Bonds. The building, across the street from Carson City Hall, is no longer there. In its place stands an apartment complex with street level retail spaces and restaurants.

Dresser told me the owner of Carson Bail Bonds was one of the former mayors of Carson, who owned a couple of bail bonds locations, another of which the filmmakers scouted in San Pedro. But the Carson location was much more appealing. “Cherry Bail Bonds is a guy’s office. It’s not much different than, maybe, the basement office in everyone’s houses in the ‘70s,” said Reynolds-Wasco. “It’s his place.”

In a subliminal, personal touch to the set decorating of Cherry Bail Bonds, Reynolds-Wasco says that Forster supplied the art department with some images of his father who was an elephant trainer for Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Wasco said that incorporating personal items into a scene is a line that he doesn’t traditionally cross. “Quentin actually encouraged us to talk to him,” Wasco told me. “[Forster] did have these ideas and he came with the request to weave into it this Ringling Bros. thing. He wanted to have this ephemera in the background, not that it had anything to do with his character in the movie, but it made him at ease and relaxed.”

Beaumont’s Apartment & Raynelle’s House

Ordell’s “employee,” Beaumont Livingston, played by Chris Tucker in a scene-stealing performance, is shown to live in a rundown apartment complex in Hollywood. Though Tarantino was resolute that a handful of locations appear exactly as they were written in the script, some locations were doubled elsewhere for scheduling purposes, which ultimately led to an easing of pressure on the film’s budget, which, according to IMDb, was estimated at $12 million. Such was the case for Beaumont’s apartment, which was found on Lakme Avenue in Wilmington. The building was ideal because it had the added advantage of an empty lot across the street where Ordell would shoot Beaumont in the trunk of his car. In the screenplay, the apartment building wasn’t necessarily tied together with the lot.

“Often times we have to find things that are close by,” said Oliver. “I had gone to the apartment and looked around and there was this big open field with an oil pump in it and I just thought, How interesting and cool would that be?” The idea turned into a masterful long take that is exemplary of how a location works hand-in-hand with camera movement, blocking, and even sound design.

“It was of the largest signature things I ever had to do. I think we had to get 200 or 300 signatures [from neighbors],” Craft said.

Dresser added, “Because we wanted to do a gunshot in the middle of the night in a residential neighborhood.”

“A tough residential neighborhood,” added Craft.

Making matters more challenging was that the empty lot hosted a working oil derrick, which is clearly visible in the film. “We had to track down the owners of the gas company. They were like, ‘No, we’re not interested in doing gunfire in the middle of our oil field,’” said Dresser as he laughed about the memory. Eventually, after multiple rounds of letters and meetings the filmmakers obtained permission to use the lot.

Around the corner from Beaumont’s apartment on Opp Street, the filmmakers would find the ramshackle house of strung-out Raynelle, another of Ordell’s accomplices. The location was perfect, almost too perfect. “It was a big cleanup and empty-out,” said Wasco. “We had to even flea bomb it. So it was really pretty funky.” Wasco and Reynolds-Wasco brought in actor-safe set dressing, but researched how someone like Raynelle may have lived. Wasco credits, in particular, the photography of Nan Goldin, whose work often showed the effects of drug dependency.

Police Station

Upon retuning to LAX, Jackie is intercepted by Nicolet and LAPD detective Mark Dargus (Michael Bowen). Upon rifling through Jackie’s bag and discovering $50,000 in undeclared cash, they take Jackie in for questioning.

After scouting some possible locations, the idea was brought up that, in an effort to save time and money, the police station could be doubled at the Jackie Brown production office, which was located in a Culver City office space at the intersection of the Marina Freeway and Sepulveda Boulevard. Today, the location is part of Punch Studio, a boutique stationary and home décor company.

“We emptied the producer’s office and everyone else’s offices and redressed it for ATF,” Reynolds-Wasco said.

Attached to the production offices was a warehouse, today filled with palettes of stationary waiting to be shipped out. The filmmakers turned that space into their own mini soundstage where they would bring in a full-size fuselage, construct a police interrogation room and the department store dressing room where the film’s pivotal, multi point-of-view money exchange took place.

Sybil Brand Institute

Sybil Brand Institute was a women’s prison in Monterey Park that operated between 1963 and the year Jackie Brown was released. In fact, the film was the very first movie to shoot at Sybil Brand and the only film to use it as a location while it was simultaneously functioning as a county jail. Today, the prison is still run by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, but it is used primarily for film and television.

Just one of a handful of locations that was not based in the South Bay, Craft said that Sybil Brand was used to add a sense of reality. “If this was a true story and she had been busted, where she was busted for what she was doing, she would have been taken to Sybil Brand,” said Craft.

“There was a smell of fear. When you walked through and it was actually being used … there was a vibe and a fear that came along with that,” added Wasco. “You know, we probably could have recreated it with signage and done it at a place that was a little bit safer, but just the degree of reality it brought was quite wonderful.”

The Cockatoo Inn

“When Quentin would write something, he really wanted to shoot at these actual places. A perfect example is the Cockatoo Inn,” said Dresser.

Opened in the late 1940s on Imperial Highway in Hawthorne, The Cockatoo Inn quickly became a hotbed of Mafia activity and boasted a celebrity clientele; it’s said that President Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe had some of their trysts at the Cockatoo Inn. The hotel bar’s Rat Pack vibe of red Naugahyde booths, dim lighting, mahogany bar, and stained glass windows, all of which you could just make out through a smoky haze, made it a popular spot especially if you were traveling in or out of LAX. By the early 1990s, however, business rapidly declined. The historic landmark subsequently closed and reopened over the next few years under various owners. It eventually closed for good in 1996.

‘I don’t mean I want bars that look like the Cockatoo Inn. I mean I want the Cockatoo Inn.’

After bailing Jackie out of the county prison, Max Cherry suggests the two get a drink. Jackie tells Max there’s a joint close to her apartment: The Cockatoo Inn. With the location permanently shuttered, condemned and fenced off, the locations team researched the Cockatoo Inn and went out to scout other old-school bars that had a similar look and feel. They looked at Dear John’s in Culver City, the Prince in Koreatown, the San Franciscan in Torrance, and the Buggy Whip in Westchester. Dresser told me that upon showing these choices to Tarantino, the director stopped halfway through the presentation. In his best Tarantino voice, Dresser remembered the filmmaker saying, “Um, OK, OK. I don’t know why I’m looking at these because, um, when I write in the script ‘the Cockatoo Inn’ I don’t mean I want bars that look like the Cockatoo Inn. I mean I want the Cockatoo Inn.”

Dresser dug deep by performing various record searches and working with the city manager of Hawthorne. It turned out that a Chinese group had taken over the property and condemned the building because people were living and barbecuing inside the shuttered hotel. Dresser also found out that a family who was related to the hotel’s original proprietors was holding the note of ownership. By sheer coincidence, Dresser had worked with that family previously on a TV show in San Diego. They pointed Dresser back to the city of Hawthorne. “How are we going to get this,” Dresser thought. “How are we going to find out who the real owner of the hotel is? It was in receivership; there was a court appointed trustee. … It was such a complicated web of bureaucracy and paperwork.”

When it seemed as though there was nothing more that could be done, Dresser received a phone call out of the blue that provided a sliver of light at the end of the tunnel. ‘‘Doug? Mayor Larry Guidi, mayor of Hawthorne,” Dresser remembered hearing on the other end of the line. “I understand you have the greatest Italian-American actor working in this motion picture.” Though Dresser wasn’t able to promise anything, the possibility of meeting Robert De Niro was enough incentive for the mayor to pull some strings and open up the Cockatoo Inn.

Upon getting into the building it was discovered that there was no power to be had so an electrician was hired to recharge the electrical system. Wasco remembered thinking that the bar appeared as though the business owners just got up and walked away. He said, “The walk-in refrigerator was filled with food and it was a stench bulb.” Set dressing, though, brought the bar at the Cockatoo Inn back to a trace of its former glory.

With filming having commenced at the Cockatoo Inn after a lot of tooth and nail fighting, the mayor of Hawthorne came to collect his side of the bargain. “I’ve never talked to Robert De Niro in my life up until this point. I go, ‘Excuse me, Mr. De Niro, I’d like to introduce you to…’ and he goes, ‘Wait! Stop!’” said Dresser before pausing. “We’re all just stopped in our tracks and he goes, ‘Call me Bob.’”

Jackie’s Apartment Complex

Just off the 405 Freeway on Yukon Avenue in Torrance, underneath a series of high-tension power lines where electricity can literally be heard crackling overhead, stands a two-story, 48-unit apartment complex built in 1957. Oliver didn’t recall exactly what it was about this apartment building that caught his eye, but he knows for sure that he had a gut reaction upon scouting it for Jackie’s apartment. “It was one of those feelings like hey there’s something about this place that speaks to me,” said Oliver. Only a 20-minute drive to LAX, the location was certainly geographically correct for an apartment of a flight attendant.

By sheer luck, one of the apartments had recently been vacated and “Jackie” could move in. Oliver said that the unit was appealing because it had some depth to it. “You don’t want to just walk into a box. Then there’s nothing you can shoot that looks interesting; you don’t see anything.”

The apartment, originally white in color, was painted in Terracotta and other earth tones for lighting purposes and to compliment the various skin tones that would be photographed in the location. Reynolds-Wasco said that the set dressing was somewhat minimalist to suggest that, as a flight attendant, Jackie wouldn’t have spent too much time at home.

Sam’s Hofbrau

At a screening of Jackie Brown in August at the Ace Hotel Tarantino was asked how the downtown L.A. strip club Sam’s Hofbrau wound up in the movie. He told the audience, simply, that it’s a great strip club. It doesn’t have that much screen time in Jackie Brown, mostly exteriors, though additional scenes were scripted to take place at the location. Tarantino, however, returned to Sam’s Hofbrau a few years later when he used the interior for the My Oh My Club in Kill Bill Vol. 2.

Sometime after Jackie Brown shot at Sam’s Hofbrau, Dresser was contacted about scouting some iconic locations for a Vanity Fair piece about Tarantino that was to be photographed by Annie Leibovitz. Dresser recalled saying to the producers, “I would love to, and that sounds like a great idea. Sure, I’m in for the job, but I can save you some money because there’s only one place that I know you’re going to want to shoot Quentin and that’s Sam’s Hofbrau.”

Upon seeing Dresser’s scout photos of Sam’s, Leibovitz agreed. “It’s pretty legit,” Dresser said of Sam’s. “It’s real. It’s like a strip bar for the warehouse and the industrial workers of Los Angeles, and it has been for awhile.”

Also, located on the 600 block of San Julian Street in downtown L.A., not too far from Sam’s Hofbrau, is the spot where Ordell confronted Louis about losing his money in the bag exchange, which ended in Louis getting shot in the driver seat of Melanie’s VW Microbus.

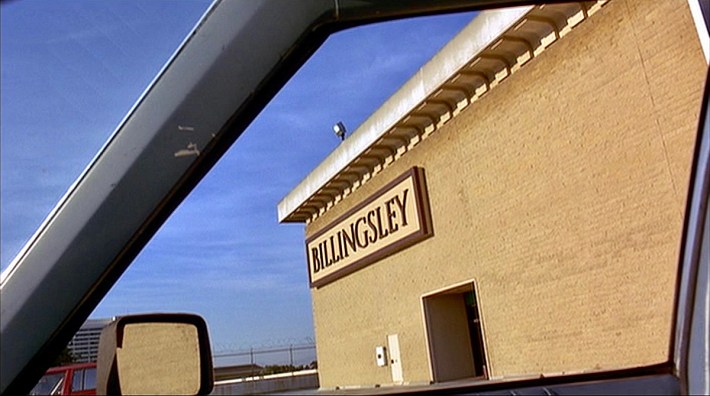

The Del Amo Mall

Touted in the film as the largest indoor mall in the world (in 1997), the ever-expanding Del Amo Mall in Torrance was a central plot device in Jackie Brown. On screen for over thirty minutes of the film’s two-and-a-half hour runtime, the sprawling location of elevators, escalators, and interconnecting thoroughfares and floors created a puzzling, cacophonous atmosphere where all of the film’s main characters converged during a multiple point-of-view bag swap involving $500,000 in cash. Tarantino’s screenplay incorporated numerous areas of the Del Amo Mall including the food court, a department store, a record shop, a movie theater, various parking lots, and common areas.

‘I remember juggling a lot of clothing.’

“As luck would have it,” said Craft, “the son of the Del Amo Mall owner — at the time this was a family-held business — the son of the owner’s girlfriend really liked Quentin Tarantino. So this whole deal rested on getting Quentin to meet him and his girlfriend.” Had this not been the case, the Del Amo Mall probably wouldn’t have appeared in the film, added Craft, frankly. Wasco said that the production also made a deal for Tarantino and the film’s main actors to do Chinese Theatre-style cement handprints. “They were given to the mall,” says Wasco. “My question is where did they go?” (We asked mall management about this, but they weren’t familiar with any cement handprints from the film.)

Though the mall owners were agreeable, there was still a lot of work to accomplish. “Snappy, Bob and I were here for months of prep, months of working with every business and finding every owner and working with the mall management,” said Dresser as we sat in the mall’s new food court. Storeowners had to be paid to come in early to turn their lights on. An ATM machine that was visible in the middle of a 360-degree camera shot had to be moved and supervised by an armed guard. Business names were hidden for clearance purposes, but the filmmakers created some of their own storefronts. At the behest of the director, two fast food chains from the Tarantino universe were added to the food court: Teriyaki Donut from Pulp Fiction and Acuna Boys Authentic Tex-Mex Food, which would later appear in Grindhouse.

After months of negotiations, the biggest mall adjustments happened at Macy’s, which was turned into the fictional department store, Billingsley, where the money exchange scenes took place. “We had to not ever show the name Macy’s,” said Wasco. As a result, the art department created two large Billingsley signs in order to mask signage above the mall and parking lot entrances into the store. Additionally, filming in Macy’s could only take place at night when the store was closed. “We had to go in and take their displays down the minute they closed …and then we had to redress it the next morning before they opened,” said Reynolds-Wasco. “I remember juggling a lot of clothing.”

To save time and money, the filmmakers also doubled an LAX parking structure at the Del Amo Mall. To tie the two locations together, Wasco and his team painted a massive fifty-foot mural that read “International Terminal” and added a wall of mid-century modern brise soleil concrete blocks to match those seen at the LAX Theme Building.

Also near the mall in Torrance was the “Compton” home of Ordell’s other accomplice, that of ‘60s soul music impersonator, Simone.

Today, the Del Amo Mall hardly resembles the version seen in the film. Between 2006 and 2015 the mall was completely renovated and expanded. The food court has been relocated to another section of the mall; Sam Goody, where Max shops for a cassette tape of The Delfonics, closed most of its stores in 2006; American grill Houlihan’s, where Jackie and Nicolet have a steak dinner, no longer exists at the mall. Beige, ceramic tile work was tossed by the wayside in favor of sterile white and grey porcelain walkways; many of the mall’s symmetrical skylights have transformed into curvilinear apertures of light.

Wasco said of the movie’s locations: “By putting them on film we have saved them, or captured them, so that for all time you’re going to be able to see what L.A. looked like.” Though the South Bay may have changed over the past twenty years, Tarantino’s Jackie Brown is a permanent testament to an important time and place where one of our most celebrated filmmakers was doing his most personal work.

Please keep in mind that some of these locations are on private property. Do not trespass or disturb the owners.