It’s a scorching hot Tuesday afternoon in Huntington Park, and a stalled-out Toyota Prius is blocking the middle of a strip mall parking lot that may be home to one of the best fried chicken dishes in California.

“I’ll help you,” a Honduras Kitchen manager yells in Spanish to the obviously embarrassed driver of the Prius.

Me and my nephew quickly join, only to discover you can’t really push a dead 2007 Prius no matter how many leg days you’ve banked—because there is no easy way to put it in neutral.

No matter. It’s the kind of moment—a restaurateur dropping everything to help a member of the community—that Honduras’ Kitchen has become known for these days.

Back when it first opened in the early 90s, it was known for its sopa de caracol, which the late great Jonathan Gold described as “a shrine to the mighty Caribbean mollusk caracol, a Caribbean mollusk that is culinarily, if not biologically, identical to the Italian scungilli and the Florida conch . . . though the word caracol translates literally as ‘snail.’”

Back then, Honduras Kitchen was a small, tightly packed mom-and-pop spot where Gold dined on dishes made by Maritza Larios, who founded the restaurant with her husband, Rafael. Today, the space is larger, sleeker, and run by their son, Jonathan, who has modernized the operation while staying fiercely loyal to its roots. His brother runs their second location in Long Beach.

“You could say I’m second generation now. It’s more modernized—it has more of a Panera/Chick-fil-A concept when you order up front,” Larios tells me. “But it wasn’t always like that. It was a different mom-and-pop concept. We’re the oldest Honduran restaurant in California—33 years old now.”

It’s my first time inside Honduras’ Kitchen, but not my first time tasting its soul. I first encountered their baleadas—pillowy flour tortillas folded around silky refried red beans, a tangy dollop of mantequilla, and a snowfall of salty, crumbled cheese—outside La Cita, served from a pop-up that drew a long, hungry line.

My guide that night was La Cita’s headline act, Suanny, a rising Honduran musician and friend, who insisted I couldn’t call myself an L.A. food lover until I’d tasted a proper baleada. She was right.

“Every challenge, there’s something positive you can grow from,” he says. “We’ve been through tough times before, and we always find a way. You just take that first step and keep going.”

A framed copy of Gold’s 1994 review of the restaurant is one of the first things that greeted me when I entered the iconic Honduran eatery this past Tuesday. Because I can’t resist, I read a bit of Gold’s take.

“The restaurant serves caracoles fried in crisp batter, doused with citrus and grilled until they resemble a sort of veal piccata of the sea. They also come raw in spicy cocktails and boiled in the restaurant’s famous soup. At Sunday lunch, over the blare of salsa music, over the din of conversation and wailing babies, is the thwack-thwack-thwack-thwack of somebody in the kitchen pounding caracoles to chewy, abalone-like tenderness.”

Like J. Gold’s culinary prose, the food at Honduras’ Kitchen still slaps—like a good punta track pulsing through a crowded dance floor at La Cita. Their pollo chuco, a crown jewel of Honduran street fare, arrives glistening—legs and thighs fried to a shattering crisp, yet impossibly juicy within, as if the meat has been seasoned not just with salt and citrus but with the essence of ancient Maya itself. A tangle of curtido cabbage slaw adorns the dish, cool and vinegary, cutting through the richness like a syncopated drumbeat. The chicken is drizzled with salsita (Honduran dressing) and rests on a bed of golden fried green plantains that manage to be both sturdy and sweet, absorbing just enough of the house tomato sauce—silky, sun-warmed, and spiced like a family secret.

“That sauce is my mom’s recipe,” Larios says with pride. “You can’t have the dish without it—it ties everything together.”

Honduras’ Kitchen is the kind of place where you don’t just eat food—you experience the kind of culinary masterpieces your grandma made when you got home from school. “It’s one of my favorites,” Suanny, who grew up in South Gate, tells me over text. “It’s my childhood staple.”

According to Larios, that’s the case for a large part of Southern California’s Honduran community. But lately, the vibe has shifted.

“It’s worse than COVID,” Larios says, explaining the chilling effect that recent ICE raids have had on his business and the surrounding neighborhood. “People aren’t just broke—they’re scared. They’re not even trying to come out anymore.”

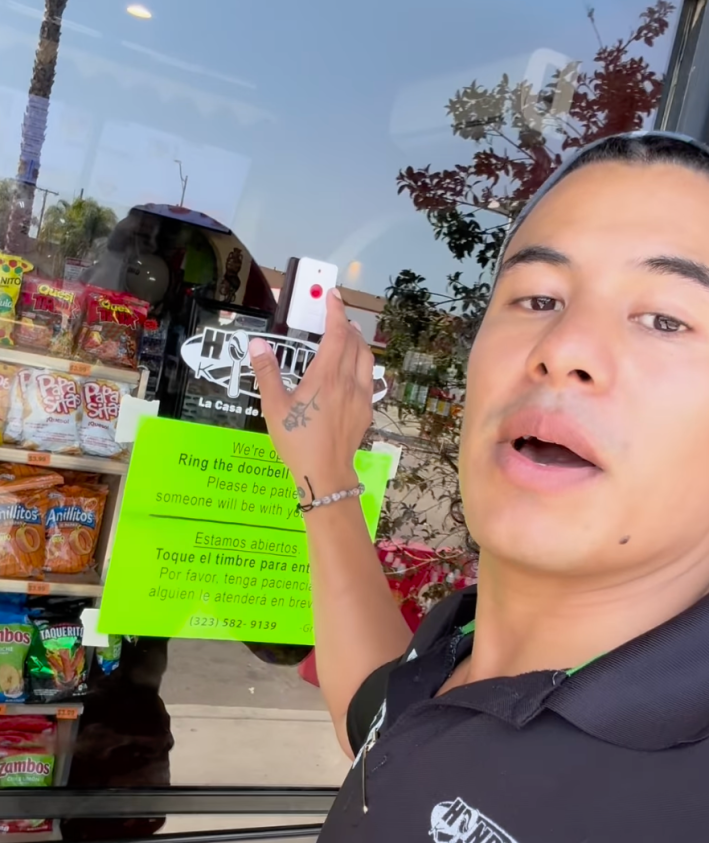

In response, Larios installed a buzzer system at the front door, locking it during open hours. Customers now have to ring to be let in.

“It gives a sense of confidence,” he says. “It protects my employees and makes our people feel safe.”

The video he posted explaining the change went viral on TikTok and Instagram, bringing in a wave of curious new customers. But the underlying fear lingers. Just across the street from their sister location in Long Beach, ICE agents recently hit a nearby bike shop.

“It’s not just us. It’s Los Angeles. This city runs off immigrants,” he says. “They’re targeting our people. That’s what’s so hard.”

And yet, through it all, Larios remains relentlessly hopeful.

“Every challenge, there’s something positive you can grow from,” he says. “We’ve been through tough times before, and we always find a way. You just take that first step and keep going.”

During COVID, he turned the empty dining room into a donation hub and clothing center, collecting mountains of food and clothes for people affected not just locally but back in Honduras, where two hurricanes struck in quick succession. The move got the attention of the Honduran vice president at the time Salvador Nasralla who visited Honduras’ Kitchen for a 30th anniversary celebration. But Larios is quick to point out it wasn’t about impressing politicians, it was about doing something for those in need.

“We did it because I saw my parents do it during Hurricane Mitch,” he says. “That’s the blueprint—we help each other.”

The restaurant itself has gone through several lives. In the early 2000s, it doubled as a nightlife venue where reggaetón and punta music blasted until 2 a.m., and musical icons like Ivy Queen, and Joan Sebastian passed through its doors. Larios, who grew up in the restaurant, recalls fighting drunk customers as a kid and sleeping through first period at school. Eventually, he phased out the nightclub and leaned into a new concept: part counter-service restaurant, part bodega.

The store now sells nostalgic Honduran staples—coconut milk, soaps, cereals, cheeses, and homemade salsas—as well as shirts, chips, and, soon, produce like tomatoes and avocados.

“If I can’t get people to come eat three times a week, maybe they’ll come for groceries,” he says.

He’s even planning to open a coffee shop inside the space, serving only Honduran beans.

He knows the restaurant’s survival depends on more than great food, though. It depends on community.

“There’s always a way forward,” he says. “But it starts with being visible, even when it’s scary.”

Tonight, Honduras plays Mexico, and Larios hopes the restaurant will be full. He used to pull out extra tables on game nights. He’s not sure if he’ll need them now.

“People used to come out for the culture,” he says. “We’ll see if they still will.”

I’m not a fortune teller, but I do know that Los Angeles County has been a bit better since Honduras’ Kitchen opened its doors in September 1992. And the fried chicken is worth the drive—even if your car breaks down in the parking lot. Don’t worry. Someone—more than likely a Latino—will help.