L.A. TACO is on its biggest mission yet: to create a taco guide for every single neighborhood in Los Angeles! Along the way, we will also be releasing brief histories of each neighborhood to understand L.A. a little more and celebrate how each and every neighborhood makes our fine city the best in the world.

The Historic South-Central neighborhood we think of today was established when African Americans began moving into the area in the late 19th century and early 20th century around the land holdings of Biddy Mason, a nurse, philanthropist, and businesswoman, who was born a slave in South Carolina to later become one of the first Black women to own real estate in L.A.

African American populations boomed along Central Avenue in the first half of the 20th century, often because of the racially restrictive housing rules that kept them from owning or renting in other parts of the city. The community continued to grow as large migrations of people from Texas, and other parts of the U.S. South arrived to fill defense industry jobs during our nation’s involvement in World War II.

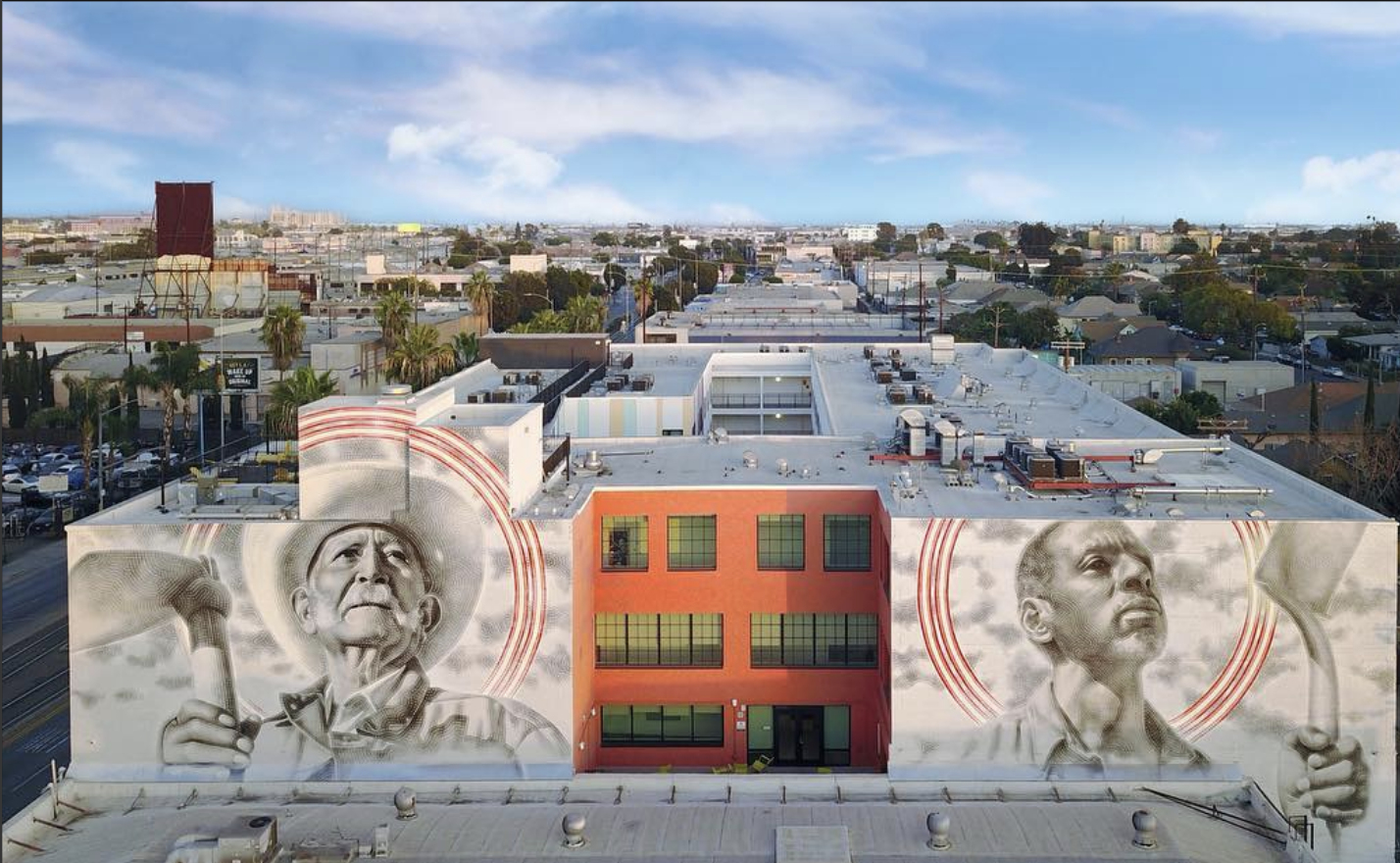

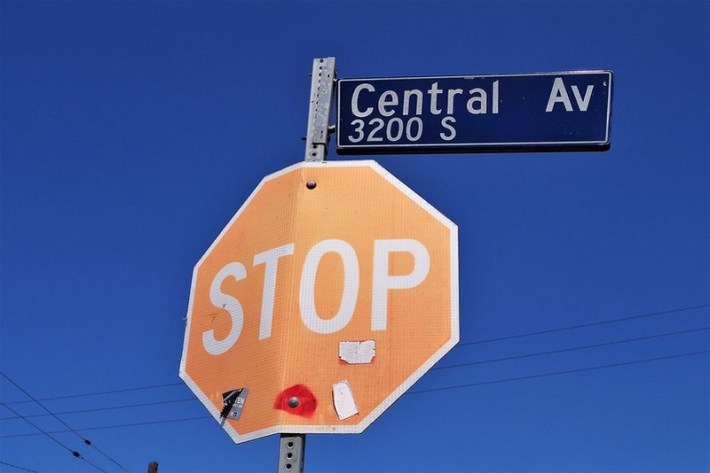

The name “South-Central” was initially applied to the rectangular parcel of the Central Avenue corridor as it runs to Vernon Avenue from Washington Boulevard. Today, “Historic South-Central" encompasses the area between the Harbor Freeway on the west, Central Avenue on the east, Washington Boulevard to the north, and Vernon Avenue to the south. However, the name “South-Central” continues to be used erroneously by many in L.A.—whether through redundancy or reductivity—as an all-encompassing misnomer for much of South Los Angeles and that region’s historically Black residential and commercial areas, incorrectly including neighborhoods such as Watts, Compton, Inglewood, Baldwin Hills, and Crenshaw.

Central Avenue was the epicenter of Black cultural L.A. life from the 1920s to 1950s. During this time, jazz and R&B nightclubs dotted the street, including the legendary Lincoln Theater, sometimes referred to as the “West Coast Apollo,” as well as famous names like the after-hours Jack’s Basket Room, Club Alabam, Club Congo, Ivie’s Chicken Shack, and Dolphin’s Record Store. The music scene provided a rich and supportive culture for local musicians--including Watts-raised Charles Mingus--to study, network, and perform, as well as to welcome visiting greats, including Charlie Parker, Lionel Hampton (who recorded a song called “Central Avenue Breakdown”), Big Joe Turner, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Johnny Otis, Louis Armstrong, and Dinah Washington, who performed at the seminal “Cavalcade of Jazz” festivals, which were held for 13 years at the neighborhood’s Wrigley Field.

Given the restrictions of segregation, visiting stars would often stay at The Dunbar Hotel at 43rd and Central. Nearby, Jefferson High School was an important incubator for homegrown musical talent, with a dedicated curriculum that would help nurture the talents of local luminaries such as Etta James and saxophonist "Big" Jay McNeely. While Central Avenue in the 30s was sometimes referred to as “Little Harlem” due to the Black American arts and culture renaissance happening along the street, contemporary jazz great Wynton Marsalis once said, "Central Avenue was the 52nd Street of Los Angeles," for its profusion of jazz venues that mirrored a small stretch of Midtown New York’s. Today, The Central Avenue Jazz Festival is held here every July.

Central Avenue and its surrounding streets were pivotal to Black life and the struggle for equality and justice in the divided, racist L.A. of that time. The Second Baptist Church, found at 24th and Griffith is one of the city's Historic-Cultural Monuments, starting as a small second-story room and growing in 1926 to the Paul R. Williams-designed Romanesque Revival building that seats 2,000 that we see today. Nearby, Liberty Savings and Loan Association was the first African American-owned business of its kind opened west of the Rockies, noted for helping Black entrepreneurs establish their businesses. The 28th Street YMCA offered a state-of-the-art clubhouse and swimming pools in a time of widespread segregation. Fire Station No. 14 was the city’s second all-Black fire station, established in 1936. The progressive California Eagle newspaper was owned and overseen by Charlotta Spears—the first African American woman to do so--and committed to fighting for the rights of African Americans, women, and unions.

Nobel Prize-winning United Nations diplomat, scholar, and human rights activist Ralph J. Bunche grew up at 40th and Central, while one block down, the L.A. chapter of the Black Panthers was organized—the first outside of Oakland—by Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter, a former Soledad inmate and Slausons street gang member who was influenced by conversations with Panthers founder Huey Newton. The chapter provided free meals for children, in addition to studying politics, first aid, firearms, and the tenants of Black liberation, growing by an estimated 50-100 members weekly, and including prominent Panthers such as Geronimo Pratt and Elaine Brown.

Less than two years after being established, the building would be swarmed in December 1969 by L.A. police, who worked with the FBI to harass and intimidate members through numerous documented incidences of false arrests and warrant-less searches, resulting in a shootout. Carter himself was shot and killed amid an argument during a meeting of the Black Student Union at UCLA's Campbell Hall at the start of that year. This typical type of aggressive, violent, and racist policing, under the leadership of police chief William Parker, is sometimes cited as the reason for Central Avenue’s initial decline, as the row’s thriving, music-centered businesses were pestered, maligned, and hounded through the 1950s and early sixties, boiling over into the Watts Rebellion of 1965.

Neighborhood-obliterating freeway construction, police terror, the closing of industrial plants and resulting job losses, Reagan-era divestment in social and cultural programs, crack cocaine, and the rise of violent street gangs collaborated to produce an observable decline of Central Avenue in the 1980s. Conversely, the decade began a rise in the number of Latino households and residents in South L.A., which grew 200% between 1980-1990, and today comprises a majority of the neighborhood and region’s residents.

Like many other neighborhoods, a new generation of both native and transplant young Angelenos are purchasing homes, adding to Historic South-Central's diverse history.