The intersection of Lombardy Boulevard and Eastern Avenue in El Sereno doesn’t look like much. Farmdale Elementary's faded murals are on one side, as a car wash bustles across the street. On the opposite corner, an empty lot fronts a weed-covered, dried-out hillside.

But look a little closer next time you’re stuck at a red light here. Better yet, pull to the side of the road and walk around. You’ll notice something happening in that little lot.

Southern California black walnut sprouts stretch towards the sun amidst splashes of blossoming white sage and purple sage, speckled among the familiar oranges of our state poppy, and the pale pink shades of of narrowleaf milkweed.

You’ve found the Eastern/Lombardy Guerilla Garden, one of many environmental conservation efforts currently taking place around this tiny neighborhood, nestled into the hills on Los Angeles’ eastern fringes. This was once ‘Ochuunga, one of the original Tongva villages before Spanish colonization.

“We saw this dirt lot with a bunch of weeds,” said Micah Haserjian, a co-founder of Coyotl + Macehualli, the organization behind the garden’s planting. “This is a city plot, so we were like, we should just plant a native garden here and activate this space. We start organizing here and showing people what this could be.”

Coyotl + Macehualli is just one of numerous organizations working within El Sereno that view environmental conservation as a way of fighting for housing security, land reclamation, and climate justice. Local activists are hoping to prevent the over-development, gentrification, and displacement that has affected so much of the city's Eastside and Northeast neighborhoods by prioritizing green spaces and community ownership, and creating space for the natural heritage of the neighborhood.

Projects such as Coyotl + Macehualli, Save Elephant Hill, Elephant Hill Test Plot, and the El Sereno Community Land Trust are all working to ensure that both wildlife and demographic diversity are not sacrificed in the name of urban development. Their work can be seen in pockets throughout the neighborhood, from guerilla planting events in Elephant Hill to black walnut monitoring in the hillsides to community-owned apartments and the Ooxor ‘Aweeshko Garden on Wadena Street.

El Sereno is far from the only neighborhood in L.A. where environmental activism is taking place. Still, the sheer amount of local organizing in the face of growing interest from land developers make it a unique test case.

Local organizers agree that El Sereno is on a precipice, with myriad possible futures. As such, the work its activists are doing in this often-overlooked community could function as a model for neighborhoods throughout the city hoping to prioritize environmental conservation and sustainable growth.

“This happens all the time, this is the mindset developers have, this sense of entitlement: I purchased this land. It belongs to me... "

“In an ideal world, we wouldn’t be doing this work,” said Brenda Contreras, co-founder of Coyotl + Macehualli [with Haserjian, her partner]. “We’d be existing with nature and supporting nature, but there are a lot of challenges we’re facing right now with housing security, land speculation, climate change. A lot of these problems stem from colonization, patriarchy, white supremacist values.”

Like many environmental groups, Coyotl+Macehualli started with a lawsuit. The group was formed in 2019 in response to a proposed development on Moffat Street, located on the border of El Sereno and South Pasadena.

“We were told it was a matter-of-fact project,” Contreras said. “This happens all the time. This is the mindset developers have, this sense of entitlement: 'I purchased this land. It belongs to me.' We challenged it. We kept on challenging it until it turned into a lawsuit. The lawsuit required us to have a nonprofit, and we continued this because it’s not just one hill.”

They have since been involved in two additional lawsuits, including one ending in a recent victory to protect the hillside behind the guerilla garden. Most lawsuits end with settlements, but Coyotl+Macehualli said they do not want traditional financial agreements.

“We aren't interested in settling,” Contreras said. "We are interested in preserving.”

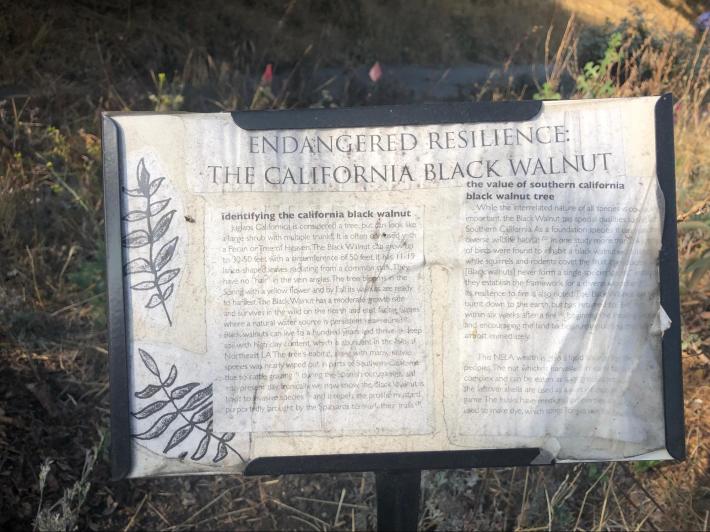

The tree at the center of their efforts is the Southern California black walnut, a tree indigenous to the land, uniquely common on El Sereno's hillsides, and considered threatened by the California Native Plant Society. The tree is even the focus of a now-annual Black Walnut Day (the inaugural event was attended by more than 500 people last September).

“Southern California black walnut has been at the center of a lot of the lawsuits,” Contreras said. “It’s emblematic and mirrors the threats of displacement in our community. These trees are being displaced, and the people are being displaced. Seeing the land be healed is super healing and something our community needs.”

Coyotl+Macehualli, which are Nahuatl for “coyote” and “indigenous person,” in order to symbolize the connection between land and its people, sees the impact of land conservation as reaching far beyond simply creating more shade.

“Decolonization is one of the things that resides in our values,” Contreras said. “Building the relationship with the land. Holding the city accountable. Continuing with the healing and decolonization. These are all intersectional issues, because it does affect the stability of housing, of people's mental health.”

Much like the problems they address, conservation efforts in El Sereno are deeply interconnected - organizations collaborate frequently, and it’s common to see different members at one another’s events - but if there is one person who ties them all together, it is Elva Yañez.

Yañez founded Save Elephant Hill in 2003 in response to a developer’s plans to build luxury homes on the plot of the 110-acre Elephant Hill it owned, known as “The Heavens” to locals. After a six-year fight, filled with coalition building, on-the-fly legal training, and the discovery of multiple legal violations on the part of the developer, Save Elephant Hill and their partners eventually stopped the development.

“The victory we had back in the early 2000s was groundbreaking for me personally,” said Yañez, who lives along Collis Avenue at the base of Elephant Hill. “It told me that we can do this, if we can stop a developer represented by the best land use attorney in Los Angeles, then we can do anything.”

As part of the 2009 settlement, the city acquired 20 acres of Elephant Hill as public land. The rest of the hill remains parceled between 300 separate owners.

Yañez said the efforts of Save Elephant Hill helped provide a template for the newer conservation efforts currently taking place in El Sereno.

“What we did was demonstrate the possibilities,” Yañez said. “If you invest the resources, time, and effort, primarily in people and the community, you can make change.”

Under-investment of resources, said Yañez, is one of the reasons why the fight to save Elephant Hill was necessary in the first place. It’s one of the reasons why, even though the legal battle is over, she continues fighting for the hill, which has become a dumping ground for refuse as well as a popular, and dangerous, site for off-roading.

“We don’t have a lot of social infrastructure in El Sereno,” she said. “The things that take place on Elephant Hill wouldn’t happen on the Westside. That’s because of who has historically lived here.”

El Sereno, Yañez said, was known as a place for affordable housing for working class people. The predominantly Latino community was long neglected and their land exploited. She said that has changed over the years, both as local activist groups organize and the demographics of the community change.

In the years since founding Save Elephant Hill, Yañez has seen development and displacement across El Sereno as gentrification in neighboring Highland Park spilled across the hill, and homes on Collis Avenue began routinely selling for over $1 million.

The problem, she said, is not necessarily the new people moving into the community. It’s the systemic factors that lead to a lack of affordable housing and high housing costs in the first place.

“The way the system is set up is for developers to dominate,” she said. “The little guy, the regular person who doesn't know about how the system works, land use planning happens to you, not with you. It’s the invisible force that determines so much about where we live. It’s like air pollution: you can’t see it, but it will have an impact.”

Yañez said she believes the current generation of environmental activists has an intuitive understanding of the systemic forces at play and the increasingly dire effects of climate change.

“There’s this deep understanding that we are in a horrible situation,” she said, “and if we don’t do something about it, we’ll be in dire straits.”

Efforts to “do something about it” surround Elephant Hill, which has become a hub around which conservation groups orbit. Anahuacalmecac International University Preparatory of North America recently acquired 12 acres of land on a hilltop across Collis Avenue and plan to cultivate native plants on the land they now steward.

Heroes of Elephant Hill is a network of volunteers who help clear trash from The Heavens. The El Sereno Community Land Trust helped launch the Ooxor ‘Aweeshko Garden off of Wadena St. and is involved in multiple community-owned land projects around El Sereno. Organizations such as Anahuacalmecac and Coyotl+Macehualli are also actively involved in the land return movement, working with organizations such as the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy to return land to the Tongva people who originally inhabited it.

One of the most recent efforts to continue the work on Elephant Hill is the El Sereno Test Plot, a 5,000-square-foot tract of public land that is gradually being converted into a native garden and community space.

“A lot of this is about access and activating the hill so people feel comfortable to spend time here and have access to nature as they have in other parts of the city,” said Joey Farewell, the Test Plot’s land steward who first proposed the idea shortly after moving to El Sereno in 2020.

“I’ve hiked every corner of the EH property with my toddler on my back and soon realized this is an amazing place,” Farewell said.

Farewell approached Jen Toy, an architecture professor at USC who leads Test Plot, which oversees eight sites around the city. After gaining her enthusiastic approval for cultivating a space on Elephant Hill, he spoke with many community members, including Yañez, who has become something of an unofficial advisor for the Test Plot.

“This property was purchased so folks of color, Latino communities, blue-collar communities can have access to nature in their backyards, and they don’t get pushed out by a bunch of McMansions,” Farewell said. “It’s one thing to buy the property and to preserve it, but you also have to activate it."

The Test Plot has activated the land in a variety of ways. Last summer, more than 70 volunteers helped clear the land and planted more than 200 native plants, most of which are now flourishing.

Students from El Rio Elementary School recently visited the Test Plot for an after school field trip and helped place markers at the many black walnuts sprouting throughout the land. Farewell said the next step is to increase community awareness and access.

“Let’s go door to door,” he said. “Let's make sure folks know what this is, know that this is their space - it doesn’t belong to Test Plot. Ultimately, this is public land, this is their land. This property was bought so folks in El Sereno would have access to nature.”

The contrast between the Test Plot and its surroundings on the hill is striking. The Test Plot is vibrant, bursting with greens, the playful oranges of monkeyflowers, and the hard work of busy bumblebees and monarch butterflies. It is surrounded by thickets of 10-foot tall, desiccated, and withering black mustard plants, giving the impression of a dusty tinderbox.

“The vision for Elephant Hill, the vision for this, it’s all connected,” Farewell said. “Elephant Hill as a highly accessible, safe, public space and nature space for Latino Folks, folks of color, working class folks to have the same access to nature that folks in Glendale, in Pasadena, have. On an ecological level, we want to make sure the trees are growing, that they're creating shade, a space for people to sit under.”

Though Farewell is relatively new to the neighborhood, he said he believes the rise of conservation organizations around El Sereno is directly tied to the community’s history.

“You have the open spaces, some of which are protected but many of which are not, you have a culture and shared community of history and appreciation for these spaces of folks hiking and making memories in these places, and that’s a beautiful thing,” he said. “You also have pressures and threats of gentrification and development and displacement, and that has really lit a fire under folks. These groups recognize that these hills and these spaces and this habitat are special, they’re threatened, and a wave of McMansions will wash over these hills if folks don’t advocate.”

Contreras of Coyotl+Macehualli said El Sereno’s unique geography has also helped protect it from development.

"A lot of us have relationships with those hills that are being saved. They’re our roots, our connection to our home. That connection to the land and connection to home is something we all long for and try to hold onto."

“For a long time it wasn’t profitable to develop on some of these steeper hills,” she said, “and it allowed for these sites to be spared from development in an unintentional way. They’ve become stepping stones. There’s a huge opportunity. We really need to conserve. That’s top priority. Conserve what we have, invest in green architecture. Continue to plant native species.”

Advocacy, Farewell said, is important in order to ensure there is still land to pass on to another generation.

“It’s important for the younger generation to know that these places are theirs,” he said. “These places have been fought for, they are being fought for, and they can carry on that stewardship.”

John Urquiza, a community organizer and member of Coyotl + Macehualli, said that he sees the fight to preserve the environment in El Sereno as a deeply personal one.

“I grew up in El Sereno,” he said. “I have a relationship with those hills, with Ascott Hills. As a kid, I would run around up there, playing soldier guy. My older brothers learned how to drive up on those hills before they had fences. A lot of us have relationships with those hills that are being saved. They’re our roots, our connection to our home. That connection to the land and connection to home is something we all long for and try to hold onto. As *ucked up as gentrification is, we don’t know we’re fighting it sometimes.”

Elva Yañez, who founded Save Elephant Hill when there were no other local environmental organizations and has remained committed to the cause for over two decades, has a simple, hard-fought lesson to pass forward, telling us:

“When you stop the bad things from happening, then good stuff can happen.”