Welcome back to L.A. Taco’s column, “Barrio Wisdom.” In this series, we follow the streets-meet-academia wisdom of Dr. Álvaro Huerta, a professor at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. In this installment, we learn how the Mexican way of life in El Norte has many things in common with the current restrictions amid the coronavirus pandemic crisis.

[dropcap size=big]D[/dropcap]uring this pandemic coronavirus (COVID-19) in the U.S. (and beyond), it behooves Americans to learn from Mexican Americans or Chicanas/os (not that we’re not Americans) and Mexican immigrants about the art of survival in a time of crisis.

Mexicans, on both sides of la frontera (too preoccupied to translate), have experienced a constant state of crisis caused by the American state and a significant segment of its white citizenry since the early 1800s. More specifically, since the Yankees stole Texas (1836) and Southwestern states (1848) from Mexico, mi gente has been surviving under tumultuous, precarious and uncertain conditions. There’s a famous saying in Mexico which reinforces my claim: "Pobre México. Tan lejos de Dios, tan cerca de los Estados Unidos." Nowadays, it is the crisis of regional narco-violence as drug lords fight to be America’s main supplier of amphetamines and opioids.

Being family-oriented, Mexican descendants in el norte commonly rely (socially, economically, spiritually, etc.) on their family members (immediate and extended) on a regular basis. This includes what anthropologists refer to as fictive family members, like compadres, comadres, padrinos, madrinas, etc. Through these interpersonal ties or strong sociological ties (see Mark Granovetter), we support each other with housing, food, babysitting, job referrals, money-lending, rotating credit associations (tandas or cundinas), etc. (This includes toilet paper!)

During my youth, when I visited my grandparents in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico, or cousins in La Puente and El Monte, Alta California, U.S., I always (to the present) felt at home. Apart from being served delicious Mexican food, whether hungry or not, I could always get more tortillas and open the refrigerator without permission. (In Mexican households, there are no labeled items in the refrigerator, like “Brad’s milk or Tiffany’s kale!) I could also stay over for extended periods of time, if in need.

"Pobre México. Tan lejos de Dios, tan cerca de los Estados Unidos."

In terms of food, I’ve noticed that Americans have been pillaging Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods, etc. like there’s no tomorrow. But the tienditas and carnicerias that have fed millions of Latinos from Mexico and Central America are still going strong, keeping most of their shelves full of essentials like rice, beans, meats, and produce. They have and will continue to feed their respective marginalized communities.

During the global depression of the 1930s through the 1950s, living in a small rancho (Zajo Grande) in the beautiful Mexican state of Michoacán, my parents and family members survived on basic Mexican staples, like maíz and frijoles. Making and consuming tortillas hechas a mano de maíz is common in the rancho. (I’m sure there was much more variety in their daily diet, like queso, chile, avocados, nopales, etc., which I need to investigate further with my older relatives from Zajo.) They didn’t consume meat and poultry regularly until they migrated to el norte.

Despite the powerful forces of assimilation and acculturation in this country, if necessary, Mexicans in el norte (First, second, third, fourth generations, etc.) will simply fall back to the healthy culinary ways of their ancestors. It’s time to rely on the time-honored nutrition of rice and beans with the occasional bit of dairy, eggs, and meat to get you by. If those powerful ingredients fueled entire generations of people in the Americas, it will get us through these times too.

Being family-oriented, Mexican descendants in el norte commonly rely (socially, economically, spiritually, etc.) on their family members (immediate and extended) on a regular basis.

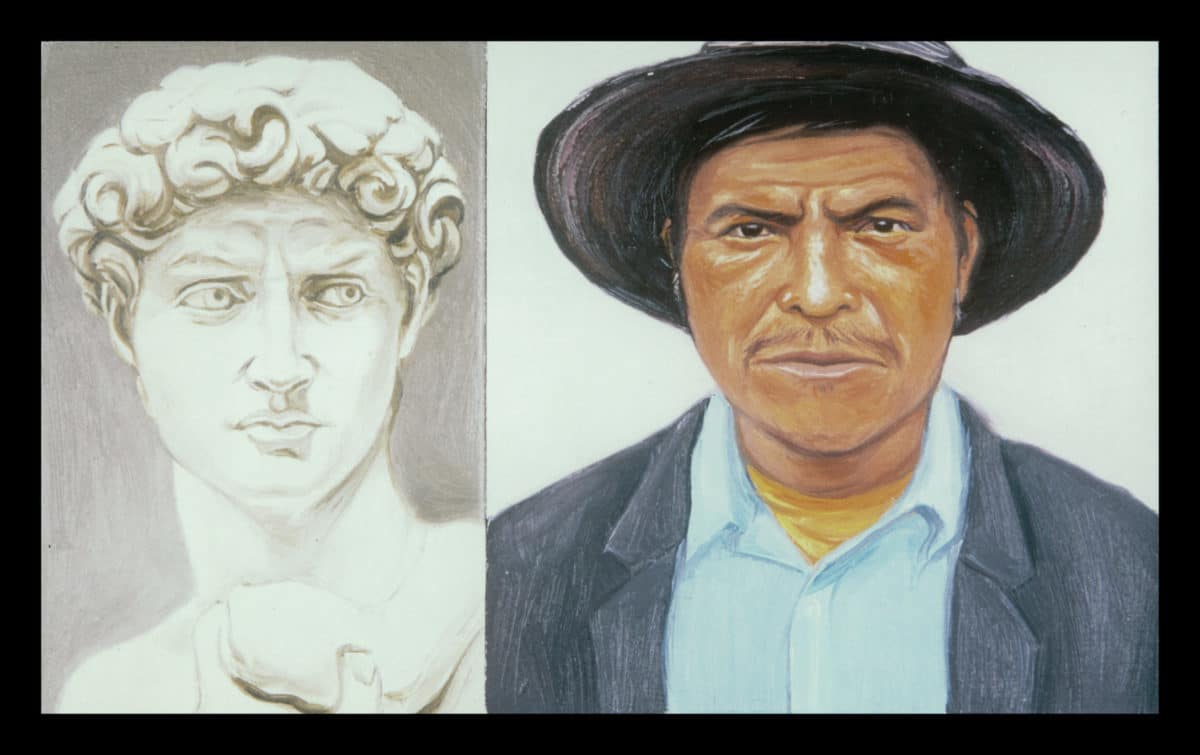

Employment insecurity has always been common for Mexicans in el norte. We have always been expected by the dominant class to play the role of the obedient servant. According to Thorstein Veblen (1899), “The first requisite of a good servant is that he should conspicuously know his place.” This is not to imply that all individuals of Mexican origin in the United States engage in low-wage, dead-end jobs. Thanks to the Chicana and Chicano civil rights leaders of the 1960s and 1970s, including hard-working Mexican immigrant parents and guardians, countless individuals of Mexican origin have had the opportunity to pursue higher education in order to secure employment opportunities unavailable to their Mexican ancestors.

There’s a common saying that countless Mexican immigrants, like my late parents, share with their Mexican American children to get ahead: “Quiero que estudies para que no trabajes duro como yo.”

Sometimes, however, even holding a Ph.D. doesn’t protect you from the gaze of the American racists. I speak from my own experiences.

Speaking of my parents, they are prime examples of how millions of Mexicans immigrants work hard, sacrifice and suffer without economic security so their children have better opportunities.

My father, Salomón, first arrived in this country during the 1950s as a guest worker (or bracero) during the Bracero Program—a bi-national, agriculture guest worker program between the U.S. and Mexico, where millions of Mexicans toiled in America’s agriculture fields. They also helped construct railroads. As a bracero, like his paisanos, my father was sprayed with DDT by the American government and exploited by American agricultural employers. Later, he worked as a day laborer and janitor at a wheel factory, earning $3.25 per hour for over a decade before the capitalist system broke him! (Following the example of corporate America, we relied on welfare for over a decade.)

In short, I want Americans to appreciate and learn from the struggles of the Mexican people in el norte—past and present—during this crisis. Once we overcome this health crisis—which we will—let’s unite and create a society without the haves and have-nots.

My mother, Carmen, toiled as a domestic worker for over 40 years. She started cleaning homes (and caring for kids) of privileged Americans during the 1960s while living in Tijuana. (My older sisters, Catalina and Soledad, also worked as teens during this period to support our growing family.) My other older sister, Ofelia, would care for the younger siblings, including myself. Fortunately, I had my immediate and extended family to rely on, which is the Mexican way.

I’m concerned about the disastrous economic, emotional and health impacts of the coronavirus on the public (worldwide), in terms of myself, I’m neither worried nor panicked given all of what I’ve experienced in my upbringing in the barrio, witnessed and studied over the years. This doesn’t imply that I’m trivializing or minimizing how people are feeling during this horrific health and economic crisis. I am being precautious and following the advice of health experts, such as washing my hands regularly, keeping a safe distance from others and staying at home, among other safety measures.

In short, I want Americans to appreciate and learn from the struggles of the Mexican people in el norte—past and present—during this crisis. Once we overcome this health crisis—which we will—let’s unite and create a society without the haves and have-nots.