This story was written in collaboration with L.A. TACO’s Media Lab class at USC, an incubator for emerging journalists aimed at forging a new path for the future of journalism. Keep a look out for our ongoing series of stories from L.A. TACO Media Lab students.

In a city that is famous for its endless tacos and a handful of Caribbean food gems, Belizean cuisine often gets overlooked.

Belize, which sits in Central America, yet is part of the Caribbean, embodies a dual identity that runs through its food, where Afro-Caribbean spices meet Mestizo corn, Garifuna tradition, and Creole comfort. From the parking lot, The Blue Hole glows a bold, tropical blue, edged with yellow trim that cuts through the muted tones of Gardena’s strip malls. Inside, the brightness continues: the Belizean flag hangs above a room filled with laughter, the scent of coconut rice and fried plantains waft through the air, and soca classics, like “Tiney Winey” by Jamaican legend Byron Lee, spill from the speakers.

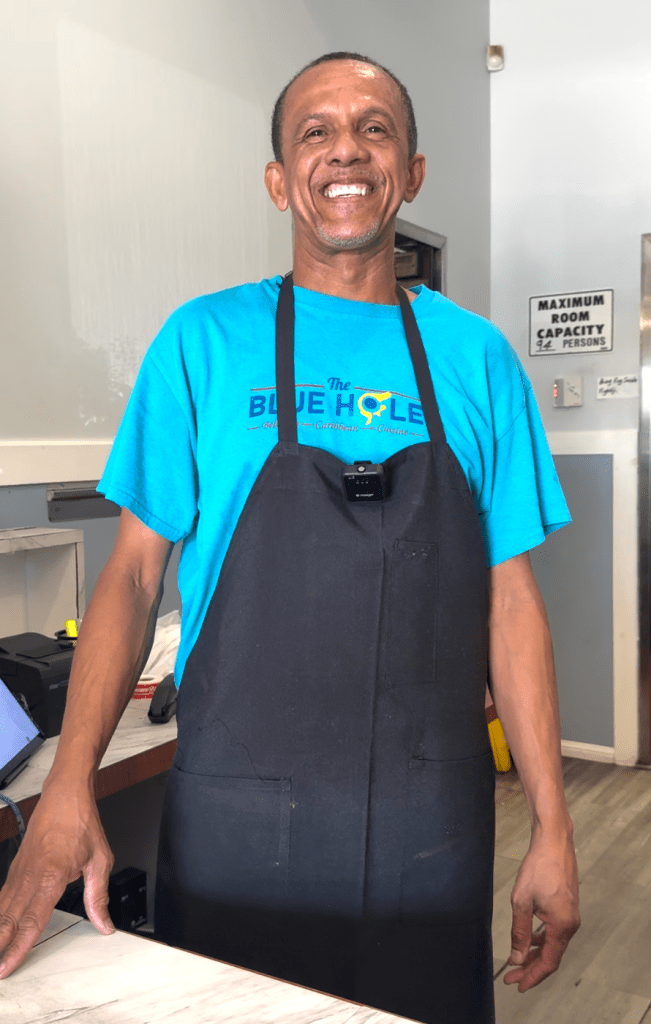

At the center of it all is Leslie Gillett, the restaurant’s food and service manager, partial owner, and resident multi-tasker. He greets customers with the kind of smile that feels personal, not practiced. Every few minutes during our interview, he’s up again, greeting someone or checking on a table. He knows nearly everyone who comes in by name.

Hispanic Heritage Month may have ended, but for Belizeans in Los Angeles, home to the largest Belizean community outside Belize, the celebration continues every day.

For Gillett, Blue Hole is both memory and mission. He grew up in the Corozal District of northern Belize before moving to Los Angeles as a child when his parents sought better opportunities after the country’s sugar industry collapsed.

“I went back a lot,” he says. “So I kept the culture here, and there.”

He still remembers going to Nel and John’s, a Belizean restaurant on Western Avenue that once served as the community’s heart.

“You felt Belize when you went there,” he says. “When it closed, we felt that loss.”

The Blue Hole opened in 2020, when most restaurants were closing instead of launching.

“We started with takeout only … masks, long lines, everybody worried … but the customers kept us going,” he says.

The restaurant is named for the Great Blue Hole, Belize’s famous underwater sinkhole.

“It’s a name that makes people think of home right away,” Gillett explains. “When people hear ‘Blue Hole,’ they think Belize.”

Inside, he has created a place that looks and feels like home. Banana and mango plants fill the corners, and photos of Belizean beaches line the walls. The plating itself is artful, an elevated touch rarely seen in the handful of Belizean restaurants across L.A.

Instead of Styrofoam trays, meals arrive on ceramic plates: domed coconut rice and beans beside potato salad, golden plantains across the edge, and stew chicken served neatly in its own bowl. It’s the classic Belizean “1, 2, 3.”

About 70% of The Blue Hole’s customers are Belizean, with many regulars treating the place like a family kitchen. The rest are locals and travelers who heard about it from friends or flight crews.

“We do not run TV ads,” he says. “It is word of mouth.”

He can list the cities people drive from: Riverside, San Diego, even San Francisco. Flight crews stopped by after hearing about the food mid-flight. Many customers bring visitors to share a plate and a story.

Server Sinclair Flores, who has worked at The Blue Hole for four years, says that’s what makes it special.

“It feels like a piece of Belize brought to L.A.,” he says. “I’m introverted, but working here helped me open up. Plus, being Belizean, it was perfect.”

He smiles when new diners take their first bite.

“We get plenty of new people whose reactions are of enjoyment and find themselves coming back again.”

The dishes carry that sense of discovery. The Orange Walk tacos, named for a northern district, take nearly three days to prepare. The chicken is marinated in spices and recado—a deep-red seasoning paste made from annatto seeds, garlic, and herbs—cooked low until the meat slides off the bone, then layered with a sauce that takes another hour to make.

“It’s juicy and messy,” Gillett laughs. “You’ll need napkins.”

The kitchen follows recipes written by Lucy Guy, the grandmother of Gillett’s wife, who cooked for a big family and, thankfully, wrote down the steps before she passed.

“Belizeans do not always measure,” Leslie says with a laugh. “She did. Time. Ingredients. Everything. We scaled it for big pots.”

Even desserts carry legacy, like Blue Hole’s coconut tarts with crisp edges, and lemon pies glowing under green wedges of local lime.

In the kitchen, one chef, who preferred not to be named, tells me quietly that he only agreed to give me the story because I’m Belizean.

“People don’t realize we have tacos too,” he says. “They’ve always been part of our culture. We just call them by our names.”

His comment speaks to a larger misunderstanding of Belizean cuisine, and towards its mix of flavors that doesn’t always fit neatly into one Latin-American box.

Being a Belizean restaurant in Los Angeles can be a challenge. Many guests pick up a menu, look for dishes they know, and hesitate. Leslie and the servers explain, recommend, and sometimes buy a tamal for a table so they can taste first.

“Once they try it, they come back,” he says.

Word spreads. The Orange Walk taco is now one of the best sellers. So are the salbutes, what Gillet calls an open face taco.

During our conversation, his English softens into Creole whenever another Belizean walks in. The rhythm in his voice changes, musical and familiar.

“Weh di go on?” he calls, laughing as a friend answers back. The sound alone could transport you straight to Belize.

The Blue Hole has become more than a restaurant, it’s a gathering space, an unofficial cultural center where generations of Belizeans reconnect. Older customers bring their grandchildren to taste what they grew up on. Younger Belizean Americans come searching for connection. Even non-Belizeans leave as friends, carrying leftovers and new stories.

As “Tiney Winey” hums through the speakers again, Leslie moves through the dining room like it’s his home, greeting customers by name, trading hugs, and checking that every plate looks just right. He pauses for a moment, watching a family laugh over a table of stew chicken and plantains.

“I just want people to leave full and happy,” he says. “Good food, good people, good energy, that’s Belize.”

In that moment, it’s clear The Blue Hole isn’t just a restaurant. It’s a heartbeat of the Belizean community in Los Angeles, a place where joy, memory, and belonging are served together, one plate at a time.

Blue Hole Restaurant ~ 14008 Crenshaw Blvd. Gardena, CA 90249