[dropcap size=big]E[/dropcap]very Angeleno has at least once or twice in their time here come across the image: a ravishing Aztec maiden who is asleep — or unconscious, or dead — in the arms of a powerful warrior in a headdress. Behind them, a snowy peak and the sky.

The picture of loving embrace is almost as ubiquitous as the Virgen de Guadalupe, which is to say, it is everywhere: on murals on the sides of liquor stores, on calendars from panaderías, on tattoos, and on those blankets sold at the border port in Tijuana. The most commonly duplicated original is by illustrator Jesus Helguera, a legend himself. And while the couple is usually sensually depicted, the theme of the picture is actually rooted in the mountain in the background.

That is the volcano Popocatépetl, which together with Iztaccíhuatl (Popo and Izta), forms a pair of active and dormant volcanoes that are visible southeast from Mexico City on rare non-smoggy days.

Their awe-inspiring twin presence has mystified humans for thousands of years. Helguera’s well-known drawing of Aztec love depicts the origin myth of Popo and Izta, and — this being Mexico — the legend is full of tragedy, heartbreak, and loss.

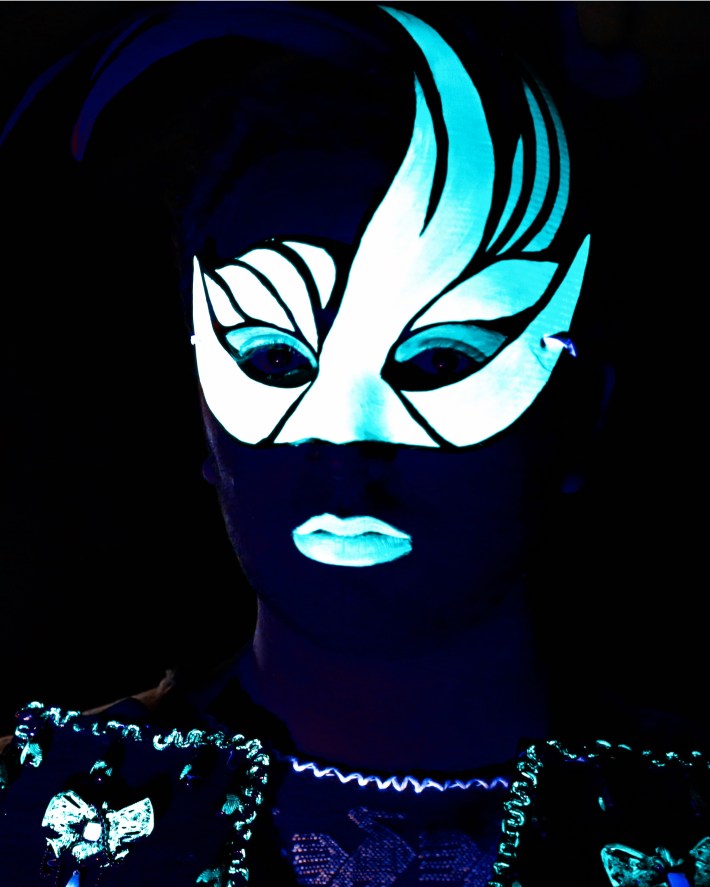

That story is source material for a visually visceral new Los Angeles opera called “El Circo Anahuac,” which plays its last two of four performances this weekend at La Plaza de Artes y Culturas, near Olvera Street. In part designed by well-known local visual artists Lalo Alcaraz and Daniel Gonzalez, the show uses negative light to emphasize neon paint and make-up, creating an arresting sensory experience from beginning to end.

As the legend of Popo and Izta generally goes (it varies in different sources I consulted in English and in Spanish), there was once a great warrior sent off to fight an enemy in the south. Before he left, the warrior swore his love to a princess, and promised to return to her after victory.

The enemy was defeated, but in a terrible miscommunication in the blur of war, word reached her that warrior had died in battle. The princess, heartbroken, dies of grief — or she enters a deep sleep, or a spell of sadness, and this how the warrior finds her upon his arrival.

Devastated, he lights a torch and kneels besides his sleeping love, holding vigil over her day after day, month after month, year after year. Until finally the gods cover them in snow and transform them into mountains: turning the lovers into the curves of the peaks of Iztaccíhuatl, “The Sleeping Woman” who rises to 17,100 feet, a dormant volcano; and the smoking top of Popocatépetl, reaching 17,800 feet, still active to this very day.

“El Circo Anahuac” turns out to be far too short for an audience willing to sit and listen to more on opening night. The opera is an urgent reminder for Los Angeles that, no matter what, carrying out strong original artistic visions — in the toughest of formats, in the toughest of cities — is still a doable thing from the ground up.

RELATED: Azteca Goddess ~ City of Bell

The modest show, staged in a room without favorable acoustics on the fourth floor of La Plaza’s historic old-core building, is written by composer David Reyes and librettist Maria Elena Yepes.

In remarks before ‘curtain’ on opening night, Reyes described himself as a lifelong student of modern classical music. He said the musical idea behind “El Circo Anahuac” was a steady, expectant drum rhythm, which now opens the opera’s overture. Yepes wrote an opera mostly sung in English with instances of Spanish and Nahuatl, a perfectly L.A. blend of languages. A seven-piece ensemble of brass and percussion, noticeably excluding strings, accompany three singers (Rosa Evangelina Beltran, Manfred Anaya, Emilio Valdez) and four dancers (Sheena Castillo, Jesse Maldonado, Danny Cabrera, and choreographer Janelle Gonzales).

Although there’s not a lot of story to cover in “El Circo Anahuac,” the action never lags. The show begins with a circus-like hawker introducing the proceedings, a device that isn’t sustained throughout the opera and is worth exploring further. There is constant movement: the choreography convincingly blends pre-Hispanic influences with ballet and modern styles.

[dropcap size=big]S[/dropcap]taging director Russell Copley and choreographer/artistic director Gonzales make the small room feel expansive and large, even if the lack of microphones on the voices can cause their singing to get lost in the space. But, the colors … a clever use of black light makes for a psychedelic visual palette, highlighting the designs in headdresses, costumes, masks, and animated illustrations by Gonzalez.

“El Circo Anahuac” plays two more sold-out shows, Oct. 13 and 14. In discussions after opening night, the creators, artists, and eager audience members were in certain agreement: the opera could definitely benefit from playing to a larger house, with more resources.

The show’s look and feel ultimately serve as a potent flag to wave for our city today. Anything is still possible in L.A.'s vast arts landscape.

And, if an Afro-Futurist or Afrocentric lens can now lead popular culture and high-art as well as mainstream cinema (see Wakanda), if Black American arts can flourish in the current climate in the United States, so too can anything that places “Aztec” stories and motifs in the front and center.

RELATED: ‘Black Panther’ and ‘Coco’ Prove Diversity Is Good for Movie Business, Panel Says

'El Circo Anahuac,' by Brown Fist Productions, playing Saturday Oct. 13 and Sunday Oct. 14 at 7 pm at La Plaza, is sold out.