[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he best pozolería in Mexico City has no features meant for you to find it from the street but one. It is a single button on an intercom panel at the metal door of a gray stucco-covered apartment building. The button reads “pozole.”

You press the buzzer and someone buzzes you in. Down a tiled hallway, a wonderland awaits that takes the concept of “home-style” to its most hardcore level. The eatery known as El Pozole de Moctezuma sits in an actual converted apartment, and has been in that same spot for more than 70 years. It offers pozole verde, arguably the most "baroque" version of the dish from the currently troubled state of Guerrero, Mexico.

This restaurant in Mexico City makes it so extravagantly, you'd think there'd be a line out the door of the spot daily for the green pozole inside. But instead, Pozole de Moctezuma remains a neighborhood lunchtime-only place, catering to the same cadre of buttoned-down bureaucrats and office workers from the relatively nearby offices of Mexico's federal tax agency, foreign relations headquarters, and the Bank of Mexico, which maintains the country's reliable inflation rate.

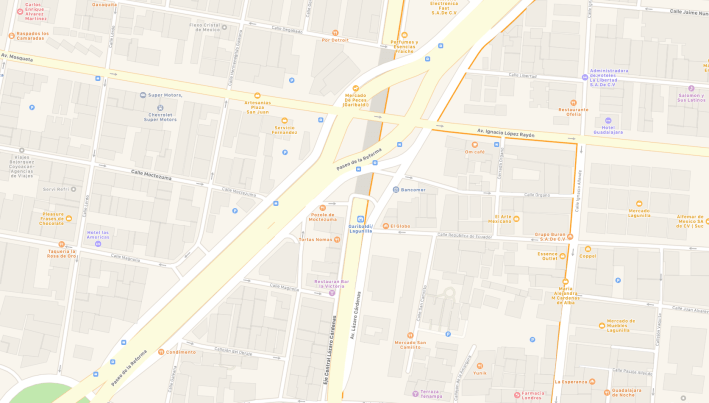

Pozole de Moctezuma is found on a street so short it would barely qualify as a pathway between buildings anywhere else. And while it might no longer be as low-pro as it must have been for decades (it is marked on Google Maps now, as seen below), the place still tends to grab newcomers with the jarring sight of a uniquely foreboding entrance in a city of tens of thousands of restaurants.

I first met a friend there for lunch from Relaciones Exteriores about 11 years ago, and I’ve returned only a handful of times since. I’m usually drawn to the spot unplanned, by an unexpected turn of events in a day in downtown. A sense of defensive urban snappiness is required to cross into this grimier section of Colonia Guerrero — a pocket colonia named for the state of the green pozole.

RELATED: Taco Stands in the Motherland ~DF

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]here are lots of great pozolerías in Mexico City, of course. And plenty of spectacular pozole in other states of Mexico. In each distinct region people swear by diosito that their local pozole or their matriarch’s recipe is the best. But few places that dedicate themselves to the dish raise expectations so dramatically as Pozole de Moctezuma.

That’s why I went along with filmmaker Ricardo Martinez Roa, to meet the manager and owner Geronimo Alvarez Garduño. We wanted to learn the history of this classic Mexico City restaurant, and taste its incredible Guerrero-style green pozole.

[dropcap size=big]P[/dropcap]ozole can be red, white, or green in variety. Together, these colors happen to make up the Mexican flag, which is a good baseline indicator of how deeply the stew is tied to national identity. Pozole’s true central ingredient — like Mexico itself — is corn, a large-kernel variety called cacahuazintle, or “grano” or “pozol,” which is soaked until it becomes large and soft. At some point, if Sahagún is to be believed, human flesh was replaced with pork for the meat base. Five hundred or so years later, pozole is as Mexican as can be. Its signature night is Fiestas Patrias, celebrated overnight between September 15 and September 16.

The dish shines in homes as families gather to celebrate “El Grito,” to drink and eat. Big oversized pots of leftover pozole really, really come in handy the morning or afternoon of September 16 (and/or September 17), depending on how severe the pertinent hangover might be.

At Pozole de Moctezuma, however, the style is more like the "secretary's pozole," or Pozole Thursdays — that is, the celebratory, heavily garnished version of the green pozole as made in towns and cities across Guerrero: doses of diced onion, oregano, ground chile, crumbled chicharrón, and chunks of spoon-scooped avocado. The servers prepare the dish tableside: an egg cracked into the broth, and then, as a final surprise, a couple tablespoons of Guerrero mezcal.

Sardines come on the side.

“My great-grandmother passed it to my grandparents, but to the daughter-in-law, my grandmother. And my grandparents left the business to their daughter-in-law, my mother, and here we are," Alvarez tells us.

"I am the fourth generation," he adds, laughing. "And I hope they don’t leave it to my wife."

RELATED: An Ode to Oaxacan L.A. ~ Friday Nights at Poncho's Tlayudas