[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he informal swap meet is conjured every weekend on Main Street along the corners of 46th Street, 47th Street, 47th Place, and 48th Street, more or less surrounding Holy Cross Catholic Church, which is how street markets across Mexico and Latin American frequently begin: around the temple.

It’s been there for about fifteen years, vendors say. People setting up and selling things, people walking by, buying. With a view of the downtown skyscrapers, the unofficial street market is in so many ways a reminder that the immigrants have already won. Every sensory signal here reflects a north-of-the-border remix of the various cultures of Mexico, southern Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and the traditional African-American current in South-Central that binds them all.

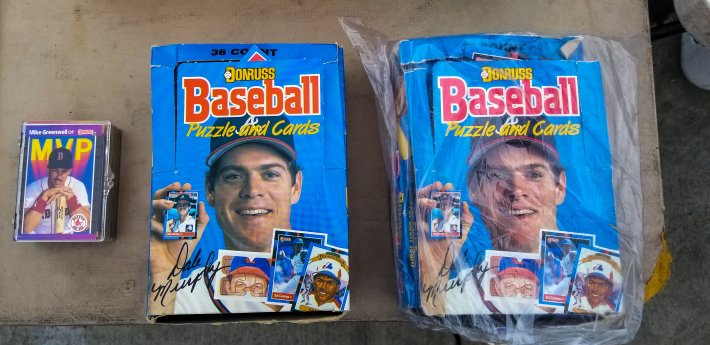

Humberto Yauli, an immigrant who came to the United States from the department of Huánuco, of Peru, in 1999, sits before a folding table on the northside of 47th Street, in front of the public library. On Saturdays and Sundays, from dawn to about sundown, he sells otherwise throwaway-type things that are perfectly sellable in his trained eyes. One day it was a yellowing cardboard box of imported men’s briefs, with a totally 80s packaging design of an oily model. Another time, he offered vintage baseball cards. Yaoli can sometimes be found selling tools or photo frames, anything, really, that he can collect or get his hands on.

His wares are things that were manufactured long ago, far away, and since forgotten. “Kids toys, clothes, what people give to me, or what I buy,” he says.

Next to Humberto are vendors who specialize in used DVDs and CDs, used clothing, fresh fruit, and packages of nuts and seeds that are described as having curative powers for this or that ailment. The area around Main St. is one of several dense stretches of street vending across Los Angeles that are currently under consideration to be designated special vending districts. Rules that would regulate these zones are still being painstakingly drawn out at City Hall.

Yauli and his neighboring vendors started a committee years ago to get to this point. They’ve organized, rallied, attended City Council meetings, protested along with groups of vendors from disparate parts of town. Yauli is always explaining why he does what he does.

“I’ve worked in a lot of things, construction, painting, and lately I’ve been a street vendor, because it’s difficult to find work,” he explains in Spanish. Still, he says, "it's not enough."

"It's a help."

RELATED: 'We'll Believe Legalization Drive When We See it In Practice'

When I first met Yauli, more than a year ago in February 2017, the City Council had only recently decriminalized street vending, a step below legalization. The vote was a victory for the vendors’ cause, but really another incremental step in a long-haul campaign by a variety of organically formed organizations led by people like Humberto Yauli. There was now a gray zone, in which officially an enforcement approach to vending would be abandoned, and the city would begin the process of engaging constituents — from business groups to vendors — on how to proceed in legalizing and regulating.

That process remains ongoing and officials are tight-lipped on the negotiations, but one of the points of contention is how many vendors to allow per block. Clearly, places like Century City or Windsor Square don't need lots of vendors on the corner, but dense areas like MacArthur Park or South-Central already have packed-in unofficial vendor districts, with multiple vendors per block. The current push involves permitting the special vendor zones so these areas can remain roughly as is.

In advocating their positions, the vendor groups are aided by the East Los Angeles Community Corporation, and now they are taking their cause to Sacramento. Currently, the state Legislature is debating a proposed law, Senate Bill 946, that would legalize street vending statewide.

When introducing the bill, the office of Senator Ricardo Lara said a liberalizing sweep was necessary because “sidewalk vendors are more vulnerable than ever.” If a state law prevails in California, legalizing vendors in the world’s fifth largest economy would be a powerful repudiation of Donald Trump.

The current administration’s central domestic hallmark is race-baiting and scapegoating immigrants. A string of high-profile deportation arrests by ICE agents have targeted street vendors in our state. But at the policy level, the Democrats’ control of Sacramento keeps pushing the state farther to the left on immigration matters. Undocumented people are now functionally “legal” in California, participating in the state’s apparatus of schools, healthcare, law enforcement, and as property owners and drivers with state-issued licenses. Humberto Yauli is one of them.

Senate bill 946 is currently breezing through procedural votes with success. And the vendors keep pushing. Rosa Miranda, a longtime organizer of street vendors, says that there are 500 active members in 18 groups that represent approximately 2,000 street vendors overall through ELACC.

[dropcap size=big]H[/dropcap]umberto’s daughter Gisella was a street vendor, too. On March 5, 2014, Gisella Yauli and her small son Dillon Reyes, walked in on a burglary in progress in her house on 50th Street. The robber, a man named Robert Lawrence Ransom Jr., evidently had death in his heart. He tied up Gisella and set fire to the house, killing her and Dillon.

Gisella Yauli was 28. Dillon Reyes was 19 months. When Humberto first told me the story, I almost didn't believe it; it sounded so cruel, so random. He kept photos of Gisella and Dillon at his folding table.

Four years later, this March, Robert Ransom pleaded guilty to killing Gisella and one another woman. His second homicide victim, Margarite Evans, was found shot and dying on 93rd Street on March 2, 2014, three days before the attack that claimed the lives of Gisella and Dillon.

In April of this year, an LA Superior Court judge sentenced Robert Ransom to 85 years in prison for killing Yauli and Evans, and for attempting to kill a teenage girl he had kidnapped. The dead victims’ lives were cut short when their paths simply crossed with that of a killer.

But for the Yauli family and their network of neighbors and street vendors, the deaths of Gisella and Dillon are beyond a heartbreaking tragedy. The case is also an extreme crystallization of the threats that vendors with precarious incomes face on the streets in the poorest sections of the city.

Violence, assault, and extortion by street gangs are considered common among vendors in Los Angeles. Earlier this year, video caught the incident of an early morning vendor-jacking by a large group that left fruit seller Pedro Daniel Reyes badly beaten and injured. Last year, elotero Benjamin Ramirez was assaulted and had his cart flipped over by a ranting neighbor, in a now-famous video clip. Unfortunately, Ramirez the elotero recently got hit and injured again.

On top of the criminal threat, of course, is the threat posed by hostile law enforcement or county inspectors. Vendors face arrest, citations, and the confiscation of their goods; they tell epic stories of past police harassment.

Today, Yauli says things have gotten safer on his street. People cooperate and get along when the swap meet happens. Vendors set up as early as 3 am. Lately, police harassment and arrests have died down — at least here. Now cops cruise by and wave.

Gisella left another son, and the two boys’ father, Oscar Reyes, who was then a longtime chef at Henry’s Tacos in Studio City. Since Gisella died, her family and friends get together and hold a modest memorial service for her and Dillon every year. At last year’s memorial, at a second-floor apartment overlooking a park, women and men crammed in to listen to a pastor talk about God and forgiveness. Afterwards, the family laid out Peruvian dishes: an adobo in green sauce, fried rice. Humberto wore the uniform of a working-class man at the center of a somber occasion. Dark sunglasses and a crisp white T-shirt with a sporty name splashed over it.

To this day, Yauli seems to walk with deep emotional scars over what happened to his family. He sighs and his voice quivers when he is pushed to recall his daughter and grandson's deaths. He tells me he remains ambivalent about the fate of their killer — a life in prison, after taking three innocent lives. Tragedy just strikes. And there is nowhere to really turn.

“A parent expects to go before,” he tells me, in a warm Peruvian accent. “A parent never expects that one of his children would go first. ... I thought about taking my own life …”

RELATED: Casa de Clarke: A Model For Unsupervised Homeless Housing Opens in Highland Park

[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap] year ago, Humberto lived in a worn-out RV that he parked near his spot on Main Street. When I began visiting him again a few weeks ago, Humberto informed me that he had lost the RV to unpaid tickets. This happens a lot to people who fall on hard times and whose last resort is their vehicle — one step above living on the streets.

He’s now staying with his son-in-law Oscar. Like other people in Los Angeles living in that space between having a home of one’s own and not having one, Yauli doesn’t intend to leave the South-Central neighborhoods around Main Street. This area is where he and his daughter and grandson lived. He now says his life revolves around his surviving grandson; Humberto takes him to school and prepares his meals.

Yauli says he's sensitive to businesses who complain about vendors' use of the sidewalks, or who argue that the street vendors negatively impact their businesses. But he also says it's simply not true that the two sides are enemies.

"We are not their rivals. On the contrary, if we don’t have something someone is looking for, we send them to the stores," Yauli says. "We’re not sending them to Wal-Mart or Target. We tell them to go to the closest little store."

He declines to offer a figure on how much he makes, aware of the risks, but explains that it is not enough to live on — not by far. "It doesn't cover everything," he says.

He gets food stamps, and finds the oddest kinds of jobs to patch together his needs. Yauli is cautious yet optimistic about the future of his livelihood as a street vendor in Los Angeles. He says the vendors themselves have grown, become more committed to their cause, and are staying hopeful for justice and security on the streets of Los Angeles.

"L.A. needed to organize itself," Yauli says. "I know it’s going to be hard for the vendors, it’s hard to get people organized, but we have to do it."

RELATED: An Ode to Oaxacan L.A. ~ Friday Nights at Poncho's Tlayudas