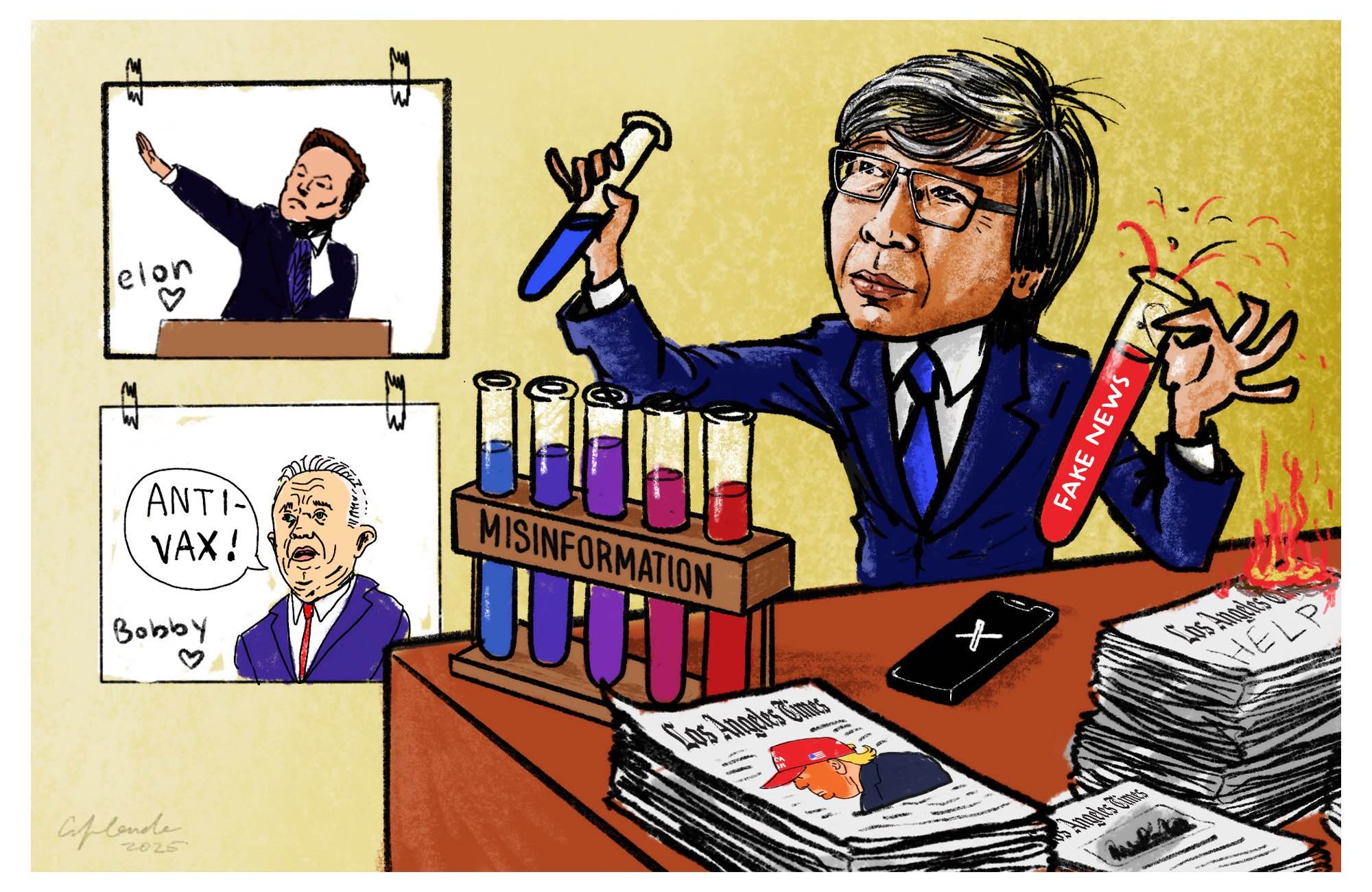

More than 20,000 people cancelled their subscription to the L.A. Times last November to protest billionaire owner Patrick Soon-Shiong and his upheaval of the Times’ editorial page. The changes, compounded with a series of tweets over the previous year, were part of a clear effort to establish allegiance to the current administration.

According to Mark Stenberg, a media reporter at Newsweek, the publisher has also lost advertising business from partners like Netflix, in part due to the changes made to the company by its billionaire owner.

Yet, President Trump has never been favorable to the press. In his first three months in office, he reconstructed the layout of the White House press room, barring access for globally accredited newsrooms like the AP while magnifying right-wing pod-casters.

“We are talking about an administration that is openly hostile to a free and independent press,” said Gabriel Kahn, a professor of Professional Practice of Journalism at USC.

Dr. Soon-Shiong, a pharmaceutical baron, is among the billionaire media owners who shifted their policy since the election – a phenomenon Kahn deems Gleichschaltung, a chilling Nazi German term meaning realignment.

“A lot of what they’re doing is not to provide their readers with an additional perspective or help them sort of navigate this as consumers of news, but to appear more friendly to the administration for either access or for favors,” Khan said. “[Soon-Shiong] evidently feels that he is going to need federal funds, research, dollars, whatever, in order to make a success of some of his pharmaceutical businesses and the places where his bread is truly buttered.”

This is just one more knock to the declining influence of legacy news media. For smaller, hyper-local newsrooms, especially those that rely on crowdfunding and grants, the impact of national politics is less pervasive.

“Councils are still meeting,” said Alicia Ramirez, the founder and publisher of the Riverside Record. "Your county board of supervisors are still meeting. Your school boards are still meeting. They are still making sure that contracts are being negotiated with unions. All of this daily life is still happening, and we are still reporting on that."

The basic function of local news is to inform people about their communities, from public safety and policy to disasters – most recently, local outlets crucially covered the deadliest fires in L.A. history. Regions that lose news outlets correlate with increased partisanship, according to the News Literacy Project.

However, the nature of the stories themselves is undeniably changing. Ramirez, for instance, recently wrote about the Temecula Valley Unified School District’s decision to ban transgender girls from participating in girl’s sports – a resolution rooted in the anti-trans rhetoric of the GOP.

“We are about two and a half months out from his inauguration, and a lot of these policies are starting to have a real impact. It’s started to trickle down into our local communities,” she said.

The Dímelo desk at USC’s Annenberg Media is one of the first responders for reporting immigration and deportation matters in the school community. Dímelo editor Katherine Contreras Hernandez recently published a Know Your Rights guide to help navigate ICE encounters, written by Gian Marco Velásquez.

“It did really, really well," Contreras Hernandez said. "I think the people that are impacted so closely are those that are looking to read something that Dímelo produces. Especially because it can be easy to find dehumanizing depictions of immigrants in national media. They've come to us because they see us as a reputable source.”

The spread of unverified news is growing within communities. In findings from Pew Research Center’s American News Pathways project, exposure to certain false and unproven claims correlates closely to using Trump as a news source and reliance on social media as a news source.

“I think that is such a crucial part of this new media landscape that we're in,” Ramirez said. “There are information ecosystems that exist outside of the large mainstream media outlets – there are Facebook groups and chats, Instagram, TikTok – where people are able to cultivate an audience from and share information about.”

Misinformation and disinformation online can be attributed partially to political division. According to the American Psychological Association, political “echo chambers” enable the spread of falsehoods and impede factual corrections.

A flawed business model is also responsible as algorithms favor the profitability of sensationalized information and “rage bait” over factuality.

“You’ve got to have healthy local news in order to have healthy national news and international news,” said Kahn, who is also the founder of data-driven and L.A.-based newsroom, Crosstown. “If you can't establish facts at the local level first, then the potential for an eroding of a fact-based reality becomes much greater, the higher up the food chain.”

Though local news is delivered, it is difficult to compete with the noise coming from the presidential office, Kahn said. This is especially true for the average “drive-by” news consumer, or people who get their news passively.

“As terrifying as it is, a lot of it is kind of entertainment and theater. And it's like, ‘can you believe what he did today?,’ and not like, 'Why are the homeless encampments on my block increasing in size?’” Kahn said.

Ramirez attested that readers of the Riverside Record tend to be active in their communities already. Her biggest concern is one shared by many local newsrooms – how reliable news sources can adapt to reach more people.

“You have all of these smaller news outlets who are providing this vital information to their own communities,” Ramirez said. “News is expensive. It's hard to make, it takes time, and I hope I can get more investment in it, because we all know what happens when local news dies.”