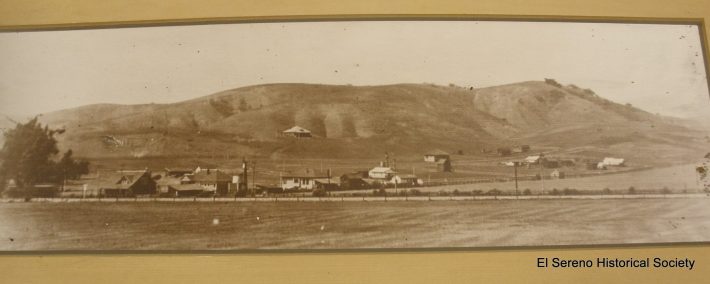

There is an oasis in El Sereno called Elephant Hill. Home to rabbits, reptiles, owls, hawks, coyotes, and even a bobcat (I crossed paths with its round, fuzzy tail once), it has 360° views that take your eyes on a sensory ride from downtown to the mountains and Catalina Island on a clear day. From above, the hills form an elephant-like shape. Locals have long referred to it as “The Heavens,” a name derived from a locked gate at an entrance that folks referred to as “The Gates of Heaven.” Goats, cows, and chickens roamed the hill when the Lifur Dairy Farm stood below it on Harriman Avenue and Pullman Street. The dairy closed in the late 1940s, but an underground stream still flows inconspicuously beneath its 110 acres that awake at dawn to a symphony of roosters.

To the west is the elm tree-lined Collis Avenue, where open houses are now staged, and newcomers priced out of nearby Highland Park snatch up $1.5 million homes like they’re going out of style. The cast and crew of Brother vs. Brother even set up shop here, filming an episode of their glorified house flipping HGTV show sin vergüenza. Home prices have also drastically increased to the east, but on Huntington Drive, businesses have mostly stayed Brown. Elephant Hill is one of Northeast L.A.'s last and largest open spaces, where native black walnut trees are rooted resiliently like the previous locals. Still, its habitat is being destroyed by illegal off-roading and dumping.

Many in the neighborhood feel the land is sacred and want to protect precious oak and walnut woodlands, coastal sage scrub, and other native plants like monkey, lupine, and fiesta flowers that bloom beautifully in spring. These natives struggle to survive amidst invasive yellow mustard that fools us with their whimsical charm and roads widened by off-roading, which shrinks their habitat.

Elva Yañez is a protector of the land. In 2003, she saw land surveyors come out to her quiet, close-knit street below the hill, reigniting community opposition to poorly planned residential development that started back in 1984. What ensued was a six-year battle with a notorious developer named William D. Foote, whose Newport Beach-based company SWD Communities, LLC sought to build 24 luxury homes in a neighborhood that once offered affordable housing for working families.

“This developer had a tremendous amount of money and influence and bullied his way through the approval process, but we had people power,” said Yañez, 68, seated on a patio chair in her drought-tolerant front yard that gives rise to Elephant Hill. Born in Boyle Heights and raised in Monterey Park, she bought her home in El Sereno in 2001. “His plans called for stripping the central ridge of the hill to bedrock, building homes and retaining walls on compacted soil unsuitable for construction, and destroying two natural drainages and an underground spring.”

Drawing on her work experience waging local public health policy campaigns, Yañez began talking with neighbors and learned about earlier efforts to stop development before the real estate market crashed in the 90s. Her daughter, Alana Yañez, helped with door-to-door outreach and organizing, the foundation of their campaign to stop the development. She consulted with local open space advocates and assembled a team of experts. It included the Latino Urban Forum, local conservation agencies Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy (SMMC) and the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority (MRCA), and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). She even made a career change, going from fighting big tobacco to working at the Trust for Public Land.

With the help of allies in the city government, community members, and environmental organizations, Yañez made a slew of eye-opening discoveries, including that the developer illegally expanded his project by 50%, going from 13 to 25 acres, and an incomplete 20-year-old Environmental Impact Report (EIR) that made no mention of the water running beneath the hill, which posed a severe risk of landslide. She remembers that day well.

“It was 2006 on Good Friday, and it rained heavily that week,” said Yañez, who felt like she had two full-time jobs amidst a battle that birthed the Northeast Hillside Ordinance (NEHO), a zoning regulation that protects hillsides like Elephant Hill. “These guys were installing fences around the developer’s property, and their backhoe went into a sinkhole right there [points to the base of the hill]. I was jumping up and down because we now had proof of the underground water system.”

“I call LAPD, and they don’t show up until two or three hours after the off-roaders leave and sometimes never...”

The city required the developer to undertake an additional environmental review. In response, the developer sued. Finally, in 2009, the city settled with Monterey Hills Investors for $9 million and acquired 20 acres of Elephant Hill. In 2014, the MRCA purchased five acres from the city to create a hiking trail. There are over 300 individual land owners, which makes acquiring land difficult. Still no trail, Yañez has a new fight: the daily off-roading that wreaks havoc on the hill and keeps her neighbors up at night.

Elephant Hill has long been the spot for off-roading, partying, and making out in cars, but today off-roaders use social media, YouTube, and even Yelp to promote it. People drive from as far as Huntington Beach to revel in its wild, wild west vibe, but in the heart of northeast L.A. They haul their trucks, ATVs, and sedans (yes, Honda Accords risk the dangerous descent) recklessly past “No Offroad Vehicles'' signs and up steep hills creating dust clouds that blanket homes below.

On the mesa, they egg on friends who do donuts in pick-ups, their wheels shooting off bullets of mud. Some dump beer bottles, fast food wrappers, and other remnants of a good time and nearly run over folks out for a hike, creating an unsafe environment for people, plants, and animals alike. Off-roaders are seeking recreation and relaxation. On a recent visit, two guys sat peacefully on top of the hill in collapsible chairs, listening to reggae and eating tacos made on a green Coleman camping stove propped to the door of their tan SUV. They were frustrated with the trash and excessive partying but unaware of the scars they left on this precious piece of open urban green space. Many vehicles get stuck, and drivers knock on doors and windows of nearby homes at all hours of the night, asking for help.

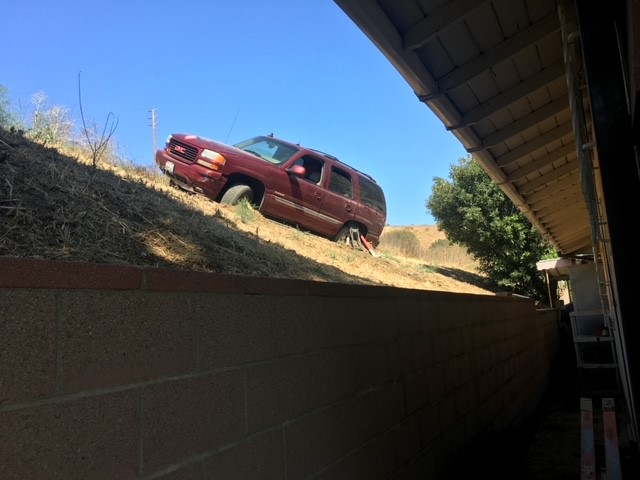

“In 2019, I had knee surgery and was in and out of sleep in my room,” said Ruben, 54, who didn’t want to disclose his last name. He’s been living at the base of Elephant Hill for 26 years and regularly confronts off-roaders in his backyard. It usually ends with them peeling out and leaving him pelted by rocks in a cloud of dust. “I got woken up by rocks hitting my window. I opened the curtains and saw this truck trying to get out. The more it tried, the closer it got to my house, so I opened the window and started yelling at him to stop. I went out, and this guy had a big kitchen knife in his belt on the side of his pants and said, ‘Oh, my friend said there was a trail here.’”

Ruben called LAPD, who came three hours later and claimed the guy was a known gang member. The cops drew their guns on him right as Ruben’s daughter came home and yelled at her to get inside the house. A helicopter hovered right above his house, and neighbors gathered outside after seeing a caravan of cop cars roll up to the scene.

“There I am barking at this guy by myself, and they need all this backup,” said Ruben, “They arrested him because apparently the vehicle was stolen.”

The vehicle wasn’t stolen and was released back to the owner responsible for getting it out. A week later, the guy came back with a shovel and tried digging it out, leaving dirt all over Ruben’s house. The truck wouldn’t budge, and Ruben and his wife couldn’t sleep in their bedroom for weeks. After multiple calls to José Huizar’s office, the vehicle was finally towed away.

“I call LAPD, and they don’t show up until two or three hours after the off-roaders leave and sometimes never,” said Ruben, who was harassed by a motorcyclist that broke his ankle after crashing his bike and had to leave it behind his house. When the bike was stolen, he blamed Ruben. “This was way before defunding the police. When they show up, they use that damn excuse every time, ‘Well, since we’ve been defunded, we can’t really patrol.’ We don’t want to hear revving every day or someone screaming because they're stuck. Once off-roading stops, the community can actually enjoy it as a place to walk and hike.”

During the lockdown period of the pandemic, many folks in the neighborhood started exploring Elephant Hill on foot more, but walking towards a group of trucks doing donuts and having to dodge them as they drive by, kills the naturey vibe.

“People stopped hiking, running, walking their dogs up there,” said Ruben, who’s seen an off-road vehicle start a fire on the hill when the hot catalytic converter drove through dry brush. “Nobody wants people hauling ass 80 miles an hour and slowing down three feet away, leaving you in the dust.”

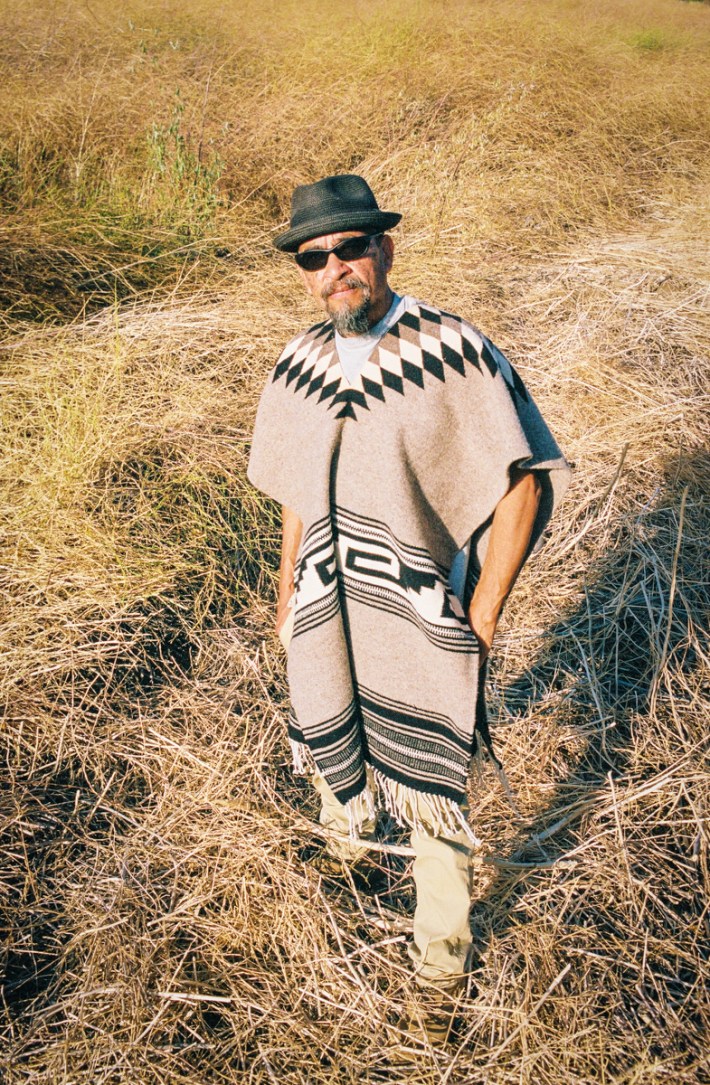

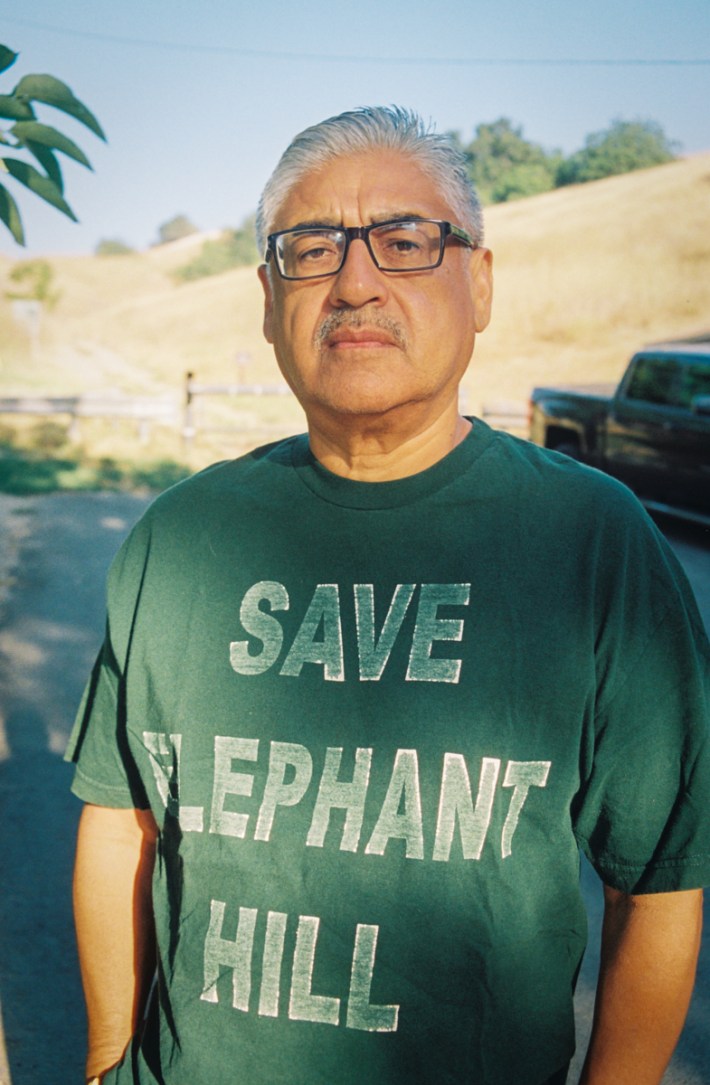

The community didn’t fight this hard to see off-roaders destroy the habitat and terrorize neighbors. Yañez, her daughter, and longtime resident and environmental justice activist Hugo Garcia run Save Elephant Hill, a grassroots organization that raises awareness about land use and conservation issues that first led to problematic development and now off-roading. They post videos of the spectacle, including one of the plumes of smoke created by a Mini Cooper that caught fire last month and an actual barbecue on the hill that’s a designated high fire hazard zone. Yañez has witnessed an elderly couple from South Pasadena joyriding in a zebra-print Jeep and an 11-year-old boy who had to be airlifted after crashing his motorcycle without a helmet.

When the pandemic created an onslaught of off-roaders, Elva encouraged the MRCA to fund an ecological assessment conducted last year by conservation biologist Daniel S. Cooper, which revealed the sad truth: informal roads have increased in size and number by more than 60%. After Cooper’s report, Save Elephant Hill created a mitigation plan that includes posting “No Unauthorized Vehicle” signs at all access points, regular enforcement, installing gates that keep out off-roaders but allow access to emergency vehicles and property owners, and finalizing the proposed MRCA trail that will run from Pullman to Lathrop Streets.

“This environmental injustice would never happen in other, more affluent communities,” said Yañez. “Residents would raise holy hell, and landowners would demand action by the government. Historically, El Sereno has been neglected and plagued by poor land-use decisions, and the median running down Huntington Drive: poor land use.”

Fernando Gomez, Deputy Executive Officer/Chief Ranger for the MRCA, enlisted rangers to patrol their eight acres (they acquired three more since 2014) of land five days a week to try and stop off-roading. They’re working with LAPD’s Hollenbeck division and the off-road unit to enforce the parts of the hill the city owns, but can’t enforce private property. Individual land owners need to sign a release form and give consent in order for LAPD to patrol their parcels. Gomez said the MRCA plans to develop the trail but needs to acquire more land to make it accessible.

Some in the neighborhood grew up off-roading on Elephant Hill. Gary Lunsford, 67, moved back into the house he grew up in after his mother passed with his second wife, Christine Lunsford, a childhood friend he used to play with on his tight-knit culdésac. His father built the house at the foot of Elephant Hill in 1945, living in the garage until it was completed in 1955. It was only the third house built on the street when a ranch with horses and donkeys was nearby. His grandma bought a goat from the dairy farm next door before it closed, and Gary fondly remembers drinking goat milk as a kid. At 13, Gary’s dad bought him a motorcycle, and he grew up riding behind his house during the 60s and 70s with family and friends.

“I'm a renter,” said Aeschliman, who wants the mayor to declare a trash emergency. “It's not like I'm trying to clean up to increase my property value, and I just want to live in a place that doesn't suck.”

“Every Saturday and Sunday, cars would line up on top of the hill,” said Gary, who’s seen his fair share of off-roading tragedies. In the 70s, his friend died when his truck crashed on Elephant Hill, and another friend and mentor lost his life off-roading. “There must have been 100 people riding or watching, but they started kicking everybody out after a while because the police and fire department were here hauling somebody off every weekend. It was dangerous.”

Save Elephant Hill wants to change the narrative. In addition to community organizing, they’re working with Clockshop to plan a series of public art programs that raise awareness about Elephant Hill. They’re encouraging the MRCA to finalize the trail to increase public use and build a task force to address problematic off-roading and dumping. They also teamed up with other local land protectors like Micah Haserjian and Brenda Contreras, the husband-wife coalition behind Coyotl + Macehualli, which is fighting to stop the development of new homes on the hillside behind Eastern Avenue and Lombardy Boulevard in El Sereno. Back in April, Elva got in touch with the Off Highway Motor Vehicle Recreation, a division of the California Department of Parks and Recreation. She invited them to assess the hill in June and hopes they can help stop off-roading. Connecting with property owners of the Elephant Hill parcels being affected by off-roading and illegal dumping is crucial.

The trash is relentless. Construction crews sneak into one of seven unlocked entrances and dump leftover roofing material, tile, concrete, carpeting, and drywall, pocketing money meant to pay for legal dumping. Defunct boats, overturned cars, and even a coffin from Corona have all been dumped on the hill. Overflowing trash bags and tires are everywhere. Neighbors created makeshift metal netting to try and stop land erosion and “gates” made out of concrete and tree stumps to prevent unauthorized vehicles from entering certain areas.

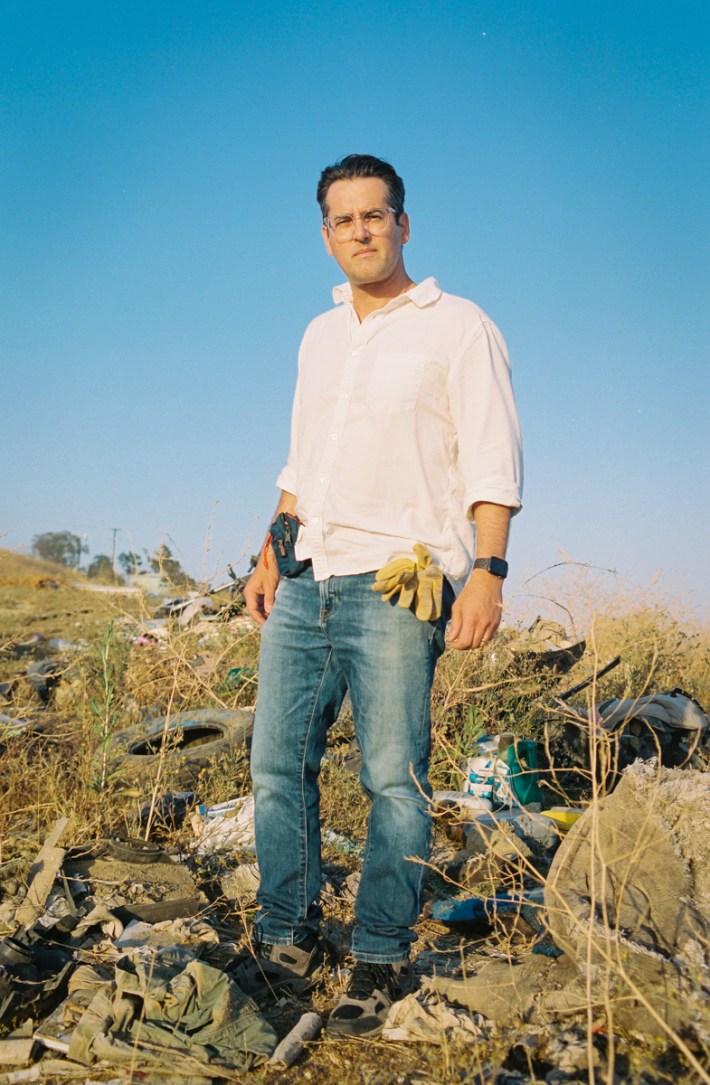

“You go to open, natural spaces, and you want to see birds flying around, maybe catch a glimpse of a coyote, some quail,” said Christian Aeschliman, 45, who’s been organizing clean-ups on Elephant Hill since 2019 and recently started planting natives on the down-low. “You don’t want to see squirrels coming out of their burrow beneath cabinetry that’s been there for years. This animal has built their home in trash. I’ve seen bunnies hop out of the springs of a deteriorated old couch. It’s depressing.”

Born in L.A. and raised in the San Gabriel Valley, Aeschliman’s parents immigrated to the U.S. from Argentina, and his first language was Spanish. He fell in love with El Sereno because it reminded him of the communities of El Monte and Baldwin Park, where he grew up. He posts inspiring before and after pictures on his Heroes of Elephant Hill account to motivate folks in the community to get involved in protecting this sacred space. His crew has easily cleaned up 15 tons of trash, which has to be hauled down to his house in borrowed pickup trucks to report it for pick up using the MyLA311 app. LA Sanitation won’t pick up trash on Elephant Hill. They only pick up from physical addresses, not “paper” streets (streets that only exist on maps but haven’t been built) that are impassable for vehicles and not maintained by the city.

“Our big trash trucks can't get up there. It’s really steep terrain, and we don’t have vehicles to climb the hill and remove illegal dumping. It has to be brought down to a level. We have to consider the safety of our highly trained staff and the vehicles.

Stern said the only way LA Sanitation could remove the trash plaguing Elephant Hill is to park a truck right by one of the access points and bring it down. A service request would first need to be made by calling 311, 213-473-3231 or via their MYLA311 online system or MyLA311 mobile app. Another option is to call Sanitation’s 24/7 Customer Care Center at 1-800-773-2489. In the end, Stern said contacting El Sereno’s CD14 council office at 213-473-7014 to report trash on the hill is probably your best bet.

“We don't proactively go out and search for illegal dumping in public rights of way,” said Stern. “But there is funding for teams to address illegal dumping in the current budget being discussed by the city council.” Last year, CD14 signed a contract with LA Conservation Corps (LACC) to help fill the gap with LA Sanitation to keep streets clean and collect bulky items. According to Julio Torres, field deputy for CD14, it would take highly coordinated efforts between all three entities to secure a truck that could pick up trash on the hill.

“I get it, and there are more pressing issues on people's minds,” said Yañez, who believes a well-coordinated, multi-agency response to stop illegal off-roading on the hillside shouldn’t be this hard. “But this is publicly owned land, and people don't feel safe walking up there. We have to protect it.”

Elephant Hill has 12 access points, two of which are maintained by the MRCA. The remaining ten entrances are all unsecured or without a gate, and one entrance has a lock that keeps getting broken. The city passed a motion to pay for installing gates at Elephant Hill entrance points.

“The cost for the gates is going to come out of CD14 discretionary funds,” said Pete Brown, Kevin de León’s communications director. “The intent is to prevent any illegal dumping activity not authorized by the city or property owner,” Brown said the city’s in the construction phase and will communicate with all the individual landowners about the gates being installed.

Aeschliman also organizes makeovers at his local El Sereno post office, repurposing mulch that keeps getting dumped at the Burr Street entrance of Elephant Hill by spreading it in the parkway. The native plants donated by Artemisia Nursery that he planted there and watered for weeks were stolen. He was heartbroken but continues to motivate folks to clean up the neighborhood. A construction worker even showed up to one of his clean-ups and confessed to dumping on the hill. He found redemption in the selfless act of picking up trash.

“I'm a renter,” said Aeschliman, who wants the mayor to declare a trash emergency. “It's not like I'm trying to clean up to increase my property value, and I just want to live in a place that doesn't suck.”

Amid a climate crisis with everyone trying to get off fossil fuels, it’s essential to protect precious pockets of open spaces like Elephant Hill that provide a hit of clean air amidst a smog-choked city. But like every problem in the community, the issue has to be prioritized by our elected representatives and agency leaders.

“I get it, and there are more pressing issues on people's minds,” said Yañez, who believes a well-coordinated, multi-agency response to stop illegal off-roading on the hillside shouldn’t be this hard. “But this is publicly owned land, and people don't feel safe walking up there. We have to protect it.”