Not far from Union Station in downtown Los Angeles, a crowded line of cars take turns crossing.

In front of the Metropolitan Detention Center, many sit in their cars, oblivious that Francisco Cota, a 15-year-old Latino accused of murdering a local shopkeeper, was dragged up the street, repeatedly stabbed, and lynched above the intersection over 160 years ago in the heart of El Pueblo de Los Angeles.

A few blocks away at Temple and N Spring Street, at least eight more men were lynched from 1855 to 1863 in broad daylight among a large armed crowd. These lynchings took place where L.A.’s first courthouse and jail used to stand, now replaced with City Hall. Further down Temple at its intersection with Broadway, Miguel Lachenal was lynched by a violent mob in 1870—and historians believe over a dozen more lynchings occurred at this site. Not far is the Fort More Pioneer Memorial, which doesn’t mention the murders that happened at that exact place, with all but one of them lynchings of Latinos. There were also many other lynchings sites across Southern California in El Monte, Santa Ana, San Gabriel, San Pedro, Ventura, and San Luis Obispo, as well as in Northern California.

Cota was one of the 547 Latinos lynched in the United States and of 143 Latinos lynched in California from 1849 to 1928. Latinos, primarily Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans, are the largest group to be lynched in Los Angeles and throughout California and the second largest group to be lynched in the nation.

As conversations about lynchings in the United States have rightfully been widely focused on killings of African Americans in the South, California’s history of lynching hundreds of people—including at least 41 Native Americans, eight African Americans, 29 Chinese, over 100 Mexican nationals and 6 Chileans—remains largely unknown.

California was the site of 352 documented lynchings.

“We never hear about Francisco Cota. We never hear about the atrocities against Mexican Americans. That history is virtually erased,” said Irma Beserra Núñez, who was appointed to be a member of El Pueblo de Los Angeles earlier this year.

After a lifetime of passion for understanding her cultural heritage and over 260 years of her family tree intricately tied with California history, Beserra Núñez is now leading an ad hoc committee at El Pueblo to advocate for a Mexican American-Latino historical monument in Los Angeles to recognize the erased history of these lynchings and memorialize those who were sacrificed.

“This is an effort to document the history of Mexican Americans and Latinos and what has happened to us, and how we can begin to heal our city and our nation,” Beserra Núñez said.

History of Lynchings in the West

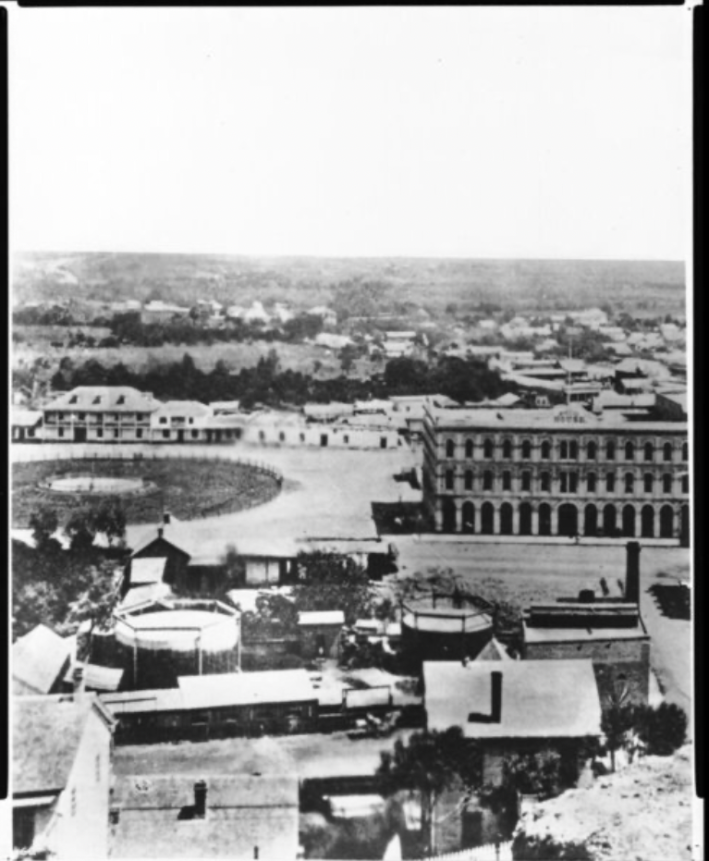

The Spanish and Mexican periods of Los Angeles lasted between 1769-1850, and the land was originally inhabited by the Tongva tribe, or Gabrielinos, for a millennia. During the latter years of the combined Spanish and Mexican period, streets like Sepulveda, Pico, Lugo, del Valle, Ybarra, and more were lined with adobe homes and the families who built them.

Mob violence against Mexican people began after the Mexican American War and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which agreed that the US-Mexico border would begin at the Río Grande river — anything north became US territory. Mexico gave up its claim to Texas, and the US annexed California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and parts of Colorado, Kansas, and Utah.

Among annexation agreements, the US also agreed in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to protect the property and civil rights of Mexican nationals who now found themselves living in the US. Mexicans and Anglo-Americans were now cohabitating after being at war for three years.

According to William Carrigan, professor of history at Rowan University and author of Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, 1848-1928, one of the main factors that led to the lynching of Latinos in the west was economical and land competition involved with mining jobs and freight running during the Gold Rush, as well as cattle, horse and land theft. Often Latinos were accused of theft or murder, used as a justification for lynching by violent mobs, but they weren’t granted any due process to prove their innocence. Some of the victims had been dragged out of their jail cells by an angry mob.

Another factor that led to this violence was racial and ethnic prejudice against Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans as many in the US developed prejudicial ideas about catholicism, Mexico, Spanish speakers, and Indigenous culture, said Carrigan. Many in the US saw Mexicans as a “mestizo” or “mixed” population between Indigenous peoples and Spaniards. The third factor, Carrigan said, was fluctuating tensions at the Mexican border — when these tensions would increase because of new arrivals or livestock, so would mob violence. This was at a time when the term “lynching” was not too common and sometimes would be referred to as “an execution by a vigilance committee.”

The first documented lynching of a Mexican person was in Texas in 1849. In 1851, a Mexican woman named Josefa Segovia was lynched in Downieville, California, after being accused of stabbing a white man who had been harassing her husband and herself. Her last words were, “I would do the same again if I were so provoked.” She was hung off the Jersey bridge overlooking the Yuba River, about 100 miles from Sacramento. She is currently the only known Mexican lynching victim out of hundreds in California that has a monument and plaque in her memory.

Los Angeles saw its first documented lynching in 1852 when an unnamed Native American was lynched in San Gabriel after being accused of murder. Four months later, two Mexican men named Jesús Rivas and Doroteo Zavaleta were lynched in Los Angeles, also accused of murder. By the end of that year, Los Angeles County has lynched seven people, all but two from Sonora, Mexico, and was one of two counties to lynch the most people that year, along with Calveras County, which also lynched seven people that year.

For much of the early periods, Mexican revolutionists’ efforts won some allies, but they weren't able to make a significant impact until the 20th century, when the number of whites lynched decreased and lynching became known as a racial issue, according to Carrigan. In 1890, Mexican diplomats became involved in advocating for the protection of Mexican nationals on US soil. During this time, the US began to care more about good relationships with Mexico and listened more to the diplomats, de-escalating tensions.

Spanish-language newspapers such as El Clamor Público were highly critical of lynching of Mexicans, while others had neutral accounts of lynchings with little to no editorial comments. When some newspapers were critical of lynching, it was often more because of a lack of due process than any racial dimesions, said Carrigan.

The US eventually agreed to pay indemnities to families of lynching victims if the victim was a Mexican national, beginning with Luis Moreno in California in 1895. After 1928, public lynchings would become rare. Among the Latino community, this history died down.

A History Lost

In his own research through numerous newspaper archive microfilm from 1849-1880, Ken Gonzales-Day has uncovered over 350 cases of lynchings of Latinos — 59 of which were in Los Angeles — by investigating incidents in the West that were previously reported as “white”.

His research also showed him that most Mexicans were lynched without due process and that lynching of Latinos were not taken as seriously as the murder of white people.

“Often they suffered quite terribly,” Gonzales-Day said. “Ropes would break in the middle, they might have to do it more than once. These were very brutal and very public ways of killing an individual … to inflict the most harm and send a message to the Latino community in those areas.”

The Equal Justice Initiative sponsored the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, which remembers Black lynching victims. While Latinos make up 10% of lynchings, Black people represent a much larger number. In 2005, Senate issued an apology to the victims of lynchings and their descendants for not enacting anti-lynching legislation, but Carrigan said it was mostly aimed at Black communities.

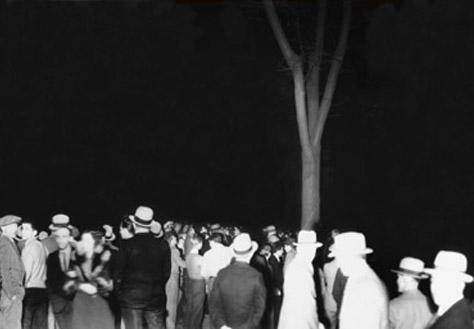

In 2006, to combat the narratives around the lynching of Latinos, Gonzales-Day created a an art series called “Erased Lynchings” where removes the victim and rope from historical photographs of the lynchings so the viewer can focus their attention on the violent, predominantly white mob left visible.

“‘The Erasure’ was about referencing the erasure of Latinos from local politics, historical memory, and also to draw attention to the construction of whiteness — to really get a chance to look at the crowd, to see their expressions, to see their gestures as they’re basically taking part in the murder, and yet they’re often quite happy,” Gonzales-Day said.

According to Gonzales-Day, there hasn’t been any type of acknowledgement or atonement for the state from the state of California about its racist legacy of lynching Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans.

To bring awareness, Gonzales-Day created a walking tour of the downtown lynching sites, which allows participants to walk through old Los Angeles and see unmarked sites where the ethnically motivated murders occurred.

“In some of these cases, these individuals were marginalized,” Gonzales-Day said. “First their land was taken, then the question of migration and immigration are part of it — who belongs and who doesn’t. Realizing that racialized violence is an American tradition might help all of us to better understand and rethink our relations to each other.”

The Fight for Recognition

Gonzales-Day and Beserra Núñez are part of an ongoing conversation about placing a Mexican American-Latino historical monument in Los Angeles to educate people of the history. The initiative started when Beserra Núñez first learned about L.A.’s legacy of lynching Mexican Americans through Gonzales-Day’s “Erased Lynching” exhibit. Moved by the history, Beserra Núñez invited Gonzales-Day to give a lecture at El Pueblo, and soon after, an ad hoc committee was created to advocate for a monument.

The El Pueblo commission has voted unanimously to support the creation of a Mexican American-Latino historical monument. They also have various letters of support from various activist groups and political leaders, including one from Garcetti himself, who also appointed Beserra Núñez to the group.

Now, with Beserra Núñez leading the ad hoc committee, they are meeting with various political and community leaders, meeting with potential funders, and developing a plan of action. They plan to present this idea to Mayor-elect Karen Bass and gain her support.

Beserra Núñez said that El Pueblo is working closely with the Chinese American community, who are giving them a lot of support for a Mexican American-Latino monument. According to Beserra Núñez, El Pueblo takes its inspiration to gather collectively and advocate from the Chinese American community, who recently lobbied for the new memorial to the victims of the 1871 Chinese Massacre in Los Angeles.

“Too often, we only gather and talk with people that we know, but we’re talking past people from other cultures,” Beserra Núñez said. “And so I think it's very important for us to have dialogue with people who are different from ourselves, to share our stories, and be able to support one another. Community support is really critical.”

In addition to the memorial, Beserra Núñez hopes for more recognition of these lynchings through having it incorporated into education. The state has required ethnic studies to be taught in the school, but not all of the schools have the curriculum and trained teachers to provide that information. She also hopes people will explore the history of Mexican Americans and Latinos on their own.