L.A. TACO is embarking on its biggest mission yet: to create a taco and food guide for every single neighborhood in Los Angeles! Along the way, we will also be releasing brief histories of each neighborhood to understand L.A.’s past and present a little more, all the while celebrating how each and every square inch helps makes our fine city the best in the world. Today we're taking a look at Koreatown!

Koreatown embodies everything we love about Los Angeles: a lively, rich, widely popular, and extremely walkable neighborhood that stands as a world of its own, named for the visionary new arrivals and their descendants who fought hard to forage it into the electric, eclectic cultural bastion representing Korean America that Angelenos flock to today.

Los Angeles County is blessed to have the highest population of Korean Americans in the nation, and this centrally-located neighborhood stands as an epicenter of Korean American family life; a monument to immigrant stories, resilience, and customs offering a parallel window into many of the Korean peninsula’s current pop culture, style, and dining trends, as well.

Few neighborhoods, and likely most cities, could consider competing with Koreatown over its sheer concentration of businesses; a massive medley of thousands that includes beloved spas, bars, pool halls, arcades, bakeries, gaming cafes, gyms, nightclubs, malls, media outlets, shops, salons, at least one axe-throwing pub and one semi-indoor rooftop golf course, and over 500 restaurants, all within its scant 2.7-miles.

This stretch of L.A.’s Mid-Wilshire may be a better place to take in Hollywood history than in nearby Hollywood itself. The neighborhood once housed such legends as the iconic, hat-shaped Brown Derby restaurant and the Ambassador Hotel, where the Academy Awards were held from 1930-1934 and where Robert Kennedy was assassinated more than 30 years later. The neighborhood’s golden age glamour continues to survive in a surfeit of buildings boasting beautiful architecture, like the Talmadge building, and preserved landmarks, such as Chapman Market, the gorgeous Art Deco-style, copper-topped Bullocks Wilshire building, and The Wiltern Theater, which was first opened briefly under Warner Brothers as a vaudeville theater, then reopened years later bearing the name we know today, inspired by its Wilshire/Western intersection. The Prince restaurant, which has a history stretching back to 1927, still frequently appears in T.V. and film when not serving crispy, sweet, and spicy, Korean-style fried chicken and cocktails to its fans.

While Dr. Philip Jaisohn was the first Korean-born person to become a naturalized citizen of the U.S. after arriving in 1885 as a political exile, KORE tells us that Koreatown’s official history begins with the immigration of hugely influential Korean independence activist, social and spiritual leader, educator, and advocate for Koreans living in the U.S., Ahn "Dosan" Chang-Ho and his wife, Yi Hye-ryon, to San Francisco in 1902. The next year, the first voyage of Koreans to immigrate to Hawaii for agricultural labor in sugar plantations was launched. Over the following years, more Koreans would venture to Southern California to find work on its farms or seeking educational opportunities. Dosan and his wife first moved to Riverside in 1903 then to Los Angeles in 1914. But he was not content to stick around sunny California, leaving his family behind and relocating to Shanghai as a minister in the newly formed Korean Provisional Government. There he helped lead actions against the occupying Japanese imperialist government, often being arrested and tortured along the way, after settling his family on Figueroa Street in Bunker Hill, where a Korean community had formed. He later founded The Korean Presbyterian Church on Jefferson Boulevard and Van Buren Place, which has been honored with the name Ahn Chang Ho Square, much like the similarly named Dosan Ahn Chang Ho Memorial Interchange, the official name of the 110 and 10 Freeway interchange. Many Korean newcomers would gather around the church, together helping to build a Korean neighborhood and community supported by stores, restaurants, and markets throughout the 1930s. In 1936, the hugely important Korean National Association, which was co-founded and lead by Dosan to fight Japanese occupation of Korea and advocate for the interests of Koreans, would transplant its main headquarters from San Francisco to L.A., helping increase the importance of our city to Korean immigrants as their populations increased.

Fierce discrimination was common against Koreans and others arrivals from Asia and their descendants. Until 1948, Racial Covenant Laws kept Koreans from living north of Adams, south of Slauson, west of Western, and east of Vermont. Once the Supreme Court struck those laws down, Korean Angelenos spread out north of Olympic Boulevard. In the 1950s, a wave of women and children came to the States from Korea following World War II, consisting of women who had married U.S. soldiers and children adopted into U.S. families. Even bigger waves of people moved to the States from Korea starting in 1967 after the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, that opened the doors of the country to more Asian immigration. Many Koreans in the area began taking advantage of declining property values in Mid-Wilshire in the late 1960s to acquire residences and start commercial businesses, setting the stage for Koreatown as we know it now. The Ahn family home is still maintained on the campus of USC.

Among these new arrivals in the late sixties was a businessman named Lee Hi Duk, credited with opening the Olympic Market for Korean groceries in 1968, back when the Korean population of Los Angeles hovered closer to 10,000, many of whom flocked to the store. Lee followed this by purchasing five blocks at Normandie and Olympic to create a dedicated Korean development known as VIP Plaza shopping center, next to his Young Bin Kwan (V.I.P. Restaurant), considered L.A.'s first Korean restaurant, which faithfully served as a community hub for celebrations and meetings. Lee, ever passionate about Korean culture, was a stalwart sponsor of cultural events, festivals, fashion shows, and the arts. Despite scant funding, lobbied Mayor Tom Bradley to create a dedicated Koreatown, resulting in official signage being installed in 1982. Read more about Koreatown pioneer Lee Hi Duk's life here.

In 1992, Korean Los Angeles landed in worldwide headlines as the Los Angeles Riots/Uprising, spurred by the acquittal of LAPD officers who had beaten up Rodney King on camera, laid bare the racial tensions some Black residents of South Los Angeles felt towards Korean business owners. The riots ignited just over 13 months since a Korean shopkeeper shot 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, an African-American girl, in the head for throwing a bottle of juice she was accused of stealing onto the store's floor, killing her. Beginning April 29, 1992, Korean businesses were routinely targeted, looted, and often burned over the next six days, leaving 63 dead, over 2,300 injured, over 12,000 arrested, and an estimated $1 billion in damages. Few will forget the sight of Korean shopkeepers, many of them war veterans seeking a quiet life in the U.S., and their children, staked out on the roofs of their stores with firearms, ready to defend their lives and livelihoods, in the paper and on the nightly news. In 1997, the nonprofit Korean American Coalition created the Alternative Dispute Resolution Center to help mediate divides between Black and Korean Los Angeles. More recently, we've seen groups like KTown For Black Lives appear. One lasting effect of all the carnage was seeing Koreatown's borders, famously ever-shifting even today, move slightly northward, where it thrives today, 20 years since so many lost so much.

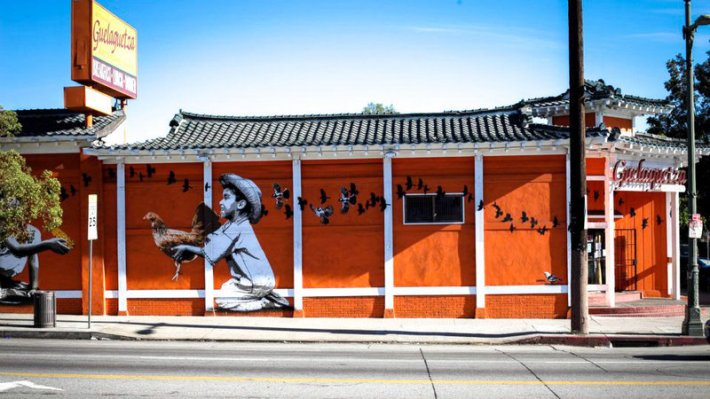

Despite the neighborhood’s iconic name, the census powers consider more than half of Koreatown residents " Latino. Two-thirds of the community is foreign-born, reflected in a diverse array of businesses and households. While Koreatown may be best known for its Korean barbecue, fine dining, traditional, funky eclecticism, and late-night restaurants, its dining scene remains diverse, including such local, widely admired favorites as Oaxacan Guelaguetza, Peruvian Pollo a la Brasa, El Riconcito Salvadoreno, and the Mexican-Korean-flavor-uniting Olivia, among the many beloved non-Korean restaurants. But wait, where are its best tacos? So glad you asked.

In the past decade, Koreatown has become one of L.A.'s most popular enclaves for visitors and locals alike. Its ascent has grown somewhat parallel to the worldwide popularity of Korean culture at large, with growing mainstream interest in the nation's music, art, and food trends quickly replicated on KTown’s streets. Koreatown is truly the L.A. neighborhood that doesn’t sleep, as its spas, clubs, and drinking dens thrum into the wee hours, welcoming Angelenos into a nocturnal world of entertainment, repose, raucous drinking, and enriching dining.