[dropcap size=big]D[/dropcap]rive up Atlantic Boulevard in East Los Angeles, and you’ll see a familiar urban landscape: auto mechanics, strip malls, restaurants. There are food trucks and street vendors lining block after block, selling to locals and people who walk by. But Atlantic Boulevard once had another layer to its community fabric. Starting in the 1950s, locals referred to Atlantic Boulevard as “the Latin Strip.” Known for its dancehalls, restaurants, and music venues, the Strip was a musical haven for the primarily Mexican-American community.

While the rare relics of the Latin Strip’s former glory are still around, such as the CVS that was once the Golden Gate Theater and the Kennedy Hall event space, most of the bars and restaurants clustered along the Latin Strip are gone. But the music and community that came out of the Strip left a strong cultural heritage that has inspired generations of East L.A. musicians.

A trip down the Latin Strip

My maternal grandmother, Virginia Garcia, a Roosevelt Rough Rider raised in the Aliso Village projects, remembers going out to the Latin Strip in the late 1950s, when she started dating my grandfather, a music lover. “The people that we hung out with said, ‘let’s go to the Latin Strip’ because those were the closest places around and without having to go to the westside,” she explains. In this case, the “westside” meant west of the L.A. River.

Locals from her generation agree that the Latin Strip spanned the Atlantic stretch between Whittier Boulevard and the Pomona Freeway. At the northern end of near Pomona Boulevard was Pancho’s Flamingo, where Puerto Rican-American sensation Tito Puente, “The King of Latin Music,” would play timbales. A block down near Beverly Boulevard, my grandmother remembers Club Boom Boom, one of her favorite spots.

“Usually we’d go to the Boom Boom or the [Club] Baion or Rudy’s Pasta House,” explains my grandma Virginia, when I asked about her typical night out on the Strip. Then, there were the after-hours spots. “After the clubs closed, we’d go to the Coral Room [a dive bar on Beverly Boulevard just off of Atlantic] to have coffee and listen to jazz because they didn’t sell liquor after two o’clock.” Or, they’d go for steak picado at Largo’s Mitote (407 South Atlantic), a popular Mexican restaurant with live music. “Everybody went there after the clubs; there were big lines outside.”

Halfway down the blog from Largo’s stands Kennedy Hall (451 Atlantic Boulevard), a staple event space for up and coming Chicano bands from East Los Angeles. The venue is still open today as an event space.

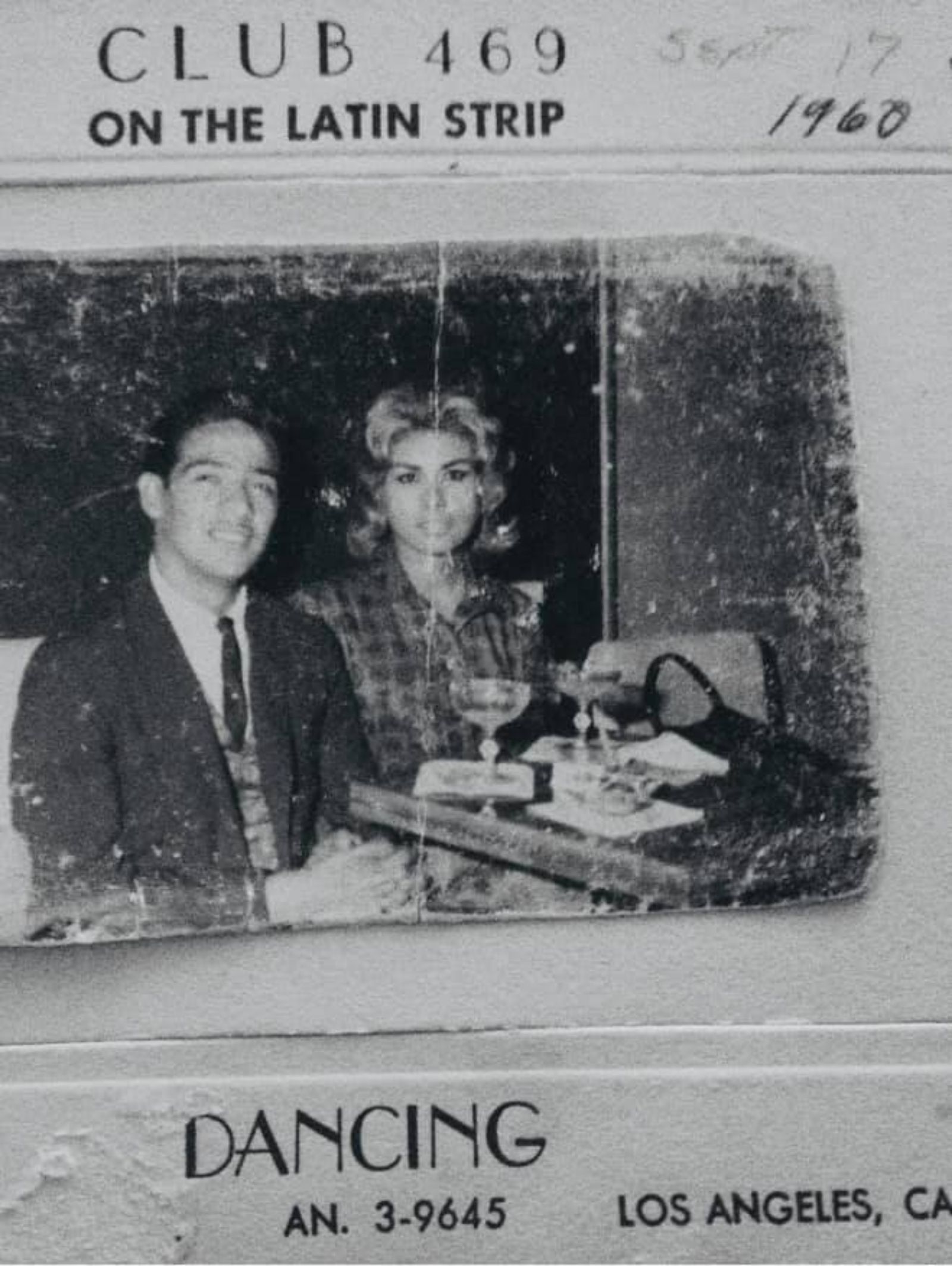

Today, pre-pandemic, La Rondalla Nite Club brings live Norteño bands and dancing to Atlantic Boulevard. But in that época (era), it was home to Club 469. Later in 1973, musician and “King of the Ch Cha Cha,” Manny Lopez purchased the club and dubbed it the Manny Lopez Club.

Another important element to the Latin Strip was the local Catholic Church, St Alphonsus. The church was instrumental in bringing the youth community together for organized dances that featured live music by local bands. After the dances, they’d continue their nights along the strip or for a late-night bite.

Down the street was a music venue called the Latin Strip (650 South Atlantic Boulevard), which later transformed into a now-defunct strip club, Pacheco’s Latin Strip. Today, it is the site of KIPP Raices Academy, an award-winning elementary school.

At the southern end of the strip, there was Club Baion, a nightclub owned by Josie Luján, my late grandfather’s cousin. According to my grandmother, the Baion had really good bands but pricey drinks. And just past Olympic, The Lampliter was a dive bar popular with young singles.

While not directly on the Latin Strip, East L.A. had numerous other noteworthy clubs that were popular around the same timeframe. Lalo’s Place, owned by legendary musician Lalo Guerrero, the father of Chicano music, was located on Brooklyn Avenue (now Cesar Chavez Avenue). At the same time, the M Club near 7th Street and Boyle was a favorite for after-hours jazz. And of course, The Paramount Ballroom, which opened in 1924, is one of the few living legends still around. Now, it is a pizza parlor.

Locals recall their favorite Latin Strip memories

Musician Mark Guerrero, son of Lalo Guerrero, recalls similar memories growing up in East L.A. in the early 1960s. Mark Guerrero remembers “the Strip” as a place for his father’s generation. He knew the entire East L.A. club and “Latin music” scene as the East L.A. Circuit. His teenage band, Mark and the Escorts, played the circuit and countless teenage venues and dances, held in church halls, event halls, and auditoriums spanning from downtown L.A. throughout East L.A. and further east as far as Pomona.

A lifelong musician and local music historian in his own right, Mark Guerrero remembers that the East L.A. music scene was so vibrant and active that it created the distinct Eastside sound. After getting his start playing East L.A.’s clubs and venues, Mark Guerrero built a successful music career and is a regular writer, podcaster, and lecturer on Chicano music. Today, he continues to interview Chicano musicians on his podcast and document their history through interviews, photography archives, and collaborations like A Great Day in East L.A. with photographer Piero F Giunti. In 2017, Mark and the Escorts’s music was included in the feature film Logan Lucky.

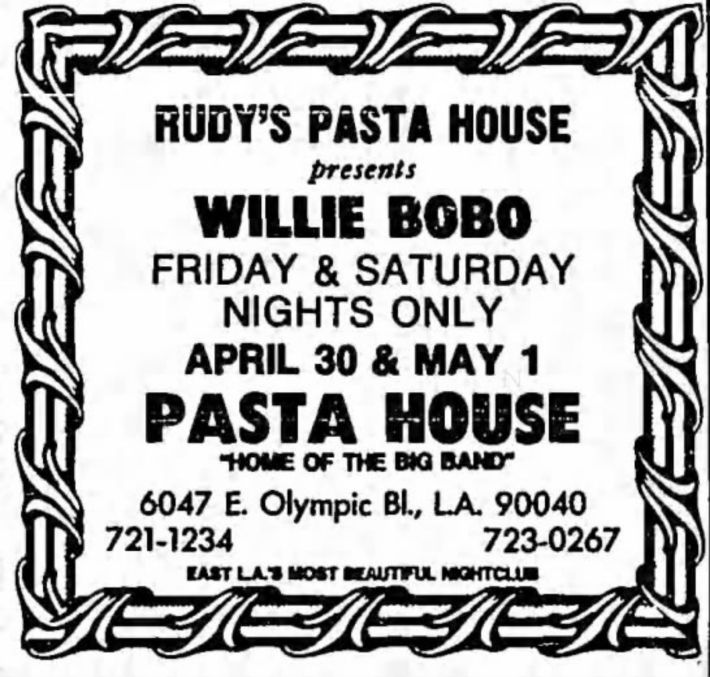

As the decades went on, the Latin Strip continued to transform. Graphic artist and resident Al Guerrero remembers the Latin Strip as part of his neighborhood landscape growing up in East L.A. off Whittier Boulevard and Kern Avenue. He recalls that there was something for everyone in East L.A., for the jazz fans, the cruisers, and then the disco and punk fans (He, too, has documented East L.A. culture on L.A. Eastside’s website under his alter ego, Al Desmadre). He remembers playing punk rock shows with his band at Rudy’s Pasta House, the same venue that once hosted jazz and cha cha cha musicians. “That whole Latin Strip thing, though it did die down, I'm gonna say, in the 90s, maybe, or late 80s,” says Al Guerrero.

When I connected with Vincent Lima, resident and former Rudy’s Pasta House bartender, he was surprised to hear me ask about the Latin Strip. “Interesting,” he says. “Not many people know about it, especially the younger generations.” As we spoke on the phone, he vividly painted a picture of the aging but vibrant Atlantic Boulevard that he grew up near during the late 70s early 80s. “The Latin Strip was always something that was there,” he says. Lima recalls a diner called the Chanticleer, a Chinese restaurant called Ho-Ho, and an Italian restaurant called Vesuvio. He also recalls Lincoln’s Fishbowl, a favorite watering hole, and two Mexican restaurants called Vivian’s and Cal-Mex.

Working at the Pasta House, Lima met numerous important musicians such as Willie Bobo, Tito Puente, Johnny Martinez, El Chicano, The Midnighters, and see other acts such as R&B group Bloodstone and War. Tierra was the house band on Fridays and Saturdays, and Los Lobos played on Sundays. “So it was like, you know, unbelievable. I got to meet all those guys. Serve them drinks, talk to them, and hear them perform while I was working as a bartender making money. ”

Today, the space is still there but no longer hosts concerts. Instead, Betty’s Pasta House is a beautiful event space for weddings, quinceañeras, and more.

While Hollywood had the Sunset Strip, East L.A. had the “Latin Strip”

The Latin Strip and surrounding bars and clubs represent a place where generations of young Mexican-Americans could express themselves freely in whatever language or musical style they pleased.

In his 2008 book, “Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935-1968,” Anthony Macías paints a picture that describes an East L.A. Mexican-American community stuck between a confusing mixture of racial discrimination and “a ‘frustrated assimilation’ where they were expected to conform yet didn’t reap the benefits of full access to society.” So they decided to create their own cultural expression and spaces. As Macías explains, the East L.A. community used music to cope with the struggles of living as second-class citizens.

My grandmother echoes this sentiment. “There was a lot of civil unrest and a lot of discrimination. They were very racist.” She appreciated the comfort and refuge of having bars and music venues for and by the community. “It was more comfortable. It was always more comfortable. There were mainly Latinos living in East L.A. at that time. I mean, the places that we went to were all mainly Latin, but it was like, as American as apple pie.”

Between the 1940s and the 1960s, East L.A. produced several talented musicians, due in no small part to strong music education programs in public schools. Musicians such as Chico Sesma and Don Totsi, a graduate of Roosevelt High School, were prominent musicians from East L.A. Musicians like Lalo Guerrero would open up their own clubs to be able to play what they wanted when they wanted. He opened Lalo’s Place in the early 1960s as a 400-person capacity nightclub. Today, his son Mark Guerrero laments, it is home to a strip mall home to four to five small businesses.

Meanwhile, during this same period, Hollywood was having a Latin Jazz moment. On West Hollywood’s Sunset Strip, affluent whites were entertained at Latin clubs by Latin jazz bands. The same Chicano musicians that didn’t feel particularly welcome in these same clubs as guests. Musicians such as Don Totsi and pianist Eddie Cano are two of many musicians who would play for both their East L.A. community and Hollywood audiences on the other side of the divided city. Perhaps the Latin Strip served as a community response to the need for culturally welcoming community spaces. When mainstream Hollywood had the Sunset Strip, East L.A. had the Latin Strip.

The local community keeps East L.A.’s musical history alive

One answer to keeping East L.A.’s musical history alive lies with community music education. LAMusArt, a BIPOC-led nonprofit that has been providing music education in Boyle Heights since 1945, is inspiring the next generation of musicians. Executive Director, Manuel Prieto, explains that their approach is making arts accessible to everyone.

One initiative they are currently working on is called the East L.A. Music History project. One significant component of this project is to create a 45-minute medley that will take listeners on a journey through East L.A.’s music history, featuring music from the 1940s, Lalo Guerrero and the 1950s Latin Jazz, 1960s brown-eyed soul, 1980s punk rock, Latin pop-rock, and current bands like Ozomatli and Quetzal. Dr. Isaac López, LAMusart teaching artist, composer, graduate of USC’s Music Performance program, will lead the project, which will also train advanced students to play and perform the piece.

Pre-COVID, they were planning to perform this piece at all the libraries in East L.A. and invite all the community (This portion will be on pause until it’s safe to gather). Then, they want to work with East L.A. libraries to curate all the music and history books so that people could check them out and learn more about local music history. Prieto hopes that LAMusArt students will perform the piece at East L.A. libraries by the fall of 2021.

“We want to make sure that this project not only speaks to students, but it also sparks a conversation between generations, so their parents and their grandparents. There's not a lot... [of] readily available archival information for the public, right? It's more available in publications from scholars,” explains Prieto. “I want the anecdotes to pass....between generations.”

“Our duty as a cultural institution is to really make sure that the entire community benefits,” says Prieto. LAMusArt hopes to inspire and educate their students and the entire East L.A. community on the area’s musical history.

What happened to the Latin Strip?

After a year of loss where the pandemic threatens to shutter our favorite bars, venues, and restaurants (or has already done so), it’s important to remember what we have already lost. Beyond many of them being family-run small businesses, we risk losing cultural hubs, community, and artistic output. East L.A. veteran ballroom, The Paramount, knows the risk and has been a vocal advocate for the #SaveOurStages movement. This movement successfully secured aid for independent venues and promoters in the latest COVID-19 Relief Bill.

So what happened to the once-bustling Latin Strip?

Change inevitably took over, especially in musical tastes and local demographics. Maturing populations moved further east into the San Gabriel Valley, Whittier, southeast L.A., and beyond to buy homes and start families. Lima suggests that younger generations perhaps didn’t want to carry on the family businesses, or ownership changes are the reasons for the Strip’s decline. Or maybe the proliferation of more clubs and venues off the Strip (such as Steven’s Steakhouse beyond the 5 freeway overpass in Commerce) attracted people with great live music and ample space.

What has replaced the Latin Strip? Physically, the area is still a vital artery that runs through the community. Strolling along Atlantic Boulevard on a Sunday afternoon, I encountered countless street vendors, food trucks, and street art. But what has replaced the music scene? Did it move to other community pockets, such as the East L.A. backyard punk concert scene? Did it move online?

Did the Latin Strip develop because there was so much natural musical talent within the East L.A. community? Or did the musical talent emerge because they had spaces to grow?

There’s no one reason for the disappearance of the Latin Strip or its surrounding bars and venues. But their absence has a lasting impact. In Land of a Thousand Dances: Land of a Thousand Dances: Chicano Rock 'n' Roll from Southern California, David Reyes and Tom Waldman argue that the lack of places to play in East L.A.—the dance halls, venues, ballrooms--has most likely hurt the number of artists and musicians coming out of East L.A. These spaces were critical to fomenting musical creation. Bands had opportunities to perform and grow their careers. While East L.A. still produces numerous talented musicians, maybe there would be even more if the vibrant Latin Strip was around today.

Maybe, East L.A.’s rich musical past and present are one of those inexplicable phenomena. Mark Guerrero explained it best. “It’s just like, why did the Renaissance happen in Italy? Or why did the grunge thing happen in Seattle? Why did the Beatles happen in Liverpool? There are places where there are just artistic or music booms, and they just happen. And, you know, East L.A.’s one of them, and it's never stopped.”