A cool breeze passes through the warm night as a classic Impala cruises by on the right, leaving lyrics from Cypress Hill’s "Insane in the Brain" stuck in your head for the rest of the evening. West Coast hip-hop echoes from the lot of Ruben Salazar Park and the sight of men in creased Dickies holding cans of spray paint lines Whittier Boulevard.

In the barrios of East L.A. lives a vibrant community of cholos, a Chicano subculture with a distinct and iconic style. Today, cholo culture is worldwide, and everybody wants in on their “stilo,” but the origins of this phenomenon often go overlooked. Most people don’t know that, as cool as custom lowriders and Nike Cortezes may look, this culture is born out of necessity.

Veteranos represented the culture in oversized suits, as the 1940s was a more formal era. The suits may have lost their shoulder pads and gained plaid patterns, but Latinos in L.A. have always rebelled, and their style was just one manifestation of their resistance.

Historical Context

One of the meanings that a Franciscan priest interpreted the Nahuatl word "xolo" to be was “slave” in colonial Mexico. But during the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s, Latinos in America reclaimed the term “cholo,” accompanying with it a fresh rebrand that would become the Chicano expression we now know for generations to come.

Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles quickly found ways to identify one another and create places for themselves to belong. This first happened with the Pachucos during the 1943 Zoot Suit Riots, a significant, five-day response to racial injustice in America’s history. Categorized by the Pachuco’s high-waisted, baggy pants and long, oversized coats, this flamboyant suit was more than a fashion statement.

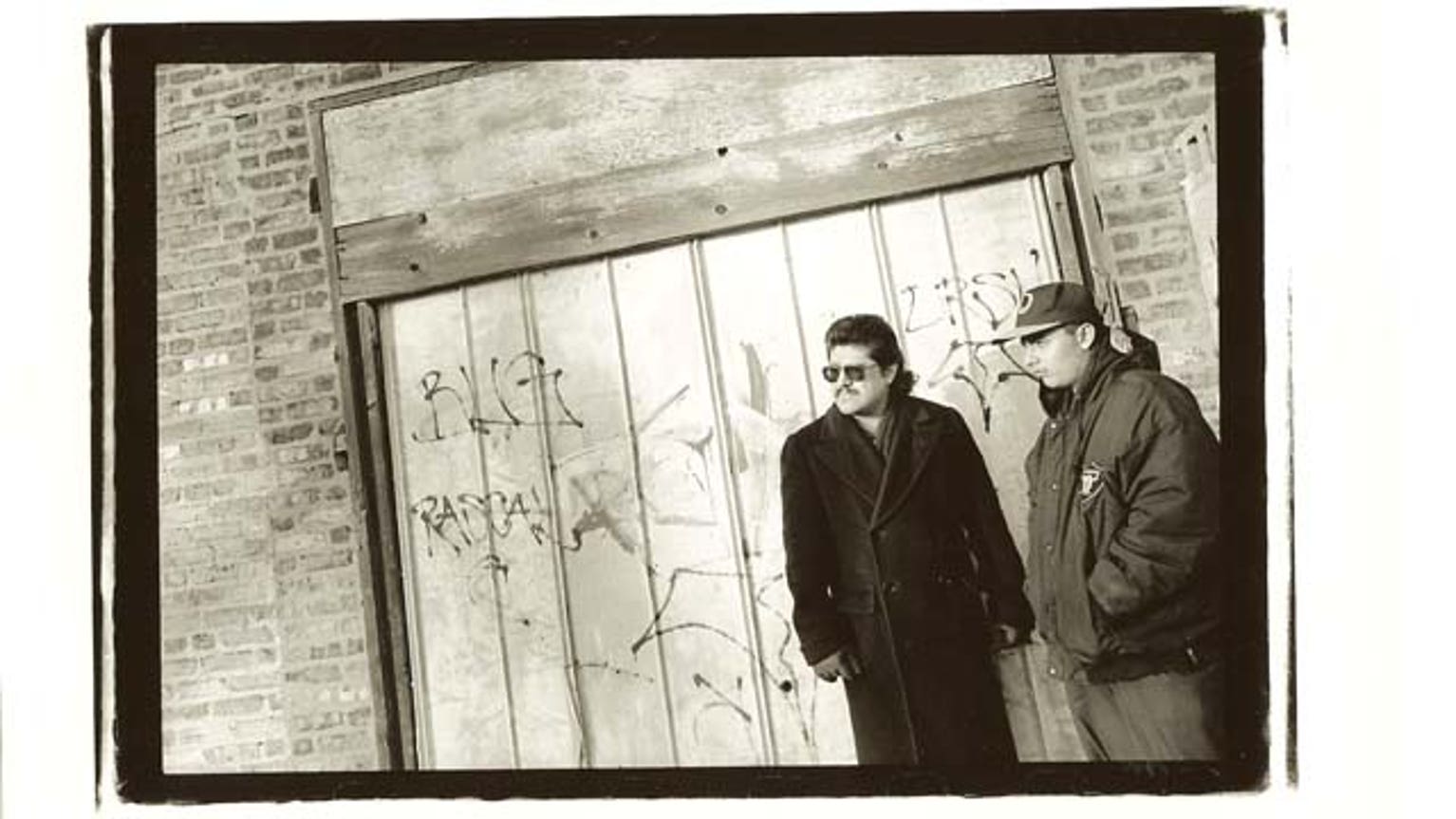

“Their style was impeccable,” street photographer Estevan Oriol tells L.A. TACO. “That’s one thing they made sure you couldn’t take from them. They always had style. From the zoot suit days with those ‘40s cars, to the Pendleton days, to this era.”

During the 1940s, clothing was conservative and minimal, especially during World War II amid America’s effort to ration fabric. Most men wore slim-fitting suits, while many Pachucos opted for the oversized garb, making a shocking, unpatriotic statement. The suit was used to stand out and reject societal expectations, something that became embedded in cholo culture.

One summer night in 1943, 12 white sailors were getting off a bus in Los Angeles, and a fight had broken out between them and a group of teenagers [Pachucos] in zoot suits. Although no one can say exactly what sparked the friction, a seaman emerged with a broken jaw.

“Searching parties of soldiers, sailors, and Marines hunted them out and drove them into the open like bird dogs flushing quail,” author Seldon Cowles Menefee wrote in his travelog, “Assignment U.S.A.”. “Zoot-suits smoldered in the ashes of street bonfires where grimly methodical tank forces of servicemen had tossed them.”

LAPD officers stood by, and Al Waxman, editor of East L.A. newspaper The Eastside Journal, reportedly begged them to intervene. But they refused, calling it “a matter for the military police.”

Violence grew for days until the Western Defense Command drew a line in the sand, declaring Los Angeles off-limits to soldiers, sailors, and Marines, ordering police to arrest unruly servicemembers. Additionally, the Los Angeles City Council banned zoot suits, and by the end of it, nearly 600 were arrested, while few white servicemen were ever charged.

“Today’s cholos were an evolution of the Pachucos,” 70-year-old activist and writer Luis Javier Rodriguez said. “But by the 60s, it was a whole new style. I think it was our resistance. It was a resistance to not being assimilated in America, but also not being Mexican because we weren’t really Mexican anymore. We created a third way of being.”

The Aesthetics

Their aesthetics are undeniably fly, inspiring streetwear everywhere. In Japan, it’s no longer an oddity to see a man with his hair slicked back, leaning against a lowrider wearing creased Dickies, and an oversized Pendleton flannel buttoned only at the top.

“When I started dressing myself and going through my wannabe stages, my dad woke me up at 5 AM to make sure that I creased my Dickies,” comedian Frankie Quiñones told L.A. TACO. “My mom didn’t like it, but Dad said, ‘I’m going to teach him. He needs to learn.’”

From taking him cruising in his 1965 Impala, which featured a chain steering wheel, to teaching him the importance of hard work, Quiñones’s father, like those of many Latino Angelenos, has inspired him in his personal vibe.

“I got a ‘65 that’s getting worked on to pay homage to my father who had one,” Quiñones shared. “And my Nino, my godfather, has a ‘39 Plymouth Bomb, two-tone—a cream color and lime green, which I know sounds like it doesn’t look good, but it looks clean.”

For many Chicanos, lowriding goes beyond a vehicle to become a lifestyle. It’s about taking something old and discarded and making it yours to show the world.

They did the same with their neighborhoods. If you cruise into East L.A., you’ll quickly find street art featuring designs of roses, chains, and hearts, elaborate calligraphy like Old English Script, and even religious symbols, particularly “Our Lady of Guadalupe” (La Virgen de Guadalupe).

“Our people always made sure that something looks beautiful,” Rodriguez tells L.A. TACO. “The Pachucos took zoot suits from Harlem, but they made ‘em more garish. They actually embellished them.”

Rodriguez was painting graffiti on the streets of Los Angeles when a mentor asked him if he’d given though to muralism. While his street art was intricate, he hadn’t yet considered himself an artist until the mentor handed him a book about 1970 Mexican murals. Young Rodriguez carefully examined each page, taking in work from activists like Orozco Rivera. Upon completing the final page, its rear cover made a lasting impression—an image of the Mayan temples spoke to his spirit.

A youth gang member at the time, Rodriguez thought he was just having fun breaking the law. But he learned a profound lesson within the covers of that artbook—what he was doing had been practiced by his ancestors.

“Nobody ever told me that it’s in my blood,” Rodriguez said. “I was always somebody you could dismiss, ‘this guy is nothing.’ But my mentor planted a seed. At 17, I painted 10 murals with 13 gang kids. It helped save me and helped a lot of kids… We need to know this stuff, it’s in our heritage. We need to know who we are.”

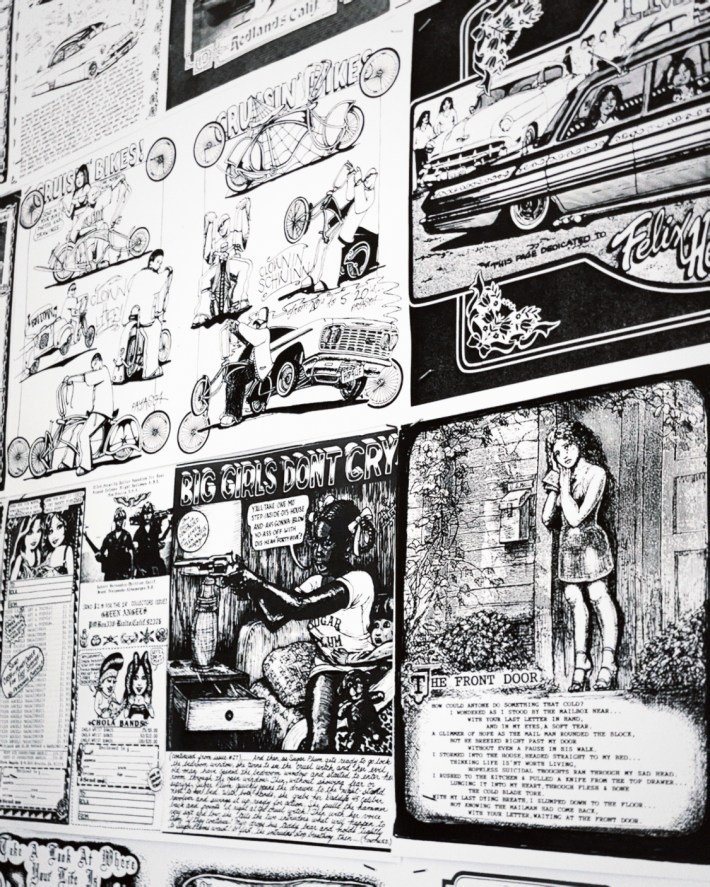

Oriol’s exhibit, “Dedicated to You” at “Beyond the Streets,” tells important tales through artistic compositions by himself, the late David Holland (famously known as “Teen Angel”), and other individuals from the community.

He intended for the exhibit to be a true homage to Holland, in honor of his contributions to the community, through his artwork and magazine, “Teen Angel.” The publication’s first issue released in 1981 and ran until 2006, celebrating Pachuco culture in all of its chainlink glory.

As groundbreaking works-of-art go, his cultural celebration wasn’t without controversy. Despite the magazine regularly printing anti-violence and anti-drug slogans, authorities accused “Teen Angel” of glorifying the violent gang lifestyle.

In 1992, the Los Angeles Times reported that law enforcement officials were using it in training courses and lectures as a guide to identify trends and graffiti pseudonyms. Despite it being considered “The Voice of the Varrio,” most mainstream retailers didn’t carry “Teen Angel,” and it was even banned in some correctional facilities.

This authentic representation of culture showcased real stories of people in the community, sharing letters from readers to their loved ones, coloring book pages, and even obituaries. Of course, the publication discussed gang violence and drug use, but the story of the Chicano struggle cannot be adequately told while dancing around the tragically true stories of the barrios.

Core Values and Identity

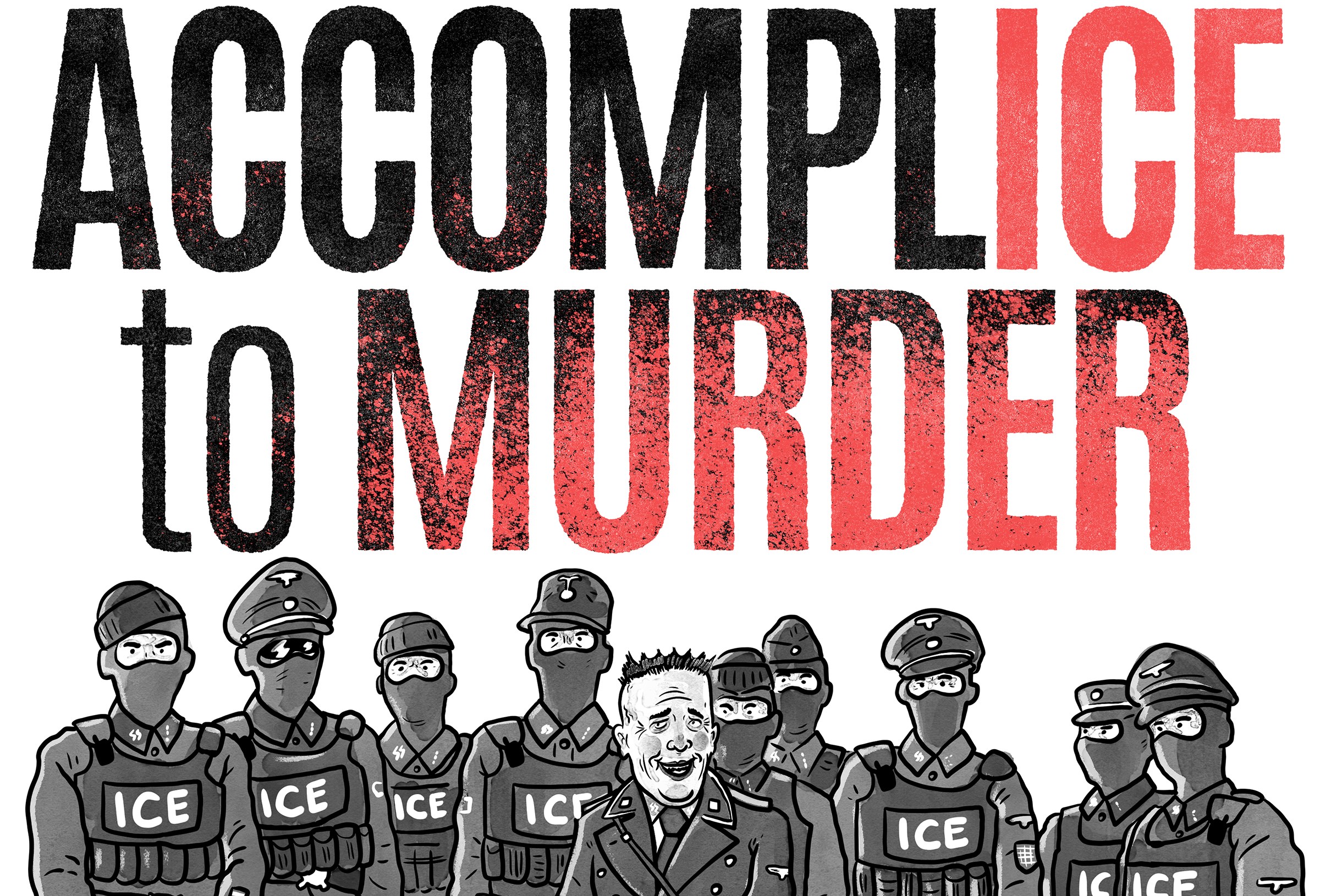

Despite street culture playing a significant role in the movement, it carries a complexity that can’t be ignored. While there are culturally rich values embedded within, such as respect, loyalty, and family, these same values have also been co-opted by groups like the first prison gang, La Eme (the Mexican Mafia), which formed in 1957. Though La Eme emphasizes principles like respect and family, it has also built a reputation for violence and criminality. The duality of this culture, where both resilience and hardship coexist, is reflective of the Chicano struggle itself: fighting for dignity and identity while confronting the harsh realities of gang violence and systemic oppression.

“My dad, he was a good dad, man, always driving me to little league practice,” Quiñones said. “He had a ‘65 GMC truck—you know, the sidestep ones—and we’d just be low riding, just looking at me, ‘Hey, Mijo, work hard for people to get respect.’ That's the big reason why I owe a lot of my success to my parents.”

Rodriguez joined a gang at 11 years old and developed a drug addiction shortly afterward. At 16 years old, he found himself on Murderer’s Row, next to Charles Manson for a crime he didn’t commit during the 1970 East LA Riots.

“They let us, cholos, sit for several days and nights,” he recalls. “There were five of us and we disappeared. Nobody could find us. My family couldn’t find me.”

After long days and nights behind cold bars, footage surfaced that showed Los Angeles Police officers committing the murder Rodriguez was accused of.

His harrowing experience as a child highlights the systemic injustices faced by Chicanos, where wrongful incarceration and racial profiling are all too common. But beyond the confines of prison walls, life for many took unexpected turns—some rose above the challenges, while others were pulled deeper into struggle.

“I like to hear how the guy ended up in a tent on Skid Row and how another guy ended up with a mansion in The Hills,” Oriol told us. “Besides, I’ve met plenty of shady people that weren’t in a Mexican or Black gang that were scumbags - the f***ing worst of the worst.”

“The more you criminalize it, the more you end up making gangs and criminals out of people,” Rodrigues said. “It really was a resistance to being assimilated, to having your own voice, your own story.”

Similarly, Quiñones emphasizes that the formerly-incarcerated are often unfairly vilified.

“Believe me, some of the guys I know that did time in prison are some of the nicest guys,” he said.

He remembers the day his mom met his friend Danny. They were barbecuing at her house, and she had only good things to say about him.

“Oh Mijo, Danny is so nice,” Quiñones recalls. “But then the next day, he was in a high-speed chase and sideswiped five cars. They put a shotgun to his head, and mom couldn’t believe it. But, he’s out now, and he’s doing good.”

As seen throughout history, racial injustice enables the cradle-to-prison pipeline. In the Pachucos’ case, what was once their response to injustice was used against them for the racist’ agenda. Like the Zoot-Suiters, a contemporary and common misconception is that people representing cholo-style are savages. The truth is often far from that.

“The more you criminalize it, the more you end up making gangs and criminals out of people,” Rodrigues said. “It really was a resistance to being assimilated, to having your own voice, your own story.”

Impact on Pop Culture

It might sound strange to hear that the Japanese in Tokyo are championing cholo vibras. Perhaps stranger is their presence in Germany, where Latinos comprise less than 0.05% of the population.

Oriol’s role in Chicano culture is essential when considering its international impact. The L.A.-native found himself in the world of hip hop, working as a bouncer along with tour-managing the legendary groups, Cypress Hill and House of Pain.

While on the road, Oriol showed the world what was happening on Skid Row and in East L.A.

“People here in my culture weren’t letting me in,” he said. “They just shut the door on me. So, because I had the reach from touring with Cypress Hill and meeting magazines, I started sending my photos to put my stuff in German magazines or Japan or whatever. I was published there because I had something that they couldn’t get and they loved it.”

Another significant turning-point in the trendification of this culture was the union of Oriol and the iconic artist, Mark Machado - more widely known as “Mister Cartoon.” Following their meeting at an album release party in 1992, this brotherhood became a partnership, utilizing one another’s skills and networks.

Oriol invited Machado to tour with him and Cypress Hill, and commissioned him to design an album cover for the group. Machado’s work became recognized for his clothing designs and murals on the hoods of lowriders in Japan, his artistry captured by Oriol for local magazines, rewarding him a few extra hundred bucks for images of the cars. These Chicanos brought lowriding culture to Tokyo.

It wasn’t long before the duo put together a homemade tattoo gun. Oriol recommended Machado’s ink to Cypress Hill members and other co-headlining tour acts such as Goodie Mob and Outkast.

Five years later, with the same homemade tattoo machine, Machado had a milestone appointment doing Eminem’s tattoos, a portrait of his daughter Hallie, and the " R.I.P.” for his uncle. His reputation was cemented, and before he knew it, international stars would be tatted with black-and-gray realism. Beyoncé even has a praying angel symbol on her left hip.

Cholo culture had left the barrio.

The Modern Face of Cholo Culture

While Chicanos inspired the aesthetics in gangs and prisons, the look has evolved and been given a new life. Today’s world is different from the one that the Pachucos roamed or even the one that the O.G.s remember. Germans don’t need to read a local magazine to learn about the cholos because it’s on their phones in many different forms.

An Italian can stumble upon Oriol’s famous “L.A. Fingers” image on an H&M crop top, or one of Quiñones’s “Cholo Fit Creeper” skits on Instagram. Rodriguez’s books can be bought in a digital format, and the city that once outlawed zoot suits saw Justin Beiber bring the style back on its Grammy red carpet.

Another aspect of modern society concerns the widely discussed topic of “cultural appropriation.” Latin Americans' ancestors endured enough colonization to last a lifetime, so it’s important to distinguish robbery from inspiration.

“People are telling me like, ‘Hey, you showed all those Asians our culture, and now they’re tattooing it on them,’” Oriol said. “First off, how many people rock Asian-inspired tattoos like their letters and the fish? Besides, the way they look is how we used to look. They have the same haircuts, and their cars are just as low and slow. How cool is that?”

Not to mention, the Chicano style resonated with refugees and immigrants like the Cambodians and Armenians as well.

“I think it was the style that best spoke to their own traumas from war, from being in a new country, from killing fields,” Rodriguez theorized. “They were all coming from rough places and incorporated the style that really spoke to the trauma.”

The top-buttoned flannels are an evolution of the gigantic blazer, and Dickies, the modern suit pants. What the uniforms represent are the same. The only differences? The evolving battlefield and armor.

While “Chicano” specifically refers to Mexican Americans, in the context of racial injustice in America—particularly in East LA—Latinos of various backgrounds were often treated as a single group, facing shared struggles and marginalization.

Latinos have led movements of resistance for centuries, and their style reflects that—activism pulses through their veins, as it did with the creativity of Aztec muralists.

Pachucos clashed with American ideals during WWII and in 1968, Chicano students led the East L.A. Walkouts to protest discrimination at schools. Soon after, César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and the Brown Berets fought for farmworkers' rights during the Chicano Movement.

At 16, Rodriguez was unjustly incarcerated during the Chicano Moratorium Riots, protesting the high number of Chicano soldiers sent to Vietnam. Meanwhile, movements led by the likes of the Zapatistas in Mexico and the Sandinistas in Nicaragua waged their own battles.

Latinos have led resistance movements for centuries, and their style reflects that—activism pulses through their veins, as it did with the creativity of Aztec muralists.

Ultimately, Cholos embody survival—surviving the prejudice of the 40s, the broken school system, the injustice of the courts, the military draft, the prison pipeline, and the unforgiving streets. Latinos have been a part of United States history for centuries and will continue to fight for recognition and dignity—and they’ll do it in style.