“Sweeps,” or sanitation cleanings, as they’re sometimes called, are supposed to keep our city sidewalks clean and help move people living on the streets indoors. But according to new data obtained by L.A. TACO from the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA), the lead agency responsible for homeless housing and services in the city, few unhoused people have been sheltered as a result of outreach associated with the encampment clearings seen regularly across the city (also known as “CARE cleanings”).

And almost nobody has been moved into permanent supportive housing.

“I don't know how many times that they’ve came and taken down my information,” said La Donna, an unhoused woman living near an electrical substation in an industrial part of the San Fernando Valley, during an interview last month. “And nothing has come from it.”

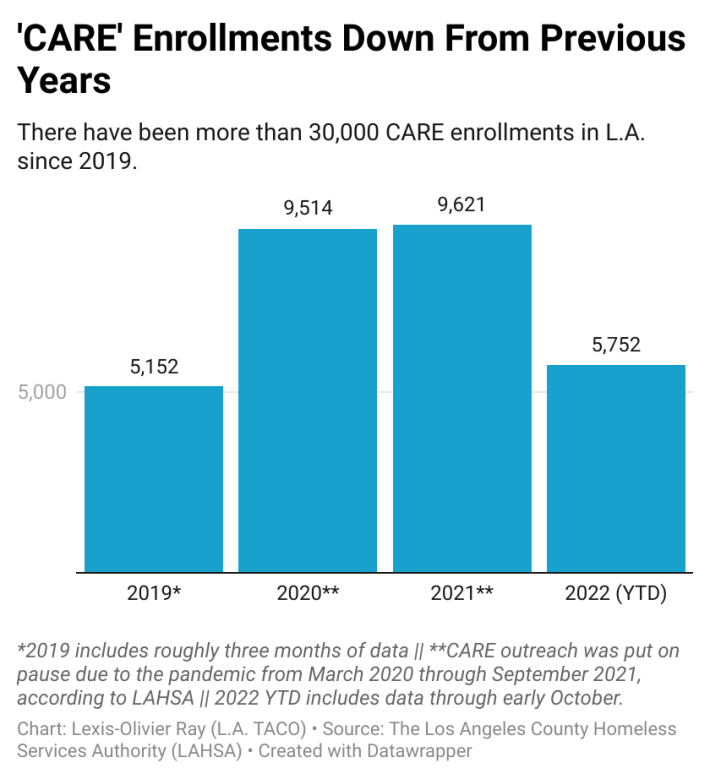

Since 2019 more than 30,000 unhoused residents, like La Donna, have been “enrolled” in the CARE outreach program according to LAHSA’s data. That’s roughly ten thousand fewer people than the total number of unhoused residents currently living in the City of Los Angeles.

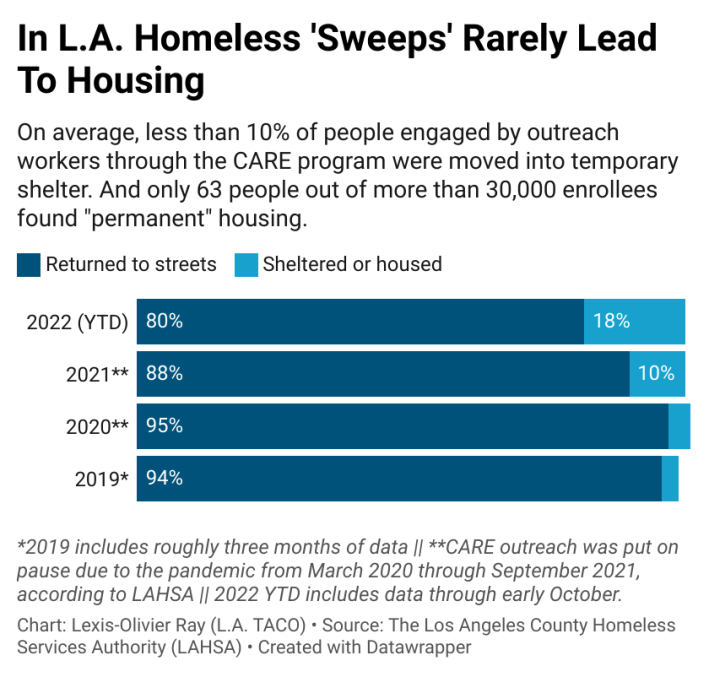

Less than 10 percent of those 30,000 “enrollees” moved into a temporary housing facility.

And fewer than one percent (or 63 people) moved into a place categorized as “permanent supportive housing," according to LAHSA’s data.

On average, about nine out of ten people that CARE outreach workers encountered resulted in folks returning to settings not meant for habitation or “no exit interview completed.” In other words, outreach workers lost contact with the vast majority of their clients and they likely remained on the streets.

The data comes from LAHSA's Homeless Management Information System (HMIS), a federally mandated database that tracks services provided to unhoused residents. The data shows how many people ended up in permanent supportive housing and temporary shelters as well as the number of people who died or wound up in a hospital or a treatment facility while enrolled in the CARE program (from the fall of 2019 through September of this year). Due to the pandemic, CARE outreach was limited to “[informing] clients about COVID” and passing out personal protective equipment from around March 2020 until September 2021, according to a spokesperson for LAHSA. The spokesperson declined to comment further on our findings.

La Donna laughs at the idea of being “enrolled” in the CARE program, or “CARE-sus” as she and her unhoused neighbors call it (rather than CARE+). “I don't know what kind of database that they're putting [my information] in. But it's not for me to get any resources. It's not for anybody to contact me,” said La Donna. “That’s for f*cking sure.”

‘Who decides who gets on that bus?’

For two years John desperately tried to get off the streets but "something always falls through the cracks," the 55-year-old said in March, standing with his life' possessions by his side on the corner of Schrader Boulevard and Selma Avenue in Hollywood, while police officers and sanitation workers broke up the remaining pieces of what was once a sprawling homeless encampment.

Earlier in the week, during another encampment clearing on the same block, John spent time packing up his belongings thinking he would finally be transported to a hotel. But as he waited to board a bus, with several other unhoused residents, he received the devastating news that there was suddenly no room for him.

John spent that lonely evening in a parking lot in Hollywood defecating himself, a symptom of living without HIV medication for more than two weeks on top of not having access to a bathroom, he said. The next day he took his first shower in two months. “I didn’t care about none of my stuff, I raced into that shower,” he said.

John’s in Hollywood because he heard that “everybody is getting housing” as a result of the massive multi day encampment cleaning. But he’s been promised housing so many times and let down, he’s lost faith in the system.

“Who decides who gets on that bus?” he wondered.

Launched in the fall of 2019, after years of protests and lawsuits demanding change, the Cleaning and Rapid Engagement (CARE) program was intended to be a “services-led” approach to cleaning encampments rather than a system built on complaints and enforcement by police.

Since then, city officials have defended the controversial encampment clearings claiming they not only keep our city’s sidewalks clean, they also help move people living on the streets indoors. During Garcetti’s final “state of the city” speech earlier this year for instance, the mayor stated that CARE teams will provide “badly needed services to our folks in encampments,” and facilitate “their move towards housing.”

But experiences like John’s and La Donna’s as well as LAHSA’s data shows that’s not usually the case.

Rather than move people indoors, more than 15 unhoused residents and advocates interviewed for this story over the past nine months, said that CARE cleanings (or “sweeps” as they are sometimes called) push people with nowhere to go from one block to another. They’ve triggered medical emergencies and left people with serious chronic health conditions on the streets to fend for themselves. Plus they separate unhoused people from important belongings and resources.

“We gotta grab what we think is important but you can’t always get everything,” said Jacob, an unhoused man living near MacArthur Park, after the encampment where he was living was cleared in late-May. “We're losing shoes, we're losing the majority of our clothes, sometimes we lose money, a lot of times we lose our phones and electronics and things like that,” the 24-year-old said, “It takes a lot to start over, you know?”

Jacob said the sweeps have been so “stressful” he’s stopped caring about material belongings. “I just got it in my head like material items don’t matter out here.”

An unhoused man who just got off work was unable to breakdown their tent or save any of their belongings before sanitation workers threw everything into a trash compactor, this morning in Westlake. They arrived just after the sidewalk was blocked off. @LATACO pic.twitter.com/nGwKNaJA3D

— Lexis-Olivier Ray (@ShotOn35mm) May 24, 2022

“It’s like you come home from work and the house you’ve lived in for years has burned down and you have nothing now,” explained an outreach worker who was interviewed for a University of California San Francisco study on the health impacts of encampment sweeps from the perspective of healthcare workers. “All your memories and everything that is near and dear to you is gone.”

The study found that losing belongings to sweeps can have a direct impact on unhoused residents' health. Not only can they lose medical supplies like naloxone, prescription meds, and equipment such as walkers. They also risk losing sentimental belongings like photos and things from their childhood that often can’t be replaced and are tough to part with.

“I lost my whole entire military file,” said Cookie, an unhoused resident living on the border of a wealthy westside neighborhood and the City of Los Angeles, in June. “Everything that shows I served in the military is gone, and I can't replace it.” On top of that, she’s also lost computers, countless phones and some “irreplaceable” personal things that her grandparents gave her.

Cookie comes from a prestigious military family and for more than a decade served as a US Marine before a knee injury ended her career. “I fought for this country and I'll be damned, I'll be damned if I’m gonna let somebody else tell me what to do,” she said. “I have the right to make sure that my stuff is safe. And that I can have a place where I can lay my head”

Cookie suffers from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), an inflammatory lung condition that obstructs her breathing, as well as a lung lesion. “And I've been out here during the whole pandemic,” she said. She hopes a Section 8 voucher will bring her indoors soon. “I see everybody else getting it, but not me.”

Cookie is one of several unhoused residents that L.A. TACO spoke to who’ve endured sweeps while suffering from chronic health conditions.

In Van Nuys, we heard from La Donna’s neighbor, Tania, the mother of a 21-year-old son who suffers from uncontrolled seizures as well as the wife of a husband living in a tent on the sidewalk with skin cancer. “[My husband] has no use of his left eye,” Tania said during an interview last month. “It is slowly dying in his head.”

In February of last year, Tania’s son had a seizure during an encampment clearing. “He seized right here on the sidewalk in front of sanitation with no one around him,” Tania said pointing to the ground in front of her. “I didn't do anything to cause him to have a seizure. My husband didn't do anything to cause him to have a seizure. Yet for some reason we were blamed for his seizure.” Tania believes the stress and anxiety associated with the “sweep” caused the medical emergency.

Tania said offers of adequate housing don't happen before or during sweeps anymore. “What they mean [when they say outreach and engagement] is LAHSA drives down our street. That's it. They don't stop. They don't get out. They don't talk to us anymore.”

Sanitation workers discard a tent, bikes, tarps, chairs, shopping carts, tools, recording equipment and other belongings at an encampment in Westlake. @LATACO pic.twitter.com/6mOUZDmdDf

— Lexis-Olivier Ray (@ShotOn35mm) May 17, 2022

In a general statement, Elena Stern, public information officer for the Los Angeles Department of Sanitation (LASAN) said, "The role of LASAN with the CARE/+ program is to provide sanitation and hygiene services. Our partners at LAHSA provide housing services. It is our responsibility to ensure that the public right of ways are safe and clean for all — for pedestrians, residents, customers, businessowners and those experiencing homelessness. When we provide comprehensive cleanings, our crews are trained to identify and remove hazardous or contaminated materials for the health and safety of the public. Remaining personal belongings are bagged, tagged and stored, with information left on location about how to retrieve personal belongings. Our teams are trained and expected to exercise courtesy, respect, and compassion."

LAHSA’s data and the experiences of unhoused residents interviewed for this story, calls into question the success of a program that has cost taxpayers more than $150 million in salaries and expenses. Despite the substantial investment, there are more tents, vehicles and makeshift shelters seen on our city sidewalks and streets than ever before. According to LAHSA’s most recent homeless count, “visible homelessness” has grown by more than 15 percent since the pandemic started.

When presented with our findings, a spokesperson for Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office disputed our analysis of LAHSA’s data without evidence to support their claims. Weeks later, Jose Ramirez, Deputy Mayor for City Homelessness Initiatives, said in a statement: “When CARE+ outreach went offline from March 2020 to September 2021 to align with CDC guidance during the pandemic, the City and LAHSA shifted efforts to house Angelenos through Project Roomkey, which brought in more than 10,000 Angelenos and resulted in over 4,400 permanent housing placements.”

Ahmad Chapman, spokesperson for LAHSA, clarified that “During the time period above, the teams funded for CARE and CARE+ outreach continued to conduct outreach, but not for the CARE and CARE+ programs. During the pandemic's early days, we had all outreach teams working to inform clients about COVID, ways people could stay safe, and distributing personal protective equipment. As a result, CARE and CARE+ did not operate as originally designed, but outreach in some form continued.”

“This is the first year that CARE+ outreach efforts have lasted longer than six months,” Ramirez said. “And as a result, we’re seeing that our services-led approach is continuing to produce better results: in just seven months, we housed over a thousand Angelenos through this program alone.”

So far, enrollments this year are down nearly 50 percent from the previous years, according to LAHSA’s data. And roughly 80 percent of enrollments have resulted in outreach workers losing contact with clients. But the number of people being sheltered through the CARE program in temporary facilities has increased, as more interim housing has been built across the city. From around 420 people in 2020 to just over 1,000 people through September of this year.

Molly Rysman, Chief Programs Officer for LAHSA, said the biggest issue that the system is facing is not having enough permanent supportive housing, during an interview with L.A. TACO this summer. “What we're seeing in our data is that when we move people into interim housing, they're getting stuck there,” Rsyman explained. “They're spending extraordinary amounts of time in interim housing because they can't get that permanent housing resource they need to get out of interim housing. And so our beds are being filled with people who are staying there month after month after month.” And therefore, there often aren’t any beds to offer to people living on the streets.

Rysman added that although investments into interim housing have been made, they haven’t been made consistently across the region.“And so there's some parts of the city where it's not that hard to get an interim housing bed. And then there's other parts of the county where it's extraordinarily hard.”

Rysman as well as other homeless outreach workers and volunteers who spoke to L.A. TACO for this investigative report all stressed that bringing people indoors is a delicate and complicated process. One that takes ample time, commitment and trust.

“Everyone's situation is so monumentally different,” Danielle Hampton, Director of Operations for Noho Home Alliance, told L.A. TACO during an interview in North Hollywood. Hampton has more than a decade of experience running shelters in Skid Row and now oversees operations for Noho Home Alliance, a homeless outreach group that spent months successfully transitioning a sprawling encampment in North Hollywood to a hotel earlier this year. “There is no one size fits all solution,” Hampton said. “People may need the same thing at the end of the day, but the pathway to get there is always going to be different and the willingness to follow that pathway is going to be different too.”

This story is part of an investigative series centered on homelessness and health for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 California Impact Fund.