[dropcap size=big]G[/dropcap]eorge Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony Mcdade, and Dijon Kizzee.

The deaths of Black people by law enforcement in the last several months have ignited a widespread Black Liberation Movement, and Black reporters across this country are speaking out about current and past struggles in newsrooms to cover the movement truthfully.

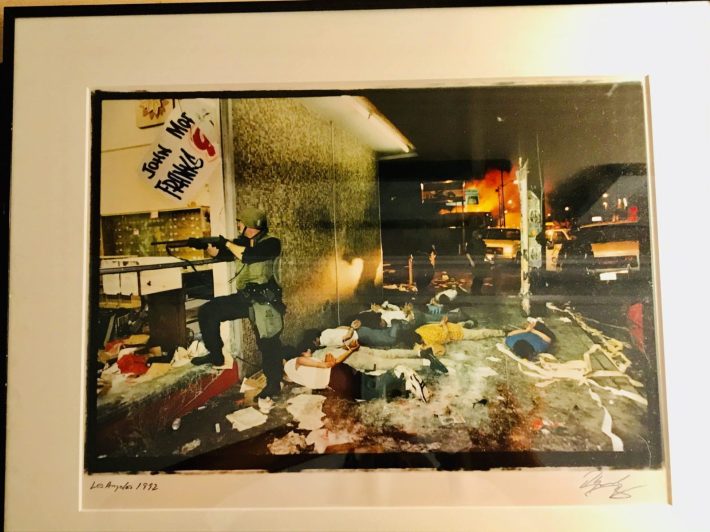

As protests continue every day in L.A, many veteran journalists found themselves hearkening back to the challenges of reporting on the 1992 riots and what they think should be done differently this time around.

Time Capsule: The 90s

Sylvester Monroe, USC Annenberg Senior Fellow, was a correspondent for Time. For the first 36 hours, he was the only reporter for his publication on the riots’ streets.

“The verdict was the fuse, and it had been simmering for years,” he said. He understood the protesters' anger. It was frustrating having White colleagues in the newsroom who couldn't recognize why Black people and other people of color were protesting the systemic injustices every day. In June, Monroe wrote in the Centre for Health Journalism: “I wanted to scream at my bosses. Just as the people demonstrating in the streets felt their cries for police reform and justice had fallen on deaf ears, I wanted to scream at my bosses who had not been listening to me. I wanted to scream the frustration of being a Black reporter and having to bury my personal feelings [ …] But I was a Time correspondent, and I could not.”

‘We got in the car, drove right into L.A., and by then, everything was on fire.’

Amy Alexander, author, and journalist says that when she saw the protests erupt on the streets in June, she was immediately transported back to that historic moment. Alexander followed the Rodney King trial very closely as a young reporter, three hours away from L.A at The Fresno Bee. Shortly after all the police officers were acquitted, she pitched her editor and headed to cover the story with two other colleagues that same evening.

“We got in the car, drove right into L.A., and by then, everything was on fire. People were literally setting fire to buildings. It was the craziest thing,” she said. The riots were almost purely spontaneous. “Now, there's a whole sort of universe of change that was born during the past 25 years, partly in response to these police cases and blatant abuses of power,” she said.

Reporting While Black in L.A.

For six days, Alexander reported on the anger and fear felt by Angelenos. “I'd never seen anything like that. It was unbelievable.” There wasn’t a prominent police presence for the first couple of days, and Alexander saw the chaos firsthand. “They were apparently told to stand down. So, it was like a free for all,” she said.

In many cases, Black journalists on the frontlines were the only ones who had access to protestors on the ground. When the protests started in South Central, the residents didn’t talk to White reporters as much. “It was dangerous,” said Monroe. “Anybody who looked White was being attacked.”

“I saw a White cameraman from a local news team get pushed around, and they were chasing him. I've never found out what happened to him. They were not happy to be seeing journalists, but they let me do my work. They looked at me, they're like, ‘All right, sister,’” said Alexander.

At one point, Alexander’s White editor had injected language into one of her articles and called the riots ‘a rampage,’ which made it to print. It signaled racial bias. She was mortified. “As institutions, they really have to do a better job of staffing up in non-riot times with people who understand this community and these issues,” says Alexander.

‘I now know that hope was naïve, given how little really changed after 1992.’

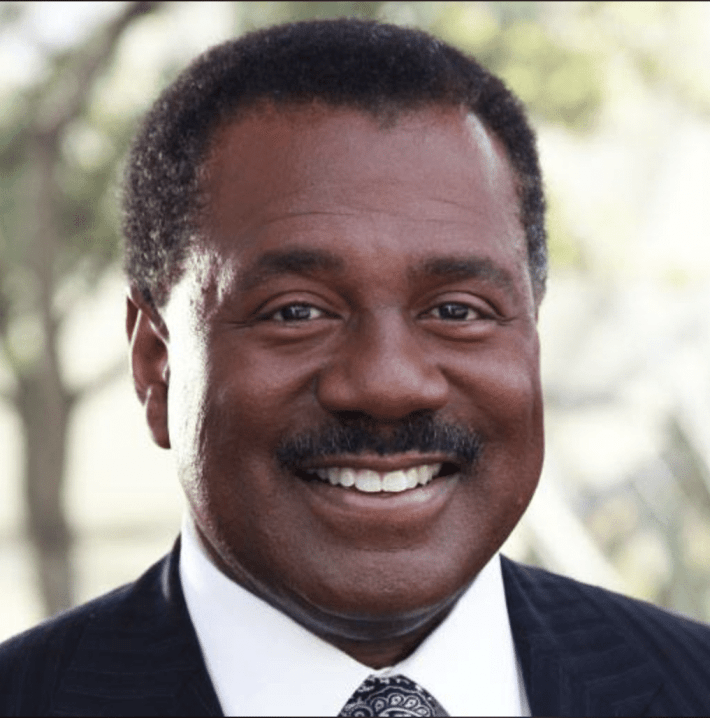

Meanwhile, veteran KABC/ Channel 7 anchor Marc Brown says newsrooms can do better this time around by looking beyond the week’s viral video. Visuals often depict Black bodies getting brutalized at the hands of police. Still, it’s crucial for reporters to dig deeper into the story and confront the systemic conditions that create such violent outcomes.

“We did that this time around, and found it to be a wellspring of reasoned, well-thought-out discussion of the problems that got us here. We must also listen to those who are expressing their grievances,” says Brown. “It is simply a much-needed evolution in the way journalists cover stories, which is always a good thing, as long as we adhere to the central tenets of good journalism.”

Brown was a young reporter during the riots, and just like Monroe, he was filled with anger, which gave way to despair, and hope. “I now know that hope was naïve, given how little really changed after 1992,” he said.

'We are not just Black reporters; we’re Black people'

Once again, many Black journalists are on the frontlines of these protests, and this time there’s a media reckoning. The idea of objectivity has mostly gone out the window. To separate oneself as a Black person from your work as a journalist is no longer a viable option.

“That’s what was missing. This inside perspective and context, because we were not able to sort of bring our own personal experience into it,” says Monroe.

Journalists are also getting assaulted and arrested by police while doing their jobs, and so they’ve become part of the story. In May, Omar Jimenez, a Black CNN reporter, made headlines around the world when he was arrested live on air in Minneapolis.

Monroe says there’s a chance for newsrooms to shift the way they’ve been telling these stories. “Some of us have seen the opportunity to sort of express what's been pent up inside us. We are not just Black reporters; we’re Black people. For people like me, who have been around for a long time and have covered these things, this one just feels different,” said Monroe.

There was hope that things would change in 1992, and it didn’t. The magnitude of the movement this time around and the fact that many non-Black people are engaging with anti-racism work is giving way to cautious optimism for more systemic change.

There hasn't been a day without protests or gatherings throughout this city for almost four months. The list of people dying at the hands of the police keeps increasing. In L.A, it’s the deaths of Andrés Guardado,18, and Terron Boone. The challenge is on for newsrooms all across the country to step it up, speak truth to power, and report injustices.

Brown is hopeful that this time around, there’s more nuance and critical analysis. “When violence broke out this time, responsible journalists were careful to speak the truth that violence is a small part of what was happening. And it was driven by genuine outrage, and by images contained in a video we all saw,” said Brown.

There was hope that things would change in 1992, and it didn’t. The magnitude of the movement this time around and the fact that many non-Black people are engaging with anti-racism work is giving way to cautious optimism for more systemic change. “Finally, people are going to listen, and there may be a chance,” Monroe said.

“So now, you have to drill down and fire up your machine in your newsroom to dig into that,” says Alexander.