[dropcap size=big]1.[/dropcap]The night is cold but the air is hot on South Main Street. Engines growl. Headlights feel like invitations. LAPD cruisers are flipping U-eys down every side street, prowling. I’m in pursuit of what I’m told could be a tlayuda currently surfacing in Los Angeles that is capable of teleporting me to Oaxaca in my mouth. This night in January is on.

I’ve been trying lately to rely less on my phone when navigating the city. I take a quick glance at a map to get a feel for where I’m going, and imagine the route in my head before driving. I’m looking for a part of South Main, right in South-Central, just east of the 110. South of MLK, but north of Vernon. More or less.

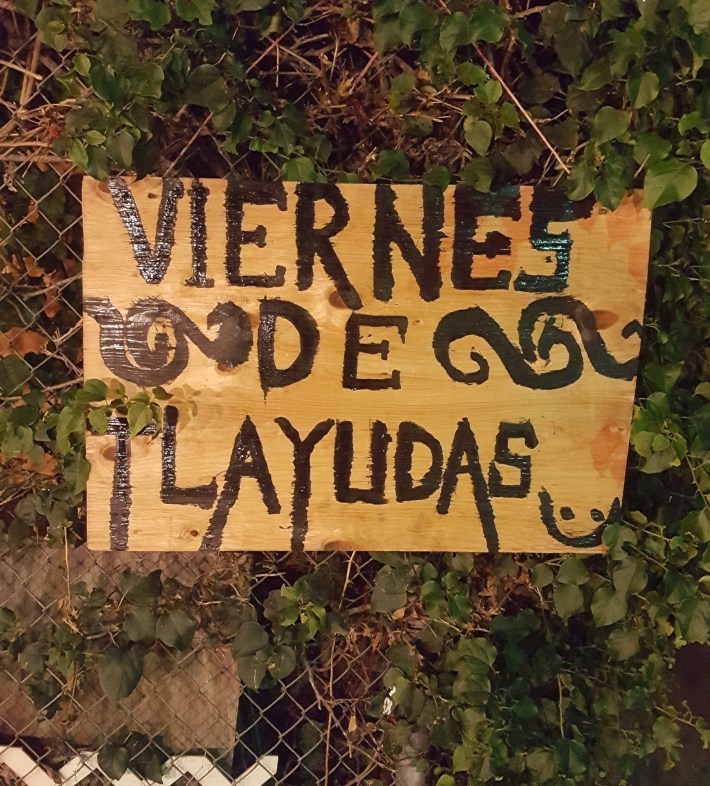

Once on Main, I spot my destination by observing a string of soft bulbs dangling over a verdant wall. That’s the universal symbol in the contemporary city for “Tacos Nearby.” I park and walk to the lights, to a driveway where a hand-painted sign announces: “Viernes de Tlayudas.”

Tlayuda Fridays.

I follow the driveway and squeeze past a white loading van and the walls of a historic home, to a wide rear patio. I can already smell the chunks of black mesquite coal, cackling in a barrel-drum grill alight in a far corner. There is a modest prep and serving table, where a woman stands. Behind her, manning the coals with pinzas and a legit attitude, is a rough-looking artist vato adorned with tattoos. In the middle is pleasant-faced Poncho, the man in charge of the tlayuda construction. I ask the lady for a tlayuda “with everything,” doesn’t matter what “everything” means. The grill man and the woman peer at me a bit suspiciously.

The tlayuda sound easy to make — the concept is basically an oversized tostada, with beans, cheese and cabbage, over a base of asiento grease to “seat” the beans. But this Oaxacan comfort dish is an enigma, difficult to duplicate authentically in any old setting. Something about the frisbee-size tlayuda itself is unmistakable. It is white corn and should be heated over coal. When a tlayuda reaches me, I know it should be crunchy but also a bit chewy; elastic enough to fold over without cracking at the seam, but firm enough to split in two with my hands when I want to share it with someone. It also has a subtle flavor, like, an ah-ha! that arises right at the border between the slight sensation of a tartness from the nixtamalization, and the sweetness of the corn itself.

A well-made Oaxacan tlayuda, on its own, is a masterpiece of maize. Generally in L.A., as at Poncho's, these are imported directly from suppliers in Oaxaca — uh, informally, yet in sophisticated familial networks via normal commercial travel.

Poncho barely looks up. I peer over. His hands have the plumped fingers of any Mesoamerican cook, man or woman, who touches a burning comal on a daily basis. He is splashing the tlayudas with asiento, the dark lard. Then the beans, slightly dark but not fully black beans, and slightly thin. Then the tlayuda takes strings of queso oaxaca (known also as quesillo), and finally, chopped cabbage (called col or repollo in Mexico).

Now Poncho turns to the grill man to add the plate’s main attraction, the meat. In Oaxaca it is usually tasajo, Oaxacan-style beef steak. Poncho’s has it, along with Oaxacan-style chorizo (strings of shimmery red meat balls laced together like pearls, crumblier than norteño chorizo). But the real treasure is Poncho’s calling card, a homemade pork blood sausage that is called moronga in the sierras of Oaxaca.

I sit down to take a bite. Tables before me are populated with South-Central Oaxacan locals, taking their last mouthfuls, or rubbing their bellies. One chomp past the threshold of no return, and I am transported. The smoke of Oaxaca. The burn of the sun in the valley. The feel of the dirt. The fragrant buganvilias, the wise old agave, the sweetness of the bread, the puddles in the grooves of the ground at the market, the firecrackers. Oaxaca came to me in Los Angeles.

The moronga sausage — served atop the tlayuda, not inside — made me weaken at the knees. Textured like grain, or like chunky sand, it is defined by an overwhelming taste that evokes textures like paté or truffly chocolate. I look up at the vendors and give them a pleading look.

Like, ‘Have mercy on me.’

Immediately I think that a perfect chaser for this teleportation in my mouth would be a small sip of mezcal. Fire in a glass, just like in Oaxaca. That’s when someone sitting nearby apparently reads my mind, opening an unmarked plastic bottle and offering me a mezcalito in a proper jícara gourd cup. I howl.

2.

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap] love how Los Angeles can just turn on you sometimes, in an instant. It’s like the matrix opens up, and you are past a boundary, into one of the unadulterated spaces belonging to any of the patchwork obsessions that mark our city. Usually those obsessions involve food, the ultimate dismantler of walls.

This is exactly what my first visit feels like to Poncho’s Tlayudas. On this first cold-but-hot Friday night, one of those Fridays that feels feverish with expectation, the pop-up envelops me. A DJ is set up to play music. It hovers happily around the bachata, cumbia, rock en español, reggaeton, and Spanish hip-hop hits of the last twenty years or so. A mural by the Oaxacan collective the Tlakolulokos, made out of re-purposed plastic dinnerware, decorates the wooden rear wall.

Poncho’s Tlayudas exists in the backyard of a house that serves as the offices for the Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales, or FIOB. This is a binational grassroots community group that is dedicated to promoting human-rights and food justice in both Mexico and the United States. Functionally, the organization helps keep Oaxacans in L.A. tied to their communities back in Oaxaca. Every day there is something going on; it is a glue for a variety of diasporas, a home-base for Oaxacalifornians of every stripe: Zapotec, Mixtec, Mixe, and so on.

And on Friday evenings only, from about 4:30 pm till the food runs out, usually by 10 or 11 at night, the team behind Poncho’s Tlayudas at the Frente offices’ backyard makes a valles centrales-style tlayuda that is a superior or peer to any other known tlayuda within L.A.

Which is funny when I recall this first night of going there. The modesty and casual air of the place is unsettling — Don’t they know what they have here?

I look back at the lady attending the puesto. She is Odilia Romero. Alfonso “Poncho” Martinez is her husband and partner. The grill man is artist Miguel Mendez, known as “Santo” or “Santito” to most around here. Odilia stands out. Her features in every respect are indigenous Zapotec, her nation, which is also her native language. Yet there is something so Cali’ about her. I can tell she knows I am going through a transformative experience eating her tlayuda, so after a while of staring at me, she deadpan announces in English — “I don’t even want to be here.”

It is a joke of course, sarcastic to the bone.

The source of the humor is that partly it must be true; Odilia later tells me she dislikes cooking, but can't deny she also has a talent for it. I laugh out loud.

Odilia, I quickly realize, is not merely a “wife” or “attendant.” Indeed as I get to know the pair, I realize they have an unlikely but dynamic partnership, one in which Poncho mostly cooks, because, as his partner says, he's better at it than she is. And outwardly Odilia — talkative and enormously self-assured — takes the reins of their tlayuda’s story.

3.

[dropcap size=big]O[/dropcap]dilia came to L.A. in 1981 with her family, from the Oaxacan town of San Bartolome Zoogocho. Poncho arrived in 1999, from the town of Santo Domingo Alborradas. This means she is from the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca and Poncho is from the state’s Central Valleys.

That distinction already makes them an odd couple to some Oaxacan eyes. The state in the lower groove of southern Mexico is home to 16 distinct indigenous groups. These and other minute geographical boundaries are present across Mexico, down to the pueblo level. They are extremely important for Oaxacans in L.A., reflected in distinct languages, customs, dress, and of course, in food.

Someone like me, a Mexican from the way north of Mexico, is practically an alien here. I tell them I traveled several times a year to Oaxaca during the time I lived in Mexico City. As we speak, Odilia and Poncho insist on understanding my identity primarily through the prism of my indigeneity. I give them my unconfirmed family accounts that we are part Baja California peninsular indigenous, actually, as well as Yaqui or Tarahumara from the central-north of the country. This satisfies them.

“I didn’t learn English until I was in my 20s,” Odilia tells me. “My first language was Zapotec, my second language was Spanish, my third language was English.”

Hearing this is startling. For generations the United States has regarded being bilingual as an affliction of Spanish learners to English. But in modern L.A., that bridge now includes English learners crossing over from any one of dozens of indigenous languages that Mexican immigrants might bring with them. This also means that younger Oaxacans in L.A. can be trilingual or partly trilingual.

During a visit to their South-Central home, Poncho and Odilia paint a picture of their history. It reminds me that a life in food sometimes finds you and not the other way around.

They were part of that early wave one or two generations back, when Oaxaqueños began settling into the fabric of our city in wide areas of Koreatown, Mar Vista, Palms, South Los Angeles, and Mid-City. Odilia and Poncho met fifteen years ago, at a Oaxacan community event. Poncho — a musician trained since boyhood at a Oaxaca state music boarding school called the CECAM — played in community-serving brass bands in L.A. He made money cooking on a line. Odilia was already active in the Frente Indígena. She was also building her profile as an interpreter for Zapotec speakers in L.A. County courts and hospitals, which she still does today.

They were friends first, Poncho and Odilia tell me, Zapotecs in the city. “We were like really good, good friends, and then I guess ... we had nothing else to do,” Odilia says laughing. “I mean, what am I going to tell you?”

They became a pair.

[dropcap size=big]F[/dropcap]ood binds everything that happens at the FIOB on South Main. Odilia and Poncho explain that with the constant activity, Oaxaqueños began bringing their best dishes to share at gatherings. Food sovereignty, after all, is a central pillar of the work. “You know how it is, everyone brings food, and wants to be the best,” Poncho tells me.

And with practice in the speedy kitchens of Los Angeles, Poncho, a musician at heart, realized he held that enviable knack that Oaxacans tend to have for magically making good food. One day Odilia’s parents decided they’d teach Poncho how to make moronga the way they made it back in Zoogocho.

“The recipe is from my great uncle,” Odilia says. In the pueblo, Odilia explains, her parents for some years would make the sausage at home on Wednesdays, and sell it at the town’s mercado on Thursdays. In Los Angeles, Poncho learned how to make a batch big enough to take to the streets. He went around K-town, offering it to Oaxaqueños who he had gotten to know playing clarinet in the bands.

“The first day, I sold 30 pounds in one hour,” he tells me.

Many people in the U.S. are familiar with chorizo, a reflection of the rich history of sausage making in Latin America. Spanish and Portuguese colonizers brought the Iberian embutido tradition to America five centuries ago. Today sausages shine in Colombia, Brazil, and Argentina, where the blood sausage is known as morcilla. It’s not exactly indigenous to the Americas, but after a few centuries, sausages are not some colonizing food piece for Oaxacans either.

“Cultural appropriation,” Odilia jokes.

The moronga recipe that Poncho makes to adorn his tlayudas essentially transmigrated with him.

[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap]t the Frente offices, with each passing festival, community event, or visit from a politician, the food became more exciting. One time, then-mayoral candidate Eric Garcetti arrived for a meet-and-greet. Poncho recalls fondly the images of the mayor chomping into a big tlayuda. Finally last summer, the pair set up a puesto out back at the FIOB house, and started selling tlayudas on Friday nights only. The moronga — the dark red swine blood embutido — would graduate from the delivery cooler for knowing Oaxacan connoisseurs, to the unsuspecting taste-buds of strangers drawn to the sign of Viernes de Tlayuda.

Word began spreading farther.

“Everyone from the Sierra Norte, the Isthmus people in Santa Ana, the Central Valleys people, who live mostly in Santa Monica,” Poncho explains. “The people who come to eat here are also from Puebla, Guerrero, and Guatemala.”

“I know my customers,” he adds with a winning smile.

4.

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]t’s March. I stop at Poncho’s and the rush has passed. Santito has his prongs on the mesquite in the barrel, but the fire is calming. Santo looks like he could have walked off a Tlacolulokos mural himself, like the kind currently up at the Central Library. He is an artist, a danzante, and he tells me he’s lived all over the United States. Families sit tightly together in the chill. The flow is relaxed but concentrated.

I didn’t plan on being here and hadn’t alerted Poncho or Odilia I’d be coming. Sometimes, spontaneously, a tlayuda just feels right. It has been a long day, and a long week, driving around L.A., all of us hustling.

Nearby sits Gabriel, one of those regular L.A. dudes — and by that I mean a golden brown-colored man with not a lot of facial hair and not a lot of height on him. A typical working Angeleno. Gabriel made it. He tells me he crossed the border years ago, through the desert. He started working at a perfume store in L.A., then learning about perfumes, then figuring out how to sell them better.

“I tell my friends,” Gabriel says to me, sounding like a sagely dollar-sign self-help guru. “You have to make your work work for you.”

We eat together. Gabriel is enjoying his life, hustling under the radar in the tenuous sense of sanctuary offered by the big city. He’s not Oaxacan, he tells me. He’s from Guerrero. There was an old lady from Puebla back in the highlands, he says, who made Oaxacan tlayudas in his town. He drives here for these — Gabriel is an immigrant foodie.

Switching to English, he says: “I know what good food tastes like. And this is good food.”

5.

[dropcap size=big]M[/dropcap]ost Oaxacalifornians I’ve ever met, young or old, man or woman, have a playful sense of humor, fans of banter with strangers, nonchalant poetry. Poncho, perpetually sunny, speaks Spanish with a slightly more “indigenous”-sounding accent, rounder on the words. His English remains minimal. Odilia speaks English with a totally rad SoCal accent. She’s very upfront with her humor, and a bit bawdy about it, needling people or assumed truths that maybe these days she shouldn’t be needling. Odilia is free.

But simmering below her biting humor is a fierce political commitment to elevate the urban-indigenous people of Los Angeles. There are an estimated 200,000 Oaxaqueños in L.A., but no one knows for sure because a proper tally doesn’t exist. We tend to regard our Oaxacan neighbors as the pleasant young guys in the kitchen or on the bus, but little more. The U.S. only classifies an immigrant’s nationality. Over many conversations, Odilia describes appalling incidents of discrimination against indigenous Oaxacans that she’s witnessed as an interpreter. In the courts, at the Los Angeles Police Department, and even among the interpreter community at large, prejudices flourish, she says.

“They have already an idea of what an indigenous person is, and I’ve seen them,” she tells me. “They are earlier immigrants, Mexican Americans, migrants from Argentina, Colombia, elite Mexicans, and they don’t make an effort. I tell them, our profession is in the major league, and you treat it like it’s little league.”

Today, Oaxacans are closer to the average Angeleno than most of us tend to acknowledge. Not only are plenty of Oaxaqueños cooking your meals at an unimaginable number of Korean, Thai, French, American restaurants, diners, trucks, etc., but plenty more such as institutions like Guelaguetza by the Lopez Family, and fusion newcomers X’Tiosu in Boyle Heights, have convinced me that more than ever, Oaxacans are among the leaders of the Los Angeles food universe.

Another night, Odilia has just returned from a difficult and exhausting trip to Oaxaca. She has been named, in an upset vote, leader of the Frente Indígena de Organizaciones Binacionales — its first woman elected president in its nearly thirty-year history. She said the opposition from “some of the boys” was strong, but in the end, Odilia remained cool and victorious. Gender hierarchies among the urban-indigenous are slow to shed.

“I think in many ways they expect us to be at home, cooking, and we’re not like that,” Odilia says of herself and other Oaxaqueñas, women who are on the ground and in the community working. “People ask him, ‘How do you stand living with her?’”

“... And people think we’re weird,” she goes on. “Well, we are weird.”

6.

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]t’s late April now. Spring so far in Los Angeles has been a succession of bright and sunny days accompanied by nights scattered with that wet and chilly on-shore flow. I couldn’t find parking. The quality of the streets is poor in South-Central.

I have another tlayuda. Slayed. Places like this must be preserved, I think to myself, somehow. Right now, as Los Angeles grapples with how to legalize street vending, I am reminded that all over the world, since the dawn of time, this sort of enterprise has organically popped up when people mix together in a new place. Yet even with a mayor visiting Poncho's once, we're unable to fully protect and encourage food vendors like them in the Los Angeles bureaucracy.

Rosalinda Meza, a 34-year-old Oaxacalifornian from Koreatown, is helping Odilia tonight. She got her degree at UC Davis — incidentally, I realize that a lot of the second-generation Oaxacalifornians have their UC and Cal State degrees in pocket.

“I’m Oaxacan. But I’m also Central American,” she says. “And I’m Korean. I’m from Koreatown, but it’s really what I call Central Americaville, like Beverly-Normandie-Third, every kind of Central American, and every kind of African immigrant.”

She is Zapotec. One side of her family is from Zoogocho, too. We talk about the integration of Oaxaqueños in Los Angeles, and the diverse distinctions within the community. Like others, she travels back and forth to her family’s hometown in Oaxaca all the time. She understands what I mean when I say this tlayuda reminds me of my many visits to Oaxaca.

“Yeah, it’s crazy, because even in Oaxaca, it’s hard to find a decent tlayuda,” Meza says. “That’s why when I go [to Oaxaca City], I just end up getting a hamburger.” We laugh. “You know, at the puesto on the street — ugh! They're so good! With the habanero and the pineapple.”

It is ironic. We can't stop laughing at this.

“I mean, my grandma makes the most complex dishes, but sometimes I just want a hamburger ...”

Not in Los Angeles, though. Not tonight. As long as we have Poncho's Tlayudas, a sensory trip to Oaxaca on a Friday night is just a bite or two away.