I had just crossed into Eaton Canyon when I heard the news on the radio: another body had been discovered by cleanup crews, bringing the death toll from the Altadena fire to 19 people, bringing the overall death toll from January’s horrendous wildfires to 31.

It’s a gut punch. Not just because of the sheer tragedy of it, but because even now—almost seven months later—L.A. County hasn’t recovered from this fire, even as we deal with the slow-burning consequences of a broken immigration system, the glowing embers of a housing crisis, and the endless blaze of gentrification fueled by corporate raiders that seem to profit off disasters.

So I did what I often do when I need to feel something other than numb: I went to see a close friend. In this case, my sincere friend Rafael Agustin. Rafa is a noted author, TV writer, and filmmaker, but he’s also a dude I trust to tell me the truth about his city.

It was a cool, cloudy Tuesday in July—the kind of day that could’ve been ordinary if not for the fact that it was Rafa’s first day back in his home since the fire. His two-story home — that he shares with his mom and grandmother — was spared from the flames, but not from the trauma.

“I got the keys back from the hygienist just now,” he told me, standing in the middle of his kitchen. “They said, ‘Rafa, congrats. Your home is officially safe for you to return.’”

Rafa is talking about his industrial hygienist, a specialist trained to clean homes of invisible but dangerous contaminants like lead, mold, smoke damage, and toxic air particles. I remember seeing photos of his place after the fire, and standing in it now, it’s hard to believe it’s the same house.

The hygienist did a great job. There’s almost no sign of the smoke damage or toxic chemical residue that had made the house unlivable for months.

The pool still looks like a toxic swamp, its surface a murky green mirror of everything left undone. A black cable dangles from a nearby street post like some forgotten vine. Neither the county nor the utility companies claim responsibility.

“I think maybe it was from a company that doesn’t exist anymore?” Rafa says, half-joking, as we peer over the wall.

“There were days I couldn’t get out of bed,” he says. “And then I’m like, ‘Snap out of it. Let's go!’

Most of his neighbors haven’t even started the months-long gauntlet: debris removal, lead abatement, rebuilding—if they can. And in the worst cases, they’re still waiting for the most devastating kind of closure: the discovery of a loved one’s body buried in the rubble.

We take a slow car ride through the neighborhood, and for the first time since February—the last time I’d been here—I see the devastation with my own eyes. I hide my heartbreak as best I can as I witness the damage. All around Altadena, what were once warm, lived-in family homes are now fenced-off empty lots. In some cases, the only thing left standing are the gates, guarding nothing but memory.

We look out toward the San Gabriel Mountains. The view is beautiful, haunting.

“It was never this brown,” Rafa says. “It’s like a constant reminder of what happened here.”

Down the street, many businesses are still boarded up or reduced to ash. Some of the buildings look like the fire ended yesterday.

“We were lucky. But you walk down Lake, and it's like time stopped. The Army Corps came quickly to the homes. Not the businesses. And definitely not the uninsured.”

We take a drive down Lake Avenue, one of the many devastated areas of Altadena, while Rafa talks about lead abatement and volatile organic compound testing.

“It's like a crash course in emergency response and recovery,” he says. “I didn’t even know what VOCs were. Or what an industrial hygienist does. Now I’ve had three.”

“Before the fire, five percent of homes sold were bought by investment firms. Now it’s over fifty. They’re gonna turn this place into condos,” Rafa tells me, his voice tight with both anger and exhaustion.

He tells me about the endless back-and-forth with insurance, the bureaucratic confusion about who was in charge of what county? City? State? And how no one seemed to know who was responsible for making sure his 100-year-old grandmother could breathe safely.

So Rafa did what most Angelenos do when the system fails: He figured it out himself. He called his state senator. He helped raise funds. He advocated for neighbors. He put his body on the line. And still, the work continues.

“There were days I couldn’t get out of bed,” he says. “And then I’m like, ‘Snap out of it. Let's go!’ Then I started making calls to raise money to help, anything to bring resources to the area.”

The biggest shift came the day he noticed something was missing: The smell of smoke. It had haunted the house for five straight months. The first person to catch the change wasn’t him—it was his mother.

“She walked in and said, ‘Oh, now it finally smells like Altadena again.’”

Not everything smells like home, though. A lot of neighbors are gone for good. Some lost their homes. Others lost hope. Some sold to corporate developers who are already swooping in like vultures.

“Before the fire, five percent of homes sold were bought by investment firms. Now it’s over fifty. They’re gonna turn this place into condos,” Rafa tells me, his voice tight with both anger and exhaustion.

In moments like these, you realize that the fire isn’t just a natural disaster. It’s a portal. It opens the gates to all the other problems we already had: housing inequity, displacement, gentrification, and environmental racism.

But it also revealed something else: resilience.

Last week, Rafa stood outside his house as a power-wash crew prepared the exterior. A Mexican-American family passed by, just returning after six months of displacement. They stopped and chatted. Then an elderly couple—new homeowners who had closed escrow the day of the fire—walked up. Then, visiting parents from a rental across the street.

All of them, converging on the sidewalk like it was a block party from before the world fell apart.

“It was beautiful,” Rafa said. “We were all just craving community. Normalcy. We want to rebuild.”

That doesn’t mean forgetting.

There’s an older man they used to call “The Mayor” who stayed behind during the evacuation. He hid in his basement and watched over everyone’s homes that were still standing, doing what he could to fend off looters. He also did little things, like taking out their trash or letting people know when county officials were snooping around. But after a while of staying in his basement, waiting for the Altadena he grew up in to come back, the man they called “the mayor” sold his house for close to a million dollars.

“He said this place isn’t his Altadena anymore,” Rafa explains. “Especially since his church burned down and a lot of his friends and family are gone.

And maybe that’s the tragedy beneath the tragedy.

The homes can be rebuilt. The air can be cleaned. The walls can be scrubbed down by certified professionals in hazmat suits.

But who gets to come back? Who gets to call it home again?

“I told my mom,” Rafa says, “We’re not going back to Altadena. Not psychologically. Now we live north of Pasadena.”

He’s not wrong. But there are flickers. Signs that the spirit isn’t entirely gone. Places like a random taco stand posted near the rubble of a pizza joint or a 40-year-old burger joint that somehow survived the blaze that razed every other business around it.

In the months since the January fire, Altadena residents have taken recovery into their own hands. Community-led groups like the “La Viña Rebuilders”—24 fire-survivor homeowners who all hired the same contractor—are pooling resources to expedite reconstruction by coordinating permitting, shared building teams, and cost-reducing floor plans. A grant from the Pasadena Community Foundation and San Gabriel Valley Habitat for Humanity will fund rebuilding for 22 low-income and uninsured homeowners over three years, many of them seniors or multigenerational families determined to remain in their neighborhoods. Meanwhile, the Army Corps of Engineers and county agencies are recycling metal, concrete, and even trees from the rubble, a process that reduces waste and turns debris into building materials for new homes.

And Altadena residents are finding creative ways to fight for their community. According to Local News Pasadena, local homeowners are embracing Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) as both short‑term housing and long‑term value, allowing families to stay on their land while reconstruction moves forward. ADUs are particularly helpful in fire zones: they can serve as modular, on‑site temporary housing and later be converted into rental units—often qualifying for streamlined L.A. County permitting under emergency measures.

On the grassroots front, groups like Altadena Not for Sale, the Altadena Collective, and Altadena Builds Back Foundation are organizing to resist corporate land grabs and preserve local ownership. They’ve introduced yard signs, launched car caravans, and pushed elected officials to support community land trusts and moratoriums on speculator purchases of fire‑damaged lots, according to a report by the L.A. Times.

Meanwhile, SGV Habitat for Humanity, funded by a $4.55 million grant from the Pasadena Community Foundation’s Altadena Builds Back Foundation, will rebuild 22 homes over three years for low-income, multigenerational families. Their plans include pre-approved designs for primary homes plus ADUs to accelerate permits and reduce costs.

Together, these approaches are a pastiche of resistance to the corporate takeover of Altadena.

But still, the facts on the ground are hard to ignore. I tell Rafa that seeing all this destruction makes me kind of sad but he says it actually a time of hope for him.

“I’m going to spend my first night in my bed tonight,” he says with a smile.

Rafa also puts something in perspective. The recent proliferation of empty lots around town are actually a sign of progress.

“Before it looked like a massive grave yard or something, like there had been a war and everything was blown to pieces,” he explains. “Now, it’s like a place full of possibilities. I imagine it was a little like that when they first started to build community here in Altadena.

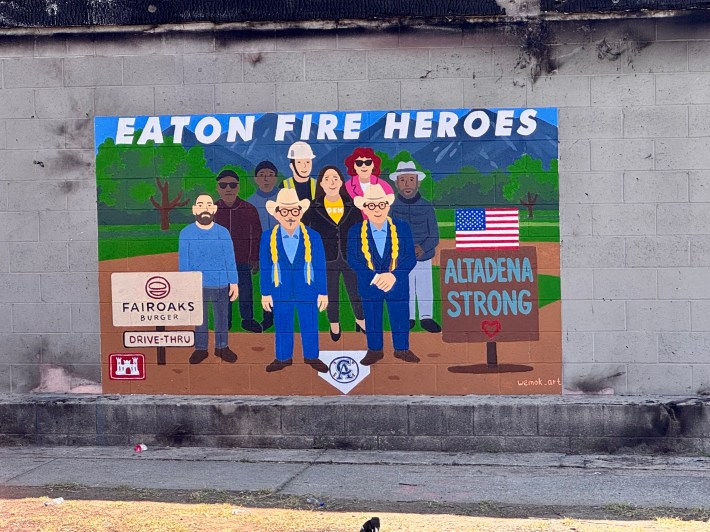

He takes me to a home that has a beautiful mural covering an entire wall—flowers, bees, birds, hearts, colors of all kinds, and the words “Altadena Strong” on it.

“Altadena is one of the last places left for working-class families,” Rafa says. “We have to fight for it to come back.”

This is what it’s like to move back to Altadena right now—yes it’s empty lots and the remnants of devastation all around but it’s also people like Rafa, his neighbors, and their advocates coming together to create resilience, equity, and local control in the face of displacement and disaster capitalism.