On January 17, 1994, a magnitude 6.7 earthquake struck Northridge, the San Fernando Valley, and greater Los Angeles County areas, creating damage that took many in these communities several years to repair.

According to a report published by the Southern California Earthquake Data Center, the earthquake's epicenter was located in Reseda, just one mile south of Northridge. Neighborhood landmarks like the Northridge Mall and the California State University Northridge (CSUN) campus were severely damaged.

Buildings across the Valley were red-tagged, indicating that destruction had been so severe that people were restricted from entering the premises without proper supervision.

“In the immediate years following the quake, everyone talked about what they would do if another one hit," says Carmen Ramos Chandler, a long-time resident of the San Fernando Valley. "What reinforcements had been done to vulnerable buildings and other contingency plans? Now, the earthquake is a distant history and I think many people have forgotten the lessons learned."

Chandler is one of the many survivors who are sharing their stories of the Northridge Earthquake with L.A. TACO. January 2024 marks 30 years since the earthquake, and each survivor has a range of stories to recall about everything that happened and what they experienced.

Carmen Ramos Chandler ~ Northridge and Studio City

Carmen Ramos Chandler, a reporter for the Los Angeles Daily News at the time of the earthquake, and currently director of media relations at CSUN, shared what it was like to be a part of the campus community after the earthquake, which she experienced with her partner at their newly purchased home in Studio City.

"I’m hearing this roar, I mean a roar. I swear to God, it sounded like a freight train was going full speed straight to my bedroom," says Ramos Chandler about that morning. "You’re used to the rolling earthquakes when they hit. This was violent, shaking, throwing, literally, throwing me up off the bed… like you know, The Exorcist or something, and the bed rolled because we had hardwood floors… and there’s no bed underneath me."

Later she was assigned to patrol Ventura Boulevard in Sherman Oaks, so she began reporting, assessing the damage, observing, and talking with residents.

H. Hoffman ~ Porter Ranch and Simi Valley

Hoffman, a long-time resident of the San Fernando Valley, speaks about the impacts of the earthquake that lasted well beyond the physical shock.

"I got to finally, really understand what post traumatic stress was. It was just, it was the feeling of being so overwhelmed but the adrenaline inside of me just said ‘you've gotta go’,‘you gotta do it’, ‘you gotta do it’, ‘you gotta make it happen.’ I never felt that I couldn't do it. I had to keep going. But there were days when I would stand there and say, ‘I can't even move my feet.’"

"The community itself was, of course, just wrought with destruction. You know, we didn't live that far from CSUN, and the parking structure that came down every time I would drive by it—and people—it became this this iconic tourist attraction. We had a lot of what I like to call 'lookie-loos,’ it's not a nice phrase. A lot of people coming from outside of our community just to just stand there and just.... look. I know that they were doing it, not as necessarily an evil type of thing for us, but the community itself became very protective of what we were going through and we really didn't appreciate all of the outside influx it created."

"It created traffic in an area where we were having trouble just navigating around roads, cause some of them were still impassable. It just created a sense of, you know, we're not a freak show. I think that it's very important for people to not so much to remember the Northridge Earthquake, but to resurrect what went on and and how people were affected and what the recovery was like... because once again, you know... it's- so many years ago and nobody really thinks about it. There are so many learnings that came out of that earthquake, you know, you know, God forbid we go through another experience like that we may... not lose people."

Nicole Peterson ~ Woodland Hills and Tarzana

During the earthquake, Nicole Peterson was a high school senior. Today she reflects on how much time has passed and changes in how the community chooses to memorialize the event.

"The three people in my family who experienced it were my mother, myself and my father. It was totally unexpected and probably up to this point, one of the scariest things of my life. After that point, for years I kept shoes and a flashlight, always by my bed. It was the type of earthquake where... instead of things swaying side to side, it went up and down. I remember trying to run to the door. I was in... a bedroom that was right by the kitchen and so to get outside, I had to walk through the kitchen.. .and there were dishes, you know, flying and... our front door opened... and our golden Retriever ran out front. So while the earthquake was going on, I was barefoot and running after the dog, you know, it's still so vivid."

"Anniversaries seemed significant, like even like when that day came around, people would still talk about it, like 'where were you when it happened?' kind of thing and they would swap stories even if it wasn't, you know... anything dramatic. It's kind of interesting just to.... share and reflect on that, and I remember it. I can't believe now that we're almost at the 30th anniversary."

Raymond Garcia ~ Glendale, Sylmar, Woodland Hills, Northridge, and Oceanside

Raymond Garcia shares his memories as a small, private school teacher in Reseda and already a survivor of the Sylmar earthquake in 1971.

"I had been in the earthquake before in 1971. So... I was as prepared as you could be for something like that… had a flashlight, had hard shoes, had nothing hanging over my bed, had a clear path to get to—to the outside if I needed to…. In contrast, I got out of my room within seconds, my roommate was buried in stuff, and it took him a good half an hour to dig his way out through all that…. He was originally from Detroit, so this terrified him. He was absolutely over the top, terrified, scared. I don’t —although he didn’t say it. I know later on because he got a flashlight for every single room after that. Every single room."

Craig Baker ~ Van Nuys and Sylmar

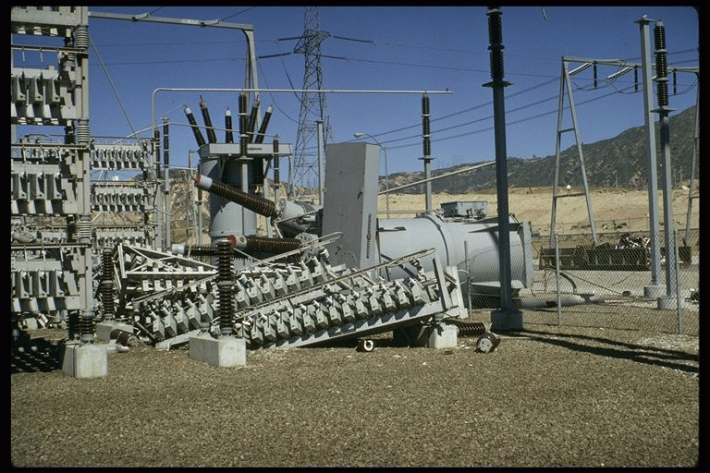

Craig Baker tells stories about his time as a construction electrician with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

"Much of the power distribution equipment was severely damaged in the North Valley, and I was one of a few dozen workers sent to the Rinaldi Receiving Station… we had four crews working 24 hours a day seven days a week… trying to get the power back on in the community as soon as possible. Workers had pride in their ability to do what was needed to help. We worked hard, with few breaks. We would only stop working for a few seconds when an aftershock happened, holding our hands up in the air to avoid crushing our fingers. The violent shaking never bothered anyone. Nothing did. Everything inside my home hit the floor and broke, but that doesn’t matter because working extra hours more than made up for it financially. I was doing nothing but work and sleep that year. I did not see any news reports or friends in 1994.

Nate Thomas ~ Koreatown and Northridge

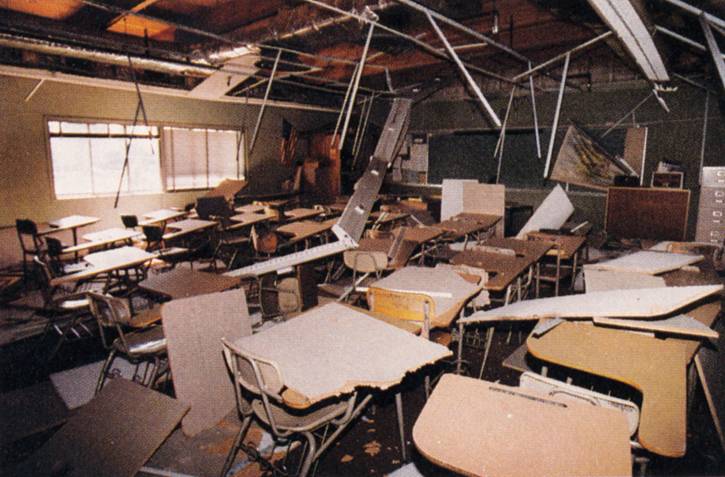

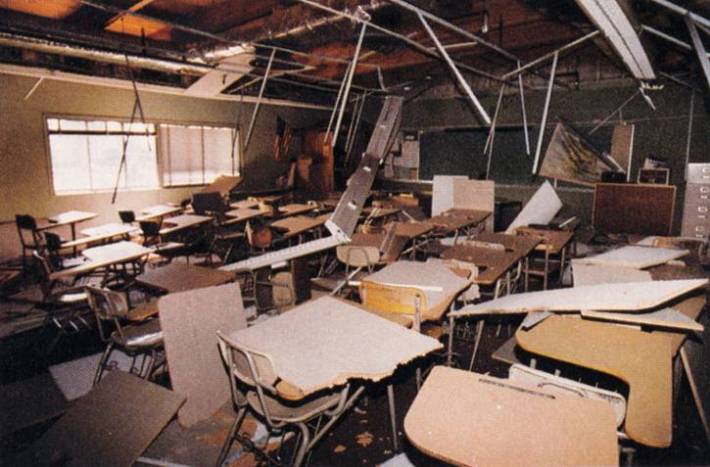

Nate Thomas, a CSUN lecturer at the time, who is now head of the film production option, shares memories of the aftermath of the earthquake on campus. He says the most vivid memory is seeing the damage at CSUN.

Thomas writes, “As a faculty member, about three weeks after the earthquake,, emergency personnel accompanied me as I needed to retrieve valuable teaching and personal materials. The building, now called Cypress Hall, was damaged but not destroyed. With required hardhats and escorts, I was allowed in. The interior of the building and my office looked like a building in a war zone with destroyed walls, debris, desks, and bookshelves overturned and windows all broken out. These scenarios were all around you. Once the campus opened, having to teach classes in mobile trailers (which were retrofitted as classrooms with blackboards, seating, video projectors, and the technology of the time) was challenging.”