[dropcap size=big]F[/dropcap]ist up in the air, hoop earrings on point, with an assured smile and steely eyes, Los Angeles high schooler Edna Chavez was one of the most talked-about youth speakers at the March for Our Lives rally in Washington D.C. earlier this spring. She told an audience of half a million about her family’s connection with gun violence: the death of an older brother in a neighborhood where Chavez “learned to duck from bullets before I learned how to read.”

Her speech resonated for its power, but also because it was, whether attendees knew it or not, a direct connection to Chavez’s social-activist ancestors. Fifty years ago, tens of thousands of Southern California Mexican-American students walked out of their high schools in what became known as the East L.A. Blowouts. They marched to protest schools that had failed to protect them — not against gun violence then, but against institutional racism.

The Blowouts anniversary didn’t get much coverage outside of Southern California, and a couple of local conferences in the early part of the month. But on the first floor of Cal State Los Angeles’ John F. Kennedy Library, next to the info desk and just behind tables where students study, stands “Eastside Blowouts: Through the Eyes of Chicano Media.”

RELATED: KCET Documentary Explores Birth of La Raza Newspaper

Organized from the personal collection of Cal State Northridge Chicano Studies emeritus professor Raul O. Ruiz, the small exhibit tries to connect the event to the youth of today through the unlikeliest of mediums: newspapers.

An introductory label explains that not only did the mainstream media ignore Mexican-American issues at the time of the Blowouts, but so did the Spanish-language daily La Opinión and even longstanding community weeklies, which the label’s unsigned author bitterly notes instead published “endless articles of local Barrio Queen contests” and mostly served as “merchant advertisement rags.”

That ignorance allowed a newspaper scene to flourish around East Los Angeles — the “social media of its day,” the label points out in an obvious-but-necessary comparison. They “focused and analyzed the important issues: Vietnam, education, police abuse, poverty, unemployment.”

Swap Vietnam for immigration, and all these issues continue to resonate with Latinos today. More importantly, they only get big coverage not in the MSM but, yep, social media.

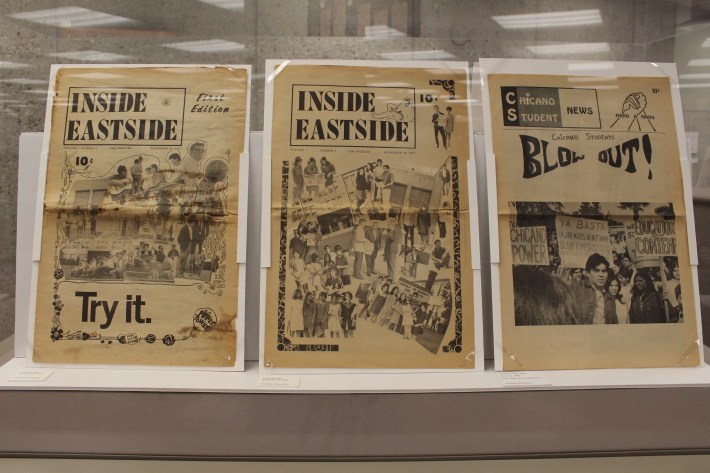

The exhibit knows that its primary audience is Cal State LA students, who are Internet natives. So it’s heavy on showing actual newspapers. Presented are copies of long-gone periódicos like Inside Eastside, La Raza (whose photo archives got their own exhibit at the Autry Center as part of “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA”), Chicano Student Movement, and more.

“Chicano papers make no pretense toward being objective.”

[dropcap size=big]P[/dropcap]eople who remember print newspapers will be shocked at how physically large even small publications were back in the 1960s, compared to the anorexic paper efforts of today.

The papers of then read like the memes, videos, GIFs, tweets, Snaps, and Facebook missives youth offer today. Many are photo-heavy, with pictures of young men and mujeres who look as fierce and stylish as Chavez. The pages feature poetry alongside media critiques against the Los Angeles Times; funny illustrations break up investigative stories or first-person accounts heavy on the youth lingo and outrage.

RELATED: The Brown Buffalo & St. Basil's ~ Wilshire District

“Who are the Brown Berets?” reads one column about the Chicano paramilitary organization. “You know, ese, when you lay it on the line, there are people who mouth about taking care of business, and there are people who TAKE CARE OF BUSINESS [caps in original].”

Ruiz could’ve easily made “Eastside Blowouts” a solipsistic ode. His bylines continually pop up in the clippings offered; he took most of the blown-up photos offered to let visitors take a break from type. Some of the most iconic photos of the Chicano movement—Brown Beret men sitting on a curbside, women members arranged in formation—came from his camera and are thus part of the exhibit.

In one particularly meta moment, Ruiz includes a 1977 book whose pages are turned to a history of the Chicano press that he wrote. The passage includes a phrase — “Chicano papers make no pretense toward being objective” — that popped up in the introductory label.

But Ruiz walks himself back. He smartly offers primary documents of important events at the time that he juxtaposes with how the Chicano press covered them—a sort of Journalism 101. One great example: the original press release issued by the Brown Berets after their headquarters were firebombed; the photo that accompanied it showed up in the front page of a newspaper right next to it.

“Eastside Blowouts” is a quick but effective history lesson that knows its limits. All it seeks to do is spark some interest in its visitors, and hope it carries into the future to eventually germinate in future minds, just like the East LA Blowouts lived in Chavez’s speech 50 years later.

When I visited, three Latina students stood in front of a newspaper for about a minute. “Garfield?” she muttered out loud, referring to one of the high schools that walked out. “That’s crazy.” Then they walked on, talking about how cool that their high school took part in the Blowouts.

“Eastside Blowouts: Through the Eyes of Chicano Media” continues at Cal State LA’s JFK Memorial Library (5151 State University Dr., Los Angeles) through May 31.