[dropcap size=big]H[/dropcap]e was a high school football player and class president in the Central Valley. Then he went to Panama with the US Air Force, where he became a Baptist preacher. Back in California, he went to law school at night and passed the bar exam. And after that, he was introduced to a nascent movement embracing the new cultural and political categorization of “Chicano.”

In L.A. in the late 1960s, Oscar Zeta Acosta became the movement’s lawyer. But the enigmatic Brown Buffalo was in a way just getting started.

In 1970, Acosta ran for sheriff of Los Angeles County. His platform included a commitment to the “ultimate dissolution” of the department itself. He earned more than 100,000 votes, but still about a million short needed to beat the eventual winner, the long-serving Peter Pitchess (who had started his career as an FBI agent).

Four years later, in 1974, Oscar Zeta Acosta disappeared in Sinaloa, Mexico ... leaving no trace, to this day.

Acosta, the subject of a film that premieres Friday on PBS stations nationwide, is easily one of the most deserving of renewed attention among figures from the American counterculture, and in state and Mexican American history. The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo, directed by Phillip Rodriguez, is a genre-defying docudrama that offers exhilarating new details on the life of the self-proclaimed Brown Buffalo.

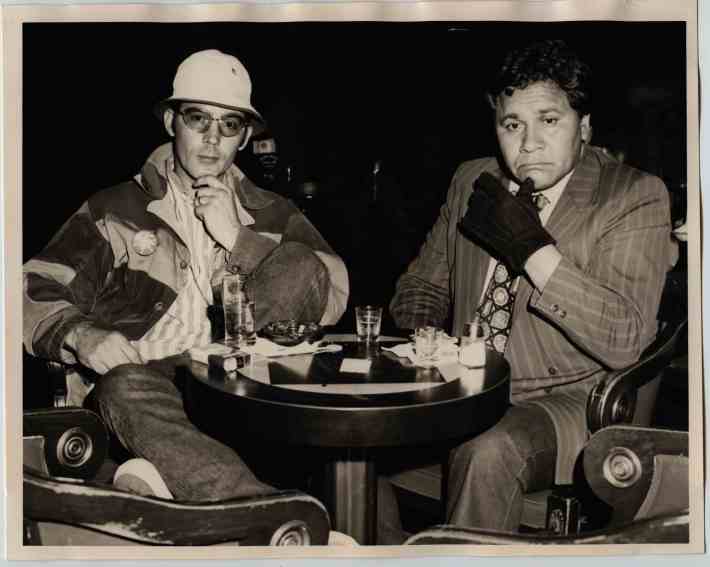

In the 44 years since his presumed death, Acosta has endured as a renegade in the footnotes. As the basis for the sidekick character in Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, he is identified fondly for millions as Dr. Gonzo, a frequent subject of the author’s gonzo journalism. But for readers who know their brown history, the patchwork of Oscar Zeta Acosta’s life make him a nearly mythical type, an alpha-male who would have definitely faced accountability over some of his social behavior if he were still alive today.

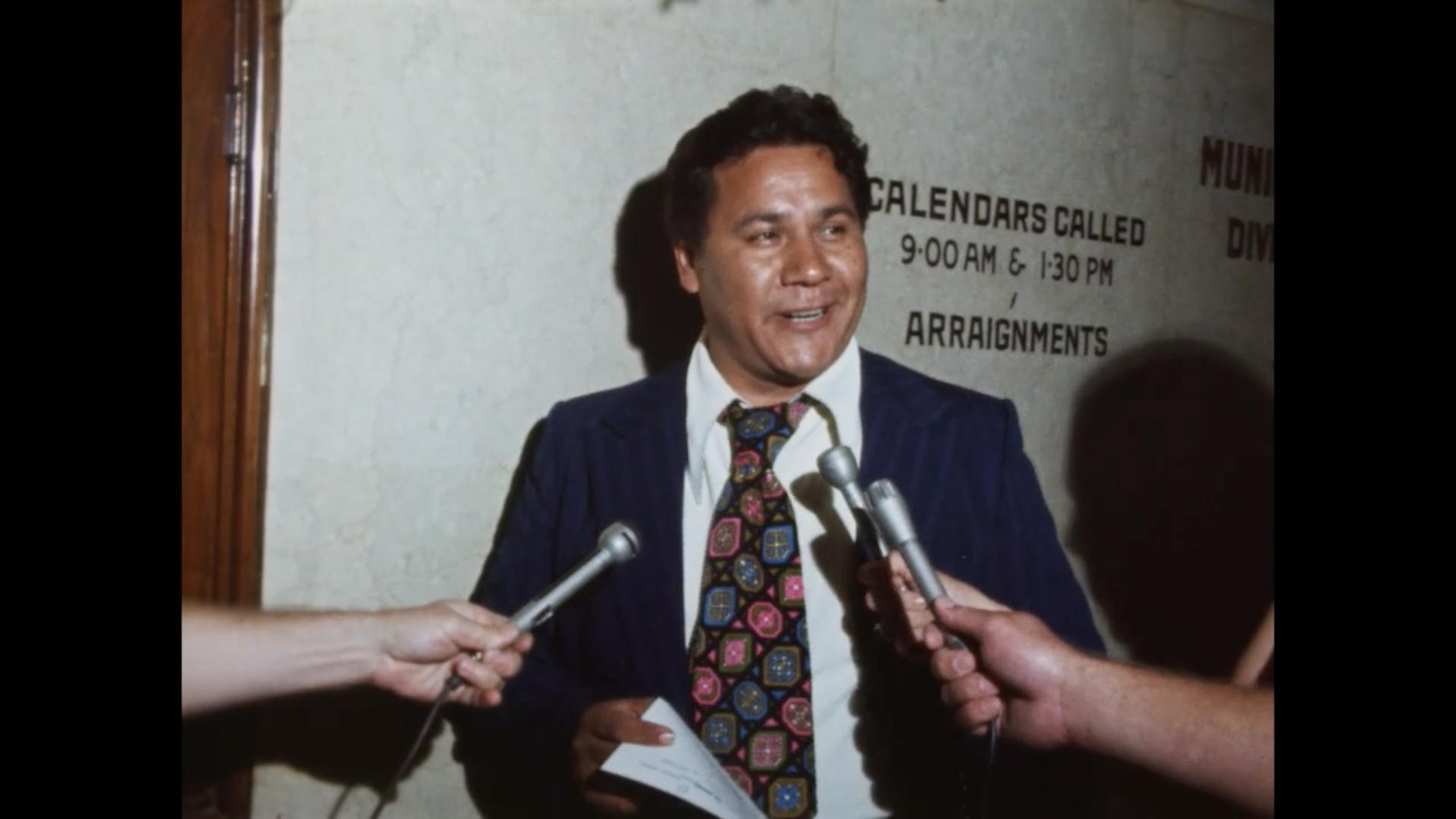

The new information in the film is astounding. Viewers learn that Acosta got his two-book publishing deal — the results seen in The Revolt of the Cockroach People and The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo — after threatening to sue Thompson and Rolling Stone magazine. The film features never-before-seen footage of Acosta at rallies and before the press during his defense of the East LA 13, and during his run for sheriff.

“We are the janitors of the world!” Acosta screams in one.

“It is the police department and the sheriff’s department that produce a lot of this crime that we hear of,” he declares in another. “They are not a policing agency any longer, they are a militia. They are not to protect people from injury, but basically to keep people in line.”

The clips are jewels. But the makers of the The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo didn’t have enough from the available archives to fully “accommodate” Acosta’s story, Rodriguez explained in an interview.

“He was like a ghost,” producer Alison Sotomayor told LA Taco.

So the filmmakers decided to make the project a semi-scripted story, where Acosta and his contemporaries are played by actors in period dress and hair, talking to someone just beyond the camera as in documentary “interviews.”

Celebrity Political Cameos

Viewers will find either freedom in the narrative experiment, or feel a tinge of impulse to dismiss the whole set-up as hokey. I suggest holding on.

After a few minutes, the mind and eyes adjust to the costumes. The acted portrayals of Acosta, his women and wives, his friends and cohorts in law and activism, provide key dramatic context and are played in performances that are uniformly entertaining and wise.

We watch Acosta (played by Jesse Celedon) make a head-on attack against the LA court grand jury selection system, asking frowning potential judges if they knew “any Mexican Americans.” We watch Acosta open up his briefcase in a courtroom with his stash of drugs emanting scents inside.

‘They are not a policing agency any longer, they are a militia.’

In another moment — as written by Hunter S. Thompson in a Rolling Stone article — the pair get drunk and wasted and Hunter watches as Oscar sets a fire on the lawn of a fancy judge, played in this case by the real-life current California Attorney General, Xavier Becerra.

“I know he’s seen me, but he’ll never admit it,” Acosta tells Thompson back in their car, then the two begin cackling like wild devils, driving off as Becerra’s character looks from a window in his PJs.

Former LA mayor and current candidate for governor Antonio Villaraigosa also makes a scripted cameo in this film, as a judge warning Acosta about his Chicano-esque business cards in a courthouse hallway.

“The thing I liked about Oscar was,” the Hunter character tells the camera. “He was always willing further than I was.”

Yet for all the incredible experiences that colored his life, Acosta is still largely associated with the phrase “fear and loathing.” Acosta was furious with how he was depicted in the book: he was erased as a real person but still there, described as a “300-pound Samoan.”

Acosta threatened to sue, and managed to derail an original and long-forgotten plan to turn the book into a film (which eventually did happen, in 1998, as directed by Terry Gilliam). He argued for a two-book publishing deal for his trouble. Acosta had always wanted to be a writer.

“And that’s how he inscribes Chicano history into that space,” Rodriguez said.

“Oscar was educated, he was entitled, he wasn’t gonna go on no hunger strike, he was no martyr,” Rodriguez added. “He was not engaged in the politics of pleasing. He was not going to be anybody’s mascot. He rejected those kinds of maneuvers.”

“He was joyful.”

His Wife, Socorro

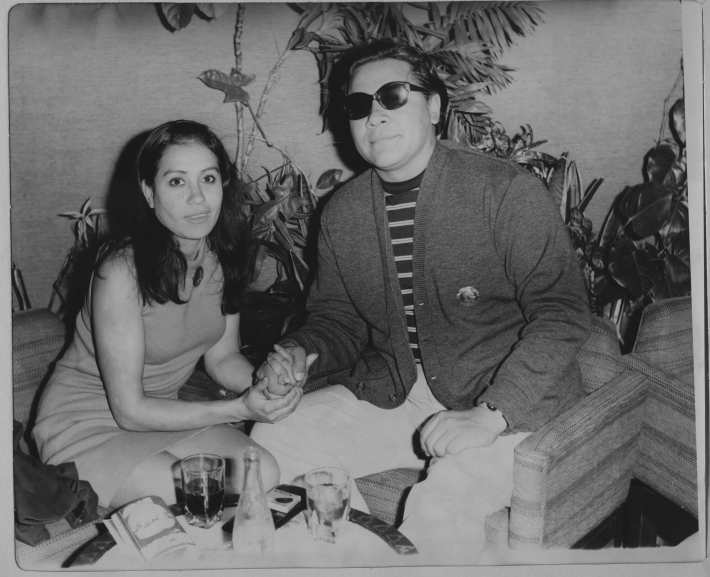

The film’s second key revelation is the depth and complexity of Acosta’s relationship to Socorro Aguiñiga. She was a paralegal, a folklorico dancer — a powerful petite activist who introduced Acosta to many of the key figures in the Chicano Movement. They married.

“I think it was important to give her voice. She was a very strong Chicana activist,” Sotomayor said. “She was the one who introduced Oscar to the leaders of the movement. She was already well connected.”

The fate of the Brown Buffalo is perhaps one of the great still unsolved mysteries in pop culture today.

Toward the end of his career, the film shows, Acosta grew more radicalized, and seemed to both infuriate and inspire the movement around him. He often rejected payment for his defense work, and seemed to have constant troubles with money. Drugs and alcohol consumed him.

Then, in almost mythically fictional fashion, Oscar Zeta Acosta disappeared, in 1974, after last reporting to his son that he was in Sinaloa. The film leaves open the suggestion that he might have been involved in a drug deal that went bad. His whereabouts and the cause of his presumed death remain un-investigated and unknown. This makes the fate of the Brown Buffalo perhaps one of the great still unsolved mysteries in pop culture today.

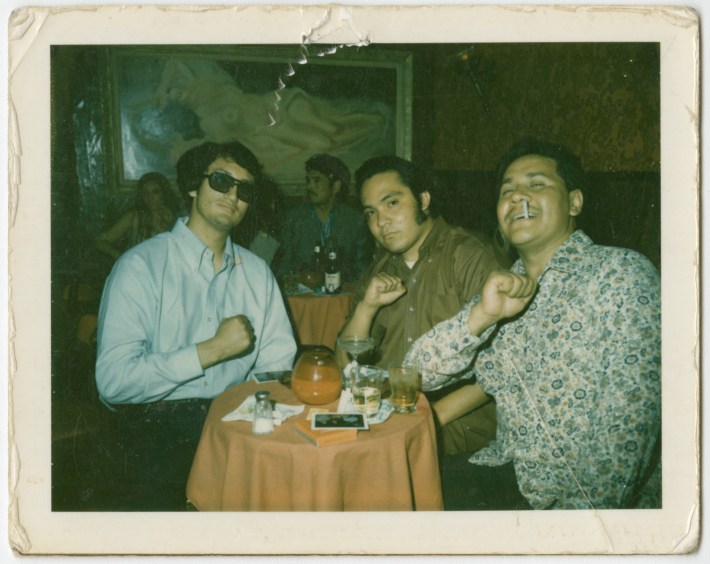

Rodriguez said he wanted to fully depict the variety of relationships and transformations that Acosta carried throughout his life. He described Thompson and Acosta as having something of a competitive bromance.

“They were obsessed with one another, because they were both extreme, and both bright, and both ambitious, and both wanted to be symbols of rebellion in some way,” he said.

“He could be a little overweight, he could be a little cochino, he could be pleasure-seeking, occasionally drunk, and he could still get it on, and throw some chingazos,” Rodriguez said. “Oscar is a great American mestizo.”

Earlier this year actor Benicio del Toro joined as executive producer on the PBS Acosta film. Del Toro played Dr. Gonzo in the 1998 film adaption of Fear and Loathing, a coincidence that happily suggests the Brown Buffalo could be due for a fictional re-take — one where the big ugly brown character is protagonist and no longer sidekick.

The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo is being aired along with a podcast series, available at https://www.brownbuffalofilm.com/.