Almost exactly halfway through the exquisitely nightmarish, enigmatically labyrinthian descent into the nihilistic urban hellscape that makes up David Fincher’s masterful thriller, SE7EN, the film’s two protagonists sit at a table inside a corner pizza joint.

The mild-mannered Detective Somerset (Morgan Freeman), an erudite police veteran who’s on the verge of retirement, and his younger, gung-ho partner, Detective Mills (Brad Pitt), pool together whatever cash they have in their pockets to acquire some backdoor information from the FBI, information that may lead to an elusive and highly methodical serial killer who carefully scrutinizes his victims by way of the seven deadly sins.

The pizza place, mostly lit by whatever available light is able to penetrate the perpetual sheets of rain outside, could arguably be in any large metropolis.

However, one inconspicuous piece of set dressing suggests otherwise.

A disposable paper coffee cup in a blue, yellow, and white color scheme that also features the Parthenon sits on the table in front of Mills. It’s a knockoff of the iconic “Anthora” coffee cup that has for decades been synonymous with New York City diners, delis, bodegas, food carts and coffee shops.

Additionally, Mills’s wife, Tracy (Gwyneth Paltrow), confides in Somerset that moving to this city from “upstate” has been a tough transition.

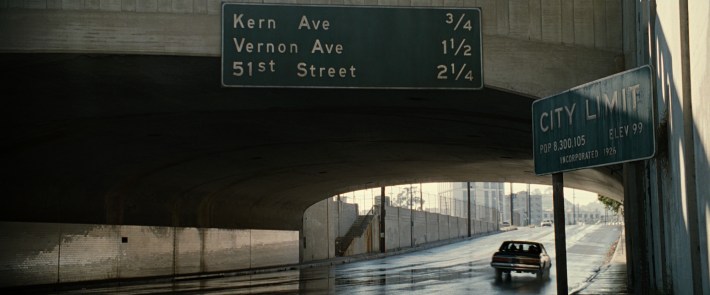

When we mention these minute details to SE7EN location manager Paul Hargrave, he’s quick to interject that New York wasn’t the inspiration behind the nondescript setting of the film.

“It was always understood to be an unnamed Midwestern city. That was the extent of the geolocation of what we were doing,” says Hargrave, who was born in Cleveland and grew up in South Florida before attending the University of Texas and eventually moving to L.A.

However, native New Yorker and four-time Oscar-nominated production designer Arthur Max feels otherwise.

He tells L.A. TACO, “If you look at the sets of SE7EN, they’re all, as far as I was concerned, based on my New York experience. But nobody wanted to come out and say that.”

“I was born and raised in Manhattan, and then moved out to the suburbs briefly and lived for a time in Long Island City. All of that cumulatively helped me design the movie,” says Max, who, as a child, also spent a good deal of time with his grandmother in East Harlem, and, as a college student, lived in a rat-and-cockroach-infested apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

This divergence of perspective is exactly what makes the weathered, timeworn, and oppressive setting of SE7EN so visceral and frightening, and yet alluring at the same time; it can be any city that one’s personal experience or imagination might evoke…

Any city but the one in which it was filmed, that is.

“What David said is, ‘It’s not L.A.,’” says Max. “We were trying to achieve a generic, non-specific or very urban, decaying culture where nothing worked properly and everything was breaking down, including society.”

“It's kind of unusual that it's so intentionally unnamed,” says Hargrave. “I thought that that was always kind of a brilliant stroke, that it just kind of added to the mystique of it.”

The methodical and highly conceptual visual prowess for which Fincher is well known has made him one of the most copied directors of the last three decades. So, it’s no surprise that for about twenty-plus years following the release of SE7EN, Hargrave fielded numerous inquiries from directors, DPs and location managers asking one question:

Where was the film shot?

“People found it hard to believe that that was Los Angeles,” says Hargrave, who, subsequent to SE7EN, worked as the Executive Location Manager at Propaganda Films, the production company co-founded by Fincher, until it closed in 2001.

But, of course, it was Los Angeles, and it was the first in an unparalleled oeuvre of films for which Fincher would double L.A. for other places.

SE7EN’s filming locations ranged from the aforementioned pizza place, shot at the long-gone New York Pizza Express on the corner of Hollywood and Vine, to the bungalows at the iconic (and also no-more) Ambassador Hotel. Other locations included Linda Vista Hospital in Boyle Heights and the rust-tinted desert of Lancaster used for the film’s shocking and unforgettable climax.

“I think the only thing that kind of gives it away, or is kind of disjointed, is at the end when we go out to the desert,” says Hargrave.

“I very sarcastically kept calling it the deserts of New Jersey,” says Max, “because it was just a very big leap. How do you rationalize that? I could never do it, but it worked very well, and I don’t think anybody really questioned it.”

But the devil’s playground of SE7EN was predominantly focused in downtown, largely in the Historic Core.

“Downtown in the ‘80s and ‘90s was pretty shitty,” says Hargrave. “It was great for filmmaking, because you could go down there and you could really do anything you wanted to do, but it was horribly unfortunate in terms of the people that were denizens of that area. A lot of it, unfortunately, is still exactly the same. But it was bad.”

Before downtown’s renaissance of the early 2000s, places like the Giant Penny Building or the Pacific Electric Building were largely empty.

“They were raw and nobody wanted them at the time. Businesses were going bankrupt left and right. Downtown, in general, was in decline, so it was very ripe,” says Max.

“Those buildings were just so available because there was nothing going on. You didn't have to displace,” says Hargrave. “There was just vacant, vacant, vacant.”

(Hargrave credits longtime Fincher location manager Rick Schuler for finding virtually all of the locations featured in SE7EN. Schuler could not be reached for comment.)

The amalgamation of neglected, early twentieth century architecture, classic detective wardrobe right out of a Raymond Chandler film, and boxy sedans from the ‘70s and ‘80s establishes a timeless, patinated aesthetic that draws from the groundbreaking Los Angeles sci-fi classic, Blade Runner (1982), directed by Ridley Scott.

“There’s a good Yiddish, New York expression: it was a mishmash of cultures and time frames. We tended to study films of that genre, Blade Runner to a large degree,” says Max, who has worked on sixteen feature films with Scott beginning with G.I. Jane (1997) and continuing through last year’s Gladiator II (2024).

SE7EN is also among a handful of films from the mid-to-late ‘90s - though SE7EN is arguably the most influential - in which the filmic environment is composed of a neo or tech-noir wasteland of urban decay that also harkens back to Blade Runner. This concept of a crumbling society within an oppressive megalopolis is infused, to varying degrees, throughout films like The Crow (1994), Strange Days, (1995), 12 Monkeys (1995), and Dark City (1998).

“There was so much hatred and resentment and bitterness about the inequity of the society,” says Max of the latter half of the twentieth century. “It was a collision of culture and the loss of the authentic.”

He adds, “By the time you get to the ‘80s and ‘90s, when there was so much crack and coke and heroin all over the place, that was kind of the world we were getting into. So, these films reflected that, I think.”

The never-ceasing rainfall featured in SE7EN certainly suggests that the film is not set in L.A.. Even in the rare instance the sun makes its way around large canvases that were rigged across entire city streets by way of firing ropes from crossbows between buildings, the atmospheric perspective created by a sun shower almost suggests the burning of acid rain or the discharge of noxious gas.

The torrent of rain also creates a translucent curtain of texture, obscuring details of authenticity that may have otherwise hinted at the location, which the production went to great lengths to mask.

“We were very busy trying to cover up the very strong Hispanic influences in downtown,” says Max. “We spent a lot of time covering up signage and graphics, which were in Spanish, to conceal the fact that we were on the West Coast. There was a big effort to create our own kind of emotional geography, as it were, of a failed urban environment where everything was going wrong and breaking down and nothing worked properly, including government and society in general.”

To mark the 30th anniversary of SE7EN, released in theaters on September 22, 1995, L.A. TACO asked Max and Hargrave to reflect on shooting at some of the film’s downtown L.A. locations.

Somerset meets Mills

We are introduced to Detective Somerset inside a dark, grungy apartment in which a man lays facedown on the floor in a pool of his own blood. We quickly learn that the veteran cop is inquisitive and uses his intellect to survey a crime scene.

His new partner, Detective Mills, haphazardly shows up on the scene, and the cops take their discussion to the street, where it’s pouring rain and a number of the storefronts are shuttered. Somerset, who is soon retiring, is puzzled by Mills’s request for reassignment to this city.

“I’m certain that was day one of filming,” says Hargrave, “because they wanted to keep things in continuity for the characters. And it was the first time that they got together.”

The scene was shot in front of a string of stores along San Pedro St on the edge of the Flower District.

“I remember a lot of accordion grill, storefront security gates; there were a lot of awnings we opened up and added to with plastic and dirty tarps,” says Max. “I remember the emphasis was on things broken and not working.”

Though the scene doesn’t include any wide shots of the building, Hargrave recalls the location being a great find because of its bay windows on the second floor.

“That, too, goes back to these things being so not L.A.,” says Hargrave. “Unless you really, really have a deep knowledge of downtown, you go, ‘Well, that's not Los Angeles. We don't have buildings with bay windows. That's San Francisco.’”

744 - 746 San Pedro St, Flower District

The Fourteenth Precinct

Two years before the critically acclaimed neo-noir classic L.A. Confidential (1997) transformed what is today the Pacific Electric Lofts into a 1950s police precinct, it was used in SE7EN to make up part of a timeworn police station complete with offices, a bullpen, fingerprint lab, and corridors lined with glazed doors and transom lights.

Originally built in 1904 as the famed Huntington Building, it was more commonly known as the Pacific Electric Building, as it once housed the depot for Henry Huntington’s Pacific Electric Railway.

By the late ‘80s, it became a go-to filming location after various ownership changes and dissolutions left the building mostly vacant before being converted into lofts in 2005.

The production had total freedom there.

For Max, the set he created was a direct link to his teenage years, when he worked as a copy boy for a New York newspaper around 1959.

Max recalls, “The kind of layout of rows of desks with the clutter and the top light and the columns and the water cooler, all of those elements were inspired by that period of New York offices with a big open plan with these big structural columns.”

For the precinct lobby, the filmmakers moved a block north to the Rosslyn Hotel (not the adjacent Rosslyn Hotel Annex, which has previously been cited as the lobby location).

At the time of filming, the Rosslyn was known as the Frontier, named after the Frontiera family who purchased it in the late 1970s.

Known as the Rosslyn Lofts today, the building offers both low-income and market-rate housing.

Max says that the lobby of the 1914 Beaux Arts style building was a perfect space due to the turn-of-the-century moldings, applied plasters, walnut wood, and marble staircase.

Screenshot via New Line Cinema.

The floor tiling was also considered in regard to a scene in which John Doe (Kevin Spacey) deliberately surrenders and is handcuffed while lying facedown on the floor.

“The floors were very good and original,” says Max. “I think it’s that porcelain tile from that era of the ‘30s, because that was indestructible. It’s like the hardest kind of ceramic, and it had great character.”

Today, the lobby has been divided, and the staircase to which Max refers and is so prominently featured in the scene, is sealed off behind a wall.

For the staunch precinct exterior, the production moved to the Arts District and shot what is today the Biscuit Company Lofts, which was built in 1925 as the headquarters for the National Biscuit Company.

Hargrave suggests that the use of three seamlessly stitched together locations is one reason why the film has remained influential.

“If it was slapped together, I don’t think we would be having this conversation,” says Hargrave. “Everything was so intentional and so important.”

Pacific Electric Lofts, 610 Main St, Historic Core

Rosslyn Lofts, 451 Main St, Historic Core

Biscuit Company Lofts, 673 Mateo St, Arts District

The Library

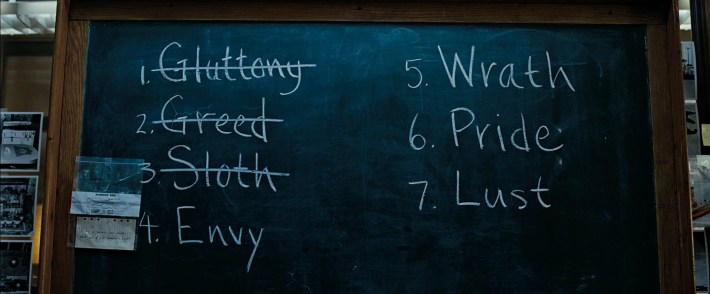

After the body of high-powered criminal defense attorney Eli Gould is discovered in his office, bound and hunched over a stack law books with “a pound of flesh” cut from his abdomen and the word greed written in blood on the carpet, Somerset is convinced the perpetrator is just at the beginning of a string of heinous murders.

In an effort to assist his new partner, Somerset turns to a familiar place of solitude: a cavernous library where he pulls numerous books dealing with the seven deadly sins.

The scene was filmed in what is commonly referred to as the Bank of America building. Built in 1924 as the Hellman Commercial Trust and Savings Bank, it served as B of A’s headquarters from 1930 - 1972.

Though the location - today an event venue known as The Majestic - has hosted dozens of film and TV shoots, SE7EN’s transformation of its main hall into a reverent sanctuary of academia is easily one of the most impressive uses of the space.

Every piece of set dressing from tables to bookshelves was brought into the vacant location, not to mention thousands of books.

“Having rented every book there was for hire in Hollywood from all the prop companies, we still didn't have enough to fill the library,” says Max.

For about a week, Max had a crew of two-dozen people laboriously mass fabricating and labeling prop books according to the Dewey Decimal System.

The final result is a set of such immersive depth and magnitude that no matter where the camera points, Somerset is fully enveloped by a staggering sense of worldly knowledge.

“Today, you probably would have dressed half of that space,” says Hargrave, “and then just VFX everything else that you saw deeper.”

Bank of America Building, 650 S Spring St, Historic Core

Victor’s Apartment

When fingerprints discovered in Gould’s office point to a career criminal by the name of Victor, SWAT descends upon the perp’s last known address.

Howard Shore’s brassy score pulses as police brazenly ascend multiple flights of stairs before breaching Victor’s maze-like apartment. They find it filled with thousands of pine tree air fresheners and eventually discover Victor, near death, tortured and bound on a bed with the word sloth scrawled upon the wall.

The apartment was filmed in the vacant penthouse of one of downtown’s oldest commercial buildings. Constructed in 1895 on the corner of 3rd and Broadway, it has various monikers including the Irvine-Byrne Building and the Pan American Building, but it is perhaps most well known as the Giant Penny Building, a nickname attributed to the popular five and dime store that occupied the ground floor from 1958 - 1998.

The location was, logistically speaking, less than ideal.

“Pigeons had been roosting in there for who knows how long, and there was pigeon shit everywhere,” says Hargrave.

The level of toxicity from the bird droppings was off the charts, so Hargrave had to call in an asbestos abatement team before the crew could begin to work in the location.

The building was also structurally deteriorating, Max recalls, resulting in the use of steel jacks to reinforce parts of the floor.

“But it had, because of all that neglect, so many layers of texture and decay,” says Max. “It was fantastic.”

Hargrave says, “It just added to that blighted, urban feel we were after.”

Giant Penny Building, 253 S Broadway, Historic Core

The Barber Shop and Wild Bill’s Leather

After meeting with the FBI contact at the pizza joint, Somerset and Mills wait for the information from the chairs of a vintage barber shop.

The scene was filmed directly across the street from the Pacific Electric Building at the Owl Barber Shop. The Owl had at one time operated 24-hours a day to accommodate the influx of passengers at the Pacific Electric depot. It ceased operating as the Owl in 2004, but the location has remained a barber shop in various forms over subsequent years; today it operates as Saga Studios.

It wasn’t simply due to proximity to the Pacific Electric Building that the location was chosen.

“That block of 6th Street was one of the handful of blocks that could play for anything,” says Hargrave. “We would always use that for New York, for Chicago.”

A couple of doors down, the filmmakers created Wild Bill’s Leather, a custom fetishist leather shop, in a vacant storefront.

117 & 123 E 6th St, Historic Core

John Doe’s Apartment

Once in receipt of the solicited FBI records, Somerset and Mills head to the apartment of John Doe to see if he might be their suspect.

The apartment building is the pièce de résistance of locations featured in SE7EN.

Built in 1906, with additions in 1911 that included the property’s famed Palm Court ballroom, Fincher’s masterful use of the Alexandria Hotel during a nearly seven-minute foot pursuit emulates the twisted mind of the killer who resides there by exploiting the location’s complex labyrinth of corridors, mezzanines, stairwells, and apartments.

“That was a real kind of treasure trove, that hotel, in that it was scheduled, I think, for a remodel, and they didn't have any problem with us doing whatever we wanted,” says Max. “What I loved about the Alexandria is it was very kind of pre-war and it had in the bathroom the old porcelain octagonal tiling in black and white that my grandmother's bathroom had in East Harlem, and it had the thick layers of paint from many, many re-paintings that built up.”

Max also gushes over the building’s skylights, air shifts, ornate black-gloss fire escapes, broken reinforced safety glass, and a lavish plaster-coffered ceiling on the mezzanine level.

“The authenticity that it gives you to be in a real space and be able to shoot 360-degrees and up and down, floor to floor, you just can’t replace that,” says Hargrave, who remembers the Alexandria as a challenging location.

“It was all itinerant housing,” he says. “The characters that we had, the situations, and all types of people with their own conditions and problems.”

“You had a lot of characters inhabiting that hotel that were used as extras,” says Max. “As the chase progressed, people were poking out of their rooms.”

The bleak, sinuously disorienting apartment of John Doe, filled to the brim with books and notebooks, Christian symbolism, trophies from his murders, and home-developed black-and-white photographs, was created inside the Alexandria by partially knocking down the walls of three adjacent units, says Max.

Hargrave says that the final piece of the chase in which Mills is assaulted by John Doe in the rear alley of the hotel is also atypical of Los Angeles.

“I can’t think of another L-shaped alley like that,” says Hargrave. “And that’s also what kind of messes with people’s minds. The alleys in downtown L.A. are all bone straight between this street and that street.”

Today, the Alexandria Hotel, which was a Green Book site in the 1960s, is an affordable housing property that boasts elegant event spaces on the lower levels.

Filming is still welcomed, but the neglect of time that once attracted the filmmakers of SE7EN has all but vanished from most parts of the building.

Max concludes, “It was a very, very valuable location that I think you couldn’t find anymore downtown.”

501 S Spring St, Historic Core

Follow Jared on Instagram at @jaredcowan.