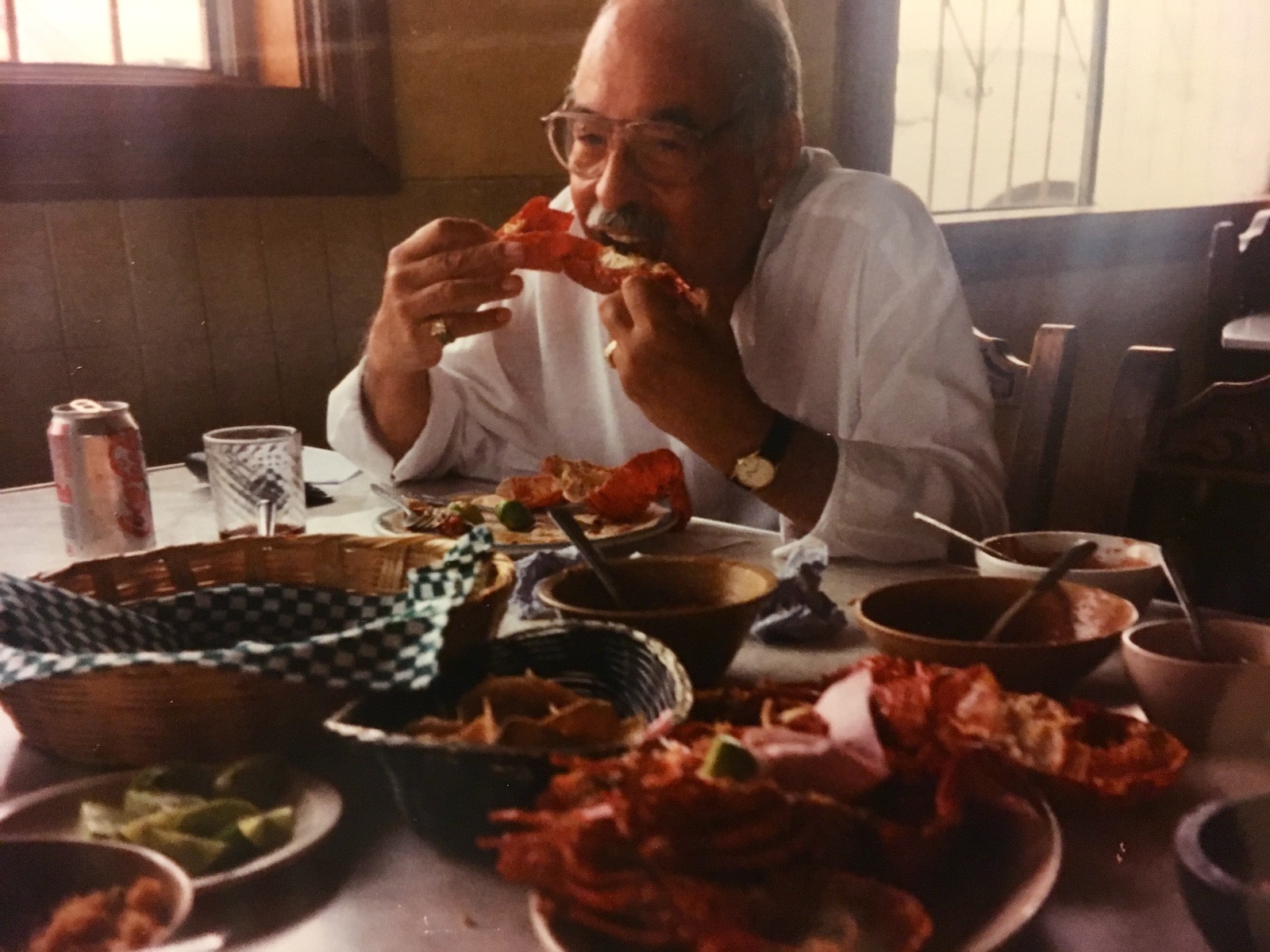

"I can’t drink anymore, and I can’t smoke anymore. I need a vice!” pleaded my grandpa Tom Garcia when we caught him one day with a half-dozen box of donuts. Food was one of his favorite sources of pleasure, albeit a costly one. When he turned 80, my grandpa sensed his imminent death. So he requested, no, demanded that we continue to eat his favorite foods. He left us explicit instructions before he died: “Every so often, have Tommy’s Burger for me, and Olvera St. Taquitos [at Cielito Lindo], and a French Dip at Philippe’s.”

His instructions were incomplete, though. At the top of his list should have been Puerto Nuevo-Style Lobster, the one meal that most reminds me of my grandpa.

From East L.A. to the Baja Coast

Before Las Vegas or Palm Springs, Tijuana used to be Los Angeles’ go-to weekend getaway. In the 1920s, during the U.S. Prohibition era, Angelenos used to cross over to enjoy the glitzy casinos, ornate hotels, and fine dining. Tijuana or Rosarito weekend getaways have become second nature for many Southern California residents. “I remember going, and it seemed like all of El Sereno was there,” read someone who commented on a photo I posted of Puerto Nuevo in an East L.A. Nostalgia group on Facebook.

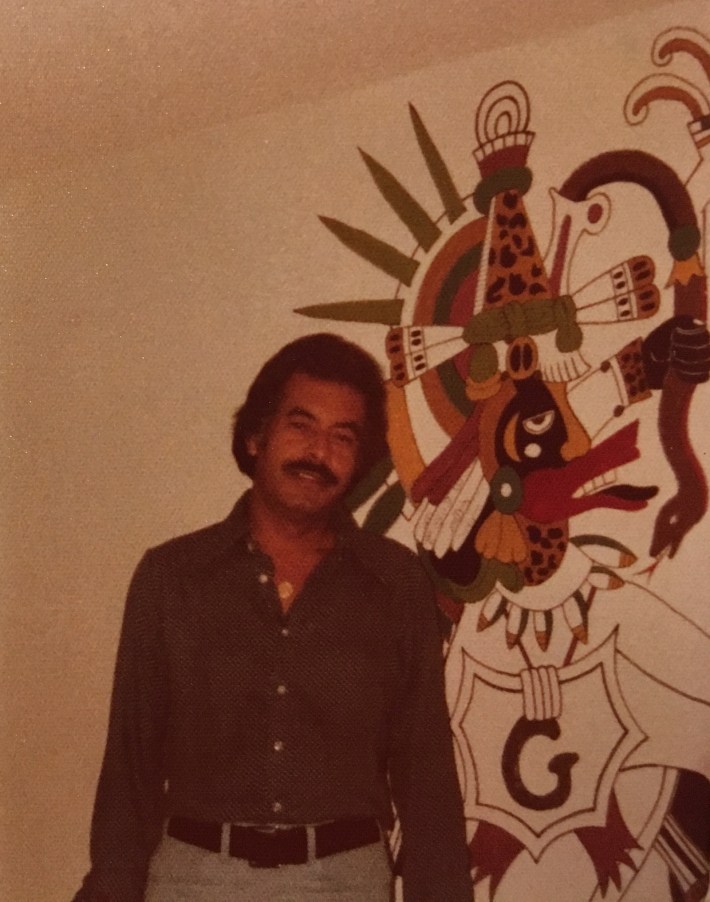

Our family trips down to Baja started in 1962, the year my grandparents got married. My grandpa Tom Garcia, whose mother hailed from Chihuahua and father was an umpteenth generation Californian, met my New Mexico-born grandma Virginia Trujillo in East L.A. After a small civil wedding ceremony in March 1962, they decided on a whim to honeymoon in Baja, California. The trip started at the Hotel Caesar’s on Tijuana’s Avenida Revolución and ended in Ensenada; it was so lively that they celebrated every anniversary in Baja, California.

These Baja trips increased when my grandpa Tom enrolled in an undergraduate program in business administration at Cal State Los Angeles. As a veteran, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill and became the first in his family to receive a Bachelor’s degree, and eventually, a Master’s in Business Administration. The only thing in the way of his studies was his active social life.

“Every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, we had company,” recalls my grandma Virginia. Aunts, uncles, in-laws, and cousins stormed their Pico Rivera home on the weekends. My grandpa realized that he had to get away to focus. So they thought of where their four kids could keep busy while my grandpa could study and the first place to come to mind was Rosarito Beach.

On these trips, locals urged my grandparents to eat in Puerto Nuevo, a small port town between Rosarito and Ensenada. After their first visit to the small fishing village where they dined on lobster in local families’ private homes, they were enamored with the experience.

Ask any relative in my family about Rosarito, and they will automatically bring up Papa Tom.

“My dad put chile on everything, and he made sure we all dressed the lobster the way he liked it. ‘Try this,’ he’d say,” remembers my uncle Tommy. “In those days, they would serve endless trays of lobster all-you-can-eat. When you’re in the Mexico state of mind, you can eat the lobster at Puerto Nuevo like chicharrones,” he reminisces. “Those are some of the happiest memories I have from my life.”

Puerto Nuevo Lobster

My inaugural trip to Rosarito was in 2001 when I was ten years old. For most of my cousins and me, it was our first trip outside of the United States. A chance to test out our few words of pocho Spanish. Our first encounter with “the motherland.”

The only problem...I refused to eat lobster when we finally reached our pilgrimage stop in Puerto Nuevo. I was disgusted when I saw the lobster still had black beady eyes attached to their fried, buttery heads. Besides, I grew up in land-locked Arizona and was not accustomed to seafood. So I feasted on the endless rice, beans, and colossal flour tortillas instead.

When drug-related violence along the border increased in the late 2000s, these trips came to a sudden halt. My grandparents stopped traveling to Mexico for about ten years. They had heard stories in the media of violence along the U.S.-Mexico and grew tired of the mordidas (bribes) at the frequent patrol stops.

Did I miss my chance to eat Puerto Nuevo lobster?

I wouldn't allow that.

So in 2013, emboldened as a recent college graduate and employed adult, I decided to break my family’s self-imposed “Do Not Travel” to Mexico rule. One day, I suggested to my grandpa, “let’s go to Rosarito!” and of course, he quickly agreed. It turns out he just needed a travel buddy.

As soon as we had drinks, my grandpa ordered for the table. My lobster baptism was about to begin. My grandpa showed me that the best way to eat it, of course, is as a taco. He instructed me to slather a layer of beans and rice into the piping hot flour tortilla and then gently scoop the sweet lobster meat into the tortilla.

On a bright Sunday morning of early November 2013, my good friend Chris, my grandpa, my grandpa’s nephew Chuy, and I piled into my tiny Honda Civic. After a near fender bender on the drive through Tijuana (I always have anxiety behind the wheel in Mexico—or anywhere for that matter), we made a quick stop for beers at the Beach Comber. My grandpa, to no one’s surprise, reconnected with an old bartender friend he knew from decades past.

People who frequent Puerto Nuevo are loyal to their favorite restaurants: Sandra’s and Ortega’s are consistent favorites. That day, I learned my family is loyal to Puerto Nuevo Restaurant #1, most likely for no good reason except that it’s the closest one to Puerto Nuevo’s village entrance.

As soon as we had drinks, my grandpa ordered for the table. My lobster baptism was about to begin. My grandpa showed me that the best way to eat it, of course, is as a taco. He instructed me to slather a layer of beans and rice into the piping hot flour tortilla and then gently scoop the sweet lobster meat into the tortilla. Finally, I had to top the taco with a layer of salsa and voilá. Just one bite and I was hooked.

Before this meal, I thought of lobster as a luxury food meant for fancy people who ate Surf and Turf at overpriced steakhouses. But Puerto Nuevo taught me to say a la chingada to that idea.

There’s nothing like a massive bowl of beans on a table next to the lobster to humble you. To prove to you that Mexicans know how to enjoy food. Hell, to remind you that you are Mexican. Let’s never forget: Lobster has been a traditional food source for Indigenous peoples across the Americas for generations. Also, lobster was once a food associated with poverty.

After our mal del puerco, a specific type of post-feasting body crash that comes after eating pork, which in this case came in the form of the ultra-savory lard folded into the handmade chewy flour tortillas and silky beans, we drove through Tijuana. We made our way towards the border, where we inched along for four hours to re-enter California. But we didn’t care. We bought churros from street vendors, swapped stories, sang along to music on the radio. We were in Mexico!

I know he’d be proud of us for cooking, eating, and por convivir in his honor.

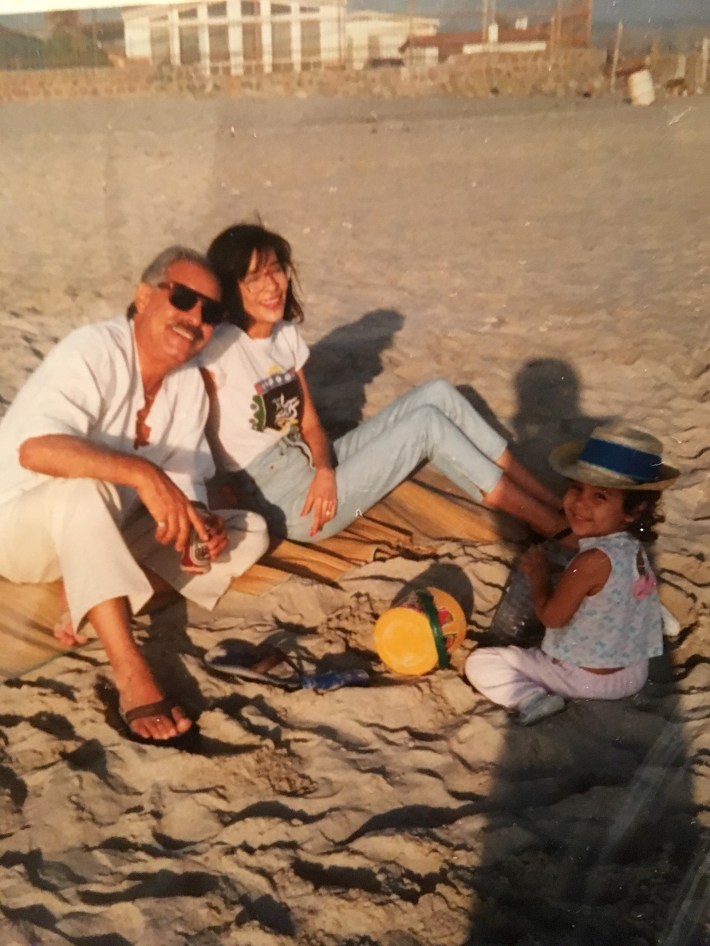

This seedling of a trip bore fruit. A few years later, my entire family got organized and took my grandpa to Rosarito for his 79th birthday, one of his last. He was surrounded by his grandchildren, great-grandchildren, nephews, nieces, and friends. He ate his favorite meal and sang his heart out with the circling tríos. This is what made him the happiest. He measured success by the amount of love, family, and friends he had. And of course, good food. He often reflected on his life in his final years and said: “Not bad for a poor Mexican!” with a huge grin on his face.

Food and death

Many cultures honor their dead with food. Egyptians buried their pharaohs with their favorite foods. Mexicans adorn altars with their departed loved ones’ favorite meals and libations for Día de Muertos. Thanks to my grandpa, now I know why. Food is our spiritual connection to those who cooked for us, fed us, and nourished us with sustenance and cultural heritage.

A few weeks ago, on the eve of the fourth anniversary of my grandfather’s death, my sister and I suddenly started craving Puerto Nuevo-Style lobster. He must have nudged us. We prepared the lobster at home with a recipe by Playa Amor’s Thomas Ortega (found in L.A. Mexicano). We attempted to recreate the Puerto Nuevo experience: we listened to trío boleros, drank a few beers, and made a buttery lobster feast. And while crucial elements were absent—the beachside views, the live music, my grandpa—I know he’d be proud of us for cooking, eating, and por convivir in his honor.

I am indebted to my Papa Tom for this lobster-eating tradition and for my love of food and fiesta. One day, I hope to continue this tradition with my own family, si Dios quiere. For now, I hope to visit Puerto Nuevo for my 30th birthday later this year.

I pray to him whenever I feel stuck: in a dead-end job, in a relationship gone sour, or any other fork in the road of life. I ask him for his guidance and listen for his advice. His answer always starts with a request: “Have a delicious meal—for me.”