Since Arnold Schwarzenegger took on the titular character of 1987’s "Predator" in the dense Central American jungle, members of the highly intelligent extra-terrestrial race of inherently relentless trophy hunters have, through its handful of sequels and mashups, visited the frigid ice shelves and frozen plains of the Antarctic ("Alien vs. Predator," 2004), the quaint streets of small-town Colorado ("Aliens vs. Predator:" Requiem, 2007), the lush rainforests of Mexico ("The Predator," 2018), the vast expanse of the Northern Great Plains ("Prey," 2022), and distant, largely organic alien worlds.

But in the franchise’s second installment, the volatile and monstrous decimator-of-all-species sets its infrared-seeing sights and extraordinarily advanced weapons system on a man-made and highly-populous urban environment, making it an anomaly within the "Predator" cinematic canon.

Released on November 21, 1990, "Predator 2" is set in the year 1997, and Los Angeles is a muggy, suffocating sweat-box with temperatures rising well above 100-degrees on a daily basis.

Setting the stage for its somewhat bonkers plot is a raging L.A. drug war between rival gangs of Colombians and Jamaicans, neither of which have had dominant gang strongholds in L.A. Apropos of nothing other than to conjure up a stereotype of Caribbean spiritual practices, the latter gang calls itself the Jamaican Voodoo Posse. (The spiritual folk religion of Obeah, not Haitian voodoo, is practiced in Jamaica, though illegal.) Drawn by extreme conflict and heat, a new Predator—the one from 1987 killed itself with a self-detonating, nuclear-strength explosive device attached to its arm—hones in on downtown L.A.

Caught in the middle of the gang war is Lieutenant Mike Harrigan (Danny Glover), an 18-year veteran of the LAPD who’s known for violent, insubordinate and obsessive-compulsive tendencies. In Harrigan, the Predator sees his ultimate Los Angeles trophy.

Though set in the near future, "Predator 2" feels somewhat timeless.

Glover’s baggy suits are indicative of ‘90s style trends and also harken back to classic L.A. gumshoe films of the ‘40s and ‘50s. Likewise, high-contrast film noir lighting techniques are sometimes on display. Beat cops drive 1990 Chevy Lumina APV’s while many other vehicles that appear on screen are out of the ‘70s. The comic book color palette and over-the-top, adrenaline-pumping action sequences are right out of the excessive, yayo-fueled Hollywood of the preceding decade.

In fact, because much of the film was shot at night, "Predator 2" location manager Lisa Blok-Linson told L.A. TACO in a recent interview that cocaine played a surreptitious part in getting the film in the can.

“It was a crazy time to make movies,” she adds.

Recollections of the production’s armed private security guards smoking crack in an alley near one of the film’s locations, or the same security team being forced to the pavement by LAPD officers with guns drawn punctuate our discussions with Blok-Linson and her location associate and scout, Jim Vatis. Stories of dead bodies, drug addicts, alcoholics, large rodents, and toxic chemicals seem to incessantly overshadow the creative work that the small locations department put in on "Predator 2."

Nevertheless, the skillfully curated assemblage locations—largely in and around many of downtown’s derelict historic properties of the day—conveyed a fractured, dystopian future, something the film’s production designer, the late Lawrence G. Paull, achieved so masterfully within the same downtown geography eight years earlier with "Blade Runner" (1982).

A native New Yorker, Blok-Linson says she learned a great deal about Los Angeles, including downtown, while working as a production manager on director Agnès Varda’s whimsical documentary on L.A.’s murals, "Mur Murs" (1981).

Blok-Linson says, “Downtown L.A. was our backlot. We did whatever we wanted. We’d get permission for some things, but we could have done anything and no one would’ve stopped us. It was nuts. And you can’t do that anymore.”

“There was less red tape,” says Vatis. “Downtown was desolate, especially at night. There were a few bars and restaurants that were scattered throughout down there, but they were the brave ones.”

“Besides it being derelict, it was also a time of huge drug abuse down there,” says Blok-Linson. “There would be hundreds of people roaming around the streets at night like zombies on crack.”

At first, the location manager was hesitant to suggest that the setting of Los Angeles lends artistic merit to "Predator 2."

“If you want to turn it into an artistic vision, I think you’re stretching,” says Blok-Linson.

She believes the film was set in L.A. simply due to the practicality of it being the production capital of the world, before other states and countries began luring away the industry with valuable tax incentives.

She adds, “You’re in an urban environment. You could be anywhere, really. Once the sun goes down, who the hell knows where you are, honestly. You’re in an alley; you’re on top of a building. There’s nothing that really screams that you’re in L.A. except that we know we’re in L.A.”

As it happens, from 1989-1990, a four-issue comic entitled "Predator: Concrete Jungle" was published. It was a sequel to the first film and saw the brother of Schwarzenegger’s character, a hardened and chiseled NYPD detective, in the middle of a turf war on the scorching hot streets of New York City. The cop eventually goes up against a Predator.

A number of "Predator 2"’s story elements come from the pages of the comics; certain frames of the film are almost shot-for-shot recreations of the comics’ illustrations.

While there’s truth to Blok-Linson’s straightforward assessment, "Predator 2" capitalizes on a contemporary Los Angeles in a state of flux.

Sleek, mirrored skyscrapers are seen dwarfing the U.S. Bank Tower by nearly double its height in nighttime matte shots of downtown’s upwardly expanding skyline, a comment on the oversaturated and largely failed downtown construction boom of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.

A grisly, strobe-lit subway sequence is telling of a city about to dedicate its first passenger rail line in nearly thirty years.

Upon further conversation with Blok-Linson, she acquiesces some about the role of which L.A. played in "Predator 2"

She says, “It’s really about the heat and global warming, which is kind of ahead of its time in that concept (but I don’t think anyone took any of that seriously anyway; they still don’t). Everyone’s sweating balls. People come because of the weather; we get very little rain. L.A. seemed like a likelier place for that to happen.”

“This was not going to work in London or Houston or any other big city,” says Vatis, who also hails from New York and lives there today. “I think it was well suited to L.A. It fit the storyline, how it was going through a 110-degree heat wave at the time.”

Vatis adds that the authenticity of locations, which were, in reality, often found in hostile, unsound environments, supported the concept that Harrigan had an innate ability to fight and survive under any circumstance, a key component by which a Predator chooses its prey.

Prior to our phone interview with Blok-Linson, email correspondence with the location manager ranged from highly promising—she wrote that our curiosity on the subject would “pay off”—to somewhat bewildering. Questions about confirming locations were answered with responses like not sure about this, I beg to differ with you, I don’t think so, or flat out no, even though L.A. TACO had closely compared images from the film with Google maps.

In all fairness, "Predator 2" is thirty-five years old, but it started to feel like some of the film’s locations were just as elusive as the Predator itself.

After we sent Blok-Linson some screenshots and Google map links and she inquired with Vatis, who still has records from the shoot, we were finally in sync.

Vatis’s records also confirmed locations from the film that have not been previously reported.

“You have the most accurate [location] information there will ever be as far as this movie is concerned,” says Blok-Linson.

Featured in the film are locations including the Federal Reserve Bank Building at the corner of Olive and Olympic as the exterior of the Alvarado Precinct, where Harrigan and his team are based. Its corresponding interior was shot at the Walnut Building in the Arts District. The Los Angeles Stock Exchange Building on Spring Street appeared as the exterior of the LAPD Administration Building. Storefront windows of a clothing shop at Hill and Olympic were tellingly transformed into those of taxidermy store. Though hard to tell due to the tight framing, the mainstay Cypress Park bar Footsie’s was employed briefly for a scene in which Harrigan confers with a member of his team, Detective Jerry Lambert (Bill Paxton), about their next moves.

“You’re lucky because, really, you’ve got the whole enchilada,” Blok-Linson stresses.

But to mark the 35th anniversary of the most wildly excessive installment of the Predator series, L.A. TACO honed in on the places where the Predator itself was present, cloaking device and all.

The Opening Shootout

Along with "The Big Lebowski," Predator 2 opens with what is arguably one of the greatest trick reveals of Los Angeles ever put on film.

A fast-moving aerial shot tracks over brown hills lined with palm trees and other vegetation as Alan Silvestri’s tribal-inspired score pulses throughout. Just when we think we’re still in the jungle from the first film, the camera rises from above the Elysian Reservoir to reveal smog-covered downtown Los Angeles.

From there we’re throttled into the city via the iconic infrared point of view of all Predators and dropped into the middle of a brutal shootout between the Colombians and LAPD in broad daylight. A deadly barrage of assault-rifle fire and explosions never lets up. Downtown’s skyscrapers rise in the background.

“It definitely places you in downtown L.A., and we never leave,” says Blok-Linson.

Eventually, our hero, Harrigan, joins the fight to save two downed motorcycle cops stranded in the middle of the crossfire.

While all of this transpires, the Predator watches, carefully choosing its prey.

The entire sequence, labeled “Beirut Street” on construction notes in Vatis’s files, lasts nearly sixteen minutes of screen time.

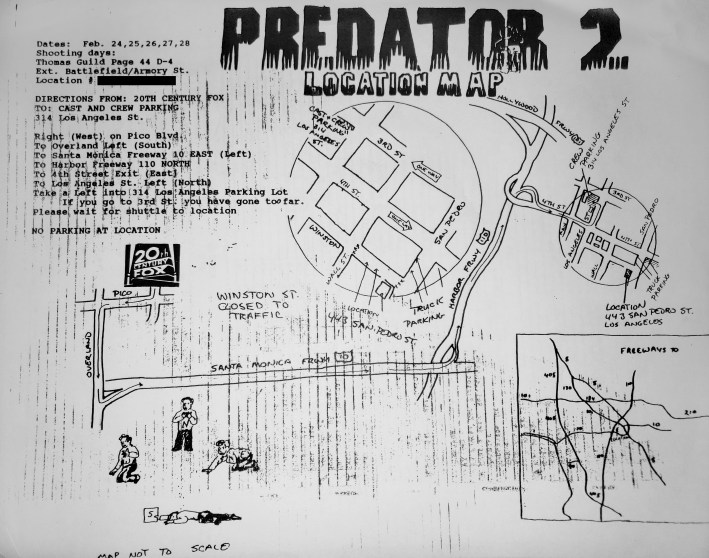

For the street exteriors, the filmmakers used Winston Street between Wall and San Pedro, which also appears in the trailer for the stylish and erotic ‘80s punk-new wave horror picture, "Vamp" (1986). That film was Blok-Linson’s first location manager credit and was shot almost entirely in downtown.

“That was a part of L.A. that wasn’t super busy. It’s the Toy District,” says Blok-Linson.

She recalls this sequence being among, if not the first shot for Predator 2, and it took about a week to accomplish.

“Winston Street had a lot of logistics to it,” says Blok-Linson. “In those days, there was no permit service [like Film L.A.]. We as location people had to navigate the city to get what we wanted.”

This meant researching infrastructure records and presenting them to officials at City Hall in order to pull up a manhole cover and dig into Winston Street for the purpose of installing an air compressor that would launch an exploding police cruiser into the air.

What helped matters, Blok-Linson says, is that a businessman named Sammy Hong owned almost all of the buildings on the block.

“Jim and I were like the ambassadors of the Predator. We got everyone to work with us,” says Blok-Linson. “Filmmaking is seductive. I don’t care who you are. It’s like, ‘Oh my god, they’re making a movie on my street.’”

But Vatis, who may have had the hardest of jobs on Winston Street, has a different perspective.

“Already back then, because L.A. was the hub of filming in the world, you could kind of sense the burnout a little bit,” says Vatis. “Either people had gotten quite savvy and would ask for extraordinary amounts of money, or they were just pissed. There wasn’t a lot of goodwill, especially down there.”

Vatis had to track down the owner of the Panama Hotel, a seedy drug hotspot of the day, the rear of which faces Winston Street. Upon the advice of a cop assigned to the production, Vatis bought a Smith & Wesson 9mm pistol to keep on his person while traversing the area.

Vatis’s biggest task on "Predator 2" was coordinating the arrival and landing of a helicopter on San Pedro Street for the introduction of a mysterious government agency led by actor Gary Busey. Negotiations and coordination involved CalTrans, LAPD, and the FAA.

“That hadn’t been done before, at least not around there during a weekday, daytime, with the beginning of rush hour pending,” says Vatis.

With a slim window of time in which the production was permitted to shoot only two takes, and the closest pre-staging area (for a chopper running out of gas) located fifteen miles away, Vatis had to plead with authorities for a third take when the first two were blown.

Ultimately, officials consented to one more shot.

This all leads to the question: could a scene of this magnitude be accomplished in downtown L.A. today? Again, Blok-Linson and Vatis are of different opinions.

“If you had a shit-ton of money and if you got the right permission,” says Blok-Linson. “But you’d have to do it over the course of consecutive weekends.”

Vatis is more blunt in his assessment.

He says, “Oh, hell no. No, no, no, no, no, no.”

Winston Street between Wall St and San Pedro St, Toy District/Skid Row

The Colombians’ Armory

As the police gain ground, the Colombian gang members retreat into their armory inside the Roger Cowan building, at the time an artist loft space at the corner of Winston and San Pedro. Today, it is the Tailer Lofts apartments.

The filmmakers shot a stunt of El Scorpio (Henry Kingi) falling from the roof of the building and landing on a table set with bowls of salsa and guacamole next to a mariscos truck.

However, the roof itself, where the Predator first appears masked by his cloaking device, was that of a tried and true location of the day.

“Everyone used the Pacific Electric Building,” says Blok-Linson. “At that point, the Pacific Electric Building was just one big, giant empty building.”

Having once housed the depot for Henry Huntington’s Pacific Electric Railway, the building from 1904 went through various ownerships before it was converted into lofts in 2005.

Filming at the Pacific Electric Building was a common practice in the ‘90s, having been featured in films like "The Fisher King" (1991), "SE7EN" (1995), "The Rock" (1996) (on which Blok-Linson also worked), "L.A. Confidential" (1997), and "Face/Off" (1997). Today, filming at the location no longer appears as prolific. Inquiries to photograph the building for this article went unanswered.

Ironically, after the production chose the location, they discovered that the Pacific Electric Building hadn’t paid their power bill.

“In order for us to work there and have anything that functioned, we had to pay their electric bill. And that was thousands and thousands of dollars, but we had no choice. We couldn’t let the crew hump up ten stories,” says Blok-Linson.

Interiors for the LAPD Administration Building were also filmed inside the Pacific Electric Building.

Pacific Electric Building/Lofts, 610 Main St., Historic Core

Ramon Vega’s Apartment

Through a series of jump cuts, we are taken from a wide shot of downtown L.A. into the upscale, open-plan apartment of Colombian drug lord Ramon Vega (Corey Rand).

When the apartment doors burst open, members of the Jamaican Voodoo Posse rush in and string up a naked Vega by his ankles. After Vega is run through with a knife, the Predator takes out all of the Jamaicans.

The apartment interior, designed to mimic Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mayan-inspired textile block houses around L.A., was filmed on a Fox soundstage, but the exterior, including street scenes shot along Ingraham Street, was filmed on the edge of downtown at 1100 Wilshire Boulevard.

“I think we liked it because it was modern. Again, we’re in the future,” says Blok-Linson.

Though pleasing to the eye on the outside, the contemporary 37-story office tower that opened as the WTC Building in 1987 never caught on with tenants.

The building’s 16-floor above-ground parking structure was found to be awkward to navigate; the triangular office floor plans were unpopular.

In 1997, the L.A. Times reported that the building owner, a successful Taiwanese businessman, never adapted his stubborn business practices to a Western marketplace. While fluent in Chinese and Japanese, he did not speak English well, and his insistence on personally signing every lease led to delays and pissed off prospective tenants. He reportedly denied leases after they had been agreed upon by his American leasing director.

Occupancy was never at more than 10%.

Blok-Linson says the set’s layout was based on raw office space at the building, of which there was plenty according to the Times, which also reported that much of the building’s interior was never completed.

“I do remember seeing full floors that weren't finished,” says Vatis.

By 1992, the WTC Building was foreclosed upon; It was converted and reopened as a luxury condos in 2007.

Today, the Chase logo adorns the top of the tower.

1100 Wilshire Blvd., Westlake

Harrigan Meets King Willie

By setting a meeting with the Jamaicans’ mystic leader, King Willie (Calvin Lockhart), Harrigan hopes for answers about who is slaughtering both gangsters and cops, including his right-hand man and best friend, Detective Danny Archuleta (Rubén Blades).

Upon arriving in a darkened, trash-strewn alley, a car door of the Jamaicans’ customized 1978 Cadillac Fleetwood opens and a plume of billowing ganja smoke precedes Harrigan’s exit. After the cop meets with King Willie at the end of the alley, the Predator makes its move on the Jamaican drug lord.

“It was disgusting,” Blok-Linson says of the alley off Broadway and 7th Street. “We had to clean it and put clean garbage in there.”

“I supervised a lot of this shit,” says Vatis in his thick New York accent. “We went in with this water truck and washed everything down. Then we had people come in with disinfectant and spray everything. Then the water truck came again. It was the cleanest it had been in years when we finally got in there to shoot.”

On the making-of featurette, director Stephen Hopkins, who had previously directed "A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child" (1989), describes the crew finding dead bodies under garbage upon cleaning out the alleyways in downtown. This disturbing anecdote is also mentioned in the film’s IMDb trivia.

Vatis, who rewatched the behind-the-scenes documentary prior to our interview, emphatically denies anything like that ever happened.

“I don’t know where this bullshit came about,” he says. “I can assure you that as locations, we would have known about that. We were the first ones whose heads the producers would’ve been looking to chop.” He then mimics the panic that would have come over the walkie talkie: “Uh, locations, we have a dead body here.”

Vatis also presumes that the media would have picked up on a dead body found on a shoot.

Hopkins could not be reached for comment.

Additionally, Vatis dispels the director’s wild claim that the grips were attaching leashes to giant rats and walking them around the set like pets.

It’s possible, however, that Hopkins may have confused a live rat for a dead one that Blok-Linson says the Teamsters, with boredom setting in, dragged around the set scaring women on the crew.

“Very childish shit that happens on a movie set,” she says.

Alley between Broadway & Spring St. and between 7th St. & 8th St.

The Cemetery

Unbeknownst to Harrigan, the Predator tracks him to a cemetery where the strained cop visits the grave of his fallen partner, Archuleta.

Upon leaving the gravesite, Harrigan recognizes a necklace that belonged to his partner hanging from a tree branch. Realizing that he is being followed and taunted by an undetectable adversary, he draws his gun, but comes up empty.

Before speaking with Blok-Linson and Vatis, we were able to ID the cemetery location by cross-referencing discernible names on a couple of headstones with Find a Grave and an early twentieth-century obituary on newspapers.com.

The scene was shot in the southeast corner of the historic Angelus Rosedale Cemetery, founded in 1884 as Rosedale Cemetery.

A few notable interments at Angelus Rosedale are actress Hattie McDaniel, filmmaker Tod Browning, actor and musician Dooley Wilson, and actress Anna May Wong.

Blok-Linson says that the cemetery made logistical sense in its proximity to downtown.

Upon going through his paperwork, Vatis says there was only one stipulation to filming in the cemetery: The filmmakers were not permitted to show names on existing headstones.

“I can understand that,” says Vatis. “Family members not knowing what kind of movie it was or what was going to be featured in that scene. I think it was just out of respect, really.”

If you visit the cemetery, keep an eye out for packs of coyotes roaming the grounds!

Angelus Rosedale Cemetery, 1831 W Washington Blvd, Pico Union

Alameda Street Station

The first Los Angeles Metro Rail line, the Blue Line (A Line), opened on July 14, 1990, after "Predator 2" wrapped production. So, filmmakers traveled to Oakland to capture shots of BART trains traveling through tunnels for a scene in which the Predator takes numerous victims, including Detective Lambert, aboard the supposed L.A. subway. Other parts of the sequence were shot on stage at Fox.

A media frenzy forms on the street outside the “Alameda Street Station”, which was shot along Santee Street in the Fashion District.

This was one of the locations that Blok-Linson initially questioned, thinking we meant Santee Alley, until Vatis confirmed it with his notes.

With a second partner dead and another, Detective Leona Cantrell (Maria Conchita Alonso), seriously injured in the subway attack, Harrigan has had enough, and so begins a chase through downtown L.A. that leads to the film’s climax.

Harrigan pursues the Predator, driving through various alleys before crashing through sheets of corrugated metal outside the L.A. Cornell Building and Santee Passage.

Santee St. north of 9th St., Fashion District

743 Santee St, Fashion District

Eastern Columbia Building

Built in 1930 as the headquarters and flagship store of the Eastern Outfitting Company and the Columbia Outfitting Company, the Eastern Columbia Building’s Art Deco, turquoise terra cotta and gold-leaf facade is a mesmerizing crown jewel among the surrounding monotony of brown and grey hues.

Quickly on the move, the Predator scales the side of one of the city’s most iconic buildings.

“That was a gorgeous building from the uniqueness of the color to the top,” says Vatis. “They were mostly concerned about, of course, any potential damage and the ability of us to repair that. But surprisingly they weren’t too difficult to deal with. I think today there would’ve been more hurdles to jump through.”

The imagery of the hulking Predator in its signature bio-mask and indigenous warrior fatigues, with a victim’s bloody skull and spine dangling from one hand, a retractable spear raised high in the other, standing victorious against the backdrop of the building’s iconic, neon-lit clocktower, is suggestive of a conquering king ruling from a temple mount.

It’s no wonder the image was used for the film’s poster and soundtrack album cover.

The Eastern Columbia Building was converted into offices in the 1960s.

At the time the building was purchased in 2004 and slated to become condos, the L.A. Times reported that the Eastern Columbia Building was about 20% to 25% occupied.

2006 saw the reopening of the building as a 13-floor residential tower.

Recently, the Eastern Columbia Building underwent a major rehabilitation of its striking exterior in which many of its terracotta tiles were clean or replaced.

The building manager informed L.A. TACO that a model of the building is put on display around the holidays. One resident is known to lovingly place a Predator action figure at the top.

Eastern Columbia Building, 849 S Broadway, Historic Core

Redwing Meat Packing Co.

As the Predator climbs the Eastern Columbia Building, Harrigan arrives at the Redwing Meat Packing Co., supposedly located in Vernon. It’s there the cop learns that Busey’s character, Peter Keyes, is the head of OWLF (Other World Life Forms), a top-secret government agency formed in the aftermath of the first film with a directive to study the creature and analyze its advanced weaponry. After weeks of tracking the Predator, Keyes and his team plan to capture it at the meat packing plant, where it feeds every couple of days.

Initially, the filmmakers scouted real slaughterhouses and meat packing plants.

“Those are not pretty places to have to scout,” says Vatis.

“We looked at a lot of that,” says Blok-Linson. “But they’re small and they’re cold. A practical meat packing or refrigeration unit was never going to work.”

The filmmakers turned to what was originally part of the 1904 Edison Electric Steam Power Plant, later becoming the Pabst Blue Ribbon brewery.

In 1982, the 16-acre property was converted into the Brewery Artist Lofts, the artist-in-residence complex in Lincoln Heights that hosts Brewery Artwalk twice a year.

Tucked into the back corner of the property, the industrial brick, concrete, and corrugated metal building used by the production, as well as films like "Internal Affairs" (1990) and "Color of Night" (1994), was ideal, says Blok-Linson.

“It was a big, empty thing,” she says. “There were these catwalks where we could have the Predator walk up and down, and where we could hang the fake meat.”

According to Hopkins’ DVD commentary track, filming inside the meat plant set was difficult due to the “radioactive dust” used to adhere to the Predator, therefore making him visible, requiring the use of oxygen masks. But it didn’t compare in the slightest to what was going on outside the building.

“In those days, the city was flying bug abatement planes—like crop dusters—in formation spraying malathion in downtown L.A.,” says Blok-Linson. “They were coming right across where we were, and there was no place for us to go.”

The state had been spraying the pesticide over communities since the early ‘80s in an attempt to eradicate the Mediterranean fruit fly, or Medfly.

At the time of filming "Predator 2," various cities in the L.A. region passed ordinances in an attempt to curb the spraying of pesticides on residential areas.

In early 1990, Pasadena sent up its own police helicopters to try and ticket state choppers dropping malathion. It accomplished nothing except for perhaps bringing some attention to the issue.

“We didn’t have safety officers. We didn’t have studio people watching us,” says Blok-Linson. “Maybe it was unpleasant for certain people filming inside, but I was more concerned about the cancer-causing agents that were basically being ladled on top of a film crew outside.”

The rooftop of the Redwing Meat Packing Co. was shot a few miles back into downtown at the 1926 Beaux Arts-style Board of Trade Building at 7th and Main. Complete with regal Hippogriff statues adorning the exterior corners of an upper floor, it was there that Glover was harnessed onto the ledge as the Predator dangled from the side.

Brewery Artist Lofts, 1920 N Main St., Lincoln Heights

Los Angeles Board of Trade Building (Ames Lofts), 111 W 7th St., Historic Core

The Predator’s Ship

The chase supposedly continues into the building adjacent to the Redwing Meat Packing Co., the oft-filmed Bank of America Building, also known as the Spring Street Towers. But the interior was split between an apartment set and a hallway at the Frontier Hotel, originally the Rosslyn Hotel and today the Rosslyn Lofts.

“It was a transient hotel kind of thing where people rented rooms,” says Blok-Linson.

Vatis says, “It was not a clean place.”

The grim hotel, however, provided a bit of serendipity for a scene in which Harrigan pursues the Predator to an open elevator shaft that unknowingly leads to the Predator’s spacecraft.

“They happened to have two elevator shafts, one that worked and one that didn’t. How fortuitous was that?” says Blok-Linson. “In those days you didn’t really have the resources. There was no Internet; there was no nothing. To find weird things like that—locating an inoperable elevator shaft was not researchable. So, finding it was magic.”

It’s aboard the Predator’s ship, a combination of matte painting and set built on a Fox soundstage, that the camera picks up a familiar elongated skull in the Predator’s trophy case, suggesting to audiences for the first time that "Predator" and "Alien" take place in the same filmic universe.

After battling the Predator aboard its spacecraft, Harrigan narrowly escapes before the ship takes off through the abandoned train tunnel in which it has been lying dormant.

Harrigan eventually emerges from the tunnel’s mouth, which was shot at the historic Belmont Tunnel off of 2nd and Toluca Street.

Operating as part of the Pacific Electric Railway from 1925-1955, the Belmont Tunnel was one end of a mile-long route that began at the Subway Terminal Building at 4th and Hill Street, which Blok-Linson says the production accessed for the purposes of logistics.

“You want to talk about toxic?” says Blok-Linson. “Walking through those tunnels, in the bowels of the Subway Terminal Building, I’m sure we had concerns like, ‘What the hell is in this thing? What are we breathing?’ I mean, it’s amazing we’re still alive.”

After the Pacific Electric Railway ceased operations along this line, subsequent uses for the Belmont Tunnel included a bunker for storing over 300,000 pounds of crackers during the Cold War and later an impound lot for cars involved in drug cases.

Eventually, movies came along, but the location’s most culturally significant use was that of a concrete canvas.

In 2004, former L.A. TACO editor Daniel Hernandez wrote in the L.A. Times, “Since the early 1980s, the [Belmont] tunnel has been the internationally recognized epicenter of West Coast graffiti.”

Though difficult to discern in "Predator 2"’s nighttime exterior finale, the location’s draw as a graffiti Mecca is evident in a number of other films that shot the tunnel and adjacent Toluca Substation including "Murphy’s Law" (1986), "Colors" (1988), "The Running Man" (1987), "Reservoir Dogs" (1992), and "The Replacement Killers" (1998).

Opened in 2008, the Belmont Station apartment complex incorporated the substation and sealed-off tunnel opening, both of which received historic status in 2004, as part of an outdoor lounge, dog park, and entertaining area.

Bank of America Building (The Majestic), 650 S. Spring St., Historic Core

Rosslyn Lofts, 451 Main St., Historic Core

Belmont Tunnel/Toluca Substation, 1304 W. 2nd St., Westlake

Follow Jared on Instagram at @jaredcowan.

This article reports that it was discovered prior to filming that the Pacific Electric Building hadn't paid its electric bill, which required the production to fork over thousands of dollars to turn on the power. It was actually another nearby location, the Los Angeles Stock Exchange Building, that had no electricity.