Who owns Los Angeles? Who dominates the city? Who has conquered the crawling metropolis? Simply, who has the power?

In a city as tumultuous as LA, the answers to these questions are both complicated and loaded. With no one city center, it’s hard to find sense and commonality in people’s patterns. The many concentrated cultures makes for a fascinating urban experience, but it also turns a “typical Los Angeles lifestyle” into an unfathomable idea.

And yet, an idea of that lifestyle persists. Hikes. Juices. Low, wood-slat fences. Driving. Avocados. How does this idea of Los Angeles exist, despite the variety of lives (and socioeconomic resources and cultures and work habits and living arrangements) within this city’s parameters? Isn’t a singular Los Angeles identity an oxymoron? External perception would lead people to think otherwise, because of one concept: visibility.

The bulk of this city’s economy runs on being seen. The industry at its center measures success on viewership, and the growing creative economy relies on self-promotion and awareness (Instagram followers turned business investment). These economic structures are also the ones people around the country read about and see online and in major publications. Despite the constant proliferation of their movement and ideas, these groups only occupy a narrow portion of the Los Angeles population. And yet, at least in mainstream environments, they speak for the city.

This experiential dissonance manifests most prominently in the food patterns of Los Angeles. Let’s do a quick test. Whom do national media consider influential among Los Angeles chefs?

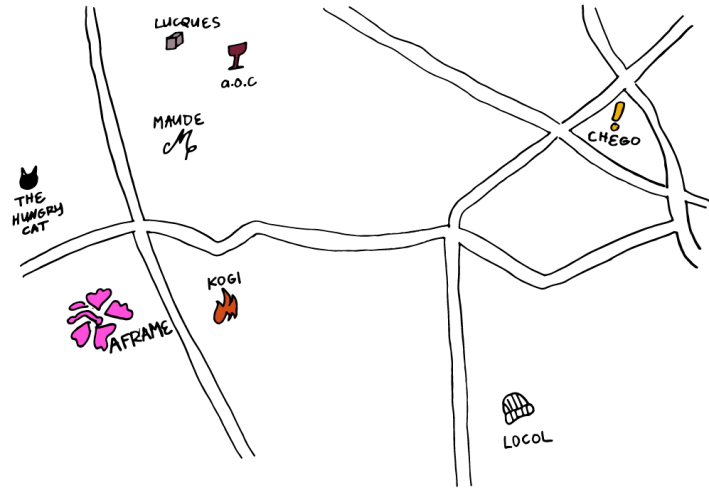

Suzanne Goin, perhaps? The James Beard winning chef who ushered in the small plates phenomenon to Los Angeles cuisine? Or Roy Choi, the inventor of the modern social media-based mobile restaurant, and destroyer of ethnic borders? Or maybe they’re not yet prominent enough. In which case, why not Curtis Stone? The Australian chef has graced many a television cooking show espousing the wisdom of local ingredients, and now he runs a highly acclaimed seasonal restaurant in Beverly Hills. They all seem like reasonable enough responses. Where in Los Angeles do these chefs choose to leave their marks?

With the very notable exceptions of Roy Choi’s Locol and Chego!, these influencers influence on the West side of LA. What else do these chefs have in common? Reformatting old traditions in ways that got attention for their novelty, but are part of longstanding traditions. Small plates have existed forever in most cultures, from tapas to izikaya. Mobile cuisine has also been around for ages, especially within LA, the land of loncheras. Cooking with local produce is a strange thing to call a trend, considering it’s how humans have eaten since the dawn of time. The real trend is having indecipherable ingredient lists.

Goin and Stone's connections to the West side of Los Angeles indicate their connections to the money sources that trickle through the city. Roy Choi and Curtis Stone are repped by CAA, the Death Star agency of high-profile, A List entertainment. All three chefs have appeared on cooking shows, talk shows, or are even producers of movies based loosely on their own lives. They represent a Los Angeles with an eye towards the sky, using locality, sustainability, and LA-specific cultural narratives as a conduit towards globalized fame and recognition. They have literally helped put Los Angeles on the culinary map, and the media cycle perpetuates their aspirations, feeding into their stories as much as these chefs want to tell them.

This isn’t to say their food isn’t great; in fact, it’s downright delicious. In Los Angeles, though, there is a lot of delicious food, so it’s not an objective standard bearer for how power lines develop. The taste itself turns into a corollary of the discussion around culinary esteem. Who represents the other side of the coin?

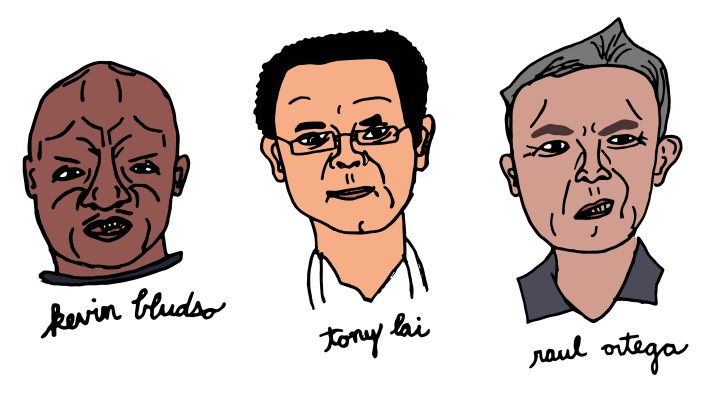

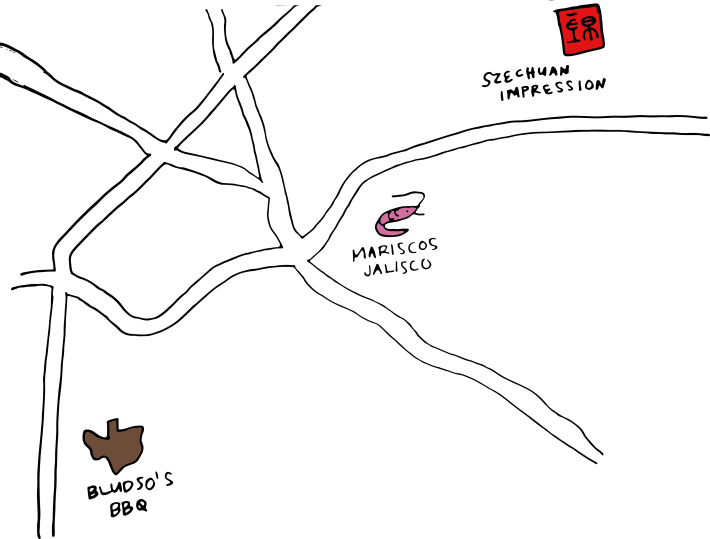

Why does Suzanne Goin win the awards and cookbook deals and philanthropic esteem, and not Kevin Bludso and his esteemed BBQ joint in Compton? Los Angeles loves him so much he opened another outpost on La Brea (a street that, in the mid-2000s, got featured on E! News almost as often as celebrities did). Or what about Raul Ortega of Mariscos Jalisco? His truck is an LA stalwart, he’s collaborated with Jessica Kaslow of Sqirl, and his presence is synonymous with his tacos. Why isn't he a household name? Or perhaps Tony Lai of Szechuan Impression in the San Gabriel Valley. The SGV is the most comprehensive representation of authentic Chinese food in America, but coverage usually lumps the behemoth area into one common experience. And within the expansive coverage of the eastern Valley, and even Szechuan Impression itself, Tony Lai hardly comes up. Even Jonathan Gold, LA’s beacon of local pride and pure love of food, reviewed the restaurant without mentioning Lai’s name.

And where do these restaurants place themselves?

West side, not so much. Of course, most of this has roots in the placement of cultures and ethnicities in general. The population of each environment has a direct influence on the food available in the area, and urban development can't be reduced to the patterns of contemporary culture. What it can do, though, is reflect how much contemporary culture maintains pre-existing paradigms. Without access to the publications, media outlets and money of larger, external-facing organizations, the dichotomy between LA’s local pride and the external vision of the city grows deeper and deeper.

Bludso’s, Mariscos Jalisco, and Szechuan Impression are well-known and respected food destinations in Los Angeles. The places themselves have strong local presences, but it’s often an inward view. And despite their presence on every map or list of LA’s best food destinations, the exposure tends to stop there. This isn’t an inherently bad thing; exposure isn’t obligatory for a positive culinary experience (and, often, it’s a hindrance). But when food publications privilege the easiest stories to tell (see: nationally-recognized faces who create a mutually beneficial relationship between platform and subject), it creates a feedback loop of power.

Representation and action from only certain types of people grants responsibility and innovation on a slim sector of the culinary population. Where’s the agency for the inventors outside the mainstream parameters? If visibility is difficult to attain for these chefs, what hope is there for the truly invisible food workers? The people who spend every hour harvesting, supplying, cooking, cleaning, and supporting the entire industry as a whole. Where’s their book deal?

This essay originally appeared as part of a final project for Karen Tongson's Gender Studies "Maymester" seminar on Food Culture & Food Politics in the Land of Plenty" at USC.