[dropcap size=big]S[/dropcap]he’s tackled race at the Whitney Biennial and dove deep into the last of L.A.’s porn theaters. In tense Boyle Heights, she’s broken news about zoning, and she’s mused on the impact of art critic John Berger, who “set my teenage mind on fire.”

Journalist Carolina Miranda has developed a dedicated and international following for her dispatches on the pulse of the art world in the pages of the Los Angeles Times. Since 2014, she’s been the paper’s must-read arts and culture writer, taking stock of exhibits, controversies, personalities, and the thorniest subjects in contemporary art — from what is arguably its current creative polar center, Los Angeles.

Miranda really became a name back in New York, when around 2007, after the death of her father, she started an arts and culture blog that quickly became a go-to in the heyday of Web 2.0 blogging. It was called C-Monster, and the blog introduced a cutting but always fair and engaging new voice to the formerly stodgy arts writing circuit.

To this day, Miranda is unbelievably prolific. At the L.A. Times, she launched the essential Culture High & Low blog and still edits the paper’s arts and culture newsletter. We met with Carolina recently to talk about her journey, and of course, to sample her favorite taco in L.A. — but we’ll get to that in a minute.

LA TACO: Carolina tell us what you do, and where you’re from?

CAROLINA MIRANDA: I’m a staff writer at the L.A. Times covering art and architecture. … I was actually born in Casper, Wyoming, because my dad had a job assignment, and I came along. But California was always my parents’ base. We were up in the Bay for a bit. My dad worked in heavy construction, so we just went wherever the work was.

As a kid I lived in the Valley. I’m a total Valley girl — well not that part of the Valley. [Laughter] I was in Van Nuys, then we lived in Panorama City, then we lived in Granada Hills, then I went to high school in Irvine, because that totally makes sense.

Wow! A while ago?

Yes in the 80s, because I’m old. I graduated in 1989.

So you had a total ‘L.A. Latina’ upbringing, would you say?

I would say it was a combination. Irvine was very Asian, so I hung out with Koreans, Thai, Vietnamese kids, Chinese. My friends and I would debate about who’s house to eat at depending on what we wanted to eat! So if we felt like South American, we went to my house … if we wanted Thai, we’d go to my friend Arlene’s house.

You’re half Peruvian, half Chilean. Is there a uniquely South American SoCal experience? I’m sure you pass as Mexican to many people, or just Californian, or just brown to people.

People are often confused. They go, ‘You kinda sound Mexican but you don’t really when you speak Spanish.’ Like I have this accent that’s really mixed up. A lot of people ask me if I’m Colombian ...

Is there a typical Southern California-South American background? You know that experience is still pretty new. The big waves of Peruvian immigration really only started coming in the late 80s and 90s, when the situation in Peru really deteriorated. And the migrations of Chileans have always been too small to really register as a community.

There is an element of exile in this migration, right? … [Just then we pass a car playing a slow and steady cumbia from a heavy bass system] As we listen to some … cumbia?

Suena rebajada …

Pero suena rebajada, pero así, argentina o villera, almost.

Yeah, yeah … Who knows. This is L.A. It could be anything!

So, yeah, you had a lot of people fleeing the internal conflict, so there was that phantasmagoric violence that was the government cracking down on leftist guerrillas the Sendero Luminoso and the MIRTA, the Tupac Amaru movement. Combined with a bunch of different things.

And Chile …

And then in Chile, the dictatorship. My mother left before Allende was in power, so she kinda pre-dated that whole thing. But I do have family that left because of it. They were in Mexico for a little while, then they went off to Spain.

And how did you become a journalist?

That’s kind of a crazy question. I was babysitting for a journalist.

Wow.

I did a lot of babysitting in high school, in addition to other jobs to make money. One day this journalist gets home and looks at me and goes, ‘Hey, do you know how to type?’ And my mother, god bless her South American heart; When I was in junior high, she says, ‘You need to take typing because if nothing else works out, at least you’ll know how to type.’

[Laughter] It’s the 80s …

Yeah, exactly. I took a class on a manual typewriter, that’s how I old I am.

Me too, actually …

He was like, ‘Do you know how to type?’, and I go, ‘Why yes I do.’ He goes, 'I’ve just been to Russia, for this story I’m working on, and I need someone to transcribe all my interview tapes' … He paid me eight dollars an hour to do it. So I spent a summer transcribing all kinds of stuff, and it was Robert Scheer. He was a columnist at the L.A. Times at the time.

Classic liberal progressive columnist …

Lefty, like Old Ramparts, one of the founders of Ramparts I think it was? One of those muckity-mucks at Ramparts. Yeah ...

So how did you make a leap to find your own voice?

I always thought I’d be a history professor. … but I think working for Bob taught me that journalism is the most amazing history job you could have, because you’re writing the first draft. So when I went to school, Smith didn’t have a journalism major, but I started working for the school paper. At one point I got a small internship writing for the local daily, the Hampshire Gazette, in Northampton, Mass. One of my first real jobs was to cover church fairs. So I would go to these little working-class towns around Smith and write about their church fairs, you know, boogie rides, and stuffed cabbage.

What a great beat!

It was a lot. After a while they were kind of all the same … [Laughter]

Then you moved back?

I was all set to come to L.A., I was gonna come to UCLA to do a master’s and everything … But I stayed in New York, working and couch-surfing my way through New York, and working at a cafe a night, where I would sling cappuccino, and made cannoli. I can stuff cannoli like nobody’s business.

Then I ended up getting a job as a research assistant at New York News Day. I met my husband there, and then I had a whole sequence of unremarkable media jobs.

RELATED: Support Local Journalism, and Become a Member of L.A. Taco!

When did you find your stride?

I got a job at Time magazine as a reporter, which is a total entry level thing: some reporting, some fact-checking, some writing. And that job taught me a lot. And I worked with people who were amazing writers. That was my J-School, it was Time magazine. I just soaked things up. I was there for a while. And then a wave of buy-outs came ...

Yup.

... And I was interested in writing about culture.

How did you get to L.A. Times then?

I moved back to L.A. in 2012. And then I finally convinced my husband to move back. He’s from Jersey. He was like, 'I don’t know' … And then I brought him out one April when the weather was really shitty in New York and he goes, ‘OK. Let’s do it.’

Yeah!

The L.A. Times was hiring an arts reporter. And I got a call from someone saying, ‘Would you be interested?’ So it was Laurie [Laurie Ochoa, L.A. Times arts and entertainment editor], and she said, ‘Would you be into it?’ And because it was her, and it was clear they just kind of wanted me for me, and I think that was the first time in my life that I’ve had a job like that.

RELATED: My Favorite Taco ~ Patty Rodriguez

The Hills of City Terrace

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap] meet Carolina in City Terrace. To get there from the other side of town, I drive all streets, up from Adams and up to Alameda. Down 7th Street, where I let Soto guide me over through the bustling little Boyle Heights strip that is Wabash. Right into the point where the street begins to transform with the curves of a hilly country road, where it is reborn as City Terrace Drive.

I’ve been here before — Willie Herron Jr. once walked me to the City Terrace alley where his most renown art piece is located, “The Wall That Cracked Open” — but not a lot. The hills rise sharply against the sky, and I can only imagine the views the original Tongva people had from these peaks, over the snaking river to the west, before the water belonged to Nuestra Señora.

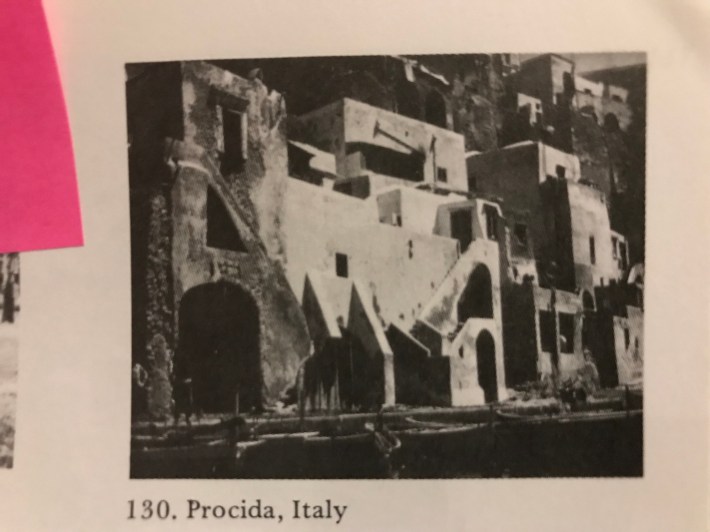

I can also tell I am nearing City Terrace because the traditional Victorian quality of the Boyle Heights homes give way to houses that seem to fit snugly together, each structure perfectly in communion with those around it, like a quilt. Miranda later tells me an artist once remarked that the style of the houses on the hills of City Terrace resemble those of coastal Italy, so she looked it up. I ask her about this in an email later, and she responds with this note and image:

“It's Procida, Italy — which is off the coast of Naples. I've never been, but I first saw a photo of a home in Procida in Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's 'Learning From Las Vegas,' and something about the staircases that creep up the sides of buildings seemed to echo some of the designs I see in City Terrace.”

How long will City Terrace stay as it is? Will these same longtime families stick around for generations more? Carolina has dealt with the questions surrounding art and displacement in her reporting, too. She’s actively covered the efforts of anti-gentrification activists to push out private art galleries from nearby Boyle Heights. We turn to this subject.

L.A. is facing a lot of questions with artwashing. Are these galleries guilty of that, or what are ways that can these issues be mediated in a city like where issues like housing and displacement are kind of bigger forces that the art world can’t control?

It’s super complicated, and art has its very controversial relationship with capital, when you think about museums, and what they represent, and that it’s a place where patrons that maybe made their money in not-so-hot ways can go position themselves as great cultural leaders.

Money and development do use art for its interests, as a tool of attraction, as a tool of like the Richard Florida thing, making cities attractive with the “creative class.” But what’s happened a little bit with the debate is sometimes it gets flattened, and all galleries become a tool of real estate, all artists are tools of that system.

The art-world is the world.

And the fact is the art-world is the world — there are super international galleries that swoop in and are well-funded, and there are artist spaces run by some guy, and they operate month-to-month. And they don’t have the same interests, or values.

For me, I love art, I love writing about art, and artists have really interesting things to say, but yes, they function within this system of capitalism, which is this ugly system that displaces people, that victimizes them, exploits them. While I love art and some of the beautiful things it can express, I’m also frustrated by it and the institutional aspects that manifest.

As someone who’s grown up in all kinds of communities, and has been pushed out of some them, there’s this real frustration that cities operate in this way where rampant speculation and rampant development are just the rule of the day.

Right.

There are no protections. And so it’s this issue that I struggle with, and I wish I had the short and easy declarative answer. Gentrification is this confluence, it’s this perfect storm of things, it’s economy, it’s regional, it’s the feds coming in and doing crazy things.

Like, a neighborhood never gets gentrified just for one reason. I feel sometimes the narrative is flattened down: artists move into a neighborhood, and then the neighborhood gets gentrified … so I think in the coverage I’ve tried to do, is just trying to take a step back, and think OK, it’s this really complicated soup of things. Let’s look at what those things are.

Look at Boyle Heights ...

Its proximity to the Arts District, its proximity to downtown, is just making it too appealing to a bunch of real-estate speculators, whether they’re connected to the gallery system or not. Whether all of those galleries leave, there are going to be forces that shape Boyle Heights, because we have zoning laws that are weak, because elected officials don’t always represent the people they are elected to represent, because we have a city where development is allowed sometimes without low-incoming housing written in … money rules the day.

It’s easy to have the quick take on it, but what are the important factors? And in that confluence, what are the most important things to think about?

To switch gears a little bit, you’re part of the bargaining unit at the L.A. Times Guild. How is that, and what can readers expect about their paper now that it’s been bruised and beaten for so many years?

Well, you know, don’t call it a comeback. Or call it a comeback, to get all LL Cool J on you [Laughter].

It’s been a crazy f--king year. We unionized. We were sold to new local ownership. Now we’re bargaining with the new owner. I’m hopeful, you know. I think the L.A. Times has been bruised and battered, and they know it … We’ve seen a willingness to negotiate. I think they’ve recognized we haven’t been well treated. What action that’s going to translate into down the line? I don’t know.

Well good luck. Now tell us what your favorite taco is!

My favorite taco is the taco de mole at Quesadilla Gonzalez.

We just had it. It was amazing. Tell us about this place.

It’s a little taco truck that parks on City Terrace Drive, right as you take the exit of the 10. It parks right there under one of the Muffler Men.

They’re there in the evenings around 530-ish, it’s the Gonzalez family, Don Pascual and his family. They’re from Puebla. And they do tacos de guisado. They have cecina, and chicharron. It’s nice and crisp.

I really like them because they’re an amazing family, they work together, they produce this amazing food … You know, in this age in which food has become this thing that’s Instagrammed, and hyped, they’re really about nourishing, and feeding people, and there’s something about that, that I find really great. That’s really what food is about, and that’s what they do.

And the tortilla is made by hand.

Always key…!

RELATED: Every Entry of 'My Favorite Taco'