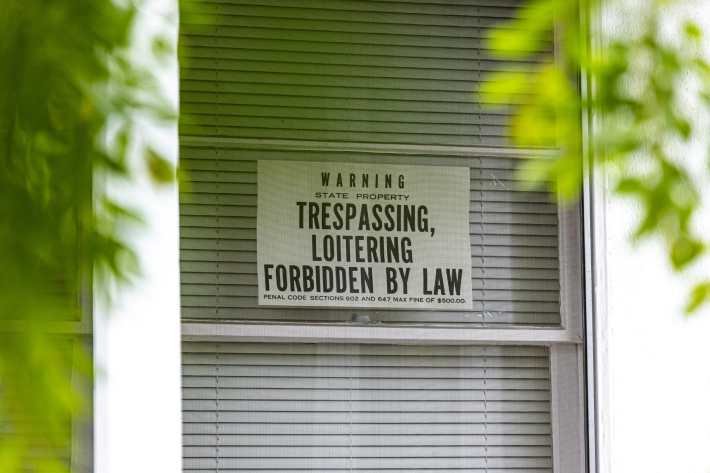

"If you come in here, you risk getting arrested,” Ruby Gordillo said before unlocking the front door of 3135 Sheffield Avenue.

From the dining room window of the two-bedroom one-bathroom house in El Sereno, Gordillo’s new roommate Martha Escudero, a housing insecure mother with three young kids, peered through the blinds intently, keeping an eye on the street, while Ruby and Martha’s children planted succulents in the front yard and played in the hand-trimmed grass. Across the street, five armed California Highway Patrol officers watched over nearly one hundred supporters.

We’re working in real time to secure hotels, motels, and trailers to house our homeless safely and protect our communities and the spread of #COVIDー19.

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) March 15, 2020

While the city prepared to shut down its schools, libraries, restaurants, and bars, Ruby, Martha, and Bonito, “reclaimed” a vacant house in the 710 corridor of El Sereno. The property, along with over 100 other vacant houses divided between four different cities, is owned by Caltrans, one of the largest landowners in the state of California. Aside from seeking shelter from the recent rain, the action was inspired by unhoused mothers in Oakland and Gavin Newsom’s concerns over the COVID-19 virus.

The months-long standoff in Oakland between two unhoused mothers and a development company based in Redondo Beach resulted in a militarized police eviction that attracted over 25 sheriff's deputies and left the mothers in handcuffs, but ultimately ended in victory after Wedgewood Properties made a “good faith agreement” to sell the property to Oakland’s Community Land Trust.

“We are urging for vacant houses to be homes for these unhoused folks– now,” Gordillo said during a press conference outside her reclaimed home on Saturday.

They call themselves reclaimers because in their eyes the property is already theirs. According to the reclaimers, the once privately held land was acquired by Caltrans with taxpayer’s money and with the intent to use it for “public good” (ie: a public freeway).

During the 1960s and 70s, Caltrans began buying up hundreds of privately owned properties in El Sereno, Alhambra, Pasadena, and South Pasadena through Eminent Domain—a controversial constitutional law that gives cities and states the legal authority to seize private land for public use—in anticipation of a freeway that would connect the 210 and 710 freeways.

But after decades of resistance from community members and local cities, Caltrans eventually abandoned plans to build a surface freeway and began working on a proposal to create an underground tunnel instead. But last year, Governor Newsom signed a bill that effectively put an end to the idea of the 710 freeway extension.

After decades of lawsuits and fighting, longtime corridor tenants were finally presented with an opportunity to purchase homes that many of them had rented for decades when Caltrans agreed to eventually sell off the properties.

But years later, only a handful of properties out of several hundred have been sold and in some cases, long-term tenants have passed away, been priced out, or evicted before they had a chance to buy their homes. Once houses are emptied, they typically remain vacant. Today there are an estimated 163 unoccupied homes within a few square miles.

Hugo Garcia, the founder and Chairman of El Sereno Organizing Committee and longtime resident of the corridor told L.A. Taco that 20 years ago a woman that lived across the street from him passed away and the property is “still vacant.”

Garcia has been organizing against the 710 freeway extension for decades. “What Caltrans has engaged in throughout the years is mismanagement as a property owner.” Garcia pointed to a 2019 audit that found that Caltrans had mismanaged millions of dollars in funding. “When they empty out a home for whatever reason, they don’t fix it, they don’t rehab it, they leave it there.”

Historically, communities of color have been disproportionately impacted by eminent domain laws and specifically freeways. Neighboring Boyle Heights, a community that is over 95 percent Latino, has four freeways running through it. Garcia notes that most of the homes that Caltrans owns along the 710 corridor are in El Sereno, a community that’s over 80 percent Latino, “We always get dumped on.”

Before Ruby, Martha, and Benito called 3135 Sheffield home, the house belonged to Jaime Sierra’s mother. Sierra’s mother lived there for 35 years until his father passed away and his mom couldn’t afford to pay the rent, which had recently increased from $700 per month to over $1,500.

Sierra’s mom tried to petition the rent increase telling Caltrans she couldn’t afford the new rate and filing paperwork to appeal, but “They kept saying they didn’t receive the paperwork,” Sierra said, “but they did.” On February 28th of this year Sierra’s mom was evicted.

Despite the fact that the home was inhabited just a few weeks ago, there is no running water or power at the house but the reclaimers are trying to solicit a refrigerator and have already picked up a generator. Eventually they hope that the utilities will be turned back on.

According to Pasadena Star-News, it’s common for Caltrans to deny receiving paperwork or refuse to accept rent from tenants when they’re involved in litigation proceedings with them.

Tina Moreno, a 17-year Sheffield Avenue resident, is currently in the middle of her own battle with Caltrans.

Two years ago she was evicted from a home on Sheffield Avenue that she lived in for over 15 years after a break up. Like Sierra, her rent increased from a few hundred dollars to over $1,000 per month overnight. Moreno says that the house eventually became uninhabitable after being neglected by Caltrans for decades.

After handing over thousands of dollars to avoid eviction, Caltrans evicted Moreno anyway. For two years, Moreno, a mother of two, lived on the streets before Caltrans finally agreed to relocate her into another house down the street.

The night before the reclaimers took over 3135 Sheffield, 5 LAPD cars showed up outside of Moreno’s new house. According to Moreno, she was accused of breaking and entering and asked to vacate the property. “We already had put my furniture in,” Moreno said that her sister had recently helped her move in and that she had been living in the house for over two weeks before she was accused of trespassing, “I had already gotten my mail.”

Moren showed the police her paperwork and explained, ‘I was one of the ones that got relocated.” While she wasn’t arrested, she said the experience left her humiliated. “I said, ‘You put me through hell and back and you guys are going to put me through this again?’ No Caltrans people even came.” That same night, Moreno ended up meeting the reclaimers purely by chance.

Many other corridor residents have similar stories of being forced to live in homes that are nearly uninhabitable, receiving significant rent increases, Caltrans refusing to accept rent or denying that they received paperwork and elderly tenants being forced out of their homes or pushed to their graves. “A woman down the street was dead for two days before they found her,” Moreno told L.A. Taco.

But for Ruby, Martha, and Benito, the corridor represents opportunity.

“I just want my kids to have the same opportunities that I had,” an exhausted Gordillo told L.A. Taco during a brief moment of solitude Saturday afternoon. The lifelong resident of the San Gabriel Valley and East Los Angeles said she chose to move in with her brother when she was just 10 years old to be able to stay in her beloved community. “I had a yard, I was able to go outside and play with friends. We can’t do that in our neighborhood.”

Before moving into the Sheffield Avenue house, Gordillo and her children were confined to one small room in Westlake. “I have children that are gifted and are having a difficult time excelling academically. We’re constantly hearing each other’s breathing. That’s not what a child should be living in.” On Saturday Gordillo’s kids got to play in their new front yard for the first time.

“We’re going to occupy this house and make it a home,” Ruby said.

Originally the reclaimers were going to move into three separate houses but early Saturday morning, two members of the coalition that were described by organizers as the people that helped the reclaimers gain entry into the vacant house were arrested. They were later released on their own recognizance after significant community support.

After the press conference on Saturday, organizers emptied a U-Haul containing second-hand furniture, while the kids ran around the yard and bowls of vegan rice, beans, and stew made it into the hands of supporters.

The event turned into a celebration when a trio of three musicians serenaded a dwindling but supportive group of protestors. “Y las casas nos las tienen que dar porque es injusto que las gente viva en la calle en esta ciudad,” the group sang their own variation of Luis Manuel’s classic ballad, “Sabor a Mí,” a love song about a poor man trying to appeal to a lover.

On Saturday evening, the three reclaimers and their five children slept under the roof of their new home without interruptions, although CHP officers were observed by L.A. Taco shining spotlights into other vacant homes at approximately 11 PM.

A spokesperson with the LAPD media division said they weren’t aware of the situation in El Sereno and told L.A. Taco to file a public records request. The East Los Angeles division of the California Highway Patrol, the division of the CHP that oversees parts of El Sereno including 3135 Sheffield Avenue, could not immediately say how they would respond to civilians occupying state property and added that CHP is a state agency not bound by one local jurisdiction.

At a vigil held on Sunday that brought together neighbors and various religious leaders, Ruby, Martha and Benito thanked supporters for standing by them over the last two days. “What has been said here tonight is very true, this land has been stolen by using weapons as a force,” Benito echoed the sentiments of religious leaders. The 70-year old has been living in a van since 2005 because his minimum wage job didn’t provide enough income for him to rent an apartment.

Pastor Smart concluded the service by honoring the courageous mothers, Ruby and Martha saying, “As our sisters did in Oakland, our sisters have started in Los Angeles. After the revolution, when the movement starts, we’re going to say, it began with you.”