[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap]t 65 years old, author Luis Rodriguez is caught in a surreal moment.

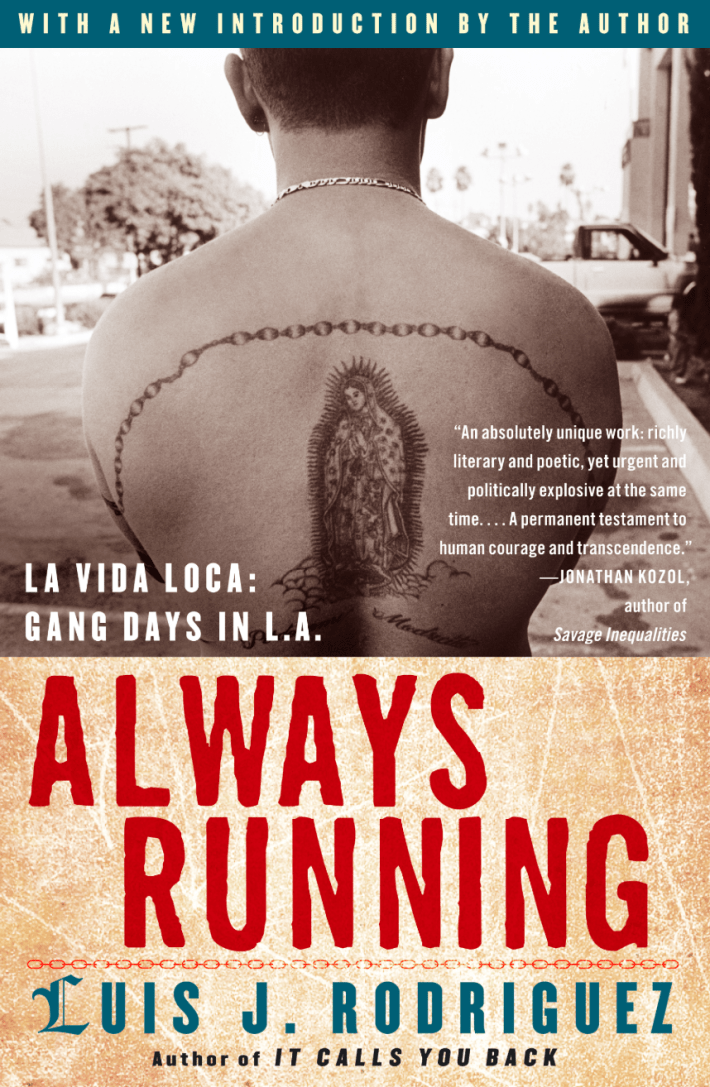

A stage adaptation of his 1993 memoir Always Running about his life as a pre-teen gang member in East L.A. is set to premiere at the end of the month at Casa 0101 in Boyle Heights.

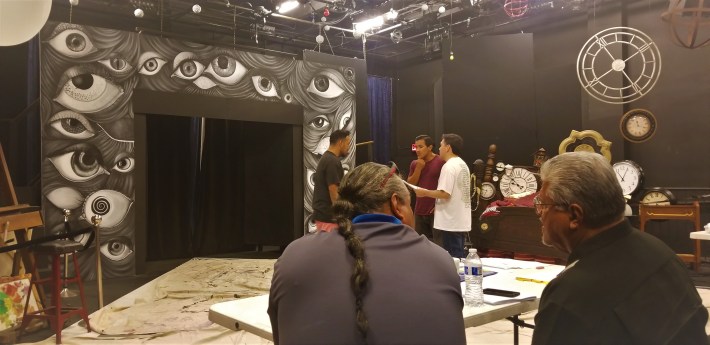

He’s giving notes to the director, the two actors on stage, including one who’s portraying a younger version of himself. The stage is set for a separate play on Salvador Dali. Melted clock faces and floating eyeballs frame the stage.

The scene before Rodriguez is from his own life, but with that one degree of separation that comes from being an adaptation of a memoir on his life brought to the stage, so he’s hearing his words performed back to him years later. It’s an ouroboros of a moment.

Beyond My Control

For decades, Rodriguez has spoken at jails, work camps and prisons across the country to incarcerated men and boys, he’s spoken to students at schools and universities all about the power of healing. It’s a concept that Rodriguez is intimately familiar with, a way of life he says he embraced after he spent his youth getting beaten up or beating up rival gang members, getting shot at and OD’ing on heroin. Three times.

Incarcerated young men who read his book find comfort knowing there is someone who survived that life, went on to become a writer and went to college.

But the picture in their minds from the character in the novel does not always match up to the soft-spoken, bookish Rodriguez when he appears for his speaking engagements.

“I go into institutions and people expect this heavy, hardcore guy—all scarred up,” says Rodriguez. “I look like a regular schmo. I look like their dad or their tio.” (One of the few remnants that Rodriguez was a cholo is a small Pachuco cross tattoo on his hand—three dots over a cross, meaning Mi Vida Loca, which is the subtitle of his memoir.)

“I have that survival syndrome. But now I have to turn it around. Alright, then let’s do some good.”

Rodriguez also speaks about the boys who became men who became heroin addicts and then empty apparitions of their former selves. Or he speaks about the combination of drugs, violence, and anger at the world over systemic inequities put into motion long before any of these men were born, the invisible hand that held them down.

Obviously, Rodriguez says, he should be dead.

“It comes out in this story where someone says, man you must have a guardian angel. I don’t know why I survived most of this stuff I went through. Good friends of mine shot at once, and dead. I got shot at half a dozen times and never got hit. I was so fortunate that I have to say it’s beyond my control,” says Rodriguez.

“I don’t want to judge all these people that were my friends. They’re worse than me? I did a lot of crazy things that I didn’t pay for, like they did. I have that survival syndrome. But now I have to turn it around. Alright, then let’s do some good.”

The advocacy work has kept him busy, helped him heal but the impulse that he grew up with still lingers. Sometimes when he’s giving a speech at a jail or work camp and a fight breaks out he says he can’t help but get right into the mix, like a reflex.

Psychologists at these institutions have casually mentioned to him that urge is a symptom of someone with post-traumatic stress disorder because when other people want to flee he wants to fight.

Barrio Warfare

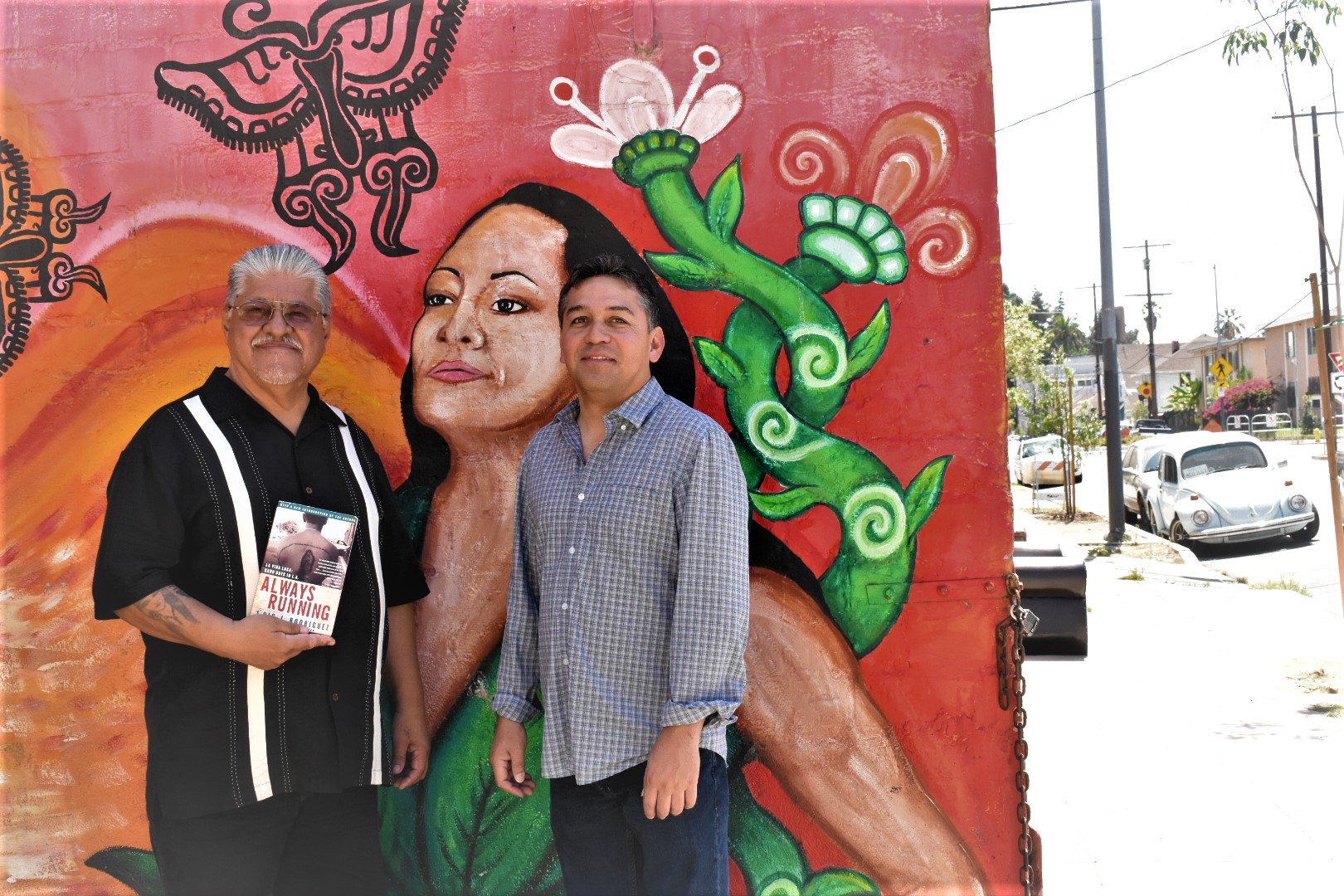

Director Hector Rodriguez—no relation—says the adaptation of Always Running is about the healing of the character “Luis” after all the hardships he’s experienced. Sitting next to Luis Rodriguez, Hector is wearing a Lalapalooza t-shirt as he gives direction to “Luis” played by Rufino Romero.

The actors on stage are going over a scene between a former rival gang member and “Luis.” Nerry Cividanis plays the other role and both men listen to Hector Rodriguez discuss how the scene should be approached technically. Luis Rodriguez explains the scene is charged with confrontation, but also tinged with pity and forgiveness.

They wanted to avoid the convenient, tatted up 'vato' who plays heel and provides comedic relief as he happens to deliver an 'Órale' with comedic timing.

Cividanis is supposed to be held at arm’s length by Romero. When it seems like the scene will devolve into violence it ends with an embrace. There’s a resolution but it leaves neither man particularly excited. In a way, it’s cathartic because there are no easy answers for these men.

Of course, the undying cholo caricature loomed large in Luis Rodriguez and Hector Rodriguez’ minds when it came to the dialog and expressions of the play set in the 1960s and 1970s. They wanted to avoid the convenient, tatted up vato who plays heel and provides comedic relief as he happens to deliver an Órale with comedic timing.

Hector Rodriguez explains that the characters need to appear vulnerable while also somewhat conflicted.

He says, “The circumstances they were forced to live in shape them. This is to show them as real as possible.”

This play will not include his family’s early years when they moved from El Paso to being homeless and then to South L.A. It won’t mention that as a child he was separated from the rest of his classmates for speaking Spanish and because he was too shy to ask to go to the bathroom, he would wet his pants.

This version will not mention that his partner, Trinidad Rodriguez, or their co-founded Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore in the San Fernando Valley. Nor will this play mention that Luis Rodriguez reconciled with his son, Ramiro, while he was in prison for 13 years for attempted murder and he wrote to his son in prison that he would not give up on him. This play will not even touch on the time he ran for governor of California on the Green Party ticket and secured 1.5 percent of the vote.

That play would be an odyssey.

Instead, the play will explore how he joined the Lomas gang at 11-years-old when his family moved to the San Gabriel Valley. That’s when he says the violence ratcheted up, what he calls “barrio warfare,” the type of upbringing that funneled anger into young men and estranged him from his family for years. He jumped other kids, stabbed, stole, and shot at others.

This was toxic masculinity before there was a term for it, especially in the barrios of Los Angeles.

Drive-by shootings in his book happen so fast that in one sentence, friends are speaking and then are on the ground, killed in retaliation for someone else left for dead in another shooting or stabbing.

This was toxic masculinity before there was a term for it, especially in the barrios of Los Angeles.

In an updated forward to his memoir, Luis Rodriguez says he might have abandoned the gang life when he entered his 20s, but he practically abandoned his son, Ramiro, and daughter, Andrea, when he divorced their mother.

Since then, he’s reconciled with his family.

All the mistakes Luis Rodriguez says he made as a father were chronicled in his 2011 book “It Calls You Back.” On stage, the “Luis” performing the scene mentions he has a baby, but offstage father and son sit next to each other.

“They cut me out of the play. That’s OK, I’m the baby they’re talking about,” said Ramiro Rodriguez, now 45-years-old. “It’s not always easy having an author-father talk about all the family stories. A lot of the family was upset, mad. You get used to it.”

Gentes in the Barrio

L.A.-based poet Iris De Anda calls Luis Rodriguez a maestro.

“He put in the work for some generations before I came along. I feel like he opened the door for a lot of us Chicano artists,” says De Anda. “Especially the work he’s done for the community and the way he happens to connect people.”

“To me, you can’t demonize cholos. You can’t glorify them either, but their humanity is much more complex. They’re not the greatest, they’re also not heroic. They could be, but we can’t romanticize them,” says Luis Rodriguez.

She will join Rodriguez and a group of poets in a trip to Cuba later this year, where they will perform at the Casa de las Américas. It’s a far cry from the boy who didn’t think he would be able to ever leave his barrio.

This upcoming stage adaptation is about the man that he would eventually become.

Casa 0101 plans to invite kids and adults from work camps and Homeboy Industries to see the performance, to give another generation a chance to hear Rodriguez’s message.

Because the anger and frustration that swelled up in him did not simply burn off but was channeled into his work. He can’t stay mad at himself or the barrio or even the others who continued down that path.

“To me, you can’t demonize cholos. You can’t glorify them either, but their humanity is much more complex. They’re not the greatest, they’re also not heroic. They could be, but we can’t romanticize them,” says Luis Rodriguez.

He adds, “Most gentes in the barrio are not cholos. We’re dealing with a relatively small subculture. I watch a lot of media and I just can’t think of one that does it right. Gets the cholo accurately. Because you don’t see them reading poetry, helping others. Those things happen all the time.”