[dropcap size=big]F[/dropcap]or Edgar Baca, it all started with a cooler full of his homemade Sinaloan-style enchiladas at Nobu Malibu.

“Los trabajadores también tienen que comer (the cooks also have to eat),” he tells me in his distinctive Sinaloan accent, now made famous in Narcos Mexico. “I started from my home kitchen, taking orders for traditional Mexican dishes that the rest of my coworkers at Nobu craved: chiles rellenos, ceviches, taquitos, and more. Then, those orders started being for people like Pepe Aguilar, Marco Antonio Solis, and Carlos Vela. Now I have this restaurant.”

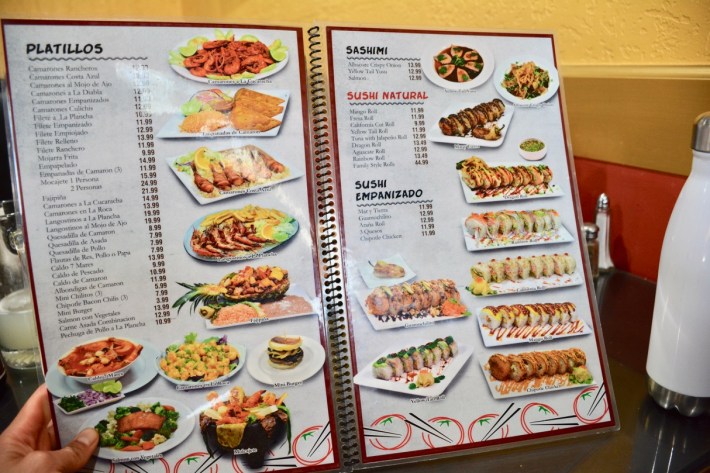

Mariscos y Sushi Los Tomateros looks like any other Mexican sushi restaurant in southeast Los Angeles; though one hidden in a side street near Tweedy Boulevard. Its logo hints of Baca's past: a tomato, the prideful state crop of Sinaloa, some chopsticks, and the name of Baca’s hometown's famous baseball team in the Pacific Mexican League—Los Tomateros de Culiacán. The menu has the Sinaloan mariscos and sushi classics, boasting things like aguachile and empanadas de camarón on one side of the menu, and Mexican sushi classics like Mar y Tierra (surf and turf) rolls loaded with cream cheese and other crispy things.

Nonetheless, there are a couple of dishes that hint of the fascinating story behind this unassuming Mexican seafood restaurant: “Yellowtail Yusu” and “Camaronés en la Roca,” the paisa-fied names of two namesake dishes that pioneering sushi chef and founder of the Nobu empire Matsuhisa has credited as “making his career.” That’s because Baca’s has been the busboy for Nobu's Malibu location for nearly the last 15 years, and like many other sushi chefs around the country, he has taken inspiration from his boss for his Mexican sushi menu. Albeit, approximately 34 miles away from Nobu for his fellow working-class Latino neighbors in Lynwood, and for less than half the price.

“I’ve been working two shifts every weekday for the last 14 years. I get back home from my shifts at Nobu at 2 AM, wake up at 9 AM the following day to open Los Tomateros, and spend sometimes four hours in traffic each day,” Baca tells me very matter of factly. “I don’t have any investors or many other resources for my restaurant; it’s all been my money after saving up. It’s been a big sacrifice, but here we are still.”

Baca’s story is inspiring, but more importantly, his sazón is outstanding. For starters, the rice in his Mexican sushi is perfectly chewy and not the soggy mess that is the norm at other Mexican sushi restaurants. He uses the same rice variety as Nobu and the same technique to cook it. The slices of sashimi on his plate are pristine. His empanadas de camarón are flaky and tender in the kind of style you would find along Mexico's Pacific coast.

‘I owe it all to my drive of always rising above the rest and coming up as an immigrant, God willing.’

Like any other great sushi chef at a counter, Baca is also willing to make you something off the menu using the fresh fish of the day. On the Sunday afternoon that I was there, when I ask if he has callo de hacha (scallop, which is a status food for many Sinaloans) on the menu, he runs to the kitchen to grab a Ziploc full of bulging fat bivalves. He informs me that proudly sources it from Mexico. He instructs me to poke the bag so that I can see the scallops are firm and therefore fresh, instead of squishy and most likely previously frozen.

When I approve, he leaves to the kitchen and returns. The omakase-style surprise dish ended up being a raw scallop dish that was somewhere between an aguachile and a tiradito. He follows the same Peruvian approach to raw seafood—using copious amounts of chiles and acid—that made Nobu famous in the first place but using chiltepin chiles from Sinaloa instead of aji chiles from Peru.

“I owe it all to my drive of always rising above the rest and coming up as an immigrant, God willing,” Baca finishes. “We have a saying in Spanish, “El que no sueña, despierta. (If you don’t dream, you wake up.) This whole industry is fueled by the hustle and dreams of people like myself. It’s not something that happens overnight, so we gotta keep at it. It’s the only way a lot of us know how to function.”

Baca is filled with philosophical lessons about the value of hard work. He is the embodiment of every single first-generation Latino immigrant who makes up the majority of the back-of-house labor in kitchens across the United States. Not to mention, he holds the ideal loyalty that most restaurants hope to develop with their employees, happily working for nearly 15 years in the same position. He honed his chops for years in hopes of opening up his own little spot one day, and he did. The dream came true for Baca, but he is the first to acknowledge that it hasn’t come easy and that making your dream come true just means that you have to work twice as hard to keep that dream a reality.

‘You always get over the hump if you try, you may be crying and you may be drowning, but you will get over it—it’s a process.’

“I’ve had the electricity cut from my restaurant two to three times and there were times I didn’t even have the money to buy a single bunch of cilantro or a cucumber. On those days, you have to put your pride aside and do what you need to do to get over the hump,” Baca admits. I thank my wife and our extended family who have loaned us money in the past. You always get over the hump if you try, you may be crying and you may be drowning, but you will get over it—it’s a process.”

What’s helped Baca balance the expenses of running an independent small restaurant business in Los Angeles on his own is the word-of-mouth among some high-profile customers who come to him when they are in Los Angeles and crave the unabashed flavors of the Mexican coast. He’s catered every kind of party for notable Mexican actors, actresses, corrido singers, and soccer players who play for Mexico’s national team. Some, like Carlos Vela and others, whom he met while bussing their tables at Nobu. He takes a lot of pride that many of them return to Los Tomateros and refer his food to their friends.

Just like Matsuhisa changed the American sushi game by using aji chiles, Baca is helping to prove that Mexican sushi is not just a novelty act, by using the same quality sashimi and rice as his pioneering predecessor but with the assertive flavors and sensibilities that only a Sinaloan knows how to pull off.