[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]n the wake of the protests sparked by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, monuments to White supremacy have been falling across the country. This moment builds off the recent efforts following the racist killing of nine black churchgoers at the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston and the White supremacist violence in Charlottesville, as well as generations of unheeded protests and advocacy amongst Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.

Plaques, statues, and busts—from Alabama to downtown Los Angeles, and even outside the United States in Bristol and Brussels—have been removed, sometimes by acts of government, but quite often by groups of citizens taking the question of historical memory quite literally into their own hands. Popular Mechanics even published the handy article, “How to Topple a Statue Using Science - Bring that sucker down without anyone getting hurt.”

Here in Los Angeles, where a plaque erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy commemorating the dozens of Confederate soldiers buried in Hollywood Forever Cemetery was removed in 2017, the University of Southern California has recently removed the name of its fifth president, noted eugenicist Rufus B. von KleinSmid, from its Center for International and Public Affairs. On June 20, in Father Serra Park next to El Pueblo, the historic birthplace of the city, Indigenous activists tore down a statue of Junipero Serra. Otherwise, public attention has largely focused on the well-documented history of brutality of the LAPD and the Sheriff’s Department—further accentuated by the murder of 18-year old Andres Guardado in Gardena—District Attorney Jackie Lacey’s handling of police misconduct cases as she faces a stiffening re-election, and the fast-changing political dynamics around re-envisioning community safety.

His epitaph reads - “He Was A Man.”

Los Angeles, however, still has a fair number of ex-Confederates in its midst. The Glendale neighborhood of Rossmoyne takes its name from the estate of the Confederate soldier and eventual federal judge Erskine Mayo Ross, who is also the namesake of the city’s Ross Street. Hilgard Avenue, which forms the eastern boundary of the UCLA campus in Westwood, is named for Eugene Hilgard, the UC Berkeley geologist, and chemist who served in the Confederate Nitre Bureau, assisting in the South’s war-making capacity. Hilgard’s colleague in both the Nitre Bureau and at Berkeley was Joseph Le Conte, the slave-owning White supremacist co-founder of the Sierra Club, whose name adorns the LAUSD middle school in East Hollywood. And then there is Captain Cameron Erskine Thom, safely ensconced in the 26th-floor mayoral portrait gallery in City Hall, whose monuments are not so easily torn down.

Confederacy in a Boyle Heights Cemetery

There are few places that still reveal the varied and discordant strata of the region’s history better than Evergreen Cemetery, the oldest private, non-religious burial ground in Los Angeles. Since its opening in 1877, the once-fashionable cemetery has become the final resting place for an array of characters from the city’s past, stretching from real estate barons to carnival workers in the “Pacific Coast Showmen's Association.” Evergreen, while open to most Angelenos of color, was initially racially segregated, and distinct ethnic and racial enclaves remain to this day.

A still-active cemetery that sees families tailgating next to gravestones or neighbors utilizing the track along its perimeter, Evergreen has for many years been severely neglected, a victim of water rationing from the state’s recent drought as well as revocation of its operating license and legal action stemming from circumspect burial practices.

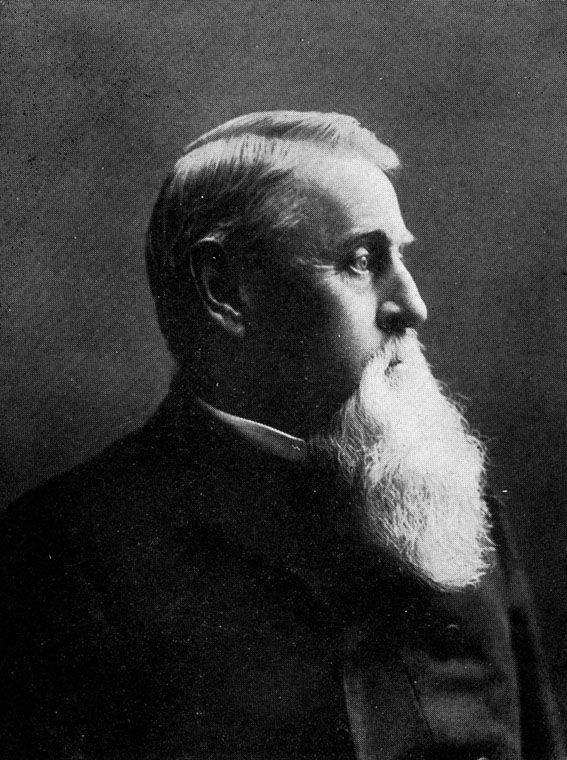

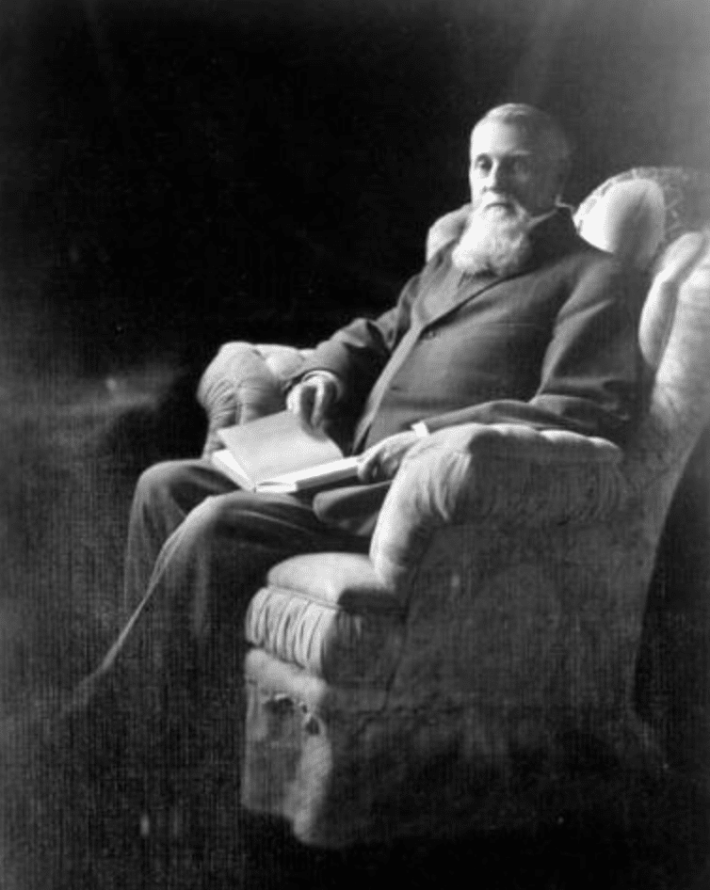

Near the entrance of the cemetery stands the weathered, but still imposing obelisk that marks the grave of Cameron Erksine Thom. His epitaph reads—“He Was A Man.” Indeed, Thom’s life stretched the arc of 19th-century America. Born in Culpepper, Virginia in 1825, Thom, whose father was an officer in the War of 1812 and was a longtime Virginia state senator, studied law at the University of Virginia before heading west for California in search of gold, arriving at Sutter’s Fort in late 1849. After a brief and stint as a prospector, Thom relocated to Sacramento, where he opened a law practice.

In his later career, Thom served two additional stints as Los Angeles District Attorney—in which he was the lead prosecutor of the racist lynch mob that brutally murdered at least 17 Chinese immigrants in the 1871 Chinatown Massacre...

An appointment as a deputy agent for the U.S. Land Commission brought Thom to the small town of Los Angeles in 1854 to help resolve property disputes stemming from the end of the Mexican War. In short order, Thom was appointed both City Attorney and District Attorney for Los Angeles, and in 1857 he was elected to the California State Senate to represent a district that covered the near entirety of Southern California, a position Thom held for two years, covering the 9th and 10th legislative sessions.

In his later career, Thom served two additional stints as Los Angeles District Attorney—in which he was the lead prosecutor of the racist lynch mob that brutally murdered at least 17 Chinese immigrants in the 1871 Chinatown Massacre—and he was elected the 16th Mayor of Los Angeles, a position he held for two years, from December 1882 to December 1884. Having invested heavily in real estate, Thom co-founded the city of Glendale and was at one point the city’s single largest taxpayer.

Thom also served as an incorporator and board member of the Farmers and Merchant Bank, a charter member of the Southern California Historical Society, a member of the 1888 City of Los Angeles Board of Freeholders that rewrote the city’s charter, a founding member of the California chapter of the Society of Colonial Wars, and a member of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, among his many civic and professional activities.

Noting his death at the age of 89 on February 2, 1915, the Los Angeles Herald remarked that Thom was one “of the most prominent, best-loved and oldest pioneers of Los Angeles” and that he “took a conspicuous part in the upbuilding of Southern California.” The Los Angeles Times was equally laudatory, noting that “the company of several hundred persons who assembled to do honor to his memory was the most notable gathering of leading men of the old school scene at any similar service in the city in recent years.” In the midst of describing his West Adams home as “evidence everywhere of refinement, culture, and wealth,” The Times makes a brief, passing reference to another element of the life of “Capt.” Thom—his service to the Confederacy.

The life of Cameron Thom and his family embodied the early history of Los Angeles, and the corresponding development of the United States, through their efforts to uphold and expand White supremacy. From birth, Thom was surrounded by and benefited from the institution of chattel slavery. Berry Hill, the Thom family’s 600-acre plantation, was run by 200 enslaved persons. As noted in My Dear Brother: A Confederate Chronicle, a collection of the family’s correspondence, “The Negroes were singled out for their abilities: taught carpentry, iron-work, shoemaking…and of course, the various skills required in the growing of tobacco, for long months of cultivation by many careful hands were needed to bring the money crop from seedbed to curing barn, to hogshead, and finally to market.” On his Gold Rush journey to California, Cameron and his compatriots had enslaved persons with them—per his family’s correspondence, “They proposed to buy eight conestoga wagons, to equip them with all necessary supplies, and to man each with its own Negro wagoner and cook.”

Thom was also supportive of the 1859 effort to divide California into two states, an undertaking supported by Southern politicians hoping to extend slavery to the Pacific.

Moving west did not diminish Thom’s connection slavery—in fact, Thom used his tenure in the State Senate to try to undermine California’s status as a free state. In 1859, Thom proposed legislation to rework the state’s forcible apprenticeship laws to allow for the importation of enslaved Black youths into California. Chronicling the machinations in “Freedoms Frontier: California and the Struggle Over Unfree Labor, Emancipation, and Reconstruction,” Professor Stacey Smith quotes from The Sacramento Daily Union that the intent of Thom’s bill was “negroes under the age of 21 years, the property of Southern gentlemen emigrating to the state, may be admitted and held in bondage until they have reached a majority.” Thom was also supportive of the 1859 effort to divide California into two states, an undertaking supported by Southern politicians hoping to extend slavery to the Pacific.

In March 1863, Thom, one of the most notable political figures in early Los Angeles, would leave his recently motherless child—named Albert after the Confederate general Albert Sidney Johnson and who would die before his father’s return to Los Angeles—and his adopted home to take up arms in support of the Confederacy. In a letter sent to his brother Pembroke weeks before departing, Thom wrote, “God grant a speedy termination of this terrible struggle, but may it never end until the South has all her right is my most ardent prayer.” Thom would eventually reach Virginia, and he spent the next two years in various volunteer aide positions through the end of the war. With the benefit of a presidential pardon from Andrew Johnson, Thom returned to Los Angeles, to live the next fifty years amassing wealth and high esteem.

Cameron Thom’s antebellum support for Southern interests, and his eventual joining of the Confederate army, was very much keeping with Los Angeles in the early years following its American conquest. Though a county of less than 12,000 in 1860, Los Angeles had a sizable contingent of southern-born residents, a number of which held influential roles. The powerful local Democratic Party machine, known as “the Democracy,” was part of the broader statewide pro-slavery “Chivalry” faction of the party.

The head of the Democracy, southern-born attorney and former assemblyman Joseph Lancaster Brent, would also leave Los Angeles to fight for the Confederacy, rising to the rank of brigadier general. The “fire-breather” Edward J.C. Kewen, the state’s first Attorney General and a former Los Angeles district attorney and superintendent of schools, would be thrown in Alcatraz prison for treason. Henry Hamilton, the virulently racist Editor of the city’s major Democratic newspaper, The Los Angeles Star, was also arrested and held by Federal authorities. As noted in John Mack Faragher’s “Eternity Street—Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles,” the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles—a group of secessionist Angelenos—would be the only company of troops from a free state that would take up arms against the Union.

After the Civil War, Cameron Thom’s California-born wife would follow her husband’s efforts to propagate a racist social order through her work with the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Born Belle Cameron Hathwell in Marysville, California, she was the younger sister of Thom’s first wife Susan, who had passed away in 1862. Belle was 34 years younger than Thom, and according to the early Los Angeles chronicler Harris Newmark, Thom’s goddaughter, whom he helped name.

In January 1899, Belle Thom co-founded the Los Angeles Chapter, No. 277, of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (“UDC”), five years after the national organization was formally organized. The local Los Angeles weekly journal The Capital, in reporting the group’s founding, quotes directly from the UDC’s constitution in laying out the group’s purpose, “To collect and preserve the material for a truthful history of the war between the States; to honor the memory of those who served and those who fell in the service of the Confederate States, and to record the part taken by Southern women, as well in the uplifting effort after the war, in reconstruction of the South, as in the patient endurance of hardships and patriotic devotion during the struggle.”

In California, which historian Kevin Waite notes had more monuments to the Confederacy than any state outside of the South...

Less than six years later, the Los Angeles Times, discussing the upcoming UDC state convention in Los Angeles – to which Belle Thom was a delegate—noted that the state organization had over 1,000 members, and Los Angeles Chapter, with its 128 members, was one of the largest. In 1905, and so too today, greater Los Angeles would boast three different UDC chapters.

In early 20th century Los Angeles, the UDC’s events were a mainstay of the society pages. A 1903 “Ye Halloween Charity Ball,” per the Los Angeles Times, “struck out a note of originality highly enjoyable to the brilliant throng of society folk who tripped the light fantastic and otherwise participated in its joys.” Planning for the Los Angeles Chapter’s February 1905 Charity Ball—“one of the gala events of the season”—began in December 1904. In December 1917, the Robert E. Lee Chapter was set to host on the same day both its “annual bazaar” and “an old-fashioned plantation dinner at which a large number of men from the Naval Reserve Camp at the harbor will be entertained.”

The UDC was not a benign social club, but rather one of the driving forces for enshrining the “Lost Cause” mythology across the county and whitewashing the real cause of the Civil War—the preservation of slavery – from history. In an updated preface to “Dixie’s Daughters,” a history of the organization, historian Karen Cox writes, “UDC members became leaders of a movement that looked not only to past to memorialize the Confederate generation but also to the future in hopes of shaping a New South that, absent slavery, would continue to emulate the Old South in its preservation of White supremacy.”

In California, which historian Kevin Waite notes had more monuments to the Confederacy than any state outside of the South, the UDC similarly played an outsized role in transporting the White supremacist propaganda west. “Women played the leading role in California’s Confederate renaissance,” writes Waite. “They did so primarily through the UDC.” After Belle Thom’s death, the UDC would go on to install the Confederate memorial in Hollywood Forever, where dozens of former Confederates would ultimately be laid to rest, in 1925, and open “Dixie Manor,” an old soldiers’ home for aging Confederate soldiers, in 1929.

...his mayoral biography in City Hall notes his “foresighted investments made him a wealthy man”—was in part a result of his ability to exploit the financial ruin of the Californios, the once-powerful Mexican landed gentry...

Writing three days after her passing, the Los Angeles Times columnist Harry Carr lamented, “The death of Mrs. Cameron Thom takes away one of the last grande dames who ruled California society before the flappers and the movie stars came in. In the 1880s, Los Angeles, in its upper crust, was almost a Southern town. And Mrs. Thom was a leader of that old southern group.” California-born, Belle Thom helped imbue early Los Angeles society with the spirit of “Dixie,” by co-founding a chapter of the UDC that helped enforced a racist social hierarchy far beyond the borders of the former Confederacy.

Cameron de Hart Thom, the son of Cameron and Belle, brought the family’s support for institutional racism squarely into the twentieth century through his work in real estate. Cameron Erskine Thom’s much-heralded prescience and real estate acumen—his mayoral biography in City Hall notes his “foresighted investments made him a wealthy man”—was in part a result of his ability to exploit the financial ruin of the Californios, the once-powerful Mexican landed gentry, through land disputes and lawsuits in the decades after the end of the Mexican War.

In 1870, Thom purchased 2,700 acres of the once 30,000-acre Rancho San Rafael from the blind 88-year-old, Catalina Verdugo, the daughter of Corporal Jose Maria Verdugo, who had been ceded the land by the Spanish empire in 1784. Thom also received 724 acres of Rancho San Rafael from the infamous “Great Partition of 1871," where 28 individuals received 31 different tracts of lands due to questions around book-keeping and actual ownership. Thom would go on to sell a portion of his land to his nephew and longtime business partner, the fellow Confederate Erskine Mayo Ross.

Thom’s sons, Cameron de Hart and Erskine Pembroke, operating from suite 414 in the Bradbury Building in Downtown, went about selling subdivided portions of the old Rancho San Rafael their father had acquired, which at that point had been renamed “Bellehurst,” in northeast Glendale. In the Saturday evening edition of the March 29, 1913, Los Angeles Herald, the Thom brothers ran a prominently sized ad, declaring “Bellehurst – NOT a Fairy Tale.” The ad asked readers to imagine a pastoral lot with unobstructed views, “with all the delights of fresh country air, wholesome surroundings, fine neighbors, clean streets, in a fine residence section…this is no fairy tale.”.

In 1920, Cameron de Hart Thom co-founded the Glendale Realty Board, which would become today’s Glendale Association of Realtors, serving as the organization’s charter Vice President, and later its president. Writing in his 1922 “History of Glendale and Vicinity,” JC Scherer extolled the virtues of the organization in uplifting the city, claiming it as “one of the progressive factors in the development of the community.” The realtors, according to Scherer, “have been instrumental in bringing many families to this city and most of them take personal responsibility in the fact that Glendale is “The Fastest Growing City in America.”

The work of Cameron de Hart’s fellow realtors laid the foundation for Glendale earning the designation of a “sundown” town, where no Black people were functionally permitted after dusk.

The work of the Glendale Realty Board made clear that the “fine neighbors” from the 1913 Bellehurst ad and the inflow of new families were to be exclusively white. As detailed by Douglas Flamming in “Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America,” in responding to a 1927 survey from the all-White California Real Estate Association on how Glendale enforces racial restrictions, the board president William McMillan asserted, “The Glendale Realty Board, and the Glendale brokers, as a whole, cooperate in every way to keep Glendale and “All American City,” and by enforcing race restrictions, we have been able to keep our standard well up in the front of “All American.”

McMillan would go further in the survey form, responding to the question of how “this important problem” could be dealt with by the real estate industry: “In an American town like Glendale, which has the smallest percentage of foreign population of any city in the State, that by insisting on the subdividers putting in and enforcing suitable race restrictions, we can maintain our high standard of American citizenship.” And while a population of Japanese was moving into one part of the city, they were “mostly gardeners,” and “all property carries race restrictions against Asiatics.”

Per the Glendale Realty Board’s rationale, Whites were the only group who were truly American. Discriminatory real estate practices, then, were expressly positive for the flourishing of “American” communities. A decade before the implementation of redlining, organizations like the Glendale Realty Board were devising ways by which to embed discrimination into the fabric of cities. The work of Cameron de Hart’s fellow realtors laid the foundation for Glendale earning the designation of a “sundown” town, where no Black people were functionally permitted after dusk. In a July 16, 1963, Los Angeles Times article around allegations of the city’s racism, Glendale’s city attorney Henry McClernan bluntly states, “no Negroes are living in Glendale. Some come into the city in the daytime to work as domestics.”

L.A.'s Uncelebrated Legacy of Confederacy Still Lives On in 2020 Across the County

Writing in his 1915 “A History of California,” the historian and educator James Guinn gushed, “The life story of Captain Thom is as full of interest as a romance and contains as many thrilling experiences as a detective story or a tale of the South Seas…It is indeed almost a fairy tale from some enchanted volume of ancient lore.” Contrary to Guinn’s hyperbole, the lives of Cameron Thom and his family were not “fairy tales,” but rather ubiquitous reflections of racial discrimination in California.

Cameron Thom was far from the only Confederate to find a home in the Golden State, UDC chapters held sway from San Diego to San Francisco, and most major cities in the state had realty boards devising exclusionary tactics. What is noteworthy about the Thoms is that over the course of roughly sixty years, the family would go from taking up arms against the United States to using real estate to enforce segregation, a clear distillation of white supremacy’s evolution, and adaptation.

There is also Thom’s mayoral portrait in City Hall. Set against an indistinct background, Thom is a well-coiffed and prominently bearded man shown in his later years, staring quietly into the distance. The four-sentence description below the portrait is almost equally devoid of context...

With its longtime identity as a boomtown fixated on the future, Los Angeles has largely forgotten about Cameron Thom. The Long Beach Camp #2007 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans bears the name Captain Cameron Thom. In the Verdugo Mountains, overlooking the city of Glendale in what was once the Rancho San Rafael land grant, is the 2,462-foot peak, Mt. Thom. While not an official designation, and per Glendale historians Katherine Peters Yamada, Mike Lawler, and Rich Toyon, the peak has been called a variety of names, “Mt. Thom” can be found on Glendale city park maps and municipal telecom contracts.

In the South Park neighborhood of Downtown, there are three alleys—Cameron Lane, Catesby Lane, and Pembroke Lane—that bear the names of Thom’s three sons that reached adulthood. In a November 1964 audio recording of her reminisces of early life in Los Angeles, Thom’s daughter Belle Buford Thom Collins, known in the early society pages as “Jette Thom” prior to her marriage to a London theater manager, recounts that her father fell into extensive land holdings in that for years went undeveloped, “Where the Standard Oil Building stands at the corner of Hope and Olympic” west to Figueroa. “The only thing that remains to remind us that it was once his property,” the octogenarian notes, is an alley, “a little strip of land,” Thom had named for his son, Pembroke. That alley is still visible on LA County assessor maps, and while the development around L.A. Alive has reshaped the area, Thom’s three sons can still be found south of Pico.

There is also Thom’s mayoral portrait in City Hall. Set against an indistinct background, Thom is a well-coiffed and prominently bearded man shown in his later years, staring quietly into the distance. The four-sentence description below the portrait is almost equally devoid of context, incorrectly noting his 1854 arrival to Los Angeles from Virginia, and lists a few assorted events that occurred during his mayoralty—acreage set aside for Elysian Park, the founding of the Historical Society of Southern California, a production of “School for Scandal” – meant to convey Los Angeles’s continued emergence into a major city. Left unmentioned is his service to the Confederacy, as well as his ultimately failed prosecution of the 1871 Chinatown Massacre.

The aptest testament to Cameron Thom remaining in Los Angeles, however, is a parking lot. The southeast corner of 3rd and Main Street in downtown was the site of Thom’s longtime home. County parcel maps and city planning documents for the site still read “Property of C.E. Thom.” Where once was Thom’s opulent estate is now a surface parking lot, and where the last rumblings a long-planned second phase to a residential development was an environmental impact report filed back in 2015. The property also serves as the very northwest corner of Skid Row, the epicenter of homelessness in Los Angeles. A line of tents rings the perimeter of the lot.

Civic leaders may not construct monumental structures honoring Thom or other Confederates along Broadway or Sunset, but Union Station was built on what was once Old Chinatown...

That the site of Cameron Thom’s mansion is now the boundary of Skid Row, a mostly Black neighborhood that reflects the structural racism underpinning the region’s unaffordability and housing crises, is the perfect testament to his legacy. Thom and his family, along with other such early “pioneers,” set about constructing Los Angeles for the exclusive benefit of White people.

That the West, and Los Angeles specifically, would be the triumphs of Whiteness was actively promoted by civic boosters. The Press Reference Library’s 1915 “Notables of the West,” a collection of biographies sent to newspapers across the country, begins with “A Word in Advance” from the Los Angeles journalist Otheman Stevens. “Because the great West frowned on white men,” writes Stevens, “and presented to his advantage its redoubts of deserts, mountains, freezing cold, withering heat, vast pathless stretches, inhabited by savage beasts and more savage barbarians, the white man conquered it.” Writing in 1924, the year of Belle Thom’s passing, the longtime Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce trade manager and harbor official Clarence Matson pronounced, “Angle Saxon civilization must climax in the generations to come…The Los Angeles of Tomorrow will be the center of this climax.”

In modern Los Angeles, that Black Angelenos make up 34 percent of the county’s homeless population but are only 8 percent of the total population, that Black and Brown Angelenos are disproportionately arrested or murdered by law enforcement, that pre-pandemic Los Angeles had the largest incarcerated population in the country, that Black, Latinx, and Native Hawaiian Angelenos are dying at far higher rates than whites as a result of COVID-19 and Indigenous Angelenos remain critically left out of the safety net– these are not “accidents” or unforeseen externalities, but rather the result of generations of intentional policymaking that recognized White Angelenos as the only real citizens. These are all monument to Cameron Thom, and the continued legacy of racism central to life in Los Angeles.

Civic leaders may not construct monumental structures honoring Thom or other Confederates along Broadway or Sunset, but Union Station was built on what was once Old Chinatown, the palaces of culture and 1980s high-rises on Bunker Hill sit on the ruins of the multi-ethnic neighborhood redlined and “urban blight”-ed out of existence, and Dodger Stadium dominates Chavez Ravine as a result of red-baiting and broken promises of affordable housing. The creation, and brutal enforcement, of White space that uplifted statues across the South similarly compelled the contours of Los Angeles’s development and growth.

There are plenty of monuments to be toppled in Los Angeles—start thinking about what should be built in their place.

While updating the plaque beneath Cameron Thom’s City Hall portrait can be a minor corrective for the gauzy narratives Los Angeles has devised about its past, such a move does nothing to improve communities that have suffered from decades of antipathy or outright brutality, or for the hundreds of thousands of Angelenos who sit dangerously at the margins due to the convergence of COVID-19 and structural racism.

To dismantle the legacy of Cameron Thom, Los Angeles, for the first time in its 239-year history, must be reconstructed in a way so as to fully and unambiguously recognize the humanity of its entire populace. This work has been ongoing for generations, but an expansive vision for a more just Los Angeles can be seen in the hundreds of thousands who have taken to the streets in the past month; in Professor Melina Abdullah and Black Lives Matter’s presentation to the City Council calling for a budget truly reflective of people’s needs and values; in the work of the JusticeLA coalition other community activist groups pushing the county towards decarceration; in the tireless advocacy of the LA Street Vendor Campaign and the vendors themselves to demand recognition that was for too long denied; and in the envisioning and creation of the 1.3-mile long Destination Crenshaw in the heart of historic Black Los Angeles, that, as chronicled by Sahra Sulaiman, “Will not just be a place to celebrate unapologetically Black contributions, but also a place where it is safe to be unapologetically Black in Public: A Black Space, full stop.”

There are plenty of monuments to be toppled in Los Angeles—start thinking about what should be built in their place.