The work of photographer Joseph Rodriguez has been featured in Time, Life, National Geographic, and the New York Times, to name a few. His career has spanned decades and continents, with major documentary photography work done in places such as Romania, Spanish Harlem, Mexico, Kurdistan, Sweden, and East Los Angeles. Born and raised in Brooklyn, Rodriguez's seminal book East Side Stories explored Los Angeles gang life with an intimacy that hasn't been matched. Currently teaching at the International Center of Photography, he has taught photography, and exhibited his photographs, all over the world. We spoke to Rodriguez from his home in New York City to discuss his early career, what drew him to Los Angeles, and the profound effect his documentary work has had on him, his subjects, and the community.

How did you get started with Photography?

I love the movies and the reason why I loved the movies, the cinema, was it was a way for me to escape. So what I saw on the screen as a little boy was embedded in me. Photography comes much later, after I came out of Riker's Island.

I was a messed up kid at that time. I fell into the streets and all that stuff. So what happened is, I came out of jail and I knew I had to fix myself. Fix myself meaning that I had to deal with my addiction. My heroin addiction. So I immediately got into a program, and I got a job through that program. It was a different time in America. It was the time of affirmative action, so there was a possibility for those that wanted to grasp a better dream so to speak.

There was an opportunity in our community here in Brooklyn to take a photography class, and I went to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum where they had a basic black and white photography class, and I immediately fell in love with developing film. Now, I was not serious, yet, not at all.

But what it did was get me away... it moved me away from all the bad guys. I basically went to a different neighborhood, I worked, I got my little camera, I developed my film and that really excited me because for the first time in my life, I had a chance to speak; to say, “Oh, this is my photograph. This is mine.” So it was a personal connection that way. Nothing serious, it was just buildings and trees, the Brooklyn Bridge, very amateur but that gave me a sense of focus and believe it or not, I eventually made a U turn.

I got off of drugs and started going back to school. I got my GED, got into a college adapter program, it was a really cutting edge program at that time to teach you all the subjects that you needed to be able to get into college. I actually do have a camera at this point, but I’m focusing on moving forward. I went to CUNY New York City Technical College, and I studied graphic arts technology.

So now I need to get a job. I need to do something, I wasn’t ready to do photography as a profession yet. So I started working for various color separation houses, that’s what they were called back then, and we started to do color separation for the New York Times Magazine's ads for Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein... So fantastic. It was still the photographic process to me, right?

Take somebody’s art, advertising art, bring it to press. I learned the full color process and had clients and became an assistant account executive. They gave me my own accounts, and I'm making a lot of money. This is now around 1980.

I keep at it, and ’81, ‘82, ’83, I worked in the graphic art printing industry here in New York City, which is quite big. So making all this money... I started flipping back into partying and late night discotheques, and stuff like that. And I said, “Oh this is not for me, Joe.” So I quit. I took another class in photography, now I’m older and I went to the International Center of Photography here in New York City which was quite big back then.

So that's when you started there, the institution where you now teach?

Yes, I took one class, Color in the Street. And it was color slides, which I could do because you get to process, and it excited me once again. Now, I told my mom I’m going to quit my job and she freaks out. I didn’t tell her, but I go back to driving a cab because during those years of changing myself, going to school and getting out of addiction I drove a taxi cab...

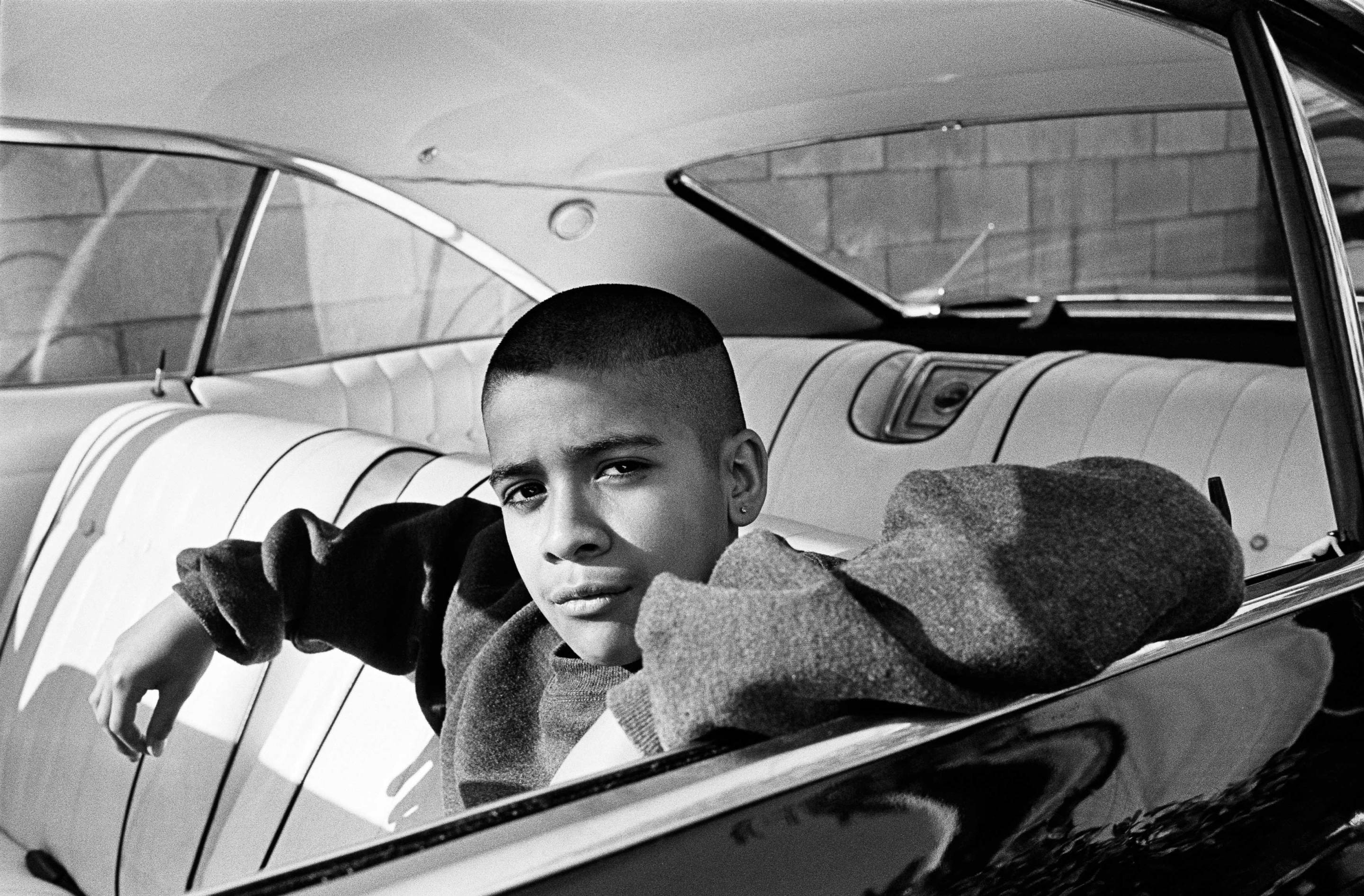

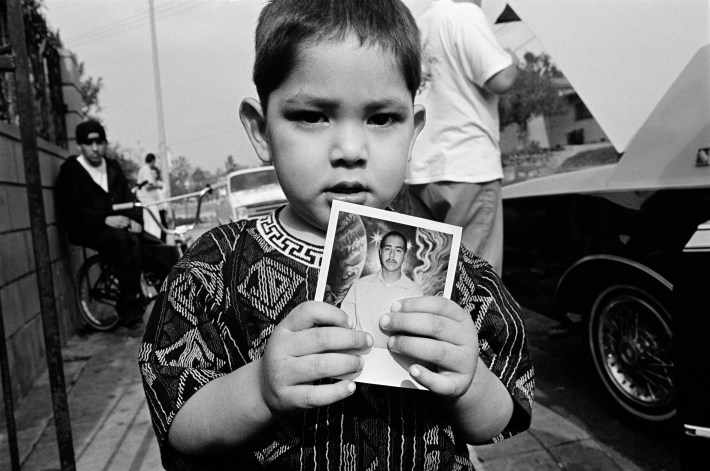

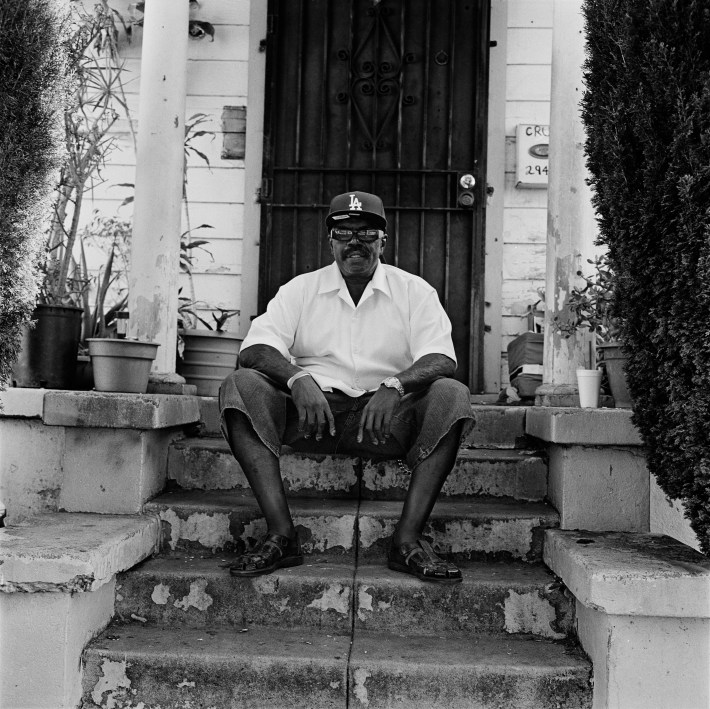

East Los Angeles, CA, 1993

In Manhattan?

In Manhattan, Brooklyn, all over the city. And I took a part time job with a friend of mine who had an art moving business. One of my trucker friend's clients was the Freidus Ordover Gallery, Soho, NY where Larry Clark was installing his exhibition. It was Teenage Lust, great stuff, powerful stuff, and I went up to him like I was going up to Jimi Hendrix or something. I swear to God... I said, “Can I talk to you for a second?” And he brushed me aside. Then we got all the stuff loaded in the truck and I went up to him again.

I just have to talk to this guy. He doesn’t remember me. He doesn't know me. There was no personal connection, but I said, “Look, I really connected to your work and I really want to be a photographer like you.” And he said three simple words “Go take pictures.” And from that day on, I think it was ’83, I went up to ICP and I said, “Look, I’ll do anything here. I’ll clean the dark room, I'll do whatever.”

And I did that throughout the summer and I worked really hard instead of making pictures. They had a scholarship to study for the photo journalism documentary program in 1984, and I worked for it... I was still a taxi driver, but I kept trying to take pictures and learn more, and learn more and learn more and that just opened up a whole life to me, it really did.

At this time did you consider yourself to be an artist?

No. Not yet. I needed to find out who I was and it took awhile. I mean, I started to figure stuff out, get a job and say, “Okay, I can do this, and that would be everything.” But when it comes to this journey as an artist, or in this case, I’m really trying to be a documentarian, there’s a lot to learn.

So I’m very humbled but I had great teachers then. We had Fred Ritchin, we had Sebastião Salgado come to our class, Bruce Davidson... and then here I am, this kid from Brooklyn and I’m sitting next to all these international students in my class, students from New York, from Paris, Canada. It’s still like that today. It’s just a marvelous school.

It opened up a whole new vision for me. I met this Swedish woman who turned out to be my wife and we had two beautiful children, and suddenly I’m graduating, and I’m saying, “What am I going to do now? What project can I really lay my hands on here?” And I was always very close to this place called Spanish Harlem here in New York, my uncle had a candy store there. It's kind of Westside Story, kind of crazy you know?

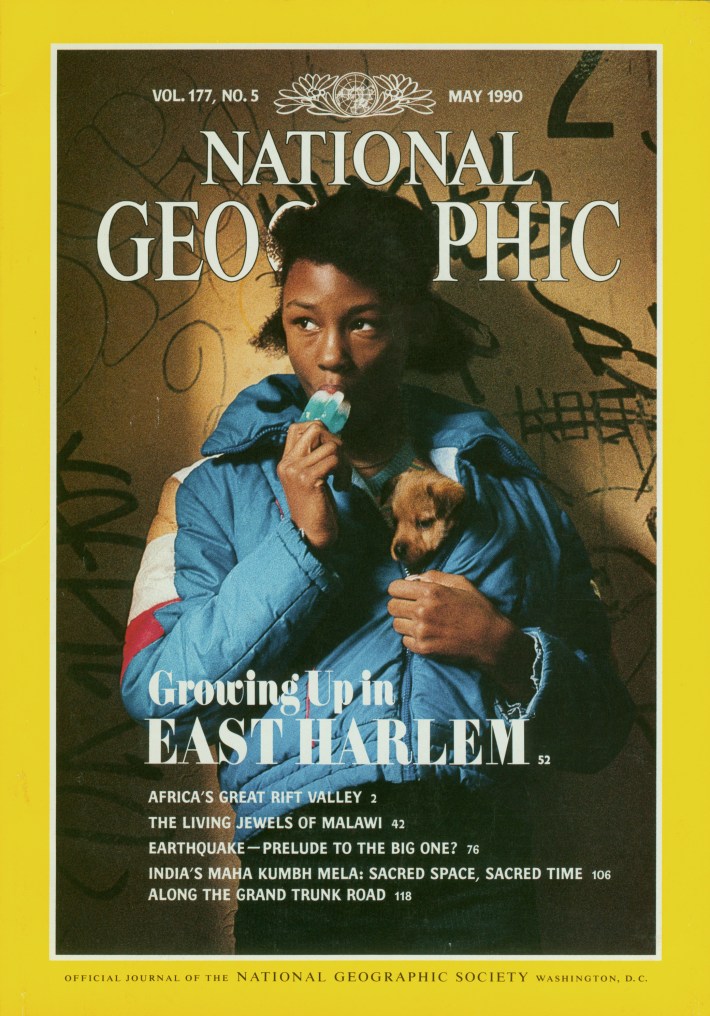

I continue to work on my project while working for the Black Star New Agency, and later, after I showed some of my Spanish Harlem project, the president of the company said, “Hey, let me see what I could do with this work.” They sent me around to all these different magazines, and then down to National Geographic, and believe it or not they pick me up and the story ran. May 1990, it was a cover story and now this is the beginning of the career...

And that was the first…

That was the first documentation.

Do then did you start to say, okay this is a career for me, I’m going to make it?

When you start out as a photographer, like a lot of guys even in L.A, you do weddings, you do whatever. You go on this, you go on that, you do whatever you can sort to make a little money in your pocket, but my main focus is to go out into the world and tell stories.

What brought you to Los Angeles? How did that happen?

All right well, just to fast-forward a little bit here, after my National Geographic story was published, I married my first wife Jessica and we had twins. I had no steady job, I didn’t know what to do, so we moved to Sweden. And that changed everything. When I was living in Stockholm, I missed America. I lived there from’88 to ’92.

So what brings me to L.A? Well, I always had this dream of coming to Los Angeles because I loved the music and all that, but I'll tell you the real trigger that sent me there. The trigger that sent me there was everything that was coming out in terms of gangster rap at that time. So NWA, and all these guys were coming up because they were speaking about what’s really happening on the streets. While living in Europe then, while beginning my research, I couldn’t find anything about gang culture in Los Angeles except in the music.

So then when the riot happened in 1992, I was in New York with my kids to see Grandma and I said, “Oh, I’d like to get out there and see what it’s all about.” We went back to Sweden instead, but the idea, originally was to go out and do the real story, actually hanging out with the gangsters, drive the bombas, and all that...

But you know, what opened my eyes was all of the gun violence that was happening at that time. That’s what really brought me in. It wasn’t an assignment– it was self-assigned. I’m a very kind of different kind of photographer where most of my projects that you’ve seen so far are self-assigned.

Did you have any connections you could call on?

None at all. No. The first thing I did-- I found a small magazine clipping from US News and World Report, and it said that the Bloods and Crips are coming together for a truce, and Jim Brown was trying to help, and it mentioned a Community Youth Gang services on Western boulevard. They moved now. I think they’re still around but they moved and then they changed their name. So I flew in to L.A. at night. I stayed at the Hotel Figueroa which is still there isn’t it?

Yeah.

So, you know, I’m crapping in my pants. Sorry to be so crude but you know, I never drove seventy five miles an hour, eighty miles an hour before at night in my life! And so I get there and I don’t sleep. I turn on the news, I see what’s going on, there’s gang funeral after gang funeral and many other gang related stories on KCAL Televison news. Then I say, “Well let me just get out here.” So I went to the community youth gang services, and I sat there for almost a week before anybody would talk to me because I didn't have any money or connections.

I wasn’t on assignment for the New York Times or L.A. Times-- those media corporations have big money and they can hire these kids to walk them around and show them around. Eventually, one of the guys there, who was an ex-gang member, brought me to his neighborhood. I didn't have money to pay, but I have this history in America. I knew what to ask families. So the first question I would ask would be, “Tell me about the riots in ’65. What’s the difference between ’65 and today?”

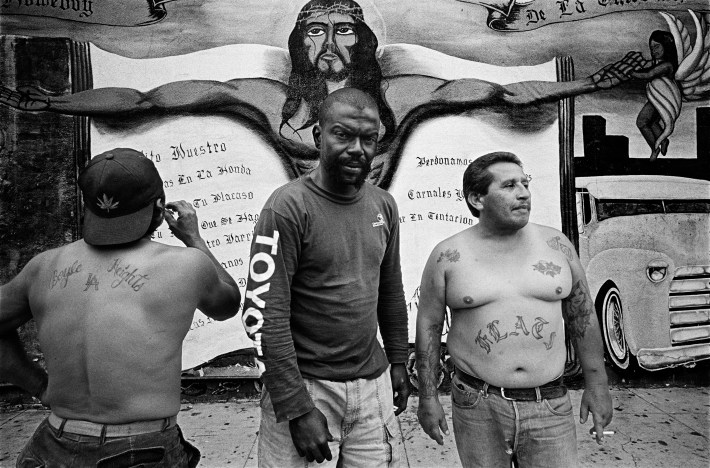

So there’s this just a whole bunch of stuff that I was able to learn from families there... LA is overwhelming, it’s huge, so I started moving around South Central, Compton, Watts, East L.A, everywhere.

That was the first trip. That was in May 1992, I stayed five weeks. I worked like a dog and then I left. I came back to Stockholm, I looked at the work, I sent my work to Black Star in New York, and they said, “Okay, wow this is big, this is big.”

I said it to myself, too. This is really, really big. So then I moved to L.A. in September of ’92 and I stayed in L.A., in Silver Lake, for almost three years.

When you looked at the work, what is it that made you say, “Okay, I have to devote years to this?

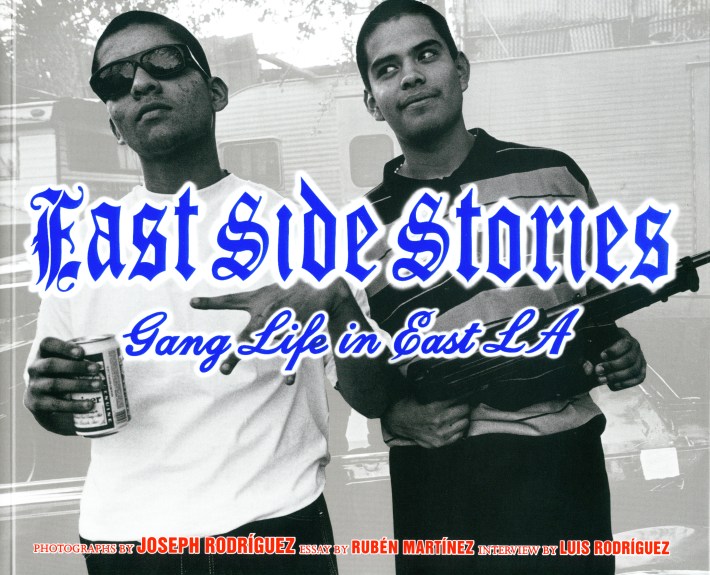

Family. Because look, it’s easy to go shoot somebody holding a gun. Very easy. But what was hard was I wanted to get beyond the fence, beyond the door, and I write about that in my book East Side Stories. It’s a collector’s item now. It was the most stolen book in a Silver Lake bookstore; they put a chain on it.

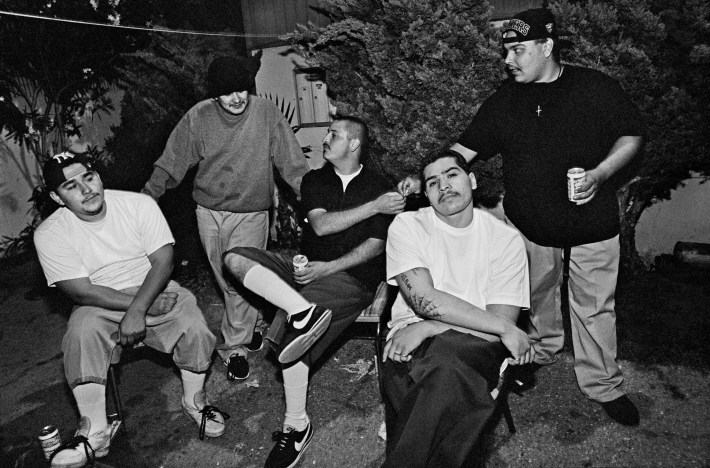

The core was always family and that’s how I started on my first project here in New York, in Spanish Harlem. You’ll see that theme no matter where I go in the world. I just wanted to see if I could humanize people... it’s a little complicated when you go into someone’s life, the family life.

For example I learned from the many generations of gangs. I met this grandfather who said in 1926 they started the gang. I was like,“Woah.” So I knew that there was something larger here to speak about. Not just the guns and the violence. The families, the history.

What kept you there for so long?

In 1993 I got an assignment to go to Bosnia, and at that point I was photographing in Boyle Heights and I’m working with the gang called Evergreen which is right across the river, and I told this one twelve year old kid about the trip. He said to me, the twelve year old kid, “Why go to Bosnia? You got Bosnia right here." And so I stayed.

Damn.

Yeah.

You talk about family and that's what links all your work together. Where do you think that came from? Is that something from your own past that you see in these other families?

Definitely. I mean most artists can pull out something that's deep inside their experience from when they’re younger. Not everything is just kind of "owned" so to speak.

Right. Right.

I just saw this documentary about Marlon Brando, it just hit me so hard. He said, "when no one shows you how to love, you don’t know how to have love". If the family is falling apart... you can see the core of this man, you know? I mean all the trauma and drama that happened to him over his life but you then see his parents and what they were all about... and you understand.

So you know, I had a step father who is a drug addict and I used to see that when I was a kid. I wasn’t a gang member myself, but I have the foundation, at least I can have these conversations with some of the families.

In the streets? In their homes?

At the kitchen table.

You have common ground...

Yes, but you also have to be on the outside too. Very much so, otherwise you get too close then you can’t…

You have to still be documenting, always.

Yeah. That’s what I told my students anyway (laughs) so…

You’re coming from the outside; you’re coming from East Coast, From Brooklyn. Were you aware of the differences between the images you had made at East Coast and West Coast?

It is different. My family and the people that I photograph were Puerto Rican, on your coast they are mostly Mexican, right? Very hard to break into. Very hard, and I can honestly tell you, and I am not lying to you that in the two years of documenting this project, every day, every single day, someone thought that I was a cop. I had to constantly be proving myself, but you know, I just – I'll tell you what really pushed me forward.

What was that?

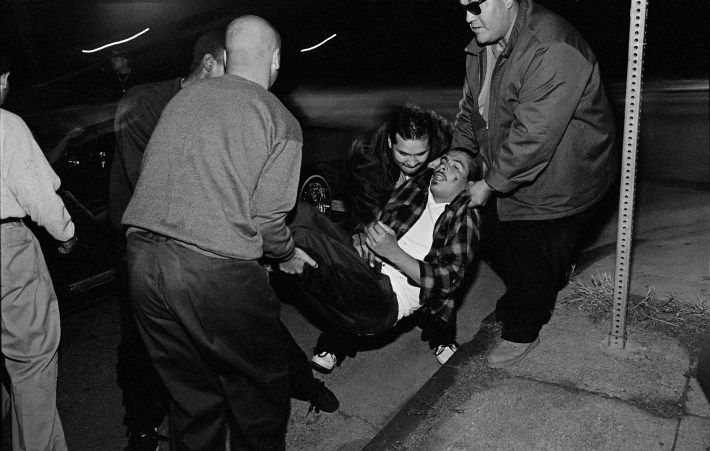

In ’92, the first trip, I saw a newspaper article in the Times. This two and a half year old baby was shot. They said there was going to be a funeral, right? And so I found out where the church was in East LA. I didn’t know anybody, and I went up to the church and I said, “Hey do you know the family– can I interview the family?”

They gave me the address and I went cold, and knocked on the door and I sat at the kitchen table with them. They pulled out pictures of their baby, we prayed together and that family... it’s a very important picture in the book. There’s a baby in the coffin.

This is not a very nice picture but it is an important one. And I have two children now at this point so I’m not – I’m feeling more like a parent with the camera as opposed to just a photojournalist and I didn’t want to be (...)

A lot of photographers were kind of just, it’s part of the job and you just kind of parachute your way in and parachute your way out. I couldn't do that. So I’m sitting at the kitchen table and this mother who had just lost her little son says to me, you have to tell the story. You are here for a reason. And that became such a heavy weight on me.

It became a sort of mission, once you heard that.

Yeah. You know, it’s a big responsibility when somebody says that because where are the people? The media? Where are they? Where are you guys? And that was just - and I heard that from quite a few mothers and fathers...

How did you decide that the job was done, and when was that?

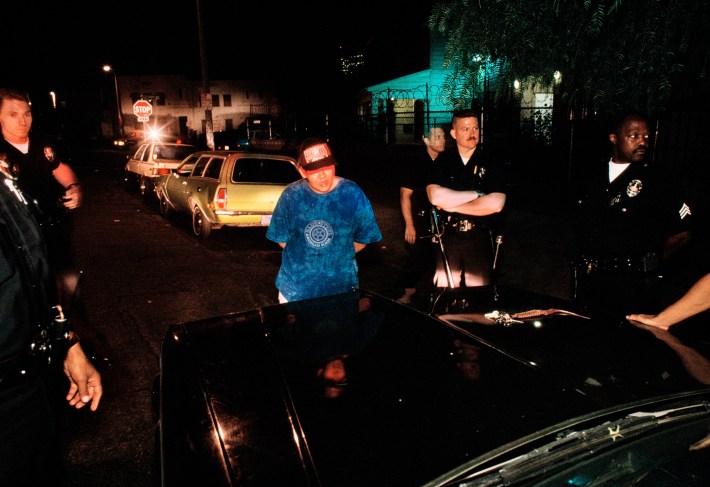

In ’94 I got an assignment to photograph Rampart LAPD for the New York Times magazine, and I did a cover story. You know what happened with Rampart, I don’t have to tell you.

Yeah. Definitely. That was huge out here.

People have seen Antoine Fuqua's film Training Day, and Woody Harrelson in the film Rampart, and some of your readers have seen it in real life. When you include the gang stories and the LAPD stuff, we are talking at that point three hundred rolls of film. There’s no digital then.

That’s a lot of film. And I needed to stop... to be able to see what I had done, because I'd been working and working and working and I have to look at these pictures. I’d send my film in New York then get back little prints, so at least I could give something back to the people I was photographing. But I needed to stop and look.

When the interviews and photos were printed and came out, what happened? What was it like?

Intense. I mean, one picture, you’ve been on my website I guess, right?

Absolutely, yeah.

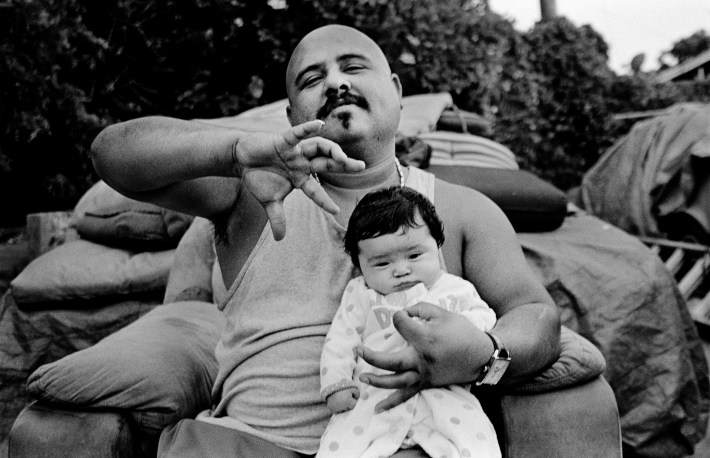

So the picture of Chivo, with the baby and the guns, I can tell you the story of that picture...

I was working with Chivo for about a year and a half. We go to quinceañeras together, we hang out together, we go shopping, we go to Ob-gyn with his girlfriend, because I had a car and he didn't. It wasn’t just taking pictures... I call them that morning, he goes (and this always happens to photographers), “Where were you last night? Oh my God!” I say, “What happened?”

So what happened was there was a shooting with a rival gang. He says, “I had my homeboys in my house” That’s why all the guns were in there. So everybody was standing by the windows there. So I walked in and he’s playing with his daughter, it was not set up. I’m sure a lot of people think that I ask people to do that. I don’t do that. Just for the record. There was a USA Today photographer, he worked at the community gang services and would hire some Bloods to go out asking for guns, and he'd take the shot, and that’s unethical, right? So I don’t work that way.

So Chivo... I get there and I see this whole thing, and I see all the guns and I say, what’s this all about? He says “Well, here’s my daughter right?” And speaking for his daughter he says, “Okay, what will the caption for this one be? Last night they tried to shoot at my father for the fourth time."

Because look, I don’t like guns, I don’t like what they do to people. They take people away from us so if there is going to be an assault weapons ban, I’m going to support that with this photo if I can.

So when those pictures went up, I started getting emails from all over the United States. From parents, cops, students, brothers, sisters, cousins because you know how big this stuff is in Texas, in Arizona, in Utah? And I had no idea that it would be as big - because unfortunately at that time, (and maybe still) your town is like the gang capital of America.

Then here I come back to New York and this time in the New York Times they're saying “it isn’t going to happen here.” Yeah?

Well guess what? It’s all over the place. Latin Kings, Blood and Crips, I mean, it’s in Ohio, it’s in Kentucky, it's everywhere so that’s why the book became such an important document. I'm proud to say that it’s in the University of California libraries system. It’s also at the San Bernardino Juvenile Hall library, there’s a librarian there that supports this work.

How did the publication of East Side Stories impact your subjects?

I came back with books, and I gave them books. Are you kidding me? Man, these guys are so proud of that book. They are still calling me now, we’re in love with that book, man. "I want to buy that book!" You know, stuff like that. So, I mean of course we can’t please everybody, but sometimes when you’re telling a story, it’s about a larger picture.

I always wanted to use this book as an educational tool-- that is why working with the author, former editor at the L.A. Weekly, and now professor Ruben Martinez was important. We really worked hard on the text, I did the pictures and then went back and introduced him to the family, he went to the neighborhood, and he also worked with the some guys in Evergreen. We went and interviewed or we sat down together with Luis J. Rodriguez who wrote Always Running. He is very famous. He is from San Gabriel and was a gang member himself who later went to Chicago, and he presents his story in East Side Stories.

What about the impact on you?

The impact on me - well you know what the word PTSD means... I was pretty messed up. I came back to New York always angry. Hard to be around. It took me a while, it took me a while to kind of shoot that away. You know, I played my music loud and my neighbors were pissed off and you know? Because I was really there, I was really there for a long time.

Did you end up going back to see some of the same people in later years?

Yeah. Yeah sure. I’ve been back. I was back in ’95, I was back in ’96, I was back in ’97.

I mean L.A is our second home. I miss L.A so much right now. You have no idea man. I’m dying over here. Dying in New York, you know everything from just being able to smoke what you want without getting arrested, to eating good food, going to the desert. I used to go to the desert a lot. That’s where I find peace...

2012 was twenty years when I decided to return to Los Angeles, and I was so nervous, and I said you know what? I’m going to go back to Evergreen. I couldn’t do everything and retrace everywhere I had been in the 1990s, because I didn’t have enough money, but I went back and I bought a video camera and I made four different interviews, Steve Blount is the African American brother, the older guy in the book.He’s first generation Evergreen.

When I met Steve, he was using heroin, it was bad for him, and when I came back fifteen years later, he’s been clean, a new man, not a criminal or an addict. You see here’s the thing. This is just very important to me. If I’m going to show the darkest dark, I need to show some hope. For example, the last picture in the book is Chivo at a job on the phone and that was VERY important..

When you met Larry Clark in that gallery and he told you to take pictures... what do you say to the young, especially to the young Latino kids who see your work, and want to be like you?

Oh, I email them all the time. I’m on Facebook all the time. If you are serious and you want to talk about your story, I'm there. I believe we have to own our own story. It gives you a sense of pride and a sense of dignity to be able to do that. You can take Instagram if you want but I think if you want to be something more serious... let’s talk about what you want to do and let's do it. So I guess I am a role model in that way because I never had one and I take photography very seriously.

I have one last question for you. Which is what’s your favorite place to get a taco?

Jeez... hard to choose. Los Cinco Puntos, and there used to be a truck that parked near there too. And another truck, over by Evergreen Park, forget the name. Love the L.A. Tacos man...

East Side Stories

Rampart