From one of the most prosperous oil towns in America to the so-called “Slum by the Sea” to Silicon Beach, Venice is a town that has gone through more dramatic transformations than any place in L.A. Let's take a look at some of the more significant moments in its modern history for our weekly Neighborhood Project.

History tells us the lagoons and bluffs above the sea were previously inhabited by Native Shoshone and Tongva Gabrieleño societies who hunted and fished there and shared their knowledge of the region with the colonizing Spanish.

In 1839, the Rancho La Ballona land grant was awarded to two pairs of brothers whose families already had a long history in this region: Ygnacio and Augustin Machado and Felipe and Tomas Talamantes, who had been using the land for grazing cattle for the previous 20 years. The land included much of L.A.'s contemporary Westside, including Mar Vista, Palms, Culver City, Ocean Park, Marina Del Rey, Playa del Rey, the Ballona Wetlands, and today’s Venice, a southern portion of which was contained within a marshy lagoon. Today, you can see graves of many Machado and Talamantes family members in Santa Monica’s Woodlawn Cemetery on Pico Boulevard.

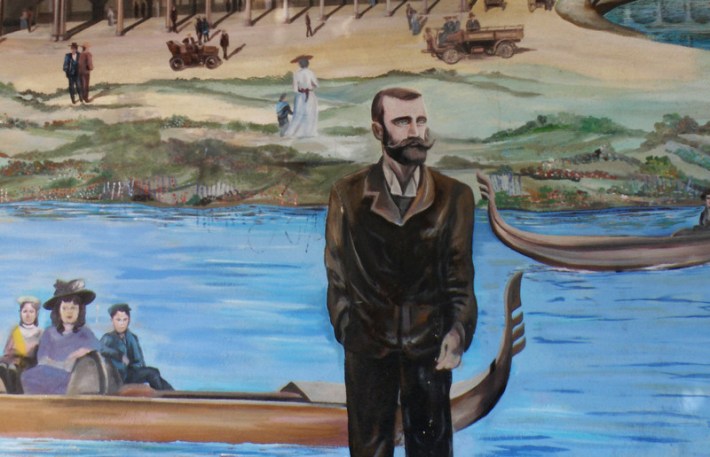

Enter Abbot Kinney, a New Jersey-born, D.C.-raised beanpole who became a polyglot in his teens after an extensive trip in Europe, where Venice, Italy, among many places, clearly made an impression on the young man. As a part of the Maryland National Guard, Kinney headed west on a surveying expedition to map Sioux lands in the Dakotas, before joining his brother’s tobacco business in New York. The Kinney Brothers Tobacco Company sold Southern tobacco. Also, it imported it from abroad, which took him to Egypt and Ottoman Macedonia, a trip that unexpectedly continued as Kinney made his way through Europe, India, New Guinea, Australia, and Hawaii, eventually stopping in San Francisco on the way home, where his return was impeded by snow.

Kinney chose to stay in temperate California. An asthmatic he visited a game-changing summer health resort called the Sierra Madre Villa Hotel in the San Gabriel Valley. He didn’t make a reservation and slept on a pool table. When he woke up symptom-free, he bought a 550-acre property nearby and called it Kinneloa.

Kinney, with his homie John Muir, was instrumental in protecting the forests of the San Gabriel Mountains, and the two friends established the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve. Around that same time, Kinney and Helen Hunt Jackson wrote a report for the U.S. Department of the Interior on the living conditions of the California Mission Indians, which led to the Mission Indian Act of 1891, which recognized the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians’ inherent rights to self-govern as a sovereign nation and helped establish and confirm Southern California reservation lands.

In 1886, Kinney’s wife, Margaret, unhappy with staying in the SGV in the summer, helped push the couple to Santa Monica, where they built a summer home. There, Kinney started the Santa Monica Improvement Company and a tennis club. In 1891, Kinney and Francis Ryan, his partner, took over the Pacific Ocean Casino and bought about two miles of property along the beach, where they built an amusement park and resort of sorts with its own pier, golf course, racetrack, and boardwalk they named Ocean Park. At the turn of the century, Kinney bought a tract in today’s West Adams to create Kinney Heights, where today you’ll still find many historic homes from the time. When Ryan croaked, his half of the land was sold to other partners, while Kinney was unhappily left with the marshy lower half of the land through a coin flip. No problem, he’d build Venice on the site and change the history of Los Angeles as we know it.

With visions of northern Italy’s famous Waterworld of a city dancing in his head, Kinney dredged the marsh by creating canals and created Venice-Of-America along the perimeter of the lagoon, which was located where the present-day Windward Circle traffic roundabout can be found. A boardwalk town opened in 1905; it was alive with an auditorium, ship restaurant, hot salt-water plunge pool, and dance hall, as well as a block of Venetian architecture and of course, the big old beach that drew crowds on the Red Line from around the city. By 1910, Kinney’s Pier had opened, and the boardwalk was rich with games, attractions, freak shows, fun houses, roller coasters, and a miniature steam engine that would take you around the park. Competing piers in the area included The Sunset Pier (1921) and the Lick Pier (1923).

Kinney also stocked his system of canals with imported gondolas and gondoliers, while his Windward Pier featured a saltwater aquarium. The whole grand attraction rivaled Coney Island, even if Kinney and his neighbors weren’t always stoked on some of the more lowbrow attractions gathering there nor the rabble it drew from far and wide. If you’re already getting Rick Caruso vibes, Kinney did one better, eventually taking control of local politics and changing the name of the whole area from Ocean Park to Venice in 1911. He was permitted the right to build a 6-foot breakwater to shield everything from the large body of water to its west.

Margaret Kinney's wife died in 1911, and the man himself followed in 1920. A month later, with the business now under the watch of adopted son Thornton Parillo, the pier was almost destroyed by a fire, then quickly rebuilt as the Venice Amusement Pier. Venice's first golden age was essentially at an end, with its founder no longer at the helm.

In 1925, a year after Kinney’s mini railroad shut down, Venice officially became part of Los Angeles, which wanted a beach in its city limits. Venice’s roads, water, and sewage systems were in dire need of repair at that point. The city cracked down on the canals, deeming the stagnant water a health hazard, which caused most of them to be paved over in 1929. The remaining canals were mostly neglected and in disrepair until being restored in 1992. Today they are now built up with homes owned mainly by the mega-rich. The pier’s lease was not renewed in 1946, leading to its demise, while Thornton bailed for New Jersey, where he’d write about his father’s colorful life. Very little remains of Abbot Kinney’s vision today save for his breakwater, some adorable buildings and street names, some of his Venetian arches, and of course, the Venice name and legacy.

Oil! In 1929, oil was discovered just south of Washington Boulevard, leading to the construction of 450 wells in two years. This would clog the remaining waterways of Venice and provide a brief lifeline to the town during the Great Depression. Most wells were capped by the 1970s, with the final one sealed off in 1991. Long before then, L.A. had long lost interest in Venice, considered a relic of the past and a city in neglect, perhaps like many locals' attitudes about the Walk of Fame today.

Last year, a historic statue and monument honoring Mexican Traqueros and their contributions to the American railroad system was approved by the L.A. City Council to be installed in the middle of Venice's Windward Circle. When the 405 Freeway was built in the late 1950s, many neighborhoods historically housing Black, Mexican, and Mexican-American families were destroyed, scattering their residents around the city. Many who chose to stay by the coast gravitated towards Venice’s suburban Oakwood neighborhood, which would become a Black enclave on the Westside, sometimes referred to as a “servant’s zone” by their wealthy employers. Here, Black families could live without many of the risks, harassment, violence, and outright rejection they would face in other Westside and L.A. neighborhoods.

In the 1950s, the nasty sobriquet “Slum by the Sea” was being used by some to describe Venice, with very little civic improvement being made. Instead, its cheap bungalows made for appealing housing for artists, bohemians, and European immigrants, including a large population of Holocaust survivors, domestic workers, and manual laborers.

Over the decades, Venice has been known for nurturing Beat Generation poets and artists, musicians like The Doors, Jane’s Addiction, and Suicidal Tendencies, battling gangs like the Shoreline Crips (one of the earliest Crip sets) and Venice13 (whose roots stretch back to the 1950s), as well as Nazi punks, and many of the pioneers of modern skateboarding. If you remember Venice in the 80s and 90s, you know it could be a rough town where strolls along the Boardwalk or a visit to Abbot Kinney Boulevard could become very dangerous as rival crack dealers and gangs shot it out. Matcha oat milk soy lattes were impossible to find. It was hardly rare to find writers describing Oakwood as a "war zone" at the time. At the same time, the Boardwalk continued to be a vital, vibrant slice of the city, known for memorable local legend entertainers like the shit-talking chainsaw juggler, the indomitable Harry Perry, that old guy with the ponytail who plays piano really really well, and that DJ with the sick cuts.

As the gang violence of the 90s gradually decreased in the new millennium, with many Westside gangbangers getting raided and arrested through strict gang injunctions or forced out to other neighborhoods by gentrification and soaring prices, Venice gained a new luster for the well-heeled. White homeowners and celebrities began trickling into the area to buy and rehabilitate old houses in the 80s and 90s. Art studios and indie shops are increasingly shuttered to make way for high-priced boutiques and trendy fine-dining restaurants. The nail in the coffin arrived as Google and other tech companies landed in Venice, seducing hordes of lesser start-ups to follow suit, sometimes for the appeal of the zip code alone, and leading to the nauseating nickname of Silicone Beach and the proliferation of douchebags in high fades and shorts with disturbingly micro inseams.

At the same time, Venice’s strict zoning rules and a growing surfeit of rich NIMBYs helped kick or keep many locals out of the boom, with homelessness exploding by more than 1100% in the neighborhood between 2014 and 2020. During the COVID pandemic, a tent city multiplied rapidly along the Venice Boardwalk a month before the shutdown,while a 154-bed transitional housing shelter was opened at the former Metro bus yard on Main Street. Homeowners in the area seemed to complain loudly about them both. Today, affluent new homeowners, many transplants from other cities and states, have found a way around the strict zoning laws by building cookie-cutter modern monstrosities of homes resembling futuristic barns, taking out old neighborhoods along with their charms. Still, the spirit of Venice somehow survives, mainly along the Boardwalk asphalt and in the localized lineup at Breakwater.