[dropcap size=big][/dropcap]Terry Gonzalez grew up hearing stories of a much different Boyle Heights than what the neighborhood, and Los Angeles, looks like now.

“My parents told us stories of my great grandfather working on the old Southern Pacific rail line when we were kids. When this was all orchards and vacant land,” she says, sweeping her arm around her quaint home in Boyle Heights on a sunny spring day. The same home she grew up in. A home her parents moved to from their parents home just down the street in the 1950s, a home where she now raises her children in.

“My parents were very outdoorsy people,” she says. “They loved gardening. We were always outside in the earth. I remember me and my friends from the neighborhood getting in mud fights. Those were our fondest memories growing up until we found out everything was toxic.”

Gonzalez grew up with asthma and later suffered from dizzy spells. At 15 she developed tumors in her uterus.

“That’s not something that’s very common for fifteen-year-olds. And everyone else who’s lived in this property has gotten cancer or has had strokes,” she says, including her brother, her parents, and herself.

Frustrated, Gonzalez went to see a toxicologist who she says was confounded by her medical problems. “The toxicologist eventually blurted out, ‘Maybe it’s something in your environment?” she says.

A year or two later, Gonzalez woke up to a layer of unexplainable dust on her car. She talked to her neighbors, and to the priest at Resurrection Church, right across the street from her house. Weekly meetings with similarly concerned community members started forming, and soon enough, they started to talk about Exide Technologies.

The DTSC had found that Exide had been emitting dangerous levels of lead and arsenic into the community and unsafely transporting and disposing of toxic waste products.

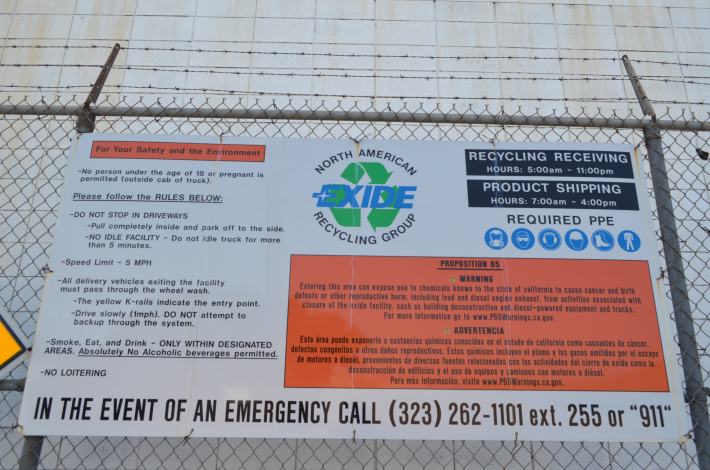

A little under two miles to the southeast of Gonzalez’s home lies 2700 South Indiana Street in the city of Vernon, the site of what until four years ago was the Exide battery recycling plant. Since 1922 the 24-acre industrial facility has been operating off and on as first a metal fabrication plant early in its life. In the 1970s it was bought by a company called National Lead and turned into a lead battery recycling plant.

Lead battery recycling is a process where old car batteries are smashed apart and then heated in smelting furnaces to remove all but the lead particles, which are then recycled and sent off to be made into new car batteries. In 2000 the Milton, Georgia-based company Exide Technologies bought the plant.

Exide had been racking up more than 100 violations from the state’s toxic substance control agency, the Department of Toxic Substances Control, or DTSC. The DTSC had found that Exide had been emitting dangerous levels of lead and arsenic into the community and unsafely transporting and disposing of toxic waste products. As those violations were growing DTSC did little to stop the company from poisoning those nearby communities.

Four years later, only 788 homes have been cleaned out of thousands of homes identified as toxic.

But even worse, those communities—Boyle Heights, Commerce, Maywood, Huntington Park, East L.A., and Vernon—were largely unaware that they were living and breathing those dangerous particles in the air.

After years of community lead protests that put pressure on both Exide and the DTSC by the community group at Resurrection Church, and activist groups like Communities for a Better Environment, and East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, local, national, and international press caught on to the story of the poisoning of hundreds of thousands of residents of east and southeast L.A.

Then, in 2015, the U.S. District Attorney’s Office presented charges against Exide. Exide settled, accepting responsibility for decades of toxic pollution, and agreed to shut down their operations in Vernon. Shortly after the DTSC began planning the cleanup process, testing homes around the facility for lead contamination in the soil, and beginning to remove and clean the contaminated soil at the abandoned Exide facility.

Four years later, only 788 homes have been cleaned out of thousands of homes identified as toxic. What’s resulted in the wake of the plant’s closure since 2015 is a complex and infuriating tangle of bureaucratic, legal, and political wranglings and outright corporate and governmental malfeasance that have left people in southeast L.A. frustrated, angry, and simply asking why is southeast L.A. still being poisoned?

DTSC had also performed ten enforcement actions against the company and cited more than 100 violations of California’s hazardous waste laws

More than four years later those same communities that were wronged by Exide feel just as wronged by the DTSC. “Now we’re fighting the DTSC and Exide. In our eyes, they’re co-conspirators,” Gonzalez says.

The Poison Paper Trail and Complacency

Exide, and their predecessor, National Lead, had a long history of poisoning the surrounding communities. In 1972 Dr. James Dahlgren, a physician at the UCLA Health Center’s Infectious Diseases department focusing on workplace toxins, was approached by a worker at the then-National Lead battery recycling plant in Vernon. The man complained of chest pains, infertility, and said that a coworker at the plant had recently taken ill and slipped into a coma.

Dahlgren treated the patient, and a number of his coworkers, and got a few of them disability insurance by proving that their illnesses were caused by the lead and arsenic toxins from their work at the plant. He was able to get the newly created OSHA, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, to inspect the facility in Vernon and impose some worker safety protocols, but that was it.

“Of course,” Dr. Dahlgren says when I ask if he had any idea at the time that the facility might have been poisoning the communities nearby, “I made that point then. We made the point that the neighborhood was probably being poisoned, but we couldn’t get any money to do any studies of it.”

“Nobody should be living in any of the areas contaminated.”

According to records since released, multiple state agencies were well aware of the lead poisoning issues at the facility. From 1987 to 2014 the California Department of Public Health was aware of 2,300 blood test from workers showing lead levels well above normal. DTSC had also performed ten enforcement actions against the company and cited more than 100 violations of California’s hazardous waste laws, but it wasn’t until the community protests in 2007 that Gonzalez participated in that AQMD, the state’s air pollution regulatory agency, started an investigation. In 2013 AQMD finally released a study saying that 250,000 people, and 10,000 homes were in danger of chronic health consequences from lead and arsenic being spewed out of the facility, with 2,500 homes in a 1.7-mile radius of the facility listed as “priority” cleanups.

“That was the point where I lost all trust in DTSC,” Gonzalez says, “They knew how bad it was, they knew how bad the air was, and nothing happened for so long.”

At a community meeting at Resurrection Church on March 2019, Dr. Dahlgren referred to the ongoing lead contamination of people in southeast L.A. as a “Chernobyl-level event,” referring to the 1986 nuclear reactor implosion in Soviet Ukraine, that caused widespread radiation poisoning, forcing residents of cities nearby the facility to abandon their homes and whole cities for good. “Nobody should be living in any of the areas contaminated,” Dahlgren went on to say.

Exide has fought the lawsuit, and has constantly denied their own responsibility for the lead contamination crisis, pointing to widespread contamination from lead paint in the area as the true cause of the issue.

As a part of Exide’s settlement with the Attorney General the company agreed to pay $9 million upfront for cleanup efforts, and an additional $5 million in three installments from 2018 to 2020. At the same time, Exide filed for bankruptcy protection in the state of Delaware to protect against having to further fund cleanup efforts. Since then the varying state and local agencies have been scrambling for cash for cleanup efforts. In 2016 former Governor Jerry Brown appropriated $176.6 million to the DTSC in the form of a loan, with the hope that one day an AQMD lawsuit against Exide would recuperate the cost to the state, and taxpayers, of the cleanup, which DTSC estimates costs $60,000 per house, again, for over 10,000 homes.

Exide has fought the lawsuit and has constantly denied their own responsibility for the lead contamination crisis, pointing to widespread contamination from lead paint in the area as the true cause of the issue. State tests found that thousands of homes were also contaminated with lead-based paint, some of them the same homes that have contaminated soil caused by Exide. One of the major brands of lead-based paint was Dutch Boy, which was manufactured by National Lead, the company that owned the battery recycling facility in Vernon before Exide. Soil sampling finding antimony in residences around the Exide facility, a metal that’s used in lead batteries, points towards Exide though.

A bill now circulating through the California State Assembly proposed by Assemblymember Miguel Santiago of District 53, a district that includes Vernon, Huntington Park and Boyle Heights, would send another $100 million to the DTSC as a loan to finance cleanup efforts. A state senate analysis found that the interest payments on Brown’s aforementioned loan have already totaled up to $56.4 million since 2017.

Assemblymember Cristina Garcia of District 58, which includes Commerce, has also fought for a couple of years now to get the state to put a tax on both battery recycling manufacturers, sellers, and buyers, with an estimated revenue of $32 million going towards the Exide cleanup process.

“How far will that go?” says Mark Lopez, the executive director of East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, an environmental justice activist group located in Commerce and Long Beach that fought to close the Exide facility.

“The trust isn’t there,” Lopez goes on to say. “DTSC is the primary driver for this whole process, and they’ve been driving off the road, or even in the wrong direction.”

Alatorre said she had no idea about the lead contamination in the area until a friend invited her to a community meeting at Resurrection Church. After the meeting, she made an immediate connection to the effects of lead poisoning to her family’s history of health problems, including a grandfather with diabetes, a younger sister who developed brain tumors, and her own son who developed anemia after moving into the contamination zone.

Lopez, Gonzalez, and other residents of the area interviewed for this article consistently complained of slow, haphazard, and generally poor communication, between the DTSC and the communities affected by lead contamination, in both hearing community and residents’ concerns and ideas, and the department communicating their plans for the cleanup.

Nora Alatorre moved out of her home in La Puente and moved into the house her grandparents had lived in and raised their children, her mother, in, on the border of East L.A. and Boyle Heights in 2016. Alatorre said she had no idea about the lead contamination in the area until a friend invited her to a community meeting at Resurrection Church. After the meeting, she made an immediate connection to the effects of lead poisoning to her family’s history of health problems, including a grandfather with diabetes, a younger sister who developed brain tumors, and her own son who developed anemia after moving into the contamination zone.

“I actually had to contact the DTSC myself,” Alatorre says about having her soil tested for lead, in the late summer of 2016. “Then they came out to sample my soil, then a year went by, and then they sent me a packet, which took me a while to decipher. It said that I had lead in my soil. Then it took them another year to actually come out and clean my soil in 2018, the week after Thanksgiving.”

Having heard of shoddy cleanup work by the DTSC at other homes in the area by contract workers hired by the department, she took photos and supervised their work as much as she could during the two week cleanup of her house.

“I bugged the heck out of them,” Alatorre says, “They didn’t put down tarps they were supposed to put down, they didn’t put a sign on the fence warning people that it’s contaminated. They also just covered the contaminated dirt with new dirt. Some of the contract workers didn’t have face masks on. Were they not informed that they were cleaning up toxic soil?”

DTSC sent L.A. Taco a dead link to a webpage in response to questions about residents negative experiences with the cleanup process.

Asked if she feels safe now that the cleanup is over Alatorre says, “Not really. A lot of the other properties on my block haven’t been cleaned, and it’s not going to be clean unless every property is cleaned.”

Exide wasn’t the last lead polluter in L.A. About 15 miles to the east of the former Exide site in the City of Industry in the San Gabriel Valley lies Quemetco, the last lead battery recycling plant west of the Rocky Mountains.

The home behind Terry Gonzalez’ home was cleaned awhile ago, but Gonzalez’ home has not. The soil in her home was tested and found not to exceed the levels that would put her in the priority cleanup group.

“They’ll pick one home in the middle of the block to clean up, but then the rest of the homes won’t be remediated at all. And guess what happens when time goes by and wind comes along? It blows that dust into other homes.” Dr. Dahlgren says, “They’ve got to do the entire block. Every one of these homes has lead levels above safe levels.”

“They’ve frustrated the community so much that they’ve stopped caring,” says Gonzalez about the DTSC, “and it worked. A lot of us gave up. We’ve been so battered and mistreated by the DTSC.”

“There’s still anger in the community,” Lopez says, “We wish we could just focus on Exide, but we can’t. There are so many other issues in our community.”

“What was Exide’s business now comes here.”

Among the many environmental justice issues EYCEJ works on, including continuing to advocate for the Exide cleanup, is organizing around opposing the expansion of the 710 freeway, creating green zones in the city of Commerce, advocating for traffic and walkability measures in East L.A., and advocating against the construction of a new railroad system for transporting goods from the Port of L.A. in Long Beach.

“These fights have been happening simultaneously,” Lopez says.

Exide wasn’t the last lead polluter in L.A. About 15 miles to the east of the former Exide site in the City of Industry in the San Gabriel Valley lies Quemetco, the last lead battery recycling plant west of the Rocky Mountains.

“What was Exide’s business now comes here,” says Rebecca Overmyer-Velazquez of the Clean Air Coalition of North Whittier and Avocado Heights, a local environmental justice coalition that has fought both Quemetco and the DTSC to better monitor the facility, and to accurately and efficiently study the effects of the facility’s operations on the surrounding communities of Hacienda Heights, Avocado Heights, and La Puente.

The DTSC has directed Quemetco to test blood samples and do a soil test in residential areas in a 1.6-mile radius from the facility, but as of 2016, the company has only tested a third of the residents around the facility. In October of last year, the California Attorney General sued Quemetco, alleging the company broke 29 state laws, including failing to stop hazardous waste from coming into surrounding residential neighborhoods, and an underground aquifer in the area.

Gonzalez would like to see Boyle Heights, and the rest of southeast L.A. be declared a national state of emergency and have either the EPA or the Army Corps of Engineers takeover the cleanup efforts.

“The City of Industry is like Vernon, but with better political connections,” Overmyer-Velazquez says, “We’re so done with the DTSC. It’s like who’s side are you on?”

In a lengthy report from 2013 titled Golden Wasteland: Regulating Toxics, or Toxic Regulation? about the DTSC’s failure to stop, or mitigate the worst effects of toxic polluting businesses around the state by Consumer Watchdog writer Liza Tucker writes, “DTSC’s bureaucratic culture is timid and risk-averse, and its officials hide behind a weak and fractured system of environmental regulation and enforcement. The DTSC either does not fully understand its own powers or intentionally refuses to apply them. DTSC relies on out-of-court settlements, levying wrist-slap fines, instead of suspending the permits of serial violators of environmental laws.”

Overmyer-Velazquez would like to see the DTSC reorganized and run by scientists that study toxicology, “and not bureaucrats like now.”

Lopez would like to see a local agency, “not in Sacramento,” takeover the Exide cleanup efforts. Dahlgren would like to see the DTSC be completely restructured, and for a new department to be created in its wake.

Gonzalez would like to see Boyle Heights, and the rest of southeast L.A. be declared a national state of emergency and have either the EPA or the Army Corps of Engineers take over the cleanup efforts.

Alatorre just wants the DTSC to listen to the communities it interacts with. “What if they just really listened to the community’s ideas to find a solution and not just look at everything as a problem? Because it’s never going to be fixed without doing that.”

--

L.A. Taco has received the following comment from the Department of Toxic Substances Control and California Environmental Protection Agency:

The Department of Toxic Substances Control has issued the following statement in response to Assemblymember Santiago’s approved Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request on the Exide Cleanup Project.

“The Department of Toxic Substances Control welcomes every opportunity for transparency in the Exide cleanup, the largest residential cleanup of its type in state history.

“We understand the impacts to the community and have a dedicated team working daily in the neighborhoods surrounding the former Exide facility. DTSC staff members make hundreds of in-person interactions and phone calls with residents each day. Through Feb. 21, DTSC has overseen the cleanup of 1,676 parcels, and with 33 crews in the field is cleaning up about 100 properties per month.

“DTSC respects the critical nature of this project and the need to maximize resources to expedite clean-up efforts. We have secured the expertise of a project management consultant to ensure we appropriately track and control contract costs. We have also initiated several third-party audits of our work, all of which have resulted in positive reviews. Our top priority is protecting the health and safety of people in this community.”

The Department of Toxic Substances Control has issued the following statement in response to Assemblymember Santiago’s approved Joint Legislative Audit Committee audit request on the Exide Cleanup Project.

“The Department of Toxic Substances Control welcomes every opportunity for transparency in the Exide cleanup, the largest residential cleanup of its type in state history.

“We understand the impacts to the community and have a dedicated team working daily in the neighborhoods surrounding the former Exide facility. DTSC staff members make hundreds of in-person interactions and phone calls with residents each day. Through Feb. 21, DTSC has overseen the cleanup of 1,676 parcels, and with 33 crews in the field is cleaning up about 100 properties per month.

“DTSC respects the critical nature of this project and the need to maximize resources to expedite clean-up efforts. We have secured the expertise of a project management consultant to ensure we appropriately track and control contract costs. We have also initiated several third-party audits of our work, all of which have resulted in positive reviews. Our top priority is protecting the health and safety of people in this community.”