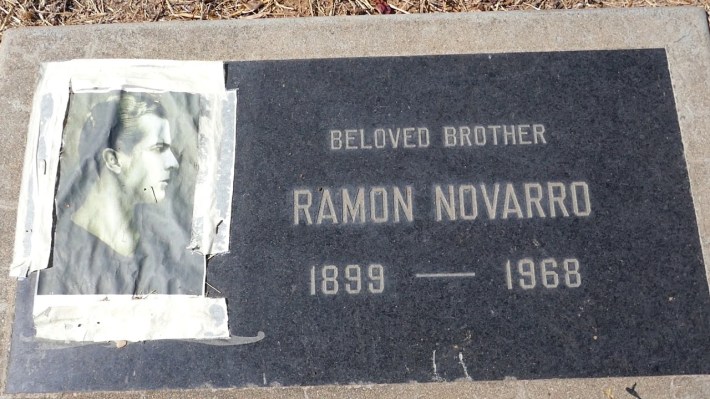

You can still hear the chariots if you stand in the right place at Calvary Cemetery, where the hum of L.A. traffic supplies the musical score for a silent film star’s final resting place.

A moment later, the nearby rumble of the never-truly-complete 710 freeway and the constant motion of Whittier Boulevard transforms into the beating hoofs of galloping horses. And boom—

Jump cut—1925. Ramón Novarro races a team of horses through a roaring arena. Dust explodes behind him like fireworks. He’s bronze-skinned, soaking in the Roman sun—then the director yells, “Cut, we got it.”

Novarro, the Mexican American star of the silent-era epic "Ben-Hur," smiles divinely at the camera, fully aware he’s about to become Hollywood’s crown prince. His family’s journey—fleeing the violence of the Mexican Revolution from Durango to Los Angeles— and their sacrifices feel worth it.

Jump cut—1930. Three years after the success of the "The Jazz Singer" decimated the golden age of silent film, Novarro walks alone down Sunset Boulevard, the city that loved him already forgetting his name. The talkies have come, and his accent is now a liability. The papers that once praised his “noble features” start whispering about his male lovers.

No matter. Novarro was smart with his money. He doesn't need to be a star to live a good life—as good as possible for a gay man fighting against his own devout religious beliefs.

Jump cut—1968. Silver Lake. A bungalow full of Art Deco mirrors and Catholic icons. Two men, posing as escorts, ring the doorbell. They’re crooks. Two brothers who mistakenly believe Novarro has cash stuffed under a mattress somewhere. He doesn’t. Too smart for that. They torture him anyway, beating him until his conflicted Catholic soul leaves his lifeless body.

Jump cut—present day. East Los Angeles. Calvary Cemetery. A flat gray marker etched with “Ramón Samaniego Novarro 1899 – 1968.” The sky darkens as somewhere nearby, a family lights candles for Día de Muertos in a city that forgets and remembers at the same time.

If you stand there long enough, and look around this corner of East Los, you can feel all of it—the fame, the loneliness, the faith, the reinvention, the whole myth of Los Angeles, resting quietly in the dirt of six closely clustered cemeteries that tell the story of the City of Angels.

Remembering the Dead

In many ways, celebrating Día de Muertos is celebrating Los Angeles distilled: A mix of Indigenous belief, Spanish Catholic ritual, immigrant nostalgia, and Hollywood-fueled lore.

But the tradition predates Hollywood, predates California itself. For the Mexica and other Indigenous peoples of central and southern Mexico, death was not an ending but a continuation—another step on a circular path that always led back home.

Here in the L.A. Basin, its original people—the Tongva, Chumash, and other Natives—held a similar view: that ancestors lived in the land, the rivers, the wind.

Then came the Spanish, who saw permanence in death. They built missions—San Gabriel, San Fernando, San Juan Capistrano—each with a walled cemetery beside the chapel. Crosses replaced shell beads; Latin prayers replaced songs. Death became a way to claim both souls and expand territory.

After Mexico gained independence in 1821, those mission cemeteries still anchored communities, but new pueblos grew around them, including the one they called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula. For a brief moment, Indigenous converts, Spanish settlers, mestizos, and soldiers shared the same soil. The city’s dead reflected its living diversity—before segregation arrived with statehood.

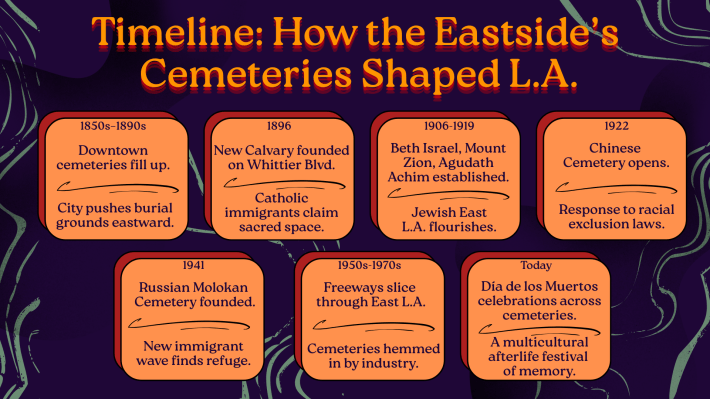

When the United States seized California in 1848, cemeteries became a matter of property. Anglo Protestants built theirs near Downtown; Catholics and non-whites were pushed to the margins. By the late 1800s, as the modern city rose, the old graves near what’s now Chinatown were declared unsanitary. The bones of early settlers, Native converts, and Mexican families were dug up and reburied east of the river.

Los Angeles, a city built on reinvention, decided even its dead had to move for progress.

That’s how the Eastside became the city’s afterlife district—the one place that could hold everyone that history forgot. Catholics at Calvary. Jews along Downey Road. The Chinese and the Russians a few blocks away. Each community carved out its own corner of eternity, separated by fences but united by geography and need.

The result: a dense cluster of cemeteries that tell the real story of Los Angeles—faith, segregation, migration, and survival, all side by side.

Six Eastside Cemeteries That Show L.A.’s Evolution

Calvary Cemetery and Mortuary (1896) ~ East L.A.

When the original Calvary, near present-day Chinatown, filled up, the Archdiocese bought 137 acres off Whittier Boulevard. “New Calvary” became the final stop for generations of Mexican-American families, priests, and nuns—and stars like Novarro. The marble mausoleums and Virgin statues show how Catholicism anchored immigrant life here, giving dignity to people who built the city’s foundations but rarely its headlines.

Beth Israel Cemetery (1906) ~ Boyle Heights

Created by Congregation Beth Israel, it served the early Orthodox Jews of Boyle Heights. These were pickle sellers, tailors, and teachers—people who turned an immigrant ghetto into a cultural hub. When their grandchildren moved west to Fairfax, the cemetery stayed behind, the stones inscribed in Hebrew and Yiddish telling a story of migration and memory.

Agudath Achim Cemetery (1919) ~ Boyle Heights

Founded by the Agudath Achim congregation, it sits right next to Beth Israel. Its modest headstones reflect a working-class piety—the Eastside Jews who couldn’t afford the ornate monuments of Hollywood Forever but built synagogues, bakeries, and schools that shaped early L.A.

Mount Zion Cemetery (1916) ~ East L.A.

Operated by a chevra kadisha (burial society), Mount Zion provided free plots for those who died without means—a physical testament to Jewish mutual aid. It’s the humblest of the Downey Road trio but maybe the most spiritual: An eternal safety net for the forgotten.

Chinese Cemetery of Los Angeles (1922) ~ East L.A.

Because Chinese Angelenos were barred from most burial grounds, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association purchased land on the city’s edge. Traditional altars, incense burners, and bright red gates mark the space. Today it sits boxed in by the 60 and 710 freeways—a literal embodiment of how infrastructure buried entire communities while they were just trying to exist.

Russian Molokan Cemetery (1941)

The Molokans—pacifist Christians exiled from Russia—settled on the border of East L.A. and Commerce. Their 14-acre cemetery, with hand-painted icons and white wooden crosses, tells a parallel immigrant story: Outsiders building their own sanctuaries in a city that barely knew their names. Now surrounded by warehouses, it’s a pocket of stillness amid industrial sprawl.

The Living

These resting grounds are a reminder that Día de Muertos isn’t just Mexican. It has become a Los Angeles holiday, an adopted ritual of remembrance that bridges everyone buried here.

Walk these grounds long enough and you can trace the entire migration history of Los Angeles in headstones and iconography. The Spanish and Mexican names at Calvary mark the city’s colonial and revolutionary eras. The Irish and Italian Catholics who followed represent the early waves of European immigration. The Jewish cemeteries on Downey Road tell the story of Eastern Europeans who fled pogroms to find freedom on the West Coast, while the Chinese Cemetery testifies to those who built the railroads and laundries yet were banned from owning land or buying burial plots elsewhere. The Russian Molokan Cemetery speaks to a sect of pacifists who escaped Tsarist persecution only to build quiet lives amid L.A.’s factories.

Together, they form a map of displacement and resilience—a story of how the world came here and then stayed.

Ramón Novarro never got his Hollywood ending. But maybe he got something truer: A role in the eternal ensemble cast of Los Angeles.