This article was originally published in 2020.

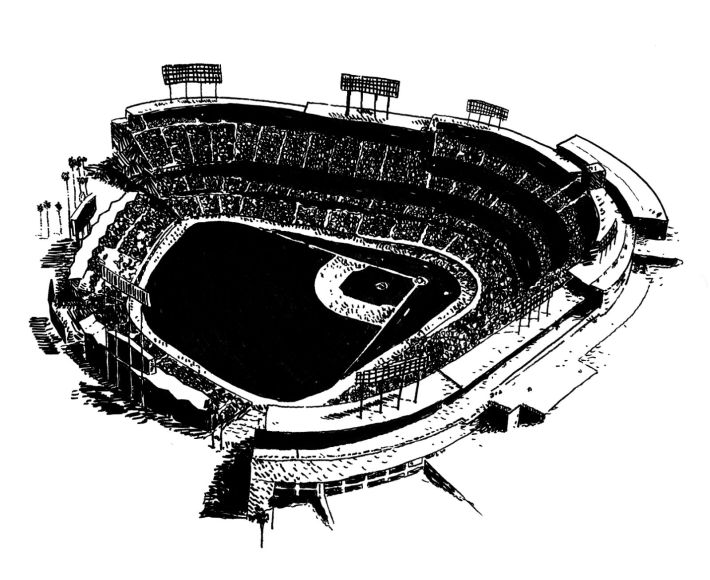

It’s October in Los Angeles. The Dodgers’ hope to advance to the World Series is at an all-time high after another record-shattering season, and Dodger Stadium is a ghost town.

There are no fans in crisp Dodger Blue, no tailgate parties, front-lawn carne asadas, or pre-game drinks at the Shortstop before the long hike up with your Blue Crew to your upper reserve seats under gorgeous views of Vin Scully’s “cotton-candy skies” touching purple San Gabriel Mountains against the downtown skyline. No green grass, Tommy Lasorda, and Magic Johnson sightings, or ear candy from Dodger Stadium organist Dieter Ruehle.

Instead, the perennial Western Division champion Los Angeles Dodgers had to suit up in their white uniforms to play in their eighth consecutive postseason “home opener” not in Walter O’Malley’s baseball cathedral carved into Chavez Ravine, but at a neutral site, a sterile bat cave of a ballpark with a boring corporate name in Arlington, Texas.

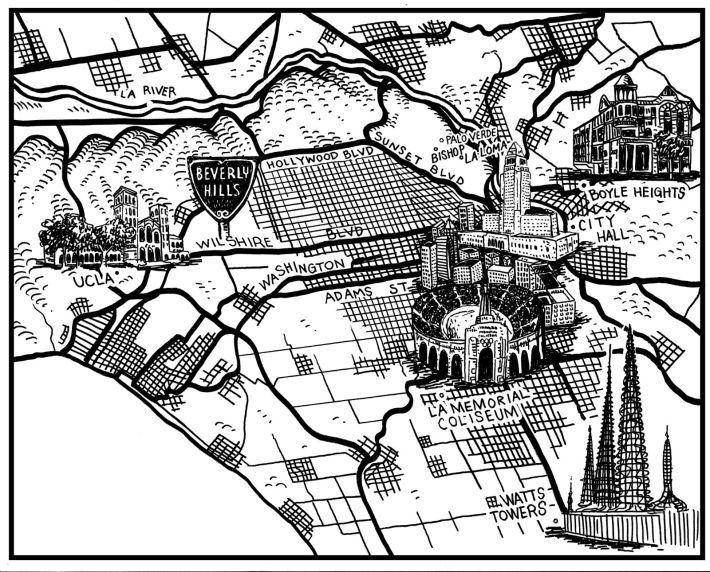

For now, the ghosts of the Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop barrios have the place back to themselves again, a reminder of Frank Wilkinson’s haunting words to a high school history class in Culver City in the early 2000s:

“Dodger Stadium should not exist.”

These may be blasphemous words to true-blue L.A. Dodger fans, former players, and anyone who has made Dodger Stadium a spiritual seasonal home for baseball every April through October as they have since 1962.

But Wilkinson’s words also speak an inconvenient truth at the core of a book about building Dodger Stadium and what it means for outsiders to claim “home” in a place that only exists because longtime residents of three whole neighborhoods lost theirs.

Eric Nusbaum’s book, Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between (Public Affairs, 2020), takes Dodger fans and anyone else interested in baseball and L.A. history beyond the well-documented events of the Dodgers’ arrival and the building of their new stadium. By focusing on three central stories—the Aréchiga family, Frank Wilkinson, and the civic desire for big-league baseball in post-WWII Los Angeles—Stealing Home adds a fresh perspective to the tale Dodger fans think they already know.

A Pre-History to the Official History

Sixty-eight years ago on October 8th and 9th, in 1959, the Los Angeles City Council sold the ‘vacant’ land a mile north of City Hall to Walter O’Malley to build a new home for his Dodgers. Stealing Home reads like a pre-history of this moment, a pre-history of Dodger Stadium. It details the political movidas, unassuming activists, and everyday events spanning two countries and several decades that created the ripe conditions for O’Malley to buy cheap land from the city, move his Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles, and build his team a brand-new ballpark.

Nusbaum follows the people on the ground and behind the scenes rather than the ‘movers and shakers’ at the top like the Chandlers and O’Malleys, whose perspectives and grand purposes are too often privileged in the telling of this complex story of how Dodger Stadium came to be.

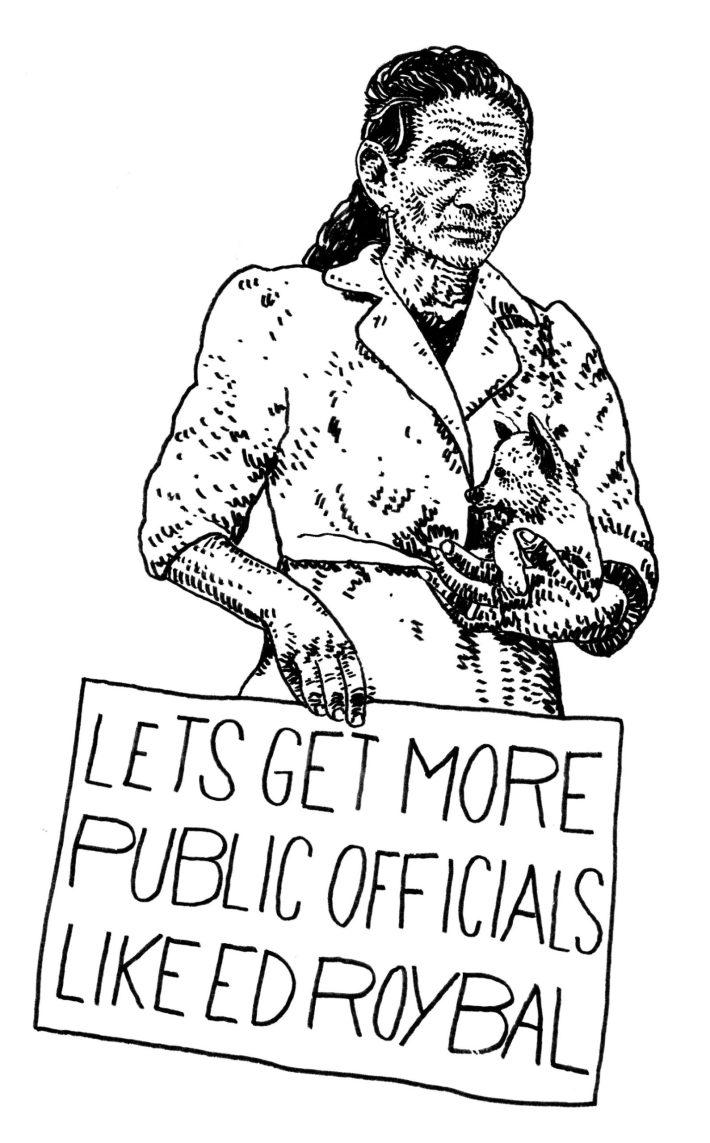

In centering the story of Zacatecas-born Abrana Cabral (later Aréchiga) and her family, as well as Frank Wilkinson and his family, Nusbaum helps us get to know the people behind the enraging eviction images not just as victims, but as active resistors of civic injustice driven by developers’ greedy land interests. We learn how their lives intersect with those in power, politicians like Ed Roybal, Kenneth Hahn, and puppet mayor Norris Poulson.

Nusbaum reminds readers that the City of Los Angeles, not the Brooklyn Dodgers, are the ones who “kicked out the Mexicans” on Tongva land.

We also learn about some of the Dodger greats before they ever pulled on the uniform, like Compton’s Duke Snider and Roosevelt High’s Willie Davis, a product of the very L.A. public housing projects that men like Frank Wilkinson advocated for the whole city. Their lives are also among those “caught in-between” the civic government machines, private business, and baseball’s expansion west of the Mississippi River.

Strength in Storytelling

The strength of Stealing Home lies in Nusbaum’s storytelling voice. Though the book is nearly 300 pages long, the short chapters and fascinating side stories make an enjoyable page-turning read. The writer and former editor at Vice was born and raised in Los Angeles on Dodger baseball. As such, Nusbaum deftly balances holding space for deep Dodger fandom along with a subtle critique of the processes that brought the team here.

Simultaneously, the exquisite details and forays into fascinating tales about the likes of General Santa Anna and Mexican baseball empresario Jorge Pasquel can feel distracting at times. Still, Nusbaum manages to keep his three through-lines front and center—the Aréchigas, the Wilkinsons, and L. A.’s civic desire for big-league baseball status—ultimately lending cohesiveness to the book that carries readers to a satisfactory ending.

In Stealing Home, Nusbaum also creates room for reconciliation—for the families and descendants of the Aréchigas and other families of Palo Verde, Bishop, and La Loma; for the City of Los Angeles and the L.A. Dodgers organization; and for the true-blue fans who aren’t afraid to dig a little deeper into the reasons why we call Dodger Stadium “Chavez Ravine.”

Those of us who care about Los Angeles and the love the Dodgers should learn the “uncomfortable history” of the beloved stadium occupied by our home team for three reasons: “It prepares us to deal with the present, we’re still living it, and it wasn’t that long ago.”

“On some level,” writes Nusbaum in the Preface, “I have wanted to write this book since the day I saw Frank Wilkinson in high school. The story broke my heart.”

These heartbreaking stories comprise what L.A. Times columnist Gustavo Arellano described as the “uncomfortable histories” of places we know and love but may not know so much about. As Nusbaum told Arellano in a webinar conversation about Stealing Home, those of us who care about Los Angeles and the love the Dodgers should learn the “uncomfortable history” of the beloved stadium occupied by our home team for three reasons: “It prepares us to deal with the present, we’re still living it, and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Yes, the book is about baseball, Los Angeles, and the lives of people like Abrana and Manuel Aréchiga and Frank Wilkinson. The book honors those lives touched by the Dodgers and city drama around whether Elysian Park would be a home for low-income residents or a big-league baseball team from Brooklyn. It’s also about McCarthy’s red-baiting culture of the United States in the 1950s and how baseball was used as a tool to weed out communists—like when Jackie Robinson had to testify against Paul Robeson at a HUAC hearing. It’s about the contradictions of progressive politics proffered by white people like Wilkinson and Roz Wyman regarding Mexican immigrant lives and the ruthless politics of city elites to secure private investment and national status over the stability and dignity of its most vulnerable residents.

In the end, Stealing Home is about land—it’s always about land, access, and the deals that orchestrate the destruction of neighborhoods for “eminent domain.” About who gets to stay and who gets forced off their land; about who steals and whose homes are stolen. Spotlighting these stories means that Stealing Home also complicates another common narrative about “how the Dodgers kicked the Mexicans out of their homes to build their stadium.” Nusbaum reminds readers that the City of Los Angeles, not the Brooklyn Dodgers, are the ones who “kicked out the Mexicans” on Tongva land. And in the end, O’Malley brought his team to L.A. because, as it turns out, the city’s Mexicans and African Americans overwhelmingly voted yes on “Proposition B for Baseball” in 1957.

Adds to the Archive

I’d never heard of Proposition B, never learned that a lot of Mexicans and African Americans voted to bring Brooklyn’s Dodgers to L.A. Not all Mexicans in L.A. were anti-Dodgers, like my mom’s father, who vowed never to cheer for a team who could do that to hardworking Mexican immigrants like him.

But this is why I enjoyed Stealing Home. It contributes to the respectable archive of scholarly work, documentary films, stage productions, and musical tributes that tell the full story of Dodger Stadium, not merely a sanitized official league team version of it. And it brings to life the voices we rarely get to hear that fill in the blanks of what we think we know about the ballpark in Chavez Ravine.

It’s October in Los Angeles. The Dodgers are down 2 - 1 against Braves in the National League Championship Series in their eighth-in-a-row search of the elusive World Series title.

And Dodger Stadium is empty.

There are no fans, no parties, no blue heaven. Just the cruel irony of the Dodgers playing postseason “home games” away from home, as if Dodger Stadium doesn’t exist.

Maybe now, 68 years later, the ghosts of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop finally have some peace.

Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between is out now.