[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap]t’s a scorching hot, dry summer day in South Gate and the Los Angeles River is roaring with the kind of exuberant music-making perhaps not seen since the Tongva built life along the L.A. basin. More than 5,000 people are in attendance at the “first annual” SELA Art Festival to witness the likes of Buyepongo, Quetzal, The Altons, Culture Clash, and Weapons of Mass Creation.

People from all over Los Angeles endured traffic on the 710 to witness the collection of Chicano performers, browse the vendors displaying skincare products sourced from mercados in Mexico, Instagram clothing brands with embroidered phrases like “sin miedo” and “chingona,” shop for bilingual children’s books about Selena and Cantinflas, and of course, eat tamales, tacos, and tortas.

On this July day, the river, once a source of fertile sustenance, is the setting of a mini revival of cultural and literal nourishment for Southeast Los Angeles. But can life along the paved arroyo endure?

The state’s most powerful legislator is really hoping so.

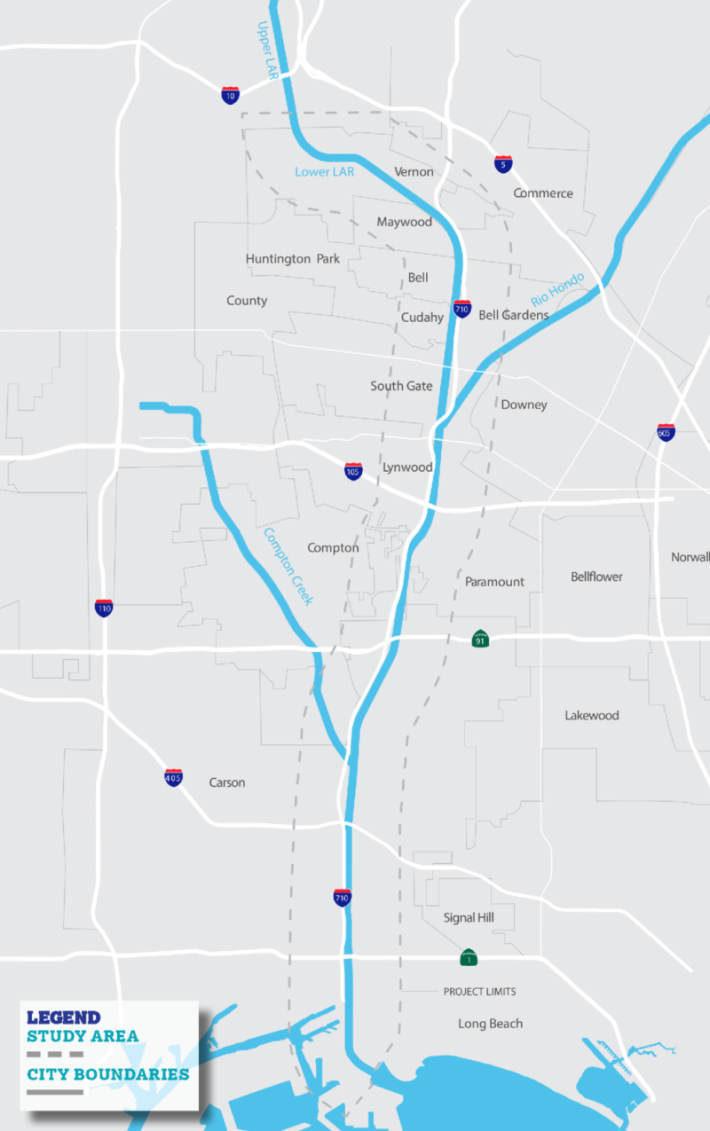

Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon, D-Lakewood, who sponsored the festival, is pushing lawmakers in Sacramento to fund a complete revitalization of the L.A. River from the edge of downtown to Long Beach. While state and local leaders have long touted the area of the river that has been already re-greened — especially along Atwater Village, Elysian Valley, and the Griffith Park area — much of the rest of the concrete waterway is neglected as it courses south toward the L.A. ports.

Los Angeles County adopted a master revitalization plan for the entire Los Angeles River in 1996. According to Rendon, after two decades of building and projects in the north, the south deserves some revitalization.

“All the kayaking opportunities, the recreational opportunities, are in the northern part of the river. And from that vantage point, it’s a stark distinction between what’s happening in the upper river, and what hasn't happened in the lower river.”

Rendon recently spoke with L.A. Taco about his plans to revitalize 19 miles along the lower region of the Los Angeles River and build a giant outdoor destination for festivals, concerts, and recreation. Rendon's bill, AB 530, addresses the corridor within one mile of either side of the river from the city of Vernon to Long Beach. And this art fest on the river, Rendon believes, revealed not only the vibrancy of the community there, but that “people from outside of Southeast L.A. are willing to come into the district to see what we have to offer.”

[dropcap size=big]B[/dropcap]ut “restoration” and “enhancement” is often a preface to gentrification. This newness on the horizon for SELA could mean higher rents and ultimately displacement for residents, as seen along the one stretch of the river that has been revitalized. Lynwood could easily become Echo Park: six-dollar coffee shops, overpriced sandwich eateries, and thrift shops that are anything but thrifty.

Anti-displacement was the number one policy issue for the entire community,

Rendon’s office claims to be prepared to combat gentrification before it happens. According to Raul Alvarez, senior advisor for the speaker, the surrounding cities are known to be “dense” and “hardcore.” There are approximately 2,500 homeless people living along the river’s corridor. And 64% of households within a mile of the corridor are considered low income. Eighty percent of the businesses near the corridor are considered “small,” and 72% of these businesses are minority-owned.

Though Alvarez pointed out that a sense of community is still very much prevalent, as seen at the festival, opportunities and proper settings for such events have been scarce until very recently. “Anti-displacement was the number one policy issue for the entire community,” Alvarez told L.A. Taco.

So the speaker's office created an Anti-Displacement Toolkit that informs residents about displacement issues, developing policies, and inclusionary housing. His office is also in ongoing meetings with each city’s council and senior staff to address how each city can combat displacement.

Rendon sees a distinction between developing what the community has to offer and replacing it with outside corporate interests. His project, he said, was born out of trips back home from Sacramento every Thursday when he would catch a view of the city from the plane as it flew south past downtown.

“I realized there was no development,” he explained.

RELATED: Apple to Open Store in Historic Broadway Theater

[dropcap size=big]I[/dropcap] n 2014, voters approved a water bond that included $100 million for the river. In 2015, Rendon’s bill for the project was signed into law by Gov. Jerry Brown. And this June, Long Beach was the first city in the region to get a piece of the new river, the Deforest Park Wetlands Project.

Currently, the river has mild recreational uses, such as the 8.7 miles of multi-use bike and walking trails along the river’s corridor. But entrances to these trials are incognito and uninviting. Additionally, although the wide river channel protects communities from flooding during the rare rainy season, the water is not multi-functional for the benefit of local greenery.

Along with the 19 miles in length the plan aims toward, the actual channel is an extraordinary 400 feet wide in most places. The plan hopes to make use of this space by diverting the water on rainy days outside the channel.

The inspiration for this came from engineering the Netherlands applies to its dealings with waters. The country sits at the mouth of three major rivers and much of its land lies below sea level, but the Dutch have learned to plan for flooding in multifunctional ways.

RELATED: Misconduct Claims Leave Big Chunks of L.A. County Without Representation

[dropcap size=big]R[/dropcap]endon still has a long haul to achieve this goal of development without displacement, and it’s going to involve a lot more input from the people living in the region. A community meeting regarding the LA River Master Plan is scheduled for Aug. 22 in the city of Cudahy.

The art fest came from Rendon's office, but its success would have been impossible without the help of local artists. Eric Contreras is the creator of Alivio Open Mic, a monthly platform held at his parents' garage in the city of Bell, and one of Rendon’s allies in the community.

Alivio, which translates to “relief” in Spanish, was created by Contreras in 2012 when he realized there were few avenues for expression within Southeast Los Angeles, “Every time I had to go and enjoy art, or poetry, or I wanted to express myself, I had to extract myself from my community,” Contreras told L.A. Taco. “I felt like there was an emptiness here, a desert of spaces for art.”

Members of Rendon’s staff shared his vision with Contreras at an Alivio meet-up one Friday night in April. The information triggered Contreras and his fellow Alivio allies and prompted their artistic passion and know-how. That in turn produced the art extravaganza held last July.

The very same way Alivio offers a relief of art each month inside of a home, Contreras sees the success of SELA Art Festival on the river as a potential refreshment to the Southeast L.A. community. And as well as proof that the end of this drought of creative expression may be around the corner.

RELATED: With Seizure and a Suicide, Redevelopment Struggle Takes Ugly Turns at Ports O'Call