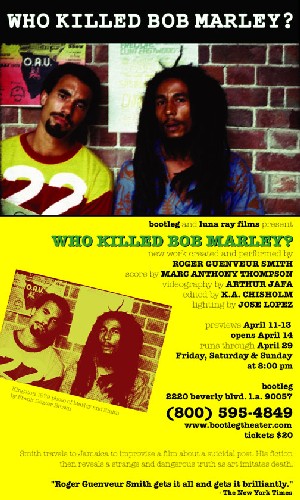

Bootleg Theater ~ 2220 Beverly Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90057 ~ (800) 595-4849 ~ Fri, Sat, & Sun. @ 8 PM ~ $20 ~ Ends April 29th

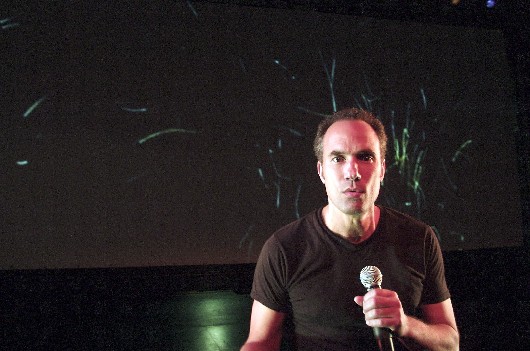

A dead man floats face down in the sea on a massive movie screen, gently rocked by Marc Anthony Thompson's unhurried and mesmerizing beat. In front of the bobbing body, in simple black pants, black tee, and bare feet, Roger Guenveur Smith (Do the Right Thing, A Huey P. Newton Story, Inside the Creole Mafia, The Watts Towers Project) sways like kelp, kept afloat by the current of his spoken-word tale full of young men leaping to their death from bridges or soaring like Icarus towards the heavens in defiance of God. "Power has its ups and downs," says the elevator man ferrying corporate giants between skyscraper floors.

Photo by Jason Adams.

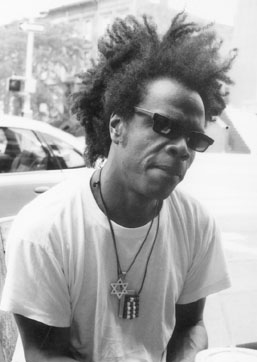

WHO KILLED BOB MARLEY?, Guenveur Smith's latest one man show, mixes urgent stream-of-conciousness flow-etry and footage of a film the actor/artist shot in Jamaica about a suicidal U.S. poet who travels to a literary festival to read his last poem, "I'm going to kill myself," with clips and stills from Smith's real-life journey as the son of "negro professionals": a father attorney and a mother dentist. Against cinematographer Arthur Jaffe's lyrical images and Thompson's pelvic thrusting riffs, Smith's powerful words ("My toes like the 10 Commandments circumventing the globe.") and Tai Chi style choreography snake-charm our hearts to get out from behind our comfort zones and be touched by Smith's lucid dreams, where Basquiat's crown is put on top of Martin Luther King's head and "this boy Cho, they could have saved him with poetry."

Inspired by Bob Marley and convinced that "All revolution is love," Smith wails, rhymes, sheds actual tears, sings like Tuff Gong himself, and explores the ups and downs of his masculine power with humility, candor and humor (imagining the casting of his own show, he puts out word for "a young Belafonte, but angrier and sweatier"). Recalling his chance meetings with the Rasta revolutionary, Smith draws together disparate places and heart-felt experience from his life and passport drawing together connections in history, words, rhythm, race, and place. Young enslaved lovers choose to jump to their death off Jamaica's Lover's Leap in the 1700's rather than be separated, while Smith's on-screen alter-ego/suicidal poet is too self-absorbed to reach the arm-length distance between him and his beautiful artist woman.

"STOP!" he urges the world around him as it forces his own feelings to spiral, and Thompson' score, like a lumbering ghost, comes to an instant halt. Recalling his days as a student of theater, dressed up as Frederick Douglass, Smith asks a bunch of young rude bwoys to turn down their dancehall during rehearsel. But he soon realizes that asking them to turn down their bass is like asking them to "turn down their race." An angry young male comes at him with a screwdriver while the crowd chants, "Yankie come fi mash up the soundsystem!" "Brother please, STOP!"

Could Smith have crossed the river to save Basquiat?

Smith wants to build a bridge between Trenchtown, Marley's teenage home, and his own streets of Baldwin Hills. Bob Marley's work, he tells us, was fueled by his search for his absent father. Playing little-big Icarus to the grandiose on-screen reflection of his own father, Smith scrutinizes and honors the man who tolerated his son's desire to be an "acteur," but was quick to remind him of the better medical or legal professions chosen by his cousins and brother.

Marc Anthony Thompson

Watching his father swimming in the Jamaican ocean he loved, Smith wonders which sins his father is trying to wash away. Was his father a "negro professional" or a "professional negro" of the "incog-negro" kind? Without conclusion, Smith still knows the sins of the father will be revisited upon the son. At a formal ceremony, while receiving an award from his peers, a grown Smith, in an uncommon gesture of reverence, hands his trophy to his father, the undeniably Black man ("he had diabetes and prostate cancer") who "got along with all the animals when he wasn't eating them."

What has this to do with who killed Bob Marley? When Roger Guenveur Smith met the Rasta Man, Marley told him "you like football, you get a team" or in his more sophisticated version from "Redemption Song": it doesn't matter whose sons we are or the fate our fathers suffered, "None but ourselves can free our minds." Reliving his encounters with Bob or the conspiracy theories he heard from people like Al Anderson, Smith stitches together portraits of bottomless Black strength, a fortitude that unfortunately comes even more attached to a life of looking over your shoulder.

Roger Guenveur Smith's seminal new one-of-a-kind-man show lives and incorporates by Marley's words, showing us what independence can do to the artist and the man even with 500 sea-urchin needles stuck in his left foot... the masculine one.