[dropcap size=big]E[/dropcap]ver since local activists protested the opening of Asher Cafe in Boyle Heights earlier this month for the gentrification it represents and the pro-Trump views of owner Asher Shalom, the restaurant has become a conservative darling. Shalom, an Israeli immigrant, has appeared on Fox News to cry victim, while other outlets have claimed with no proof whatsoever that protestors hurled anti-Semitic slurs and feces at Asher Cafe.

Some of the stories have noted that Boyle Heights used to be a heavily Jewish neighborhood before World War II. But what these reports never bother to disclose is how radical those Jews were — and how the many Jewish bakers back in the day were the most radical Jews of them all.

The full story is in the fascinating “Visions of a Jewish Future: The Jewish Bakers Union and Yiddish Culture in East Los Angeles, 1908-1942,” a 2013 dissertation by Caroline Luce, Research & Digital Projects Manager at the Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies at UCLA.

A shorter version appears in the anthology Jews in the Los Angeles Mosaic, an anthology released in 2013 by the University of California Press. Both reveal a Boyle Heights that proves the in-your-face activism of anti-gentrification groups like Defend Boyle Heights isn't a rude anomaly but rather fully in the spirit of their Jewish predecessors — and, in some way, less revolutionary.

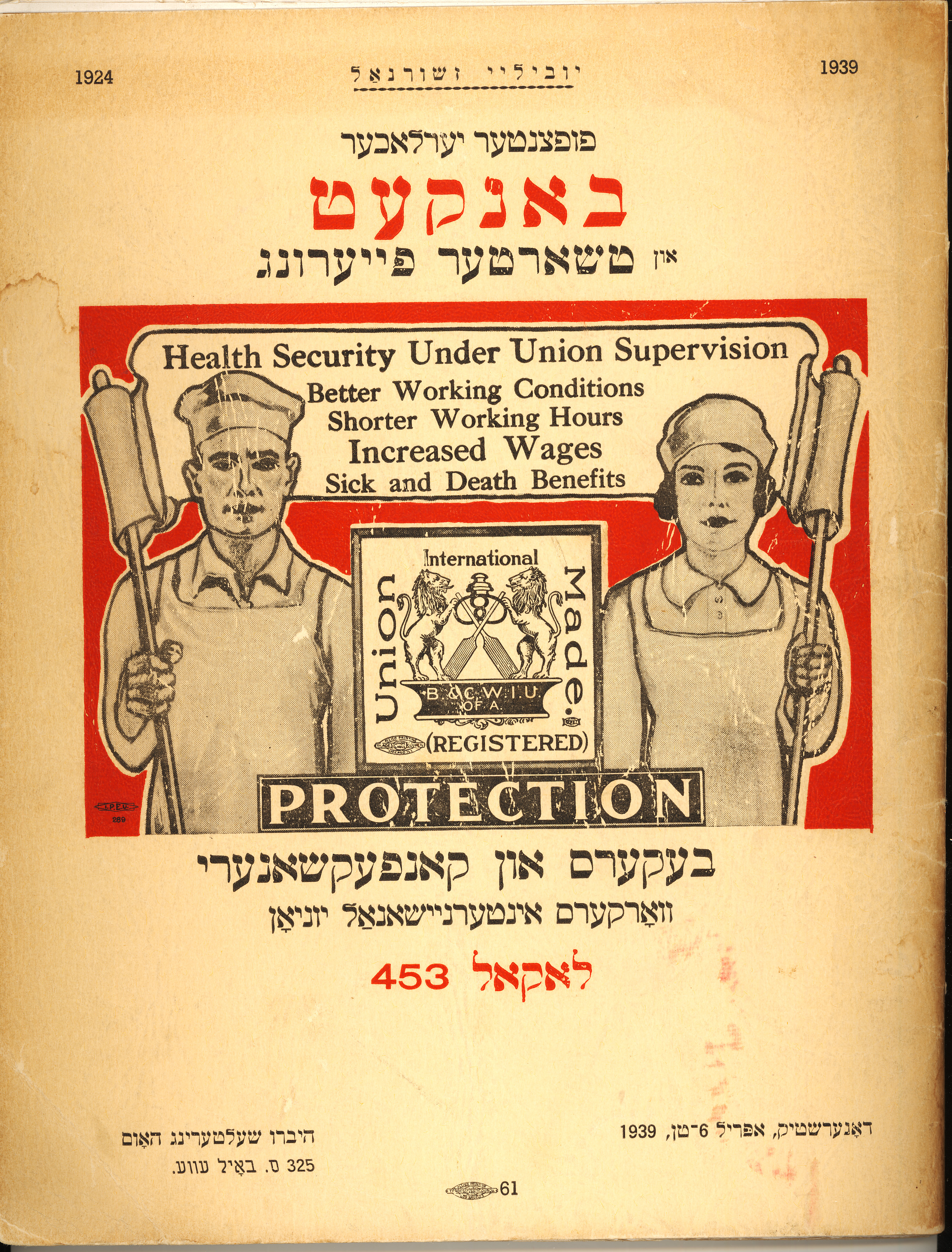

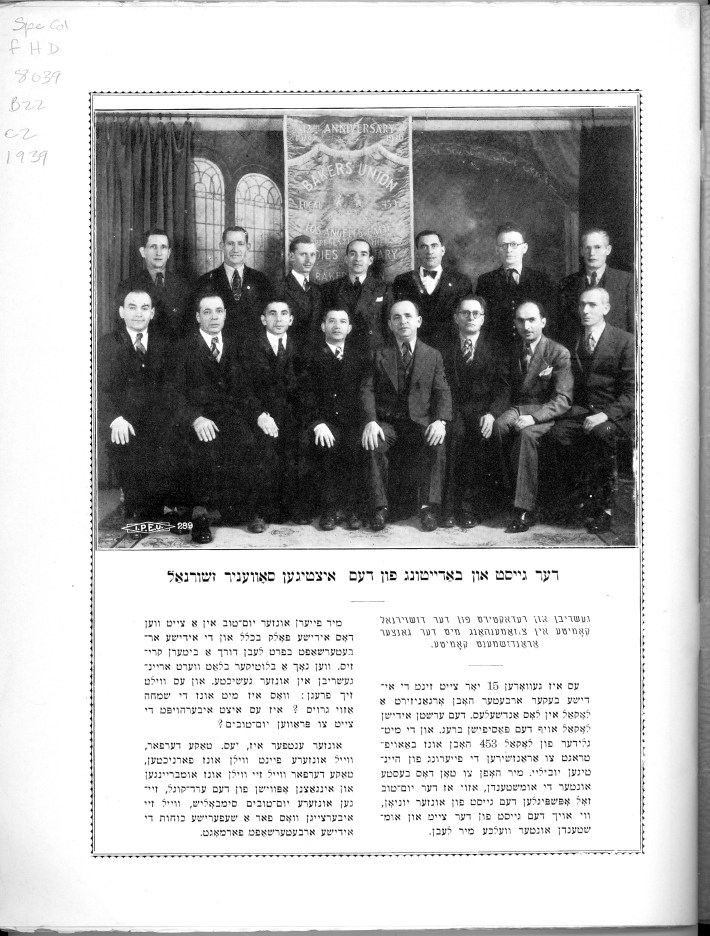

Luce focuses on Jewish Bakers Union 453 of the Bakery and Confectionery Workers International Union. They got their charter in 1924, to split from Los Angeles' main baker's union, which was overwhelmingly white and Protestant at the time. But Jewish bakers had served Boyle Heights since at least the 1910s, when thousands of refugees from Czarist pogroms made their way to the Los Angeles neighborhood; 50,000 Jews lived there by the 1930s, a time when challah and rugelech were more common in the Eastside than tacos and burritos.

Established L.A. Jews thought their newcomer brethren were “undesirable”; Yiddish-speaking socialists thought the wealthier Jews were “highly assimilated super-capitalists,” per Luce. But the rabble would make Boyle Heights the center of Jewish life in Southern California for 50 years — specifically, the bakers.

Most of them knew how to speak and read English, Luce wrote, but “they shared a commitment to preserving Yiddish language and culture as the basis of a secular, diasporic form of Jewish peoplehood and to using Yiddish an engine of community mobilization.” The bakers quickly became “the most visible and tasty part of yidishe kultur in Boyle Heights.”

RELATED: Artwashing Fight Takes Twist With Gallery's Offer to 'Ceremonially' Close in Boyle Heights

Courtesy of Carol Luce, from Dorot Jewish Division, New York Public Library

[dropcap size=big]L[/dropcap]ocal 453 created a cooperative bakery and sister cafe next door to the Cooperative Center, a radical organizing space on Brooklyn Avenue that housed the local branch of the Workers Party (both were in the building that stands on 2708 Cesar Chavez Avenue and nowadays hosts the Boyle Heights Arts Conservancy). During the Great Depression, they provided free food to Jewish community groups regardless of political affiliation and any striking Jewish unions, and organized an annual May Day celebration.

By tying their faith with their food, Local 453 made “buying union" not just a political act but a cultural one. As a Yiddish proverb that Luce happily cites said, “beser dem beker vie dem dokter” — “better to give to the baker than the doctor.”

'The contributions of the bakers and their cohorts of community activists have been overlooked by generations of historians.'

But this commitment to Yiddish culture, Luce ultimately argues, also “confined the scope of their influence.” And Local 453's progressive politics increasingly made them a target. Bakery owners created the Hebrew Masters Bakers League as an open shop, arguing Local 453 had become too radical. Bakers tried to strike in 1931 and 1932 after a successful strike in 1926, but the owners broke them both times. The Los Angeles Police Department began to regularly trash the cooperative bakery and cafe; a cafe manager even died from injuries suffered during a raid.

Local 453 fought on. They got a radio show on what's now KLAC 570 AM called “Union Label Radio Hour” and staged a strike against Heirshberg's Rye Bakery in West Adams that forced the owner to sell it to union-friendly hands. As late as 1954, Local 453 fought in contract talks to keep May Day as a day off for its members, arguing it “had been a paid holiday for 30 years,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

But eventually, the Hebrew Masters absorbed Local 453 — and the union slowly disappeared. By 2003, one of the last remaining members was Abel Salcedo, a Mexican Mormon who had a Jewish bakery in Lake Forest and joined in 1963.

Despite this fascinating history, “the contributions of the bakers and their cohorts of community activists have been overlooked by generations of historians,” Luce argues. Even Jewish historians of L.A. dismissed them as “under communist dominance” and “largely stripped the history of [Boyle Heights] of the radicalism and communism” that Local 453 helped to foster.

“The bakers and their supporters fought hard to protect the rights of immigrant workers and by doing so, they helped to foster an atmosphere of internationalism, anti-racism and working class solidarity in the neighborhood,” Luce told L.A. Taco. “No doubt they would stand with the folks fighting displacement and police brutality in Boyle Heights today.”

One group hasn't forgotten Local 453: Defend Boyle Heights, the group demonized by Fox News and others for protesting Asher Cafe. They gave the following statement to L.A. Taco:

DBH will fight against all forms of hate and oppression, especially when it comes from people who should understand our position. Reflecting on our neighborhood's ancestors, including the many socialist Jewish leaders that built community so fiercely, we acknowledge them as our comrades. We do not stand for anti-Semitism. We also will not stay silent when a Trump-loving bakery/coffee shop owner happens to be on the wrong side of Boyle Heights' Jewish, working class, baking, and immigrant history.

You hear that, Proud Boys? The ghosts of Boyle Heights' Jewish past looks down on schlemeils like y'all ...

RELATED: Self-Help Graphics Will Own Its Own Building for the First Time in Its History