[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]here are two-schools-in-one at the Baldwin Hills Elementary School site: a magnet called Baldwin Hills Elementary Pilot, hence the name, and New LA Elementary, a charter school that was placed there three years ago.

Baldwin Hills Elementary teachers are unionized and bargain collectively with UTLA, so its teachers this week are on strike. New LA, like the majority of other charter schools, does not have a union, so its teachers are working.

On the second morning of the strike, the Baldwin Hills Elementary Pilot teachers who were picketing on Rodeo Road decided to move their line to a shared campus driveway that is used as the entrance to New LA. They began walking in a circle at the driveway, which prevented vehicles from leaving the site and prevented New LA parents from entering to drop off their kids.

The New LA staff was forced to receive students on the sidewalk outside. And things got tense.

At one point, a vehicle trying to exit the driveway inched forward against the backs of the picketing teachers until the vehicle’s hood was nearly touching the circling picketers’ signs. They wouldn’t open a path.

“As long as we keep moving, it is legal to march on a sidewalk,” came a reminding call from Marie Germaine, the union chapter leader at Baldwin Hills Elementary.

The marching continued. Flustered, the driver rolled down a window and began shouting and complaining as he tried to leave the driveway. At one point, a man physically tried to push teachers out of the way. “Don’t touch me!” a Baldwin Hills teacher yelled back.

RELATED: The Strike Is On! Live Updates From the Picket Lines

Scenes like this are playing out across Los Angeles this week as L.A.’s public-school teachers go on a historic strike. But the tensions between public schools and charter schools have been simmering for years at campuses known as “co-location” sites. At these, privately run charter schools sit on public school property, and compete in local communities for enrollment — and per-pupil funding — as well as crucial instructional space.

'Special services for students don’t matter to the district.'

The effect in some cases is one of a blatant encroachment of physical space, as seen by the example of the Baldwin Hills campus. State law requires that districts allocate space to public charter school students, so districts are forced to shove nascent charter schools onto existing public school campuses, exacerbating tension and discomfort between students, educators, and parent communities.

There are 68 such sites in LAUSD today, a district spokesperson said.

New LA, for example, has taken over Baldwin Hills classrooms that were once used for the public school’s computer labs and art classes, in addition to spaces once used by specialists and therapists, said Baldwin Hills Principal Letitia Johnson-Davis, in an interview with LA Taco.

On Tuesday, after the brief shoving incident, two police officers arrived at the driveway. “We just want them to know what the rules are, and that they have to be safe,” one of the LAPD officers told me.

The officer walked into the picket line and tried to talk to anyone who might be in charge, but he was mostly ignored. Eventually, the police spoke to Germaine, the UTLA local leader. She said she reminded the police of the teachers’ rights to march, walk, and protest on a public sidewalk.

“We have a right to exercise our full rights to protest,” Germaine, an ardent leader to her fellow teachers, told me later.

“It’s an uncomfortable situation, but it’s been an uncomfortable situation every day that we’ve been here at this charter co-location,” she added. “They are co-located with a public school that is unionized. Obviously, these are the things that they’re going to have to deal with.”

[dropcap size=big]A[/dropcap]nd so on Wednesday afternoon, the striking teachers returned to the driveway. New LA students were being received for pick-up at the Baldwin Hills Recreation Center, next-door. Each time a car came by from the driveway, the picketing teachers would hold the line until the last possible moment, a tense dance between vehicle and people, every time.

It’s been a slog; the strike coincided with the heaviest seasonal rains so far this year. But the hours of marching around (7 to 9 in the morning, 2 to 4 in the afternoon, plus the general actions with the broader union) instead of being with their students is worth it for members like Java DeLaura, an LAUSD occupational therapist with 19 years of experience.

She works at Baldwin Hills Elementary and another school without a co-location charter. She has room to treat students there, but not here.

“I do not have a location to treat my students with special needs,” DeLaura said, with intent and exasperation. “I used to have a room. The charter school took that classroom. Now I work in a storage closet, a room stacked with boxes, a room with less than ten-square-feet, to provide services for students that need movement therapy.”

Baldwin Hills Elementary is a unique school in that its student body is 80 percent African-American or African, in a district that is largely Latino and has been for years. The school serves low-income students as well as students whose parents are from the other parts of black L.A., parents who seek out the school for its focus on ensuring their children will achieve.

“There are students at this school that require speech therapy, physical therapy, counseling, the charter school comes in, takes the room, and we’re told, 'Make it work',” DeLaura, the striking therapist, went on. “I don’t have a place to store my equipment to work with my students, so my car is full of equipment because I don’t have a place to keep it ... because special services for students don’t matter to the district.”

RELATED: A Struggle Against Charters: This Is Why Teachers in Los Angeles Are on Strike

Baldwin Hills Elementary opened its doors on July 1, 1943. Johnson-Davis, who holds a doctorate in education, arrived as principal in 2014.

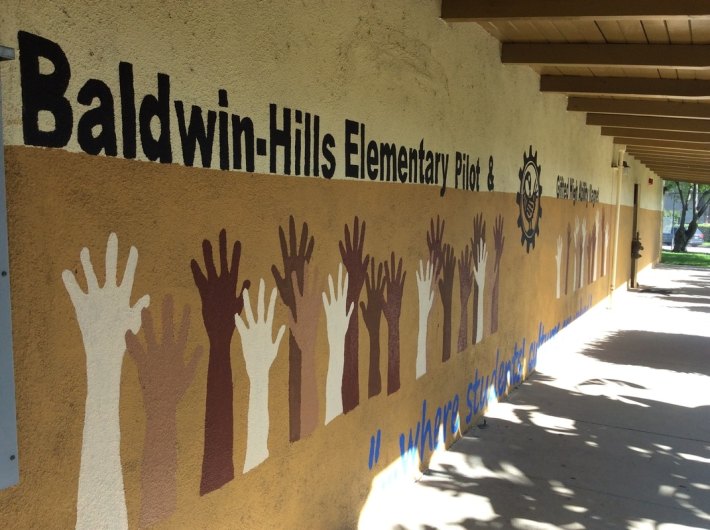

When parents tour her school, Johnson-Davis told me, some leave concluding it is “Wakanda” for its deep commitment to “African American excellence” and its historic role in the Baldwin Hills community. Bright, geometric West African-themed art motifs adorn the walls. Most of the teachers and staff are black. Johnson-Davis has already notched hires who’ve gone on to be named districtwide Rookie Teachers of the Year, she proudly noted.

Johnson-Davis sighs and flutters her eyes as she seeks to answer a question about what effect the co-location of New LA Elementary has had on her school.

“Even if I’ve got visual arts, a parent-run after-school program, a room for intervention, wonderful things happening, if there is not a teacher in that room with students on a roster, that room can be flipped for a charter school to occupy,” Dr. Johnson-Davis said.

When reached by L.A. Taco, New LA executive director Brooke Rios said she would not comment specifically on the claim over allocation of classroom space for her charter school at the Baldwin Hills Elementary site. She encouraged me to research Proposition 39, the 2000 voter-approved ballot initiative that resulted in rules requiring districts to hand over space to new charters.

“We were assigned open classroom space on campus,” Rios said in an interview.

But Johnson-Davis was plain about the effects the co-location structure has had on her school. “The co-location charter … has been a drain on resources, space, and we’ve been vocal in advocating and fighting against [it],” she said. “Our parent community submitted a 10,000-signature petition to the district this spring over the continued encroachment of our space by the co-located charter.”

“If a classroom doesn’t have a roster-carrying teacher in it, meaning they aren’t [recuperating] any attendance dollars from that room, it’s vulnerable,” Johnson-Davis said.

[dropcap size=big]L[/dropcap]eaders are at a logjam. In an open letter last week sent to Alex Caputo-Pearl, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, the CEO of the California Charter School Association said she and UTLA are on the same team: the best education for students.

“This ‘us versus them’ mentality is disappointing, and I fear, dangerous,” wrote Myrna Castrejón. “I ask you to ensure that words, demonstrations, and actions are peaceful, civil, and set a good example for the kids we all care so much about.”

The notion of what ‘setting a good example’ is has also become murky as teachers enter their fourth day of picketing outside hundreds of school sites across Los Angeles. The district and the union are set to meet again on Thursday afternoon.

For Johnson-Davis, the Baldwin Hills Elementary School principal, the run-up to the strike was challenging and emotional for her school community. But she said she understands the motives.

“The district gives us a nurse one day. We make budgetary decisions to try to have extra services, we decide, ‘Are we going to have another day of a nurse? Another day of a psychologist? Another day with a counselor?' We have to figure these things out, because they don’t exist.”

All the district told her was “to have a plan” in case the strike happened. On Monday, it did. Her 22 teachers are on the line. She told me 75 percent of her students are absent. “And if I’m candid, I’m also a parent here,” the principal added. “My children are not here either.”