Think of Los Angeles like a birthday cake.

When you’re cutting up a cake, you’re gonna try to cut the pieces up pretty equally. Now imagine that the cake is covered in sprinkles. And the sprinkles are unevenly distributed, kind of like people in a city. But you want every piece of cake to have about the same number of sprinkles, kind of like a council district.

Cutting the cake is like redistricting.

Once every decade, we redraw the borders of Los Angeles’s districts… ostensibly, to keep about the same number of people in each district. About 260,000.

In many ways, redistricting is about power—who’s got it, and who doesn’t. Anne Freiermuth, an activist with Ground Game LA, is following redistricting this year for the first time and said the process isn’t what she expected.

“It was just like layer after layer of naïveté and big-heartedness where I was like, this city—we’re so progressive. And just finding out how completely unprogressive we are,” Freiermuth said.

The process is supposed to be apolitical. But often, it isn’t.

“It's the division of power in its most raw political form,” said Rob Quan, an activist who lives in Highland Park and runs Unrig LA, a city hall watchdog group.

He said it’s way more complicated than splitting up the districts and deciding which council member gets what area. There’s a lot to consider. “You can build power for people that don't have representation right now, or you can undermine all of that,” Quan said.

“We have wildly different populations that are eligible to vote in districts—wealthier, whiter districts … compared to other districts that are made up with larger immigrant communities.”

Redistricting “can unite communities,” he said.

Here’s how redistricting actually works. The first maps are drawn by a 21-member commission appointed by city council members and other city officials. The commissioners are supposed to act independently from the politicians who appointed them. Over the course of several months, commissioners hold meetings where the public can comment on drafts of the map. Eventually, a map is sent to the city council for final approval.

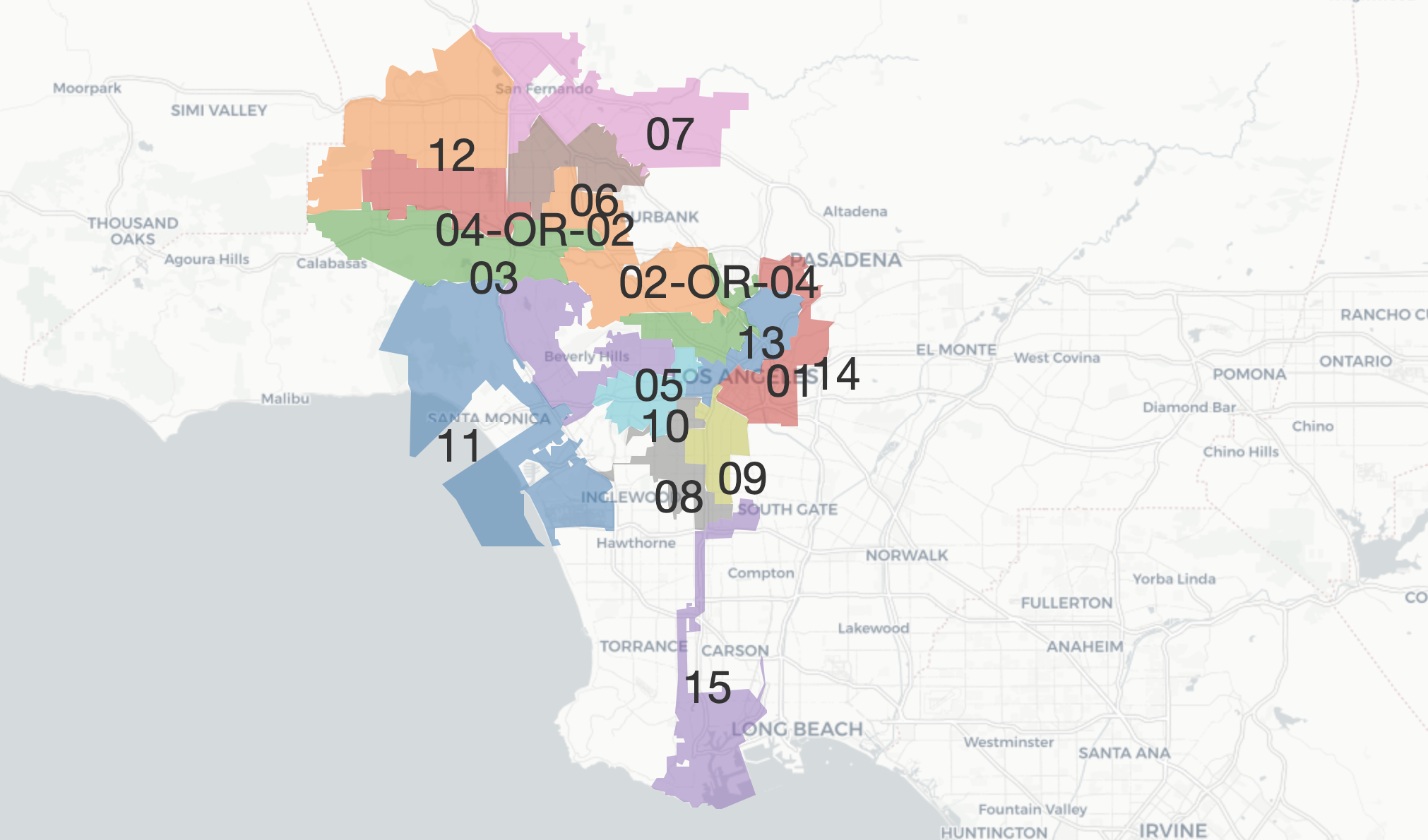

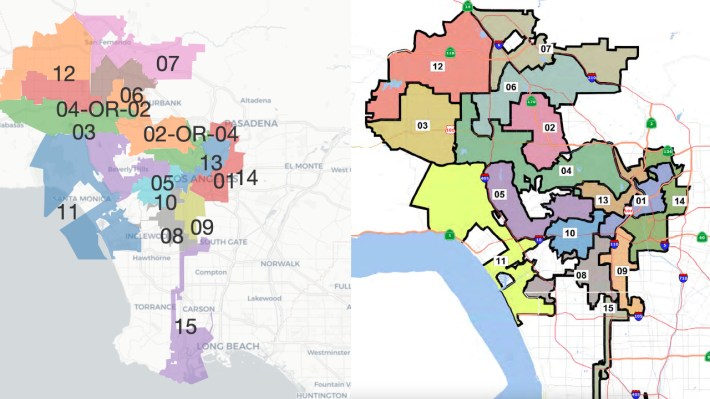

In early October, the commission released a map – map K2.5. It proposed massive changes to two districts—council district (CD) 4 and CD 2 – potentially reassigning them to almost entirely new constituencies. Paul Krekorian of CD 2 called the map “outrageous.” (Here’s the current council district map of L.A. for comparison.)

Councilmember Nithya Raman, who represents CD 4, tweeted a picture of map K2.5 where she drew a red circle around the newly proposed districts and wrote “What?! Commissioner Sonja Diaz from CD 14, said in an interview with L.A. TACO that the proposed changes to CD 4 were warranted.

“Look at the 2011 map. It’s gerrymandered,” said Diaz. “Look at city council district four, look at the lack of political voice and opportunity of Asian Americans and Latinos for the fastest growing populations.”

Diaz said the goal of map K2.5 was to keep communities together. “So I don’t think that anybody lost out in this process.”

The existing boundaries of CD 4 have it stretching across Griffith Park and the San Fernando Valley, and down into Hollywood and Koreatown. In map K2.5, a proposed district labeled “CD 4-or-2” is one concentrated area in the southern part of the San Fernando Valley.

In an interview with L.A. TACO following the release of map K2.5, Raman said she knew that CD 4 had a “strange shape” that might have to change. “But the enormity of the changes proposed are what strikes me as highly unexpected,” she said.

Raman, who is the newest member of the city council and also known for being the most progressive, would have to make her case to an almost entirely new constituency.

Raman pointed out that if she were assigned a new area to govern, she would suddenly represent a new constituency with different needs and values.

It could also make it difficult to impossible for her to get re-elected. Raman, who is the newest member of the city council and also known for being the most progressive, would have to make her case to an almost entirely new constituency. And most of the people who voted for her platform advocating for more affordable housing and living wages would be assigned a different representative.

Map K2.5 did have some fans—like homeowners in the San Fernando Valley. In a letter, the Sherman Oaks Homeowners Association applauded how the map consolidated the voting power of the Valley, which is on average more conservative than the rest of the city. “The map gives the Valley the fair share of districts that it has so long deserved,” the association wrote.

But Raman argued that the process itself is skewed. “People who have more resources to participate are empowered to participate,” she said.

Since the new district boundaries are supposed to be drawn according to what’s discussed in the public meetings, anyone with the time and resources to contribute is able to have an outsized influence on the end result.

Not to mention that you’ve got to have the time to understand the notoriously opaque and confusing process of redistricting. If you’ve got a second job, or are struggling to make ends meet, you may not have hours to get up to speed on redistricting.

“That's asking a lot from residents who are still reeling from the pandemic,” Raman said.

Following the uproar over map K2.5, the commission submitted it along with their final lengthy report to the city council. In it, they suggested the city add more council districts, creating more positions on the city council and creating a wider distribution of power among its representatives. The commission also requested the redistricting process be controlled by a body entirely independent from the city council.

In response to the report, city council members filed dozens of motions to amend the map, then formed an ad hoc redistricting committee to suggest their own district lines.

That seven-member committee was appointed by city council president Nury Martinez and included her, Kevin De León, Nithya Raman, and Mitch O’Farrell. They released their own map in the first week of November, voted through by everyone except Raman, the sole dissenter. That map is a hybrid of K2.5 and another map from a Latino labor organization.

The committee’s hybrid map has Raman representing a sprawling area, but just 40 percent of her existing district. She would take on parts of Studio City and Sherman Oaks, and lose Miracle Mile and the Hollywood flats.

After the hybrid map was released, Raman said in a statement that she was “overjoyed to meet my new constituents,” but also expressed dissatisfaction with the redistricting process, saying it “unnecessarily left so many Angelenos in the dark.”

“This outcome was not inevitable, and it is only because of the advocacy of our constituents that we were able to retain as much of [the district] as we did,” she wrote.

You may be wondering why both maps—K2.5 and the hybrid—involve such drastic changes to CD 4. So are a lot of people.

Activists and political watchdogs have suggested that the changes are a reaction to Raman’s progressive platform. Quan said it could be the commission’s way of slowing her momentum.

“They look at a young woman of color, steamrolling through and dislodging an incumbent official, along with a progressive message of challenging and heaving the establishment,” Quan said.

“So I think this is just a way of sandbagging her to an extent.”

When we asked Raman why she thought such drastic changes had been proposed in map K2.5, she didn’t answer right away. “That's a good question,” she said. “Can I get back to you on that?”

We emailed Raman’s staffers to follow up, and they redirected us to the commissioner appointed by CD 4, Jackie Goldberg.

In the last redistricting, in 2012, the map was redrawn to move downtown into CD 14, then the district of former council member Jose Huizar. He was later indicted for allegedly soliciting bribes from luxury developers looking to build in downtown L.A. Nearly all the crimes Huizar is accused of committing would’ve been impossible if downtown hadn’t been redrawn into CD 14.

Goldberg said that throughout the redistricting process, she witnessed some of her colleagues working with a clear focus on redrawing two districts: CD 3, in the west San Fernando Valley, and CD 5, which borders CD 3 in the Valley and stretches into West L.A. Goldberg said she'd never seen anything like it.

“Their goal, it appeared to me—nobody said what their goal was, I'm just telling you my impression—that there were only two council districts they cared about, [CD] 5 and [CD] 3,” Goldberg said.

The commissioner said she couldn’t be sure if CD 4 was just collateral damage, or if there was a targeted campaign against Raman.

“Could they have said, ‘The best thing for us to do is go after Nithya, she's new, she’s a pain in the butt, we'll go after her’? Yes. It’s also a possibility that they didn't care who it was they affected, once they took care of their primary goal,” Goldberg said.

“I don't know and I don't really care. The effect was the same whether it was intentional or not.”

So it’s not clear why the commission and city council committee suggested such radical changes for CD 4. But it’s not the first time redistricting has prompted outrage.

In the last redistricting, in 2012, the map was redrawn to move downtown into CD 14, then the district of former council member Jose Huizar. He was later indicted for allegedly soliciting bribes from luxury developers looking to build in downtown L.A. Nearly all the crimes Huizar is accused of committing would’ve been impossible if downtown hadn’t been redrawn into CD 14.

That time around, two council members were stripped of large portions of their districts: Jan Perry lost downtown L.A. from CD 9, and Bernard Parks lost a big part of what was formerly CD 8. The executive director of that redistricting commission was a former staffer of former city council president Herb Wesson. (This time around, council members Curren Price of CD 9 and Marqueece Harris-Dawson of CD 8 played political tug-of-war over Exposition Park and USC. The new hybrid map has placed them in Price’s district).

In a Los Angeles Times op-ed published last year, Parks and Perry said “the way it was done in 2012 was, as this newspaper put it, ‘the result of backroom deals,’ that were ‘used to punish enemies and reward friends and supporters’ of then-Council president Herb Wesson and his allies … Wesson was ultimately able to get the lines drawn the way he wanted them.”

This year’s redistricting is “very different from last time,” Raman said.

She was referencing, in part, a number of rule changes made since the last redistricting, aimed at increasing the transparency and independence of the redistricting commission. But despite the changes, this year’s redistricting has often felt inscrutable to the watchdogs and residents trying to understand what’s going on.

When we asked Quan what he thought about the committee’s map and the changes to CD 4, he said “I don't know, I really don't have a take on that.”

“In some ways, it's better … In a lot of ways it's a preservation of the status quo with some tweaks,” he said.

“I mean, there's only so much you can expect through this bullshit process” without fundamentally changing how the city of Los Angeles does redistricting, Quan said.

The seven-member city council committee’s proposed plan has one more public hearing on November 23. After, the council will vote on a more finalized version of the map on December 1.

This article was published in collaboration with Neon Hum. If you are interested to see how redistricting led to Jose Huizar's corruption charges, check out episode 5 of 'The Sellout.'